Lecture Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WARM WARM Kerning by Eye for Perfectly Balanced Spacing

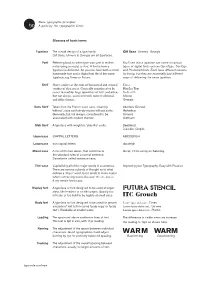

Basic typographic principles: A guide by The Typographic Circle Glossary of basic terms Typeface The overall design of a type family Gill Sans Univers Georgia Gill Sans, Univers & Georgia are all typefaces. Font Referring back to when type was cast in molten You’ll see that a typeface can come in various metal using a mould, or font. A font is how a types of digital font; such as OpenType, TrueType typeface is delivered. So you can have both a metal and Postscript fonts. Each have different reasons handmade font and a digital font file of the same for being, but they are essentially just different typeface, e.g Times or Futura. ways of delivering the same typeface. Serif Short strokes at the ends of horizontal and vertical Times strokes of characters. Generally considered to be Hoefler Text easier to read for large quantities of text, and often, Baskerville but not always, associated with more traditional Minion and older themes. Georgia Sans Serif Taken from the French word sans, meaning Akzidenz Grotesk ‘without’, sans serif simply means without serifs. Helvetica Generally, but not always, considered to be Univers associated with modern themes. Gotham Slab Serif A typeface with weightier, ‘slab-like’ serifs. Rockwell Lubalin Graph Uppercase CAPITAL LETTERS ABCDEFGH Lowercase non-capital letters abcdefgh Mixed-case A mix of the two above, that conforms to Great, it’ll be sunny on Saturday. the standard rules of a normal sentence. Sometimes called sentence-case. Title-case Capitalising all of the major words in a sentence. Improving your Typography: Easy with Practice There are various schools of thought as to what defines a ‘major’ word, but it tends to looks neater when connecting words like and, the, to, but, is & my remain lowercase. -

Film Essay for "Mccabe & Mrs. Miller"

McCabe & Mrs. Miller By Chelsea Wessels In a 1971 interview, Robert Altman describes the story of “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” as “the most ordinary common western that’s ever been told. It’s eve- ry event, every character, every west- ern you’ve ever seen.”1 And yet, the resulting film is no ordinary western: from its Pacific Northwest setting to characters like “Pudgy” McCabe (played by Warren Beatty), the gun- fighter and gambler turned business- man who isn’t particularly skilled at any of his occupations. In “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Altman’s impressionistic style revises western events and char- acters in such a way that the film re- flects on history, industry, and genre from an entirely new perspective. Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie) and saloon owner McCabe (Warren Beatty) swap ideas for striking it rich. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. The opening of the film sets the tone for this revision: Leonard Cohen sings mournfully as the when a mining company offers to buy him out and camera tracks across a wooded landscape to a lone Mrs. Miller is ultimately a captive to his choices, una- rider, hunched against the misty rain. As the unidenti- ble (and perhaps unwilling) to save McCabe from his fied rider arrives at the settlement of Presbyterian own insecurities and herself from her opium addic- Church (not much more than a few shacks and an tion. The nuances of these characters, and the per- unfinished church), the trees practically suffocate the formances by Beatty and Julie Christie, build greater frame and close off the landscape. -

The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick the Philosophy of Popular Culture

THE PHILOSOPHY OF STANLEY KUBRICK The Philosophy of Popular Culture The books published in the Philosophy of Popular Culture series will illuminate and explore philosophical themes and ideas that occur in popular culture. The goal of this series is to demonstrate how philosophical inquiry has been reinvigo- rated by increased scholarly interest in the intersection of popular culture and philosophy, as well as to explore through philosophical analysis beloved modes of entertainment, such as movies, TV shows, and music. Philosophical con- cepts will be made accessible to the general reader through examples in popular culture. This series seeks to publish both established and emerging scholars who will engage a major area of popular culture for philosophical interpretation and examine the philosophical underpinnings of its themes. Eschewing ephemeral trends of philosophical and cultural theory, authors will establish and elaborate on connections between traditional philosophical ideas from important thinkers and the ever-expanding world of popular culture. Series Editor Mark T. Conard, Marymount Manhattan College, NY Books in the Series The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick, edited by Jerold J. Abrams The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese, edited by Mark T. Conard The Philosophy of Neo-Noir, edited by Mark T. Conard Basketball and Philosophy, edited by Jerry L. Walls and Gregory Bassham THE PHILOSOPHY OF StaNLEY KUBRICK Edited by Jerold J. Abrams THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. -

