15. Retransmission of Free-To-Air Broadcasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION TO ANY U.S. PERSON OR TO ANY PERSON OR ADDRESS IN THE U.S. Important: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the Offering Circular following this page, and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Offering Circular. In accessing the Offering Circular, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE NOTES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE U.S. SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE “SECURITIES ACT”), OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE U.S. OR OTHER JURISDICTION AND THE NOTES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF U.S. PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT), EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM, OR IN A TRANSACTION NOT SUBJECT TO, THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE SECURITIES ACT AND APPLICABLE STATE OR LOCAL SECURITIES LAWS. THE FOLLOWING OFFERING CIRCULAR MAY NOT BE FORWARDED OR DISTRIBUTED TO ANY OTHER PERSON AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED IN ANY MANNER WHATSOEVER, AND IN PARTICULAR, MAY NOT BE FORWARDED TO ANY U.S. PERSON OR TO ANY U.S. ADDRESS. -

Virgin Atlantic

Virgin Atlantic Cryptocurrencies: Provisional Lottie Pyper considers the 2020 and beyond Liquidation and guidance given on the first Robert Amey, with Restructuring: Jonathon Milne of The Cayman Islands restructuring plan under Conyers, Cayman, and Hong Kong Part 26A of the Companies on recent case law Michael Popkin of and developments Campbells, takes a Act 2006 in relation to cross-border view cryptocurrencies A regular review of news, cases and www.southsquare.com articles from South Square barristers ‘The set is highly regarded internationally, with barristers regularly appearing in courts Company/ Insolvency Set around the world.’ of the Year 2017, 2018, 2019 & 2020 CHAMBERS UK CHAMBERS BAR AWARDS +44 (0)20 7696 9900 | [email protected] | www.southsquare.com Contents 3 06 14 20 Virgin Atlantic Cryptocurrencies: 2020 and beyond Provisional Liquidation and Lottie Pyper considers the guidance Robert Amey, with Jonathon Milne of Restructuring: The Cayman Islands given on the first restructuring plan Conyers, Cayman, on recent case law and Hong Kong under Part 26A of the Companies and developments arising from this Michael Popkin of Campbells, Act 2006 asset class Hong Kong, takes a cross-border view in these two off-shore jurisdictions ARTICLES REGULARS The Case for Further Reform 28 Euroland 78 From the Editors 04 to Strengthen Business Rescue A regular view from the News in Brief 96 in the UK and Australia: continent provided by Associate South Square Challenge 102 A comparative approach Member Professor Christoph Felicity -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ANANDA KRISHNAN PROFILE AND BACKGROUND 3 - 8 MAXIS COMMUNICATION COMPANY PROFILE 9 - 12 ASTRO COMPANY PROFILE 13 - 20 STYLE OF LEADERSHIP 21 - 24 LEADERSHIP THEORY ADAPTATION 25 Conclusion 26 References 27 1 (a) Background of the leader: the aim of this section is to know and understand the leader as a person and the bases for his/her success. The data and information should be taken from any published sources such as newspapers, company reports, magazines, journals, books etc. INTRODUCTION ANANDA KRISHNAN Who is Ananda Krishnan? According to a report then by Bernama News Agency, the grandfathers of Tan Sri T. Ananda Krishnan and Tan Sri G. Gnanalingam had been brought to Malaysia from Jaffna by British colonial rulers to work in Malaysia¶s Public Works Department, a common practice then as Jaffna produced some of the most educated people in the whole country. Tan Sri Gnanalingam himself told one of our ministers that he wants to put something back into this country because his grandfather was Sri Lankan," Deputy Director-General of Sri Lanka's Board of Investment (BOI) Santhusht Jayasuriya had told a a group of visiting Malaysian journalists then, 2 according to the Bernama 2003 story. Gnanalingam, executive chairman of Malaysia's Westport, held talks with Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe during a visit to Malaysia in 2003 and the former followed up with a visit to Colombo. In the same year a Memorandum of Understanding was formalized in March this year between 'Westport' and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA). Westport is keen to invest in Sri Lanka but no formal process has begun. -

