Scrubbing Scales, Saving Trees, Engaging Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Book

NORTH CENTRAL BRANCH Entomological Society of America 59th Annual Meeting March 28-31, 2004 President Rob Wiedenmann The Fairmont Kansas City At the Plaza 401 Ward Parkway Kansas City, MO 64112 Contents Meeting Logistics ................................................................ 2 2003-2004 Officers and Committees, ESA-NCB .............. 4 2004 North Central Branch Award Recipients ................ 8 Program ............................................................................. 13 Sunday, March 28, 2004 Afternoon ...............................................................13 Evening ..................................................................13 Monday, March 29, 2004 Morning..................................................................14 Afternoon ...............................................................23 Evening ..................................................................42 Tuesday, March 30, 2004 Morning..................................................................43 Afternoon ...............................................................63 Evening ..................................................................67 Wednesday, March 31, 2004 Morning..................................................................68 Afternoon ...............................................................72 Author Index ..............................................................73 Taxonomic Index........................................................84 Key Word Index.........................................................88 -

Taxonomic Groups of Insects, Mites and Spiders

List Supplemental Information Content Taxonomic Groups of Insects, Mites and Spiders Pests of trees and shrubs Class Arachnida, Spiders and mites elm bark beetle, smaller European Scolytus multistriatus Order Acari, Mites and ticks elm bark beetle, native Hylurgopinus rufipes pine bark engraver, Ips pini Family Eriophyidae, Leaf vagrant, gall, erinea, rust, or pine shoot beetle, Tomicus piniperda eriophyid mites ash flower gall mite, Aceria fraxiniflora Order Hemiptera, True bugs, aphids, and scales elm eriophyid mite, Aceria parulmi Family Adelgidae, Pine and spruce aphids eriophyid mites, several species Cooley spruce gall adelgid, Adelges cooleyi hemlock rust mite, Nalepella tsugifoliae Eastern spruce gall adelgid, Adelges abietis maple spindlegall mite, Vasates aceriscrumena hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae maple velvet erineum gall, several species pine bark adelgid, Pineus strobi Family Tarsonemidae, Cyclamen and tarsonemid mites Family Aphididae, Aphids cyclamen mite, Phytonemus pallidus balsam twig aphid, Mindarus abietinus Family Tetranychidae, Freeranging, spider mites, honeysuckle witches’ broom aphid, tetranychid mites Hyadaphis tataricae boxwood spider mite, Eurytetranychus buxi white pine aphid, Cinara strobi clover mite, Bryobia praetiosa woolly alder aphid, Paraprociphilus tessellatus European red mite, Panonychus ulmi woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum honeylocust spider mite, Eotetranychus multidigituli Family Cercopidae, Froghoppers or spittlebugs spruce spider mite, Oligonychus ununguis spittlebugs, several -

Scale Insect Pests of Connecticut Trees and Ornamentals

Dr. Hugh Smith, Dr. Richard Cowles, and Rose Hiskes Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8600 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes Scale Insect Pests of Connecticut Trees and Ornamentals Scale insects are among the most difficult mealybug pests of Connecticut ornamentals pests of woody ornamentals to manage. include the taxus mealybug on yew, and the There are several types of scale insect, apple mealybug and the Comstock although the most common scale pests for mealybug, both of which attack many hosts. Connecticut growers are armored scales Common scale pests of Connecticut and (Diaspididae), soft scales (Coccidae) and their hosts are presented in Table 1. mealybugs (Pseudococcidae). Armored scales tend to be smaller (2-3 mm) than soft Life cycle. Depending on the species, scale scales (5-10 mm) and often appear as though insects can overwinter as eggs, immatures, they are part of the plant, making them or adults. Females lay eggs beneath the difficult to detect. Armored scales secrete a scale covering or in a cottony mass. Some hard covering that helps protect them from scale species have one generation per year; insecticides and natural enemies, and some species have a few or several prevents them from drying out. This generations per year. First stage immatures, covering can be pried away from the scale called crawlers, emerge from eggs in spring body with the tip of a blade or an insect pin. -

