The Fate of Folklore and Folk Song Collections in the Isle of Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

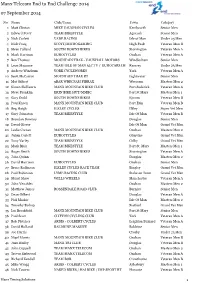

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014 No Name Club/Team Town Category 1 Matt Clinton MIKE VAUGHAN CYCLES Kenilworth Senior Men 2 Edward Perry TEAM BIKESTYLE Agneash Senior Men 3 Nick Corlett VADE RACING Isle of Man Under 23 Men 4 Nick Craig SCOTT/MICROGAMING High Peak Veteran Men B 5 Steve Calland SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 6 Mark Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Veteran Men A 7 Ben Thomas MOUNTAIN TRAX - VAUXHALL MOTORS Windlesham Senior Men 8 Leon Mazzone TEAMCYCLING ISLE TEAM OF MAN 3LC.TV / EUROCARS.IM Ramsey Under 23 Men 9 Andrew Windrum YORK CYCLEWORKS York Veteran Men A 10 Scott McCarron MOUNTAIN TRAX RT Lightwater Senior Men 11 Mat Gilbert 9BAR WRECSAM FIBRAX Wrecsam Masters Men 2 12 Simon Skillicorn MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Soderick Veteran Men A 13 Steve Franklin ERIN BIKE HUT/MMBC Port St Mary Masters Men 1 14 Gary Dodd SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Epsom Veteran Men B 15 Paul Kneen MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Erin Veteran Men B 16 Reg Haigh ILKLEY CYCLES Ilkley Super Vet Men 17 Gary Johnston TEAM BIKESTYLE Isle Of Man Veteran Men B 18 Brendan Downey Douglas Senior Men 19 David Glover Isle Of Man Grand Vet Men 20 Leslie Corran MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Onchan Masters Men 2 21 Julian Corlett EUROCYCLES Glenvine Grand Vet Men 22 Tony Varley TEAM BIKESTYLE Colby Grand Vet Men 23 Mark Blair TEAM BIKESTYLE Port St. Mary Masters Men 1 24 Roger Smith SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 25 John Quinn Douglas Masters Men 2 26 David Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Senior Men 27 Bruce Rollinson ILKLEY CYCLES RACE -

Isle of Man Government Tender Activity 2020/2021

Isle of Man Government Tender Activity 2020/2021 The Isle of Man Government Procurement Policy Procurement team updates added requires that Departments, Statutory Boards, Offices and other entities publish all contract No changes for: opportunities with an anticipated value in excess Comms of the tender threshold of £100,000. OFT PSPA Status Key: VWS Not Started – Department HAS NOT instructed Procurement Services that they are ready to proceed with the procurement. Planning – Procurement Services have received instruction from the Department. Procurement strategy and project plan are still to be agreed and/or the specification is being developed and the tender documents are being prepared. RFI – the Department is running a Request for Information to better understand the market prior to proceeding. EOI (Expressions of Interest) – the project is currently being advertised. PQQ (Pre-Qualification Questionnaire) – the project is subject to a short listing exercise (in advance of ITT being issued). ITT (Invitation to Tender) – the tender documents have been issued and are being completed by the bidders or have been returned. Mini Competition – Approved suppliers on the Framework have been invited to submit responses against one or more Lots AFA – Application for Admission has been published Evaluation – The bids are in the process of being evaluated. Exemption – The Department has requested/obtained Exemption from Financial Regulations. Contract – The winning bid has been selected, bidders have been notified. Agreement is being prepared for or awaiting signature. Completed – Agreements have been signed by all parties. On Hold – Project has been suspended by the Department. Cancelled – the Department has cancelled the project. Priority – the Department’s prioritisation of a project i.e. -