Report for 2Degrees and TVNZ on Vodafone/Sky Merger

Assessing the proposed merger between Sky and Vodafone NZ A report for 2degrees and TVNZ Grant Forsyth, David Lewin, Sam Wood August 2016 PUBLIC VERSION Plum Consulting, London T: +44(20) 7047 1919, www.plumconsulting.co.uk PUBLIC VERSION Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 The applicants’ argument for allowing the merger .................................................................... 6 1.2 The structure of our report ........................................................................................................ 6 2 The state of competition in New Zealand ....................................................................................... 8 2.1 The retail pay TV market ........................................................................................................... 8 2.2 The retail fixed broadband market ..........................................................................................10 2.3 The retail mobile market..........................................................................................................12 2.4 The wholesale pay TV market ................................................................................................13 2.5 New Zealand’s legal and regulatory regimes ..........................................................................14 -

Thailand's Pay TV Sector

Thailand in View: Thai Pay-TV 2011 Executive Summary A CASBAA market report January 2011 Thailand in View 2011 provides an in-depth review of the cable and satellite TV market, now connecting to more than 50% of homes in Thailand. An essential resource for anyone seeking concise and current analysis of the industry today and the outlook moving forward. Don’t miss the full report for CASBAA members at www.casbaa.com/publications. Executive Summary Growth of free-to-air satellite TV From only a few channels in 2008, Thailand now has Expanding reach of cable and satellite TV in Thailand more than 100 FTA channels broadcast on satellite platforms, and the number keeps on growing. Thailand’s cable and satellite TV sector experienced Leading operators and content providers plan to tremendous growth as viewing households more launch a total number of 40-50 new channels with than tripled from 2.67 million in 2007 to 9.33 million a wide variety of programming content including in mid 2010, as measured by Nielsen. By the end edutainment, local documentaries, musical of 2010, the number is estimated to have risen varieties, public relations channels (sponsored by further to over 10 million households, for nearly 50% government agencies), lifestyle, home & food, and penetration. other entertainment channels – with each channel targeting a specific audience segment. Indeed, between 2007 and 2010, cable and satellite The decision by premium player TrueVisions to TV viewership grew on average 52 percent each year join this arena further underscores the intensity of with rural areas showing the most rapid expansion competition on this TV platform. -

Complaints Dealt with by the Communications Authority (“CA”) (Released on 15 December 2020)

Complaints dealt with by the Communications Authority (“CA”) (released on 15 December 2020) The CA considered the following cases which had been deliberated by the Broadcast Complaints Committee (“BCC”) – Complaint Cases 1. Television Programme “Another Hong Kong” (另一個香港) broadcast by Television Broadcasts Limited (“TVB”), PCCW Media Limited (“now TV”), Hong Kong Cable Television Limited (“HKCTV”) and Radio Television Hong Kong (“RTHK”) 2. Radio Programmes “Weekend Lucky Star” (潮爆開運王) broadcast by Hong Kong Commercial Broadcasting Company Limited (“CRHK”) The CA also considered cases of dissatisfaction with the decisions of the Director-General of Communications (“DG Com”) on complaint cases. Having considered the recommendations of the BCC, the CA decided– 1. that the complaints against the television programme “Another Hong Kong” (另 一個香港) were unsubstantiated. Nevertheless, there is scope to improve identification of the source of acquired/relayed factual programmes on controversial issues of public importance in Hong Kong to help viewers in making decisions in their choice of programmes and in forming their expectations and judgements. The CA suggested that TVB could inform viewers of the existence of other parts of such programmes which were not broadcast on its service, and that now TV and HKCTV should provide sufficient information about the source of such programmes in a prominent manner prior to their broadcast; 2. that strong advice should be given to CRHK on the complaint against the radio programmes “Weekend Lucky Star” (潮爆開運王); and 3. to uphold the decisions of the DG Com on two cases of dissatisfaction with the decisions of the DG Com. The list of the cases is available in the Appendix. -