HJR 23.1 Sadoff

38 The Henry James Review Appeals to Incalculability: Sex, Costume Drama, and The Golden Bowl By Dianne F. Sadoff, Miami University Sex is the last taboo in film. —Catherine Breillat Today’s “meat movie” is tomorrow’s blockbuster. —Carol J. Clover When it was released in May 2001, James Ivory’s film of Henry James’s final masterpiece, The Golden Bowl, received decidedly mixed reviews. Kevin Thomas calls it a “triumph”; Stephen Holden, “handsome, faithful, and intelligent” yet “emotionally distanced.” Given the successful—if not blockbuster—run of 1990s James movies—Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady (1996), Agniezka Holland’s Washington Square (1997), and Iain Softley’s The Wings of the Dove (1997)—the reviewers, as well as the fans, must have anticipated praising The Golden Bowl. Yet the film opened in “selected cities,” as the New York Times movie ads noted; after New York and Los Angeles, it showed in university towns and large urban areas but not “at a theater near you” or at “theaters everywhere.” Never mind, however, for the Merchant Ivory film never intended to be popular with the masses. Seeking a middlebrow audience of upper-middle-class spectators and generally intelligent filmgoers, The Golden Bowl aimed to portray an English cultural heritage attractive to Anglo-bibliophiles. James’s faux British novel, however, is paradoxically peopled with foreigners: American upwardly mobile usurpers, an impoverished Italian prince, and a social-climbing but shabby ex- New York yentl. Yet James’s ironic portrait of this expatriate culture, whose characters seek only to imitate their Brit betters—if not in terms of wealth and luxury, at least in social charm and importance—failed to seem relevant to viewers The Henry James Review 23 (2002): 38–52. -

Widescreen Weekend 2010 Brochure (PDF)

52 widescreen weekend widescreen weekend 53 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (70MM) REMASTERING A WIDESCREEN CLASSIC: Saturday 27 March, Pictureville Cinema WINDJAMMER GETS A MAJOR FACELIFT Dir. Stanley Kubrick GB/USA 1968 149 mins plus intermission (U) Saturday 27 March, Pictureville Cinema WIDESCREEN Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Leonard Rossiter, Ed Presented by David Strohmaier and Randy Gitsch Bishop and Douglas Rain as Hal The producer and director team behind Cinerama Adventure offer WEEKEND During the stone age, a mysterious black monolith of alien origination a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how the Cinemiracle epic, influences the birth of intelligence amongst mankind. Thousands Now in its 17th year, the Widescreen Weekend Windjammer, was restored for High Definition. Several new and of years later scientists discover the monolith hidden on the moon continues to welcome all those fans of large format and innovative software restoration techniques were employed and the re- which subsequently lures them on a dangerous mission to Mars... widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, mastering and preservation process has been documented in HD video. Regarded as one of the milestones in science-fiction filmmaking, Cinerama and IMAX – and presents an array of past A brief question and answer session will follow this event. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey not only fascinated audiences classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. This event is enerously sponsored by Cinerama, Inc., all around the world but also left many puzzled during its initial A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. release. More than four decades later it has lost none of its impact. -

Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of Film and Television

Essais Revue interdisciplinaire d’Humanités Hors-série 4 | 2018 Stanley Kubrick Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of film and television Matthew Melia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/essais/646 DOI: 10.4000/essais.646 ISSN: 2276-0970 Publisher École doctorale Montaigne Humanités Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2018 Number of pages: 195-219 ISBN: 979-10-97024-04-8 ISSN: 2417-4211 Electronic reference Matthew Melia, « Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of film and television », Essais [Online], Hors-série 4 | 2018, Online since 01 December 2019, connection on 16 December 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/essais/646 ; DOI : 10.4000/essais.646 Essais Stanley Kubrick at the Interface of film and television Matthew Melia During his keynote address at the 2016 conference Stanley Kubrick: A Retrospective1 Jan Harlan2 announced that Napoleon, Kubrick’s great unrea- lised project3 would finally be produced, as a HBO TV mini-series, directed by Cary Fukunaga (True Detective, HBO) and executively produced by Steven Spielberg. He also suggested that had Kubrick survived into the 21st century he would not only have chosen TV as a medium to work in, he would also have contributed to the contemporary post-millennium zeitgeist of cinematic TV drama. There has been little news on the development of the project since and we are left to speculate how this cinematic spectacle eventually may (or may not) turn out on the “small screen”. Alison Castle’s monolithic edited collection of research and production material surrounding Napoleon4 gives some idea of the scale, ambition and problematic nature of re-purposing such a momen- tous project for television. -

Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur Adriana Magda College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 15 Article 24 Spring 2017 Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur Adriana Magda College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Magda, Adriana (2017) "Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur," ESSAI: Vol. 15 , Article 24. Available at: https://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol15/iss1/24 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Magda: Stanley Kubrick -- Auteur Stanley Kubrick – Auteur by Adriana Magda (Motion Picture Television 1113) tanley Kubrick is considered one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers in history. Many important directors credit Kubrick as an important influence in their career and Sinspiration for their vision as filmmaker. Kubrick’s artistry and cinematographic achievements are undeniable, his body of work being a must watch for anybody who loves and is interested in the art of film. However what piqued my interest even more was finding out about his origins, as “Kubrick’s paternal grandmother had come from Romania and his paternal grandfather from the old Austro-Hungarian Empire” (Walker, Taylor, & Ruchti, 1999). Stanley Kubrick was born on July 26th 1928 in New York City to Jaques Kubrick, a doctor, and Sadie Kubrick. He grew up in the Bronx, New York, together with his younger sister, Barbara. Kubrick never did well in school, “seeking creative endeavors rather than to focus on his academic status” (Biography.com, 2014). While formal education didn’t seem to interest him, his two passions – chess and photography – were key in shaping the way his mind worked. -

Bulworth: the Hip-Hop Nation Confronts Corporate Capitalism a Review Essay

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 8 (1998) : 73-80. Bulworth: The Hip-Hop Nation Confronts Corporate Capitalism A Review Essay James Allen and Lawrence Goodheart Co-written, directed by, and starring Warren Beatty, Bulworth (1998) is a scathing political satire that ranks with Stanley Kubrick’s Doctor Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1963). While Kubrick skewered assumptions about nuclear strategy at the height of the Cold War, Beatty indicts the current corporate manipulation of American politics. Bulworth challenges the reigning capitalist mystique through a tragi- comedy that blends manifesto with farce and the serious with slapstick, in a format that is as enlightening as it is entertaining. The film is a mix of genres and stereotypes, common to mass-marketed movies, that Beatty nonetheless recasts into a radical message. He calls for democratic socialism and heralds the black urban underclass as its vanguard in a manner reminiscent of Herbert Marcuse’s formulation of a generation ago. The opening scene of Bulworth establishes what Beatty sees as the fundamental malaise of American politics today—that the rich rule the republic. The eponymous protagonist, Senator Jay Billington Bulworth, played by Beatty himself, is the case in point. The incumbent Democratic senator from California has cynically abandoned his former liberal principals in the wake of the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s that marked the demise of the New Deal legacy. Even his pompous three-part name suggests not only a prominent pedigree but also a pandering politician, one full of “bull.” During the last days of the 1996 primary campaign, Bulworth suffers a crisis of faith in his bid for renomination. -

Guido Götz / MPRM 323-933-3399 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Guido Götz / MPRM 323-933-3399 [email protected] BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS LOS ANGELES (BAFTA LOS ANGELES) TO HONOR HELENA BONHAM CARTER 20TH ANNUAL 2011 BAFTA LOS ANGELES BRITANNIA AWARDS November 30, 2011 Los Angeles, July 13, 2011 -- The British Academy of Film and Television Arts Los Angeles® (BAFTA Los Angeles) will honor Academy Award® nominated and BAFTA winning actress Helena Bonham Carter with the Britannia Award for British Artist of the Year at the 2011 BAFTA Los Angeles Britannia Awards on Wednesday, November 30 at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The Britannia Awards are BAFTA Los Angeles’ highest accolade, a celebration of achievements honoring individuals and companies that have dedicated their careers or corporate missions to advancing the entertainment arts. “Helena Bonham Carter is an actress of immense versatility, and her range across movies of all genres is at once remarkable and fearless,” says Nigel Lythgoe, Chairman of BAFTA Los Angeles. “She unwaveringly maintains her integrity and, through her choice of roles, continually challenges both herself and her audiences' perception of her.” Bonham Carter joins the previously announced John Lasseter who will receive the Britannia Award for Worldwide Contribution to Filmed Entertainment, and David Yates who will be honored with the John Schlesinger Britannia Award for Excellence in Directing. Additional awards which are presented at the annual Britannia evening include the Stanley Kubrick Britannia Award for Excellence in Film and the Charlie Chaplin Award for Excellence in Comedy. The Britannia Awards are presented annually at a gala dinner, where peers and colleagues celebrate the work and accomplishments of the distinguished honorees. -

Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

Press Release Berlinale 2017: An Honorary Golden Bear and Homage for Oscar- winner Milena Canonero The Homage of the 67th Berlin International Film Festival is dedicated to Italian costume designer Milena Canonero, who will also receive an Honorary Golden Bear for her lifetime achievement. Milena Canonero is one of the world’s most celebrated costume designers. She has worked with a long list of directors, including Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, Sydney Pollack, Warren Beatty, Roman 67. Internationale Filmfestspiele Polanski, Steven Soderbergh, Louis Malle, Tony Scott, Barbet Schroeder, Berlin Sofia Coppola, and Wes Anderson. Over the years she has won four 09. – 19.02.2017 Academy Awards for her outstanding costume designs and been nominated five other times. Presse Potsdamer Straße 5 “Milena Canonero is an extraordinary costume designer. With her designs 10785 Berlin she has contributed decisively to the style of many cinematic masterpieces. With this year’s Homage, we would like to honour a great Phone +49 · 30 · 259 20 · 707 artist as well as direct attention to another film profession,” says Fax +49 · 30 · 259 20 · 799 Berlinale Director Dieter Kosslick. [email protected] www.berlinale.de Milena Canonero’s designs result from extensive art historical research and sophisticated concepts. She never just adopts parameters from fashion history but adapts them creatively for each movie. In doing so she excels not only in the art of subtly accentuating a character’s personality but also in enhancing the texture of a film through very detailed and original designs. Her creations have influenced global fashion trends and inspired fashion designers such as Alexander McQueen and Ralph Lauren. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Space Architecture in Film Environ- Ments: an Opportunity Lost

108 SEEKING THE CITY Defying Gravity: Space Architecture in Film Environ- ments: An Opportunity Lost TERRI MEYER BOAKE University of Waterloo INTRODUCTION Unlike architecture, fi lm spaces have never had to be realistic, nor have they been obliged to possess Film gives us the rare opportunity to completely a conscience. That is not to say, however, that question all that has come to be accepted in terms the notions of science or conscience have failed to of the language of architecture as well as cultural be vital motivations behind the creation of many and historic convention. It allows for educated fi lms. Film producers and directors though, can speculation on what may have been in the past, make a conscious decision whether to choose to and what the world of the future might become. respect scientifi c accuracy, and how to portray Current fi lm technologies provide such a high de- moral and political conscience. An examination of gree of realism in the product, that architectural scientifi c timelines can begin to allow us to un- education can use these fi lms as vehicles for criti- derstand the development of the space genre of cal discussion of the ethos of these environments. fi lm as it relates to accurate scientifi c invention.1 Much like, and yet experientially speaking, well If scientifi c knowledge was available at the time of beyond the efforts of the Visionary architects of the writing of books and making of fi lms, it will be the 18th century, fi lm can create speculations of assumed that such was purposefully ignored, for realistic feeling environments that can be used to either artistic or technological cause, if not shown reinvent the meaning and defi ning factors of ar- to be respected.