Experiences and Perceptions of Broadway Costume Designers Sara Jablon Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

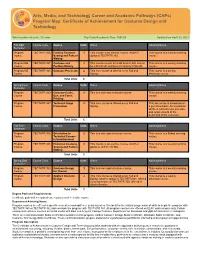

Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology

Arts, Media, and Technology Career and Academic Pathways (CAPs) Program Map: Certificate of Achievement for Costume Design and Technology Total number of units: 23 units Top Code/Academic Plan: 1006.00 Updated on April 25, 2021 Fall Odd Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 366 Fantasy Costume 3 This course is an elective course. Another This course is a weekly morning Course Sewing and Pattern option is TECTHTR 365. course. Making Program/GE TECTHTR 367 Costume and 3 This course counts as a GE Area C Arts course This course is a weekly morning Course Fashion History for LACCD GE and Area C1 Arts for CSU GE. course. Program/GE TECTHTR 345 Costume Practicum 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This course is a weekly Course Spring. afternoon course. Total Units 8 Spring Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 363 Costume Crafts, 3 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a weekly morning Course Dye, and Fabric course. Printing Program TECTHTR 342 Technical Stage 2 This core course is offered every Fall and This lab course is scheduled on Course Production Spring. a per show basis. An orientation will be held to discuss schedule and requirements at the beginning of the semester. Total Units 5 Fall Even Course Code Course Units Notes Advising Notes Semester Program TECTHTR 305 Orientation to 2 This is a core and milestone course. This course is a Friday morning Course Technical Careers course. in Entertainment Program TECTHTR 365 Historical Costume 3 This course is an elective course. -

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

~La6(8Ill COMPA.NIES INC

October 1999 Brooklyn Academy of Music 1999 Next Wave Festival BAMcinematek Brooklyn Philharmonic 651 ARTS ~' pi I'" T if II' II i fl ,- ,.. til 1 ~ - - . I I I' " . ,I •[, II' , 1 , i 1'1 1/ I I; , ~II m Jennifer Bartleli, House: Large Grid, 1998 BAM Next Wave Festival sponsored by PHILIP MORRIS ~lA6(8Ill COMPA.NIES INC. Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Prod ucer presents Moby Dick Running time: BAM Opera House approximately ninety October 5, 1999, at 7:00 p.m. (Next Wave Festival Gala) minutes. Songs and October 6-9 & 12-16, 1999, at 7:30 p.m. Stories from Moby Dick is performed without an Visual Design, Music, and Lyrics Laurie Anderson intermission. Performers Pip, The Whale, A Reader Laurie Anderson Ahab, Noah, Explorer Tom Nelis The Cook, Second Mate, Running Man Price Waldman Standing Man Anthony Turner Falling Man Miles Green Musicians Violin, keyboards, guitar, talking stick Laurie Anderson Bass, prepared bass, samples Skuli Sverrisson Artistic Collaborators Co-Visual Design Christopher Kondek Co-Set Design James Schuette Lighting Design Michael Chybowski Sound Design Miles Green Costume Design Susan Hilferty Electronics Design Bob Bielecki Video Systems Design Ben Rubin Staging Co-Direction Anne Bogart General Management Julie Crosby Production Management Bohdan Bushell Production Stage Management Lisa Porter Major support for this presentation was provided by The Ford Foundation with additional support from The Dime Savings Bank of New York, FSB. Next Wave Festival Gala is sponsored by Philip Morris Companies Inc. 17 Produced by electronic theater company, Inc. -

Legally Blonde: Introduction

Being true to yourself never goes out of style! WINNER BEST NEW MUSICAL 2011 OLIVIER AWARD EDUCATION KIT AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE SEASON • SYDNEY LYRIC LegallyBlonde.com.au facebook.com/ legallyblondemusical @legallyblondeoz Legally Blonde: INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION This teacher’s guide has been developed as a teaching tool to assist teachers who are bringing their students to see the show. This guide is based on Camp Broadway’s StageNOTES, conceived for the original Broadway musical adaptation of Amanda Brown’s 2001 novel and the film released that same year, and has been adapted for use within the UK and Australia. The Australian Education Pack is intended to offer some pathways into the production, and focuses on some of the topics covered in Legally Blonde which may interest students and teachers. It is not an exhaustive analysis of the musical or the production, but instead aims to offer a variety of stimuli for debate, discussion and practical exploration. It is anticipated that the Education Pack will be best utilised after a group of students have seen the production with their teacher, and can engage in an informed discussion based on a sound awareness of the musical. We hope that the information provided here will both enhance the live theatre experience and provide readers with information they may not otherwise have been able to access. Legally Blonde is an uplifting, energising, feel-good show and with that in mind we hope this pack will be enjoyed through equally energising and enjoyable practical work in the classroom and drama studio. 1 Legally Blonde: INTRODUCTION LEgally Blonde Education Pack CONTENTS PAGE INTODUCTION 1. -