Thailand in View a CASBAA Market Research Report

Thailand in View A CASBAA Market Research Report Executive Summary 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Pay-TV environment market competition from satellite TV, and perceived unfair treatment by the National Broadcasting and The subscription TV market experienced a downturn Telecommunications Commission, whose very broad in 2014 as a result of twin events happening almost “must carry” rule created a large cost burden on simultaneously: the launch of DTT broadcasting in operators (particularly those that still broadcast on an April 2014 increased the number of free terrestrial TV analogue platform). stations from six to 24 commercial and four public TV broadcasters, leading to more intense competition; and Based on interviews with industry leaders, we estimate the military takeover in May 2014 both created economic that in 2015 the overall pay-TV market contracted by uncertainty and meant government control and three percent with an estimated value of around US$465 censorship of the media, prohibiting all media platforms million compared to US$480 million the previous from publishing or broadcasting information critical of year. Despite the difficult environment, TrueVisions, the military’s actions. the market leader, posted a six percent increase in revenue year-on-year. The company maintained its The ripple effects of 2014’s events continue to be felt by leading position by offering a wide variety of local and the industry two years after. By 2015/2016, the number of international quality content as well as strengthening licensed cable TV operators had decreased from about its mass-market strategy to introduce competitive 350 to 250 because of the sluggish economy, which convergence campaigns, bundling TV with other suppressed consumer demand and purchasing power, products and services within True Group. -

HKTV Has Finally Made Its Long-Awaited Debut Online. Arthur

Licence to thrill HKTV has finally made its long-awaited debut online. Arthur Tam goes outside the box and finds out what it means for the future of IM MCEVENUE T television in our city ILLUSTRATION BY BY ILLUSTRATION 28 timeout.com.hk esides being a hub for the finance, dropped in recent years,” he counters. Commerce and Economic Development, fashion and film industries over “But this is also due to the fact that people Greg So Kam-leung, has revealed any Bthe years, Hong Kong also has a have switched to different devices for sort of answer after he stated that a proud history in TV. The city’s thriving viewing. If you add it all up, there is consultant’s report – not released to the television scene has been an undying actually an increase in viewership.” public – claimed that Hong Kong couldn’t source of cultural influence – both locally sustain more than four TV stations. and internationally. It’s nothing short The days that followed last year’s of amazing that a small territory with rejection saw public outcry. Angry a market of just seven million people TV viewers called for the government can regularly produce TV shows with to be transparent about its decision. budgets similar to those made in the WE ARE THE An estimated 100,000 people amassed US that have a market of more than 300 outside the Legislative Council in protest million people. Ever since the conception VICTIMS OF OUR on October 20. So, not one to give up, of HK’s first free-to-air station, TVB, Wong then made a move to acquire China which launched on November 19, OWN SUCCESS Mobile Hong Kong for $142 million and 1967, we’ve been producing quality just proceeded to forge ahead with his TV programming that not only reaches local With the stage set and audiences network regardless. -

Tvb Television Broadcasts of Hong Kong Selects Eutelsat Eurobird™ 9 Satellite for New Multi-Channel Chinese Platform for Europe

PR/21/08 TVB TELEVISION BROADCASTS OF HONG KONG SELECTS EUTELSAT EUROBIRD™ 9 SATELLITE FOR NEW MULTI-CHANNEL CHINESE PLATFORM FOR EUROPE Paris, 11 June 2008 Television Broadcasts Ltd (TVB) of Hong Kong, one of the world’s largest producers and distributors of Chinese programmes, has selected capacity on the EUROBIRD™ 9 satellite operated by Eutelsat Communications (Euronext Paris: ETL) to launch its new multi-channel digital platform of Chinese-language channels for satellite homes across Europe. For the first time in Europe, TVB’s subsidiary ‘The Chinese Channel’ is offering a line-up of five of the Group’s flagship infotainment channels including “TVBS-Europe” which specialises in Hong Kong drama series, local news and Chinese community events in Europe. It also comprises four speciality channels which were launched in first quarter 2008: “TVBN”, a 24-hour Hong Kong and global news channel, “TVB Entertainment News” which focuses on entertainment news from Hong Kong, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Europe and the USA, “TVB Classic” which shows nostalgic content, and “TVB Lifestyle” which specialises in fashion, travel and dining. The channels are broadcast in Cantonese and uplinked to EUROBIRD™ 9 by Eutelsat’s Skylogic affiliate from its teleport in Turin. Using the slogan “Give me Five!”, The Chinese Channel is targeting the population of half a million Cantonese speakers within EUROBIRD™ 9’s pan-European footprint. Anthony Ho, Controller of the Overseas Satellite Operations Division of TVB said: “We are delighted to be associated with Eutelsat as our partner in this venture. To achieve our milestones, Eutelsat provided considerable technical assistance and advice to TVB, enabling the five channels to be on air in less than three months. -

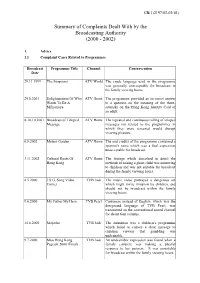

Summary of Complaints Dealt with by the Broadcasting Authority (2000 - 2002)