The 'Isle of Vice'? Youth, Class and the Post-War Holiday on the Isle of Man

The 'Isle of Vice'? Youth, class and the post-war holiday on the Isle of Man Hodson, P. (2018). The 'Isle of Vice'? Youth, class and the post-war holiday on the Isle of Man. cultural and social history. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780038.2018.1492789 Published in: cultural and social history Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 the author. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Cultural and Social History The Journal of the Social History Society ISSN: 1478-0038 (Print) 1478-0046 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfcs20 The ‘Isle of Vice’? Youth, class and the post-war holiday on the Isle of Man Pete Hodson To cite this article: Pete Hodson (2018): The ‘Isle of Vice’? Youth, class and the post-war holiday on the Isle of Man, Cultural and Social History To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14780038.2018.1492789 © 2018 The Author(s). -

Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960

‘…while the others did some capers’: the Manx Traditional Dance revival 1929 to 1960 By kind permission of Manx National Heritage Cinzia Curtis 2006 This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts in Manx Studies, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool. September 2006. The following would not have been possible without the help and support of all of the staff at the Centre for Manx Studies. Special thanks must be extended to the staff at the Manx National Library and Archive for their patience and help with accessing the relevant resources and particularly for permission to use many of the images included in this dissertation. Thanks also go to Claire Corkill, Sue Jaques and David Collister for tolerating my constant verbalised thought processes! ‘…while the others did some capers’: The Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960 Preliminary Information 0.1 List of Abbreviations 0.2 A Note on referencing 0.3 Names of dances 0.4 List of Illustrations Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Dancing on the Isle of Man in the 19th Century 5 Chapter 2: The Collection 2.1 Mona Douglas 11 2.2 Philip Leighton Stowell 15 2.3 The Collection of Manx Dances 17 Chapter 3: The Demonstration 3.1 1929 EFDS Vacation School 26 3.2 Five Manx Folk Dances 29 3.3 Consolidating the Canon 34 Chapter 4: The Development 4.1 Douglas and Stowell 37 4.2 Seven Manx Folk Dances 41 4.3 The Manx Folk Dance Society 42 Chapter 5: The Final Figure 5.1 The Manx Revival of the 1970s 50 5.2 Manx Dance Today 56 5.3 Conclusions -

Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. an Examination of Manx Farming Between 1750 and 1900

115 Manx Farming Communities and Traditions. An examination of Manx farming between 1750 and 1900 CJ Page Introduction Set in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man was far from being an isolated community. Being over 33 miles long by 13 miles wide, with a central mountainous land mass, meant that most of the cultivated area was not that far from the shore and the influence of the sea. Until recent years the Irish Sea was an extremely busy stretch of water, and the island greatly benefited from the trade passing through it. Manxmen had long been involved with the sea and were found around the world as members of the British merchant fleet and also in the British navy. Such people as Fletcher Christian from HMAV Bounty, (even its captain, Lieutenant Bligh was married in Onchan, near Douglas), and also John Quilliam who was First Lieutenant on Nelson's Victory during the Battle of Trafalgar, are some of the more notable examples. However, it was fishing that employed many Manxmen, and most of these fishermen were also farmers, dividing their time between the two occupations (Kinvig 1975, 144). Fishing generally proved very lucrative, especially when it was combined with the other aspect of the sea - smuggling. Smuggling involved both the larger merchant ships and also the smaller fishing vessels, including the inshore craft. Such was the extent of this activity that by the mid- I 8th century it was costing the British and Irish Governments £350,000 in lost revenue, plus a further loss to the Irish administration of £200,000 (Moore 1900, 438). -