Tragedy, Realism, Skepticism

Tragedy, Realism, Skepticism BENJAMIN MANGRUM Many current accounts of the relationship between tragedy and modern realism present these generic traditions as not only distinct but even rigidly opposed. Critics who trace the advent of modern realism — most often through the rise of the novel — have maintained that its origins lie in the development of the middle class, the transformation of the medieval romance, the global dissemination of European civilization, or the consolidation of bourgeois ideology and subjectivity (see McKeon 2002, 52 – 63; Davidson 2004, 73 – 100; Azim 1993; Viswanathan 1989, 23 – 44). In these literary histories, the generic formation of the realist novel is the antithesis to the history of “tragic” literary forms. Indeed, the cursory dif- ference between a lengthy (prose) narrative and a concentrated (poetic) drama masks a host of tensions. The novel narrativizes middle-class values, whereas tragedies stage the fall of aristocratic or “great” houses; the realist novel purport- edly democratizes literature, while tragedies regularly presuppose some form of antipathy toward the mundane or lower classes (see Aristotle 1999, 35); a “real- ist” or secular view of history underlies the novel, while tragedy seems to enfold human agency within the forces of divine fate;1 the novel protracts drama across time, whereas tragedy intensifies it into momentous events;2 the novel is con- cerned with subjectivity (see Armstrong 2006), while tragedy explores the dis- solution of the individual, the doxastic wisdom of the chorus, or the demands of 1. In The Historical Novel (1983), Georg Lukács situates the works of Sir Walter Scott within the production of bourgeois consciousness and a view of history that contrasts sharply with its precursors, the epic and tragedy. -

Puvunestekn 2

1/23/19 Costume designers and Illustrations 1920-1940 Howard Greer (16 April 1896 –April 1974, Los Angeles w as a H ollywood fashion designer and a costume designer in the Golden Age of Amer ic an cinema. Costume design drawing for Marcella Daly by Howard Greer Mitc hell Leis en (October 6, 1898 – October 28, 1972) was an American director, art director, and costume designer. Travis Banton (August 18, 1894 – February 2, 1958) was the chief designer at Paramount Pictures. He is considered one of the most important Hollywood costume designers of the 1930s. Travis Banton may be best r emembered for He held a crucial role in the evolution of the Marlene Dietrich image, designing her costumes in a true for ging the s tyle of s uc h H ollyw ood icons creative collaboration with the actress. as Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae Wes t. Costume design drawing for The Thief of Bagdad by Mitchell Leisen 1 1/23/19 Travis Banton, Travis Banton, Claudette Colbert, Cleopatra, 1934. Walter Plunkett (June 5, 1902 in Oakland, California – March 8, 1982) was a prolific costume designer who worked on more than 150 projects throughout his career in the Hollywood film industry. Plunk ett's bes t-known work is featured in two films, Gone with the Wind and Singin' in the R ain, in which he lampooned his initial style of the Roaring Twenties. In 1951, Plunk ett s hared an Osc ar with Orr y-Kelly and Ir ene for An Amer ic an in Paris . Adr ian Adolph Greenberg ( 1903 —19 59 ), w i de l y known Edith H ead ( October 28, 1897 – October 24, as Adrian, was an American costume designer whose 1981) was an American costume designer mos t famous costumes were for The Wiz ard of Oz and who won eight Academy Awards, starting with other Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and The Heiress (1949) and ending with The Sting 1940s. -