Scale Insects

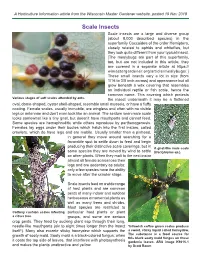

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 19 Nov 2018 Scale Insects Scale insects are a large and diverse group (about 8,000 described species) in the superfamily Coccoidea of the order Hemiptera, closely related to aphids and whitefl ies, but they look quite different from your typical insect. [The mealybugs are part of this superfamily, too, but are not included in this article; they are covered in a separate article at https:// wimastergardener.org/article/mealybugs/.] These small insects vary a lot in size (from 1/16 to 3/8 inch across) and appearance but all grow beneath a wax covering that resembles an individual reptile or fi sh scale, hence the common name. This covering which protects Various stages of soft scales attended by ants. the insect underneath it may be a fl attened oval, dome-shaped, oyster shell-shaped, resemble small mussels, or have a fl uffy coating. Female scales, usually immobile, are wingless and often with no visible legs or antennae and don’t even look like an animal. The seldom seen male scale looks somewhat like a tiny gnat, but doesn’t have mouthparts and cannot feed. Some species are hemaphroditic while others reproduce by parthenogenesis. Females lay eggs under their bodies which hatch into the fi rst instars, called crawlers, which do have legs and are mobile. Usually smaller than a pinhead, in general they move around searching for a favorable spot to settle down to feed and begin producing their distinctive scale coverings, but in A gnat-like male scale some species they are moved by wind to settle (Dactylopius sp.). -

On the Lookout for Scaley Invaders

STEPHEN AUSMUS (K10879-1) most of their lives in one spot extracting plant fluids through a long, thin tube. Meanwhile, tiny male scales have wings and live for just a few days, without ever feeding. It’s their ability to spread quickly, and undetected, to all parts of the world that gets the attention of SEL scientists, es- pecially Miller, who has monitored scales for ARS for 34 years. For about 7 years, he was aided by fellow entomolo- gist Gary Miller, who recently became Entomologists Douglass Miller (foreground) and Gary Miller pull slides from the National SEL’s main aphid scientist. Entomological Collection of the National Museum of Natural History to compare with a scale insect photographic database. They’re Everywhere! Scale insects are most often palaearc- On the Lookout for Scaley Invaders tic in origin, meaning they come from a region that includes Europe, Asia north Knowledge is key to keeping foreign scale insects at bay of the Himalayas, northern Arabia, and Africa north of the Sahara. But today t’s hard enough keeping scale insects invasive scale enters the country, “it’s they are found everywhere, from the tun- out of your garden. Imagine trying important to know its scientific name, dra to the Tropics. I to keep them out of the country! where it comes from, and any other in- At least 1,000 species can be found “They’re small and evasive,” says formation we can get. That way, if we in the United States, 253 of which are entomologist Douglass Miller, lead scale need to implement a biocontrol or pest- invasive. -

SCALE INSECT PESTS GROWING DEGREE DAYS: Base 50 (DDB50) for Immature 'Crawler' Stages

NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE VOL. III DIVISION OF PLANT INDUSTRY NURSERY INSPECTION PROGRAM HORTICULTURAL PESTS OF REGULATORY CONCERN SCALE INSECT PESTS GROWING DEGREE DAYS: Base 50 (DDB50) for Immature 'Crawler' Stages Generations (DDB50) NJ Calendar (Estimates) # Common Name Scientific Name I II III Start Times 1 Azalea Bark Scale Eriococcus azaleae 400-1500 - - June 2 Calico Scale Eulecanium cerasorum 400-1200 - - June 3 Cottony Maple Scale Pulvinaria innumerabilis 802-1265 - - Mid-June 4 Cottony Taxus (Camelia) Scale Chloropulvinaria floccifera 802-1388 - - Mid-June 5 Cryptomeria Scale Aspidiotus cryptomeriae 300-750 2500-3000 - Late-May, Late-August 6 Elongate Hemlock Scale Fiorinia externa 360-700 2515-2625 - Late-May, Late-August 7 Euonymus Scale Unaspis euonymi 533-820 1150-1388 - June, July 8 European Fruit Lecanium Scale Parthenolecanium corni 700-1645 - - Mid-June 9 Fletcher Scale Parthenolecanium fletcheri 1029-1388 2515-2800 - July, Late-August 10 Gloomy Scale Melanaspis tenebricosa 1500-2500 - - Mid-July 11 Golden Oak Scale Asterolecanium variolosum 300-1266 - - Late-May 12 Hemlock Scale Abgrallaspis ithacae 1388-2154 - - July 13 Holly Pit-making Scale Asterodiaspis puteanum 802-1266 - - Late-June 14 Indian Wax Scale Ceroplastes ceriferus 700-1200 - - Mid-June 15 Japanese Maple Scale Lopholeucaspis japonica 500-1600 2000-3000 - June, August 16 Juniper Scale Carulaspis juniperi 707-1260 - - Mid-June 17 Magnolia Scale Neolecanium cornuparvum 246-448 2155-2800 - May, August 18 Maskell Scale Leepidosaphes pallida 700 -

Host Plant List of the Scale Insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) in South Korea

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 3-27-2020 Host plant list of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) in South Korea Soo-Jung Suh Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. March 27 2020 INSECTA 26 urn:lsid:zoobank. A Journal of World Insect Systematics org:pub:FCE9ACDB-8116-4C36- UNDI M BF61-404D4108665E 0757 Host plant list of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) in South Korea Soo-Jung Suh Plant Quarantine Technology Center/APQA 167, Yongjeon 1-ro, Gimcheon-si, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea 39660 Date of issue: March 27, 2020 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Soo-Jung Suh Host plant list of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) in South Korea Insecta Mundi 0757: 1–26 ZooBank Registered: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:FCE9ACDB-8116-4C36-BF61-404D4108665E Published in 2020 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P.O. Box 141874 Gainesville, FL 32614-1874 USA http://centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non- marine arthropod. Topics considered for publication include systematics, taxonomy, nomenclature, checklists, faunal works, and natural history. Insecta Mundi will not consider works in the applied sciences (i.e. -

New Parasitoids Records of Eulecanium Rugulosum (Archangelskaya, 1937) (Hemiptera:Sternorrhyncha:Coccoidea: Coccidae) for Diyarbakır

Türk. Biyo. Mücadele Derg. 2019, 10 (2):133-141 DOI: 10.31019/tbmd. 589239 ISSN 2146-0035-E-ISSN 2548-1002 Orijinal araştırma (Original article) New Parasitoids Records of Eulecanium rugulosum (Archangelskaya, 1937) (Hemiptera:Sternorrhyncha:Coccoidea: Coccidae) for Diyarbakır Halil BOLU1* Diyarbakır için Eulecanium rugulosum’un (Archangelskaya, 1937) (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea: Coccidae) yeni kayıt parazitoidleri Abstract: This study was carried out in Diyarbakır, Turkey in 2014 on parasitoids of the coccid, Eulecanium rugulosum (Archangelskaya, 1937) (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea: Coccidae), infesting the pistachio tree, Pistacia vera Linnaeus (Sapindales: Anacardiaceae). During this study, three parasitoid species, Blastothrix brittanica Girault 1917, Blastothrix longipennis Howard, 1881 and Blastothrix sericea Dalman, 1820 (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae: Encyrtinae), were collected. These are the first reports from Diyarbakır of the association between these parasitoids and E. rugulosum. Key words: Eulecanium rugulosum, Blastothrix brittanica, B. longipennis, B. sericea, new record, Diyarbakır Özet: Bu çalışma, Eulecanium rugulosum (Archangelskaya, 1937) (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea: Coccidae) ile bulaşık Antepfıstığı ağaçlarında (Pistacia vera Linnaeus) 2014-2015 yılları arasında Diyarbakır ilinde yürütülmüştür. Çalışma sonucunda zararlıdan 3 parazitoid türü elde edilmiştir. Bu türler: Blastothrix brittanica Girault 1917; Blastothrix longipennis Howard, 1881 ve Blastothrix sericea Dalman, 1820 (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae: -

A Survey of Key Arthropod Pests on Common Southeastern Street Trees

Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 45(5): September 2019 155 Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 2019. 45(5):155–166 ARBORICULTURE URBAN FORESTRY Scientific Journal of the International& Society of Arboriculture A Survey of Key Arthropod Pests on Common Southeastern Street Trees By Steven D. Frank Abstract. Cities contain dozens of street tree species each with multiple arthropod pests. Developing and implementing integrated pest management (IPM) tactics, such as scouting protocols and thresholds, for all of them is untenable. A survey of university research and extension personnel and tree care professionals was conducted as a first step in identifying key pests of common street tree genera in the Southern United States. The survey allowed respondents to rate seven pest groups from 0 (not pests) to 3 (very important or damaging) for each of ten tree genera. The categories were sucking insects on bark, sucking insects on leaves, defoliators and leafminers, leaf and stem gall forming arthropods, trunk and twig borers and bark beetles, and mites. Respondents could also identify important pest species within categories. Some tree genera, like Quercus and Acer, have many important pests in multiple categories. Other genera like Lirioden- dron, Platanus, and Lagerstroemia have only one or two key pests. Bark sucking insects were the highest ranked pests of Acer spp. Defo- liators, primarily caterpillars, were ranked highest on Quercus spp. followed closely by leaf and stem gallers, leaf suckers, and bark suckers. All pest groups were rated below ‘1’ on Zelkova spp. Identifying key pests on key tree genera could help researchers prioritize IPM development and help tree care professionals prioritize their training and IPM implementation. -

Factors Influencing Insecticide Efficacy Against Armored and Soft Scales

Frank, 2014; Meineke et al., 2014). Factors Influencing Insecticide Efficacy against Individuals tasked with protecting Armored and Soft Scales trees from scale insects in urban envi- ronments need to select and time pesticide applications so they target 1 Carlos R. Quesada , Adam Witte, and Clifford S. Sadof the most susceptible stages of scales while minimizing impact on natural enemies (Cloyd, 2010; Frank, 2012; ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. pine needle scale, oleander scale, calico scale, striped pine scale, chemical control, crawler duration Rebek and Sadof, 2003; Robayo- Camacho and Chong, 2015). As SUMMARY. Scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) are among the most economically such, pesticides that have been cate- important pests of ornamental plants. Soft scales (Coccidae) are phloem-feeding gorized by the U.S. Environmental insects that produce large amounts of honeydew. By contrast, armored scales (Diaspididae) feed on the contents of plant cells and produce a waxy test that covers Protection Agency (EPA) as reduced their bodies. We studied two species of armored scales [pine needle scale (Chionaspis risk to human health and the environ- pinifoliae) and oleander scale (Aspidiotus nerii)] and two species of soft scales [calico ment are favorable candidates for use scale (Eulecanium cerasorum) and striped pine scale (Toumeyella pini)] to compare in a pest management program (EPA, efficacy of selected insecticides. In addition, we assessed how the duration of first 2010). Although applications of re- instar emergence might influence insecticide efficacy. Several reduced-risk insecti- duced-risk products to the crawling cides (chlorantraniliprole, pyriproxyfen, spiromesifen, and spirotetramat), horti- scales can be as effective as those culture oil, and two broad-spectrum insecticide standards (bifenthrin and products with higher risk chemistries dinotefuran) were evaluated. -

Maples Choose Their Battles Against Common Insect and Mite Pests

VOL. 43/NO. 2 FALL 2012 The Official Publication of The Kentucky Nursery and Landscape Association Maples Choose Their Battles Against Common Insect and Mite Pests EConoMIC IMPACTs of the Kentucky Green Industry: Wholesale and Retail Trade Stressed Plants More Susceptible to BlACK rooT roT Plus, snapshots from KNLA's 2012 Summer Outing Cov Er sTory / PEsT sPoTLIgHT Maples Choose Their Battles Against Common Insect and Mite Pests By Sarah J. Vanek, Bonny L. Seagraves and Daniel A. Potter, University of Kentucky Young maple trees are particularly vulnerable to insect and mite pests, but landscape and nursery managers can use built-in plant defenses to their advantage. aples are highly popular trees that represent a significant portion of the market for deciduous M shade trees in Kentucky. At any given time, large wholesale tree farms in Kentucky can have thousands of ma- ples in production. In 2009, maples collectively accounted for an estimated 41% of wholesale sales for deciduous shade trees in Kentucky; the most valuable species, red maple, alone ac- counted for approximately 26% of sales. Maples are popular trees because of their aesthetic qualities, which include attractive fall colors and uniform shape. They also tend to be relatively pest-free trees once established in the landscape. Young maple trees, however, are particularly vulnerable to certain pest attacks, leading to disfigurement, stunted growth or even death. Tree loss and distorted tree growth cost nursery and landscape managers time and money. Plants have adopted various methods for defending them- selves against insect and other pest attacks. These defenses include chemical and physical defenses, and they vary between plant species and cultivars. -

Biology, Injury, and Management of Maple Tree Pests in Nurseries and Urban Landscapes S

Biology, Injury, and Management of Maple Tree Pests in Nurseries and Urban Landscapes S. D. Frank,1,2 W. E. Klingeman, III,3 S. A. White,4 and A. Fulcher3 1Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected]. 2NC State University, Department of Entomology, 3318 Gardner Hall, Raleigh, NC 27965-7613. 3University of Tennessee Knoxville, Department of Plant Sciences. 4Clemson University, Department of Environmental Horticulture. J. Integ. Pest Mngmt. 4(1): 2013; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/IPM12007 ABSTRACT. Favored for their rapid growth and brilliant fall color, maple (Acer spp.) trees are among the most commonly grown deciduous shade trees in urban landscapes and commercial production nurseries. Many maple species used as ornamental plants share a suite of important arthropod pests that have the potential to reduce the trees’ economic and esthetic value. We review the biology, damage, and management for the most important pests of maples with emphasis on integrated pest management (IPM) tactics available for each pest. Unfortunately, the biology of some of these pests is not well studied. This knowledge gap, paired with the low esthetic threshold for damage on ornamental plants, has hindered development of IPM tactics for maple pests in nurseries and landscapes. Maples will likely remain a common landscape plant. Therefore, our challenge is to improve IPM of the diverse maple pest complex. Key Words: Acer spp., arthropod, integrated pest management, key pest, ornamental plants Maple (Acer) is the most common genus of deciduous street tree management (IPM) adoption by pest managers, including develop- planted in eastern North America (Raupp et al.