CB(1)2197/02-03(01) Summary of Complaints Dealt With by the Broadcasting Authority (2000 - 2002) 1. Advice 1.1 Complaint Cases Related to Programmes Broadcast Programme Title Channel Contravention Date 29.11.1999 The Simpsons ATV World The crude language used in the programme was generally unacceptable for broadcast in the family viewing hours. 29.8.2001 Enlightenment Of Who ATV Home The programme provided an incorrect answer Wants To Be A to a question on the meaning of the three- Millionaire asterisks on the Hong Kong Identity Card of an adult. 8-10.10.2001 Broadcast of Teloped ATV Home The repeated and continuous rolling of teloped Message messages not related to the programmes in which they were screened would disrupt viewing pleasure. 6.8.2002 Meteor Garden ATV Home The end credits of the programme contained a sponsor's name which was a foul expression unacceptable for broadcast. 3.11.2002 Cultural Roots Of ATV Home The footage which described in detail the Hong Kong methods of raising a ghost child was unnerving to children and was not suitable for broadcast during the family viewing hours. 8.5.2000 J.S.G. Song Video TVB Jade The music video portrayed a dangerous act Corner which might invite imitation by children, and should not be broadcast within the family viewing hours. 9.6.2000 My Father My Hero TVB Pearl Cantonese instead of English, which was the designated language of TVB Pearl, was transmitted on the conventional sound channel for about four minutes. 14.6.2000 Mojacko TVB Jade The animation was a children’s programme which failed to convey a clear message to children viewers that gambling was undesirable. -

As Filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on October 11, 1996

AS FILED WITH THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ON OCTOBER 11, 1996 REGISTRATION NO. 333-10875 - ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- - ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 ------------------ AMENDMENT NO. 1 TO FORM S-1 REGISTRATION STATEMENT UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 ------------------ PRIMUS TELECOMMUNICATIONS GROUP, INCORPORATED (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 4813 54-1708481 (STATE OR OTHER (PRIMARY STANDARD (I.R.S. EMPLOYER JURISDICTION OF INDUSTRIAL IDENTIFICATION NO.) INCORPORATION OR CLASSIFICATION CODE ORGANIZATION) NUMBER) 8180 GREENSBORO DRIVE SUITE 1100 MCLEAN, VIRGINIA 22102 (703) 848-4625 (ADDRESS, INCLUDING ZIP CODE, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE, OF REGISTRANT'S PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) ------------------ K. PAUL SINGH CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 8180 GREENSBORO DRIVE SUITE 1100 MCLEAN, VIRGINIA 22102 (703) 848-4625 (NAME, ADDRESS, INCLUDING ZIP CODE, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE, OF AGENT FOR SERVICE) ------------------ COPIES TO: JAMES D. EPSTEIN, ESQ. DAVID J. BEVERIDGE, ESQ. PEPPER, HAMILTON & SCHEETZ SHEARMAN & STERLING 3000 TWO LOGAN SQUARE 599 LEXINGTON AVENUE PHILADELPHIA, PA 19103-2799 NEW YORK, NY 10022 (215) 981-4000 (212) 848-4000 ------------------ APPROXIMATE DATE OF COMMENCEMENT OF PROPOSED SALE TO THE PUBLIC: As soon as practicable after this Registration Statement becomes effective. ------------------ If any of the securities being registered on this Form are to be offered on a delayed or continuous basis pursuant to Rule 415 under the Securities Act of 1933, check the following box. [_] If this Form is filed to register additional securities for an offering pursuant to Rule 462(b) under the Securities Act, please check the following box and list the Securities Act registration statement number of the earlier effective registration statement for the same offering. -

Vod/ Ott Industry in Apac

MARKET STUDY REPORT ON IPTV/ VOD/ OTT INDUSTRY IN APAC September 2017 1 Research by IBC Consultants (www.consult-ibc.com) Contents Executive Summary....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Description – What is IPTV, VOD and OTT? .......................................................................... 4 IPTV ........................................................................................................................................ 4 VOD ......................................................................................................................................... 5 OTT .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Value Chain .......................................................................................................................... 7 Market Overview: Global ............................................................................................................................ 8 Market Overview: Asian Countries ....................................................................................................... 11 Market Segmentation ................................................................................................................................