THTR 433A/ '16 CD II/ Syllabus-9.Pages

USCSchool of Costume Design II: THTR 433A Thurs. 2:00-4:50 Dramatic Arts Fall 2016 Location: Light Lab/PDE Instructor: Terry Ann Gordon Office: [email protected]/ floating office Office Hours: Thurs. 1:00-2:00: by appt/24 hr notice Contact Info: [email protected], 818-636-2729 Course Description and Overview This course is designed to acquaint students with the requirements, process and expectations for Film/TV Costume Designers, supervisors and crew. Emphasis will be placed on all aspects of the Costume process; Design, Prep: script analysis,“scene breakdown”, continuity, research, and budgeting; Shooting schedules, and wrap. The supporting/ancillary Costume Arts and Crafts will also be discussed. Students will gain an historical overview, researching a variety of designers processes, aesthetics and philosophies. Viewing films and film clips will support critique and class discussion. Projects focused on specific design styles and varied media will further support an overview of techniques and concepts. Current production procedures, vocabulary and technology will be covered. We will highlight those Production departments interacting closely with the Costume Department. Time permitting, extra-curricular programs will include rendering/drawing instruction, select field trips, and visiting TV/Film professionals. Students will be required to design a variety of projects structured to enhance their understanding of Film/TV production, concept, style and technique . Learning Objectives The course goal is for students to become familiar with the fundamentals of costume design for TV/Film. They will gain insight into the protocol and expectations required to succeed in this fast paced industry. We will touch on the multiple variations of production formats: Music Video, Tv: 4 camera vs episodic, Film, Commercials, Styling vs Costume Design. -

Love's Labour's Lost

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS CAST Wednesday, November 4, 2009, 8pm Love’s Labour’s Lost Thursday, November 5, 2009, 7pm Friday, November 6, 2009, 8pm Saturday, November 7, 2009, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, November 8, 2009, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Shakespeare’s Globe in Love’s Labour’s Lost John Haynes CAST by William Shakespeare Ferdinand, King of Navarre Philip Cumbus Berowne Trystan Gravelle Artistic Director for Shakespeare‘s Globe Dominic Dromgoole Longaville William Mannering Dumaine Jack Farthing Director Set and Costume Designer Composer The Princess of France Michelle Terry Dominic Dromgoole Jonathan Fensom Claire van Kampen Rosaline Thomasin Rand Choreographer Fight Director Lighting Designer Maria Jade Anouka Siân Williams Renny Krupinski Paul Russell Katherine Siân Robins-Grace Text Work Movement Work Voice Work Boyet, a French lord in attendance on the Princess Tom Stuart Giles Block Glynn MacDonald Jan Haydn Rowles Don Adriano de Armado, a braggart from Spain Paul Ready Moth, his page Seroca Davis Holofernes, a schoolmaster Christopher Godwin Globe Production Manager U.S. Production Manager Paul Russell Bartolo Cannizzaro Sir Nathaniel, a curate Patrick Godfrey Dull, a constable Andrew Vincent U.S. Press Relations General Management Richard Komberg and Associates Paul Rambacher, PMR Productions Costard, a rustic Fergal McElherron Jaquenetta, a dairy maid Rhiannon Oliver Executive Producer, North America Executive Producer for Shakespeare’s Globe Eleanor Oldham and John Luckacovic, Conrad Lynch Other parts Members of the Company 2Luck Concepts Musical Director, recorder, shawms, dulcian, ocarina, hurdy-gurdy Nicholas Perry There will be one 20-minute intermission. Recorders, sackbut, shawms, tenor Claire McIntyre Viol, percussion David Hatcher Cal Performances’ 2009–2010 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. -

GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] +1(347)636.6681 AWARDS + HONORS SKILLS ASHLEY LAW EDUCATION WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL

ASHLEY LAW GRAPHIC DESIGNER [email protected] http://ashleylaw.info +1(347)636.6681 linkedin.com/in/ashley-law instagram.com/_ashleylaw EDUCATION AWA RDS SKILLS SCHOOL OF VISUAL + GRAPHIS (GOLD) SOFTWARE ARTS (New York) NEW TALENT ANNUAL InDesign HONORS BFA Design Editorial Design “Zine”- Illustrator 2017–2019 2018 Photoshop PremierePro AfterEffects SCHOOL OF THE SVA HONOR’S LIST Sketch ART INSTITUTE OF 2017–2018 CHICAGO (Chicago) Fine Art + Visual CAPABILITIES & Critical Studies SAIC MERIT Branding 2013–2015 SCHOLARSHIP Content Production 2013–2015 Identity System Interactive/Digital Design Print + Editorial Design Typography WORK EXPERIENCE UNIQLO GLOBAL Junior Graphic Design for the GCL team focusing on CREATIVE LAB Designer creative direction of special projects, 06. 2019 - Present (New York) under the direction of Shu Hung and John Jay. Campaigns include collaborations (i.e. Lemaire, JW Anderson, Alexander Wang) and new store openings. MATTE PROJECTS Design Intern Designing client proposals, print, 01. 2019–04. 2019 (New York) digital & social collateral for marketing agency. Worked on projects for Cartier, The Chainsmokers, Moda Operandi & MATTE events (FNT, BLACK-NYC, Full Moon Festival, La Luna). PYT OPERANDI Creative Project Associate for artist management & creative 03–06. 2016 Associate project development company with emphasis (Hong Kong) in film, photography, exhibitions, project & business development consulting. CLOVER GROUP Intimates Design Designed for leading global manufacturer INTL LIMITED. Intern of intimate apparel, emphasis on the 08–10. 2015 (Hong Kong) Victoria’s Secret account. Visually detailed creative direction, identity & design of project pitches. Similar work for clients including Wacoal, Aerie, Lane Bryant. GIORGIO ARMANI Menswear R&D Shadowed Manager of R&D department OPERATIONS Intern for Menswear at HK Armani Corporate 06–09. -

Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association

For internal use only Costume Design ©2019 Educational Theatre Association. All rights reserved. Student(s): School: Selection: Troupe: 4 | Superior 3 | Excellent 2 | Good 1 | Fair SKILLS Above standard At standard Near standard Aspiring to standard SCORE Job Understanding Articulates a broad Articulates an Articulates a partial Articulates little and Interview understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the understanding of the Articulation of the costume costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role costume designer’s role designer’s role and specific and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; and job responsibilities; job responsibilities; thoroughly presents adequately presents and inconsistently presents does not explain an presentation and and explains the explains the executed and explains the executed executed design, creative explanation of the executed executed design, creative design, creative decisions, design, creative decisions decisions or collaborative design, creative decisions, decisions, and and collaborative process. and/or collaborative process. and collaborative process. collaborative process. process. Comment: Design, Research, A well-conceived set of Costume designs, Incomplete costume The costume designs, and Analysis costume designs, research, and script designs, research, and research, and analysis Design, research and detailed research, and analysis address the script analysis of the script do not analysis addresses the thorough script artistic and practical somewhat address the address the artistic and artistic and practical needs analysis clearly address needs of the production artistic and practical practical needs of the (given circumstances) of the artistic and practical and support the unifying needs of the production production or support the the script to support the needs of production and concept. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

The Creative Application of Extended Techniques for Double Bass in Improvisation and Composition

The creative application of extended techniques for double bass in improvisation and composition Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Volume Number 1 of 2 Ashley John Long 2020 Contents List of musical examples iii List of tables and figures vi Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historical Precedents: Classical Virtuosi and the Viennese Bass 13 Chapter 2: Jazz Bass and the Development of Pizzicato i) Jazz 24 ii) Free improvisation 32 Chapter 3: Barry Guy i) Introduction 40 ii) Instrumental technique 45 iii) Musical choices 49 iv) Compositional technique 52 Chapter 4: Barry Guy: Bass Music i) Statements II – Introduction 58 ii) Statements II – Interpretation 60 iii) Statements II – A brief analysis 62 iv) Anna 81 v) Eos 96 Chapter 5: Bernard Rands: Memo I 105 i) Memo I/Statements II – Shared traits 110 ii) Shared techniques 112 iii) Shared notation of techniques 115 iv) Structure 116 v) Motivic similarities 118 vi) Wider concerns 122 i Chapter 6: Contextual Approaches to Performance and Composition within My Own Practice 130 Chapter 7: A Portfolio of Compositions: A Commentary 146 i) Ariel 147 ii) Courant 155 iii) Polynya 163 iv) Lento (i) 169 v) Lento (ii) 175 vi) Ontsindn 177 Conclusion 182 Bibliography 191 ii List of Examples Ex. 0.1 Polynya, Letter A, opening phrase 7 Ex. 1.1 Dragonetti, Twelve Waltzes No.1 (bb. 31–39) 19 Ex. 1.2 Bottesini, Concerto No.2 (bb. 1–8, 1st subject) 20 Ex.1.3 VerDi, Otello (Act 4 opening, double bass) 20 Ex.