Fallon Fox: a Queer Body in the Octagon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

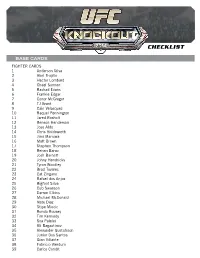

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

The Week Ahead

THE WEEK AHEAD Week of May 11, 2013 – May 17, 2013 Asian Pacific American Heritage Month takes place May 1 – May 30 Saturday, May 11 - The Board of School Trustees seeks the public's input on the superintendent selection process, as well as the direction the district is taking and the reforms under way. Please participate in the online survey at http://ccsd.net/district/superintendent-selection-process/ and join the trustees for a town hall meeting at Western High School’s theater, 4601 W. Bonanza Rd., Las Vegas, at 9:30 a.m. Monday, May 13 - The Board of School Trustees seeks the public's input on the superintendent selection process, as well as the direction the district is taking and the reforms under way. Please participate in the online survey at http://ccsd.net/district/superintendent-selection-process/ and join the trustees for a town hall meeting at Legacy High School’s theater, 150 W. Deer Springs Way, Las Vegas, at 7 p.m. Tuesday, May 14 - Scooter Christensen of the Harlem Globetrotters will visit with students of John Bonner Elementary School at 9:30 a.m. He will talk about S.P.I.N. (Some Playtime Is Necessary), a program designed to make fitness fun for children, while promoting and encouraging an active lifestyle. Christensen lists Las Vegas as his hometown. Bonner Elementary School is located at 765 Crestdale Ln., Las Vegas. For more information, call Ruby Ramirez of the Harlem Globetrotters at (602) 707-7022. Tuesday, May 14 - Jack Lund Schofield Middle School and the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), will be hosting an anti-bullying program, geared toward sixth and seventh grade students, from 8 - 10:30 a.m. -

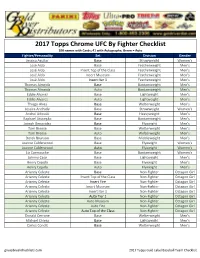

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