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

William Cashen's Manx Folk-Lore

WI LLI AM CAS HEN WILLIAM CASHEN’S MANX FOLK-LORE william cashen 1 william cashen’s manx folk-lore 2 WILLIAM CASHEN’S MANX FOLK-LORE 1 BY WILLIAM CASHEN 2 Edited by Stephen Miller Chiollagh Books 2005 This electronic edition first published in 2005 by Chiollagh Books 26 Central Drive Onchan Isle of Man British Isles IM3 1EU Contact by email only: [email protected] Originally published in 1912 © 2005 Chiollagh Books All Rights Reserved isbn 1-898613-19-2 CONTENTS 1 Introduction i * “THAT GRAND OLD SALT BILL CASHEN” 1. Cashin: A Character Sketch (1896) 1 2. William Cashin: Died June 3rd 1912 (1912) 2 3. The Old Custodian: An Appreciation (1912) 9 * “loyalty to Peel” 4. “Madgeyn y Gliass” (“Madges of the South”) 13 5. Letter from Sophia Morrison to S.K. Broadbent (1912) 15 6. Wm. Cashen’s Manx Folk Lore (1913) 16 * CUSTOMS AND SUPERSTITIONS OF THE MANX FISHERMEN 7. Superstitions of the Manx Fishermen (1895) 21 8. Customs of the Manx Fishermen (1896) 24 * CONTENTS * william cashen’s manx folk-lore Preface 31 Introduction (by Sophia Morrison) 33 ɪ. Home Life of the Manx 39 ɪɪ. Fairies, Bugganes, Giants and Ghosts 45 ɪɪɪ. Fishing 49 ɪv. History and Legends 59 v. Songs, Sayings, and Riddles 61 1 INTRODUCTION In Easter 1913, J.R. Moore, who had emigrated from Lonan to New Zealand,1 wrote to William Cubbon: I get an occasional letter from my dear Friend Miss Morrison of Peel from whom I have received Mr J.J. Kneens Direct Method, Mr Faraghers Aesops Fables, Dr Clague’s Reminiscences in which I[’]m greatly disappointed. -

Rule of Law : the Backbone of Economic Growth

Rule of law : the backbone of economic growth (A lecture delivered by Deemster David Doyle at the Oxford Union on 17 July 2014 as part of the Small Countries Financial Management Programme) Introduction “By this Book and the Holy Contents thereof and by the wonderful Works that GOD hath miraculously wrought in Heaven above and in the Earth beneath in Six Days and Seven Nights; I David Charles Doyle do swear that I will without respect of favour or friendship, love or gain, consanguinity or affinity, envy or malice, execute the Laws of this Isle justly betwixt Our Sovereign LADY THE QUEEN and Her Subjects within this Isle, and betwixt Party and Party as indifferently as the Herring Backbone doth lie in the midst of the Fish. So help me God. And by the Contents of this Book” That was the judicial oath I first took in 2003 when I was appointed Second Deemster and again in 2010 when I was appointed First Deemster. I am sharing it with you this evening because it embodies the essentials of the rule of law. Lord Hope, the former Deputy President of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, was kind enough to refer to the Manx judicial oath in the chapter he contributed to Judge and Jurist Essays in Memory of Lord Rodger of Earlsferry (2013 Oxford University Press) at pages 75-76. Justice must be delivered according to the law, without surrendering to any improper influences and delivering equal treatment to everybody, “without respect of favour or friendship, love or gain, consanguinity or affinity, envy or malice”. -

6. Master and Manxman: Reciprocal Plagiarism in Tolstoy and Hall Caine1 Muireann Maguire

M Reading Backwards An Advance Retrospective on Russian Literature READING BACKWARDS EDITED BY MUIREANN MAGUIRE AND TIMOTHY LANGEN An Advance Retrospective This book outlines with theoretical and literary historical rigor a highly innovative approach to the writing of Russian literary history and to the reading of canonical Russian texts. on Russian Literature AGUI —William Mills Todd III, Harvard University Russian authors […] were able to draw their ideas from their predecessors, but also from their successors, R testifying to the open-mindedness that characterizes the Slavic soul. This book restores the truth. E AND —Pierre Bayard, University of Paris 8 This edited volume employs the paradoxical notion of ‘anticipatory plagiarism’—developed in the 1960s L by the ‘Oulipo’ group of French writers and thinkers—as a mode for reading Russian literature. Reversing established critical approaches to the canon and literary influence, its contributors ask us to consider how ANGEN reading against linear chronologies can elicit fascinating new patterns and perspectives. Reading Backwards: An Advance Retrospective on Russian Literature re-assesses three major nineteenth- century authors—Gogol, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy—either in terms of previous writers and artists who ( plagiarized them (such as Raphael, Homer, or Hall Caine), or of their own depredations against later writers EDS (from J.M. Coetzee to Liudmila Petrushevskaia). ) R ) Far from suggesting that past authors literally stole from their descendants, these engaging essays, contributed by both early-career and senior scholars of Russian and comparative literature, encourage us to identify the contingent and familiar within classic texts. By moving beyond rigid notions of cultural heritage and literary canons, they demonstrate that inspiration is cyclical, influence can flow in multiple directions, and no idea is ever truly original. -

The Sophia Morrison & Josephine Kermode

THE SOPHIA MORRISON & JOSEPHINE KERMODE COLLECTION OF MANX FOLK SONGS A PRELIMINARY VIEW One of the difficulties of seeing Sophia Morrison and Josephine Kermode as song collectors is that there are no notebooks full of folk songs nor, say, a bundle of sheets pinned or grouped together to conveniently stand out as being the Morrison and Kermode Collection. There is not, for instance, the four tune books that make up the Clague Collection nor the bound transcript of the Gill brothers collecting to hold reassuringly in the hand. Instead, we have loose sheets scattered amongst her personal papers, others to be found in the hands of Kermode, her close friend and it is argued her fellow-collector. Then there are the song texts published in 1905 in Manx Proverbs and Sayings. And then, remarkably, her sound recordings made with the phonograph of the Manx Language Society purchased in 1904, the cylinders now lost. Morrison stands out as one of the pioneers in Europe in putting the phonograph to use in recording vernacular song culture. It is clear, however, that Morrison’s papers and effects have suffered a considerable loss despite them being in family hands until their eventual deposit in the then Manx Museum Library. One always reads through them with a sense that there was once more— considerably more—and so then they can present us at this date only with a partial view of her activities and that any sense or assessment of her achievements as a collector will ever understate her work. She was active as a folklorist, folk song collector, a promotor of the Manx language, and a Pan Celtic enthusiast of note. -

2012Onhill-Sittings

ON TYNWALD HILL below. The First Deemster sits at the place appointed on the south side of the Hill for His Excellency, the President of Tynwald, the promulgation of the laws in English the Lord Bishop of Sodor and Man, the and the Second Deemster sits in the Attorney General and other Members corresponding position on the north side of the Legislative Council, the Clerk of the Hill for the reading in Manx. The of the Legislative Council, the Persons Deemster, Yn Lhaihder, the Captains of in attendance, the Sword Bearer, the the Parishes, the Coroners and the Deputy Private Secretary to His Excellency and Chief Constable sit on the lowest tier. the Surgeon to the Household will When His Excellency is ready and the occupy the top tier; the Speaker, the officials have taken up their positions on Chief Minister, Members and Secretary the Hill. of the House of Keys together with their Chaplain will be accommodated All stand on the next tier; the High Bailiff, the Representative of the Commission of the THE ROYAL ANTHEM Peace, the Chief Registrar, the Mayor of God save our gracious Queen, Douglas, the Chairmen of the Town and Long live our noble Queen, Village Commissioners, the Archdeacon, God Save the Queen. the Vicar-General, the Clergy, the Roman Send her victorious, Catholic Dean, the representatives of the Happy and glorious, Free Churches, the Salvation Army and Long to reign over us, the Chief Constable will occupy the tier God Save the Queen. TINVAAL • 5.00 JERREY SOUREE 2012 21 All sit They occupy the step below the top step and, when all four are in position on His Excellency says: bended knee, take the following oath, Learned First Deemster, direct the Court administered by the First Deemster: to be fenced. -

220155833.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR RADAR Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Judicial Officers and Advocates of the Isle of Man, 1765-1991 Edge, P (2000) This version is available: https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/2b20d2b0-3d6d-06ab-3090-36635db62328/1/ Available on RADAR: August 2010 Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the original version. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. go/radar www.brookes.ac.uk/ Directorate of Learning Resources Judicial Officers and Advocates of the Isle of Man, 1765-1991. Page created by [email protected], from data gathered in 1992. Page created 1/1/2000, not maintained. Governors and Lieutenant-Governors. 1761 John Wood. (Governor) 1773 Henry Hope. 1775 Richard Dawson. 1777 Edward Smith. (Governor) 1790 Alexander Shaw. 1793 John Murray, Duke of Atholl. (Governor) 1804 Henry Murray. 1805 Colonel Cornelius Smelt. 1832 Colonel Lord Ready. 1845 Charles Hope.