Than Words 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Guess What Or Who…

Over to You 2001/2002 Guess What or Who 2 – Countries Programmanus 01058/ra15 GUESS WHAT OR WHO… PART 2 – COUNTRIES Manus: Amy Bruford Producent: Claes Nordenskiöld Sändningsdatum: 15/1, 2002 Längd: 9'26 Music: "Guess What or Who… Theme Song – Introduction" (Red Hot Chili Peppers "I Like Dirt" and Public Enemy "Fight the Power") Leigh: Welcome to the second programme in our new series GUESS WHAT OR WHO … This time our theme is – COUNTRIES. You'll hear one person from our panel speak about a specific country, your job is to figure out which. Our panel consists of Solange… Solange: Hi. Leigh: …Sam… Sam: Hello. Leigh: …and Kaitlin. Kaitlin: Hi. Leigh: If you have the worksheet in front of you, you have four alternatives to choose from. If you don't, just write down your answer on a piece of paper. We'll give you the correct answers at the end of the programme. We'll describe eight different countries, so let's get started. Here's the first. Which country does SOLANGE describe? Solange: My mother actually comes from this country where they speak both English and Swahili. It's less than half the size of Sweden, but more than twice as many people live there. The capital is called Kampala, which is right on a large lake, Lake Victoria. The colours of the flag are black, red and yellow. Leigh: Which country was that: Uganda, Sudan, Zimbabwe or Nigeria? Write your answer next to number 1. 1 Over to You 2001/2002 Guess What or Who 2 – Countries Programmanus 01058/ra15 Music: Ikoce "Kec" Leigh: Now to the second question and our second country. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

On Music Angels God Only Knows

On Music Angels God Only Knows David Milo Kirkham Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday The trek from my office at the Air Force Academy history department to the faculty parking lot was long enough—about a ten-minute walk—suf- ficient time for some substantive thinking. One winter evening in about 1992, as I made the walk, my Comparative Revolutions course weighed on my mind. As I pondered how I might introduce the next day’s discus- sion on causes of revolutions, I climbed into my 1987 red Dodge Colt more out of habit than deliberation. At the turn of the ignition key, the radio’s boom broke my reverie and jarred me back to the reality of my immediate surroundings. “Where did it go, that yester-glow, . yester-me, yester-you,” rang out the soulful tenor voice of Stevie Wonder from Colorado Springs’ sole oldies station. A decent song, I thought, ready for a musical interlude to my heavy thinking, but I wonder what’s on the other stations. My fingers instinctively hit the button for the only other accessible old- ies station, from Pueblo, Colorado, fifty-seven miles to the south. Recep- tion of Pueblo’s station wasn’t always very good at my house in the Springs, but sometimes I could pick it up while perched on the mountainside where the Academy was located. That night, in fact, I was in luck. The music came in softly but clearly: “Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday.” Stevie Wonder. That’s odd, I thought. The same more-than-twenty-year-old song play- ing at the same time on two different stations in two different towns. -

Top Wedding Song Choices

Top Wedding Song Choices A Groovy Kind of Love Phil Collins A Moment Like This Kelly Clarkson A While New World Peabo Bryson/Regina Belle After All Peter Cetera All About Lovin’ You Bon Jovi All My Life K-CI and JO JO All the Way Frank Sinatra Always Atlantic Starr Always Bon Jovi Amazed Lonestar Angel in My Eyes John Michael Montgomery Angel of Mine Monica At Last Etta James Beautiful in my Eyes Joshua Kadison Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Best Part of Me Joe Wodarek Breathe Faith Hill By Your Side Sade Can You Feel The Love Elton John Can’t Help Falling In Love Elvis Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You Frankie Valli Color My World Chicago Come What May McGregor/Kidman Could I Have This Dance Anne Murray Crazy for You Madonna Don’t Know Much Linda Rondstadt/Aaron Neville Dreaming of You Selena Endless Love Diana Ross/Lionel Ritchie Everything I Do Bryan Adams Everytime I Close My Eyes Babyface Faithfully Journey Feels Like Home Chantal Kreviazuk First Time Ever I Saw Your Face Roberta Flack Fly Me to the Moon Frank Sinatra Flying Without Wings Ruben Studdard For the First Time Kenny Loggins For You Kenny Lattimore For You I Will Monica Forever Beach Boys Forever and Ever Randy Travis Forever and Always Shania Twain Forever In Love Kenny G Forever More James Ingram Forever My Lady Jodeci Forever’s as Far as I’ll Go Alabama From Here to Eternity Michael Patterson From Now On Regina Belle From This Moment Shania Twain Give Me Forever John Tesh/James Ingram Giving You the Rest of My Life Bob Carlisle Glory of Love Peter Cetera God Must Have -

Dades Personals

Instituto Interuniversitario de Desarrollo Social y Paz DOCTORADO EN ESTUDIOS INTERNACIONALES DE PAZ, CONFLICTOS Y DESAROLLO Tesis Doctoral Dancing Conflicts, Unfolding Peaces: Dance as Method to Elicit Conflict Transformation Presentada por: Paula Ditzel Facci Dirigida por: Dr. Norbert Koppensteiner Castellón de la Plana, Mayo 2017 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................... 1 Extracto de la Tesis Doctoral en Castellano ............................................................................... 2 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 16 1 Objective and Motivation ...................................................................................................... 19 1.1 Author’s Perspective ....................................................................................................... 19 1.2 Research Interest ............................................................................................................. 24 1.3 Method and Structure ...................................................................................................... 28 1.3.1 Literature Review .................................................................................................... -

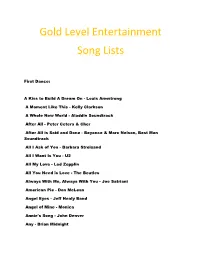

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 6/26/2020 7PM through 6/26/2020 11P s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 07:00:00p 00:00 Friday, June 26, 2020 7PM 07:00:00p 04:18 JUSTIFIED & ANCIENT (NO RAP EDIT) / THE KLF (FEATURING TAMMY WYNETTE) 07:04:18p 03:35 GRENADE / BRUNO MARS 07:07:53p 03:43 WHERE HAVE ALL THE COWBOYS GONE? / PAULA COLE 07:11:42p 03:26 TAKE ME HOME TONIGHT/BE MY BABY / EDDIE MONEY 07:15:08p 03:15 CRUSH / JENNIFER PAIGE 07:18:29p 03:18 TIK TOK / KE$HA 07:21:47p 04:07 MORE THAN WORDS / EXTREME 07:26:00p 03:35 TARZAN BOY / BALTIMORA 07:29:40p 03:30 STOP-SET 07:36:27p 04:05 THINGS THAT MAKE YOU GO HMMMM... / C & C MUSIC FACTORY 07:40:32p 02:46 I'M A BELIEVER (RADIO EDIT) / SMASH MOUTH 07:43:18p 03:47 THE LOOK / ROXETTE 07:47:11p 03:09 ALL I WANT / TOAD THE WET SPROCKET 07:50:20p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:00:00p 00:00 Friday, June 26, 2020 8PM 08:00:00p 03:43 FOOTLOOSE / KENNY LOGGINS 08:03:43p 04:03 SIMPLY IRRESISTIBLE / ROBERT PALMER 08:07:46p 03:40 KISS ON MY LIST / HALL & OATES 08:11:26p 03:58 MONEY FOR NOTHING / DIRE STRAITS 08:15:24p 04:08 TAINTED LOVE / WHERE DID OUR LOVE GO / SOFT CELL 08:19:32p 04:41 CAN'T FIGHT THIS FEELING / REO SPEEDWAGON 08:24:13p 02:56 I'M STILL STANDING / ELTON JOHN 08:27:13p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:33:57p 03:59 ALL I NEED IS A MIRACLE / MIKE + THE MECHANICS 08:37:56p 03:57 LET'S DANCE / DAVID BOWIE 08:41:53p 04:03 EVERYBODY HAVE FUN TONIGHT (RADIO EDIT) / WANG CHUNG 08:45:56p 03:41 HERE COMES THE RAIN AGAIN / EURHYTHMICS 08:49:37p 03:05 UPTOWN GIRL / BILLY JOEL 08:52:42p 03:30 STOP-SET 09:00:00p 00:00 Friday, -

King Lear PRE-AP*/AP*

Applied Practice in King Lear PRE-AP*/AP* By William Shakespeare RESOURCE GUIDE *AP is a registered trademark of the College Entrance Examination Board, which was not involved in the production of, and does not endorse, this product. Pre-AP is a trademark owned by the College Entrance Examination Board. ©2017 by Applied Practice, Dallas, TX. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2017 by Applied Practice All rights reserved. No part of the Answer Key and Explanation portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Only the Student Practices portion of this publication may be reproduced in quantities limited to the size of an individual teacher’s classroom. It is not permissible for multiple teachers to share a single Resource Guide. Printed in the United States of America. Directions: This part consists of selections from King Lear and questions on their content, form, and style. After reading each passage, choose the best answer to each question. Note: Pay particular attention to the requirement of questions that contain the words NOT, LEAST, or EXCEPT. Passage 1, Questions 1-8. Read the following passage from Act I, scene i of King Lear carefully before you choose your answers. Enter one bearing a coronet, then King Lear, Cornwall, Albany, Goneril, Regan, Cordelia, and Attendants. Lear. Attend the lords of France and Burgundy, Gloucester. Glou. I shall, my lord. [Exit with Edmund]. Lear. Mean time we shall express our darker purpose. -

Download Song List

PURPLE RAIN PRINCE BLISTER IN THE SUN VIOLENT FEMMES 3AM MATCHBOX 20 BLUE SUEDE SHOES CARL PERKINS 500 MILES THE PROCLAIMERS BLUEBERRY HILL FATS DOMINO CECILIA SIMON & GARFUNKEL BOOT SCOOTIN’ BOOGIE BROOKS & DUNN 867-5309 (JENNY) TOMMY TUTONE BORN TO BE WILD STEPPENWOLF IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS BORN TO RUN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN YOU CAN’T HURRY LOVE PHIL COLLINS BRANDY LOOKING GLASS AFRICA TOTO BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S DEEP BLUE SOMETHING ROSANNA TOTO BRICK HOUSE THE COMMODORES AIN’T TOO PROUD TO BEG THE TEMPTATIONS BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATERS SIMON & MY GIRL THE TEMPTATIONS GARFUNKEL ALL ABOUT THE BASS MEGHAN TRAINOR BROWN EYED GIRL VAN MORRISON ALL APOLOGIES NIRVANA BUILD ME UP BUTTERCUP THE FOUNDATIONS ALL FOR YOU SISTER HAZEL BYE BYE LOVE THE EVERLY BROTHERS ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’ THE MAMAS & THE PAPAS ALL OF ME JOHN LEGEND CANDLE IN THE WIND ELTON JOHN ALL SHOOK UP ELVIS PRESLEY CAN’T BUY ME LOVE THE BEATLES ALL SUMMER LONG KID ROCK CAN’T FIGHT THIS FEELING REO SPEEDWAGON ALLENTOWN BILLY JOEL CAN’T GET ENOUGH BAD COMPANY ALREADY GONE EAGLES CAN’T SMILE WITHOUT YOU BARRY MANILOW ALWAYS SOMETHING THERE TO REMIND ME CAN’T TAKE MY EYES OFF OF YOU FRANKIE VALLI NAKED EYES CAN’T YOU SEE MARSHALL TUCKER BAND AMERICA NEIL DIAMOND CAPTAIN JACK BILLY JOEL AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN CECILIA SIMON & GARFUNKEL AMIE PURE PRAIRIE LEAGUE CELEBRATION KOOL & THE GANG ANGEL EYES JEFF HEALEY BAND CENTERFIELD JOHN FOGERTY ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PINK FLOYD CENTERFOLD J. GILES BAND ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE CHAMPAGNE -

Bruno Mars 2. Accidently in Love – Counting Crows 3

1.Marry You – Bruno Mars 2. Accidently In Love – Counting Crows 3. Brighter Than Sunshine – Aqualung 4. For Once In My Life – Stevie Wonder 5. Nothing Else Matters – Metallica 6. Everything – Michael Bublé 7. Love On Top – Beyonce 8. You Got the Love – Candi Staton 9. Fly Me To The Moon – Frank Sinatra 10. 1, 2, 3, 4 – Feist 11. At Last – Etta James 12. Dream a Little Dream of Me – The Mamas & The Papas 13. Candy – Paolo Nutini 14. Greatest Day – Take That 15. It Must Be Love – Madness 16. (I Can’t Help) Falling In Love With You – UB40 17. It Had To Be You – Harry Connick Jr 18. Cupid – Sam Cooke 19. One Day Like This – Elbow 20. Close to Me – The Cure 21. How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You) – James Taylor 22. More Than Words – Extreme 23. Baby, Now That I’ve Found You – Alison Krauss 24. Feeling Good – Muse 25. She – Elvis Costello 26. If There Is Something – Roxy Music 27. Just Say Yes – Snow Patrol 28. Stand By Me – Ben E King 29. The Way You Look Tonight – Frank Sinatra 30. I Only Have Eyes For You – Billie Holiday 31. Truly Madly Deeply – Savage Garden 32. At My Most Beautiful – REM 33. Unforgettable – Nat King Cole 34. Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol 35. What A Wonderful World – Louis Armstrong 36. Gotta Get You Into My Life - The Beatles 37. Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen 38. Wonderwall – Oasis 39. Yellow – Coldplay 40. You're Beautiful – James Blunt 41. You're The First, The Last, My Everything – Barry White 42. -

A Taste of Honey

A Taste Of Honey - Boogie Oogie Oogie.zip A-ha - Analogue.zip Abba - Dancing Queen.zip Abba - Waterloo.zip ABBA-DANCING QUEEN.zip Adam Sandler - Ode To My Car.zip Adele Rumour Has It.mp4 Adele Cold Shoulder.mp4 Adele Don't You Remember.mp4 Adele Promise This.mp4 Adele I miss you.mp4 Adele - 'Turning Table' Karaoke.mp4 Adele - All I ask.mp4 Adele - Don't You Remember.mp4 Adele - I'll Be Waiting.mpg Adele - Love in the dark.mp4 Adele - Million years ago.mp4 Adele - One And Only.mp4 Adele - Remedy.mp4 Adele - River Lea.mp4 Adele - Rolling In The Deep.mp4 Adele - Send My Love (To Your New Lover).mp4 Adele - Set Fire To The Rain.mp4 Adele - Skyfall - (2013) (Orijinal Stüdyo).mpg Adele - Skyfall.mp4 Adele - Someone Like You.mp4 Adele - Sweetest Devotion.mp4 Adele - Water Under The Bridge.mp4 Adele - When we were young.mp4 Adele Best For Last.mp4 Adele Black And Gold.mp4 Adele Can't let go.mp4 Adele Chansing Pavements.mp4 Adele Crazy For You.mp4 Adele Daydreamer.mp4 Adele He Won't Go.mp4 Adele Hello.mp4 Adele I found a boy.mp4 Adele Love Song.mp4 Adele Make You Feel My Love.mp4 Adele Melt My Heart To Stone.mp4 Adele take it all.mp4 Adele That's It, I Quit, I'm Movin' On.mp4 aero smith Walk_This_Way.mid Aerosmith - Jaded.zip Aerosmith - Janie's Got A Gun.zip Aerosmith - Livin' On The Edge.zip Aerosmith - Love In An Elevator.zip Aerosmith - Rag Doll.zip Aerosmith - Same Old Song And Dance.zip Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion.zip Aerosmith - The Other Side.zip Aerosmith - Walk This Way.zip Aerosmith - What It Takes.zip Aerosmith Angel.zip Aerosmith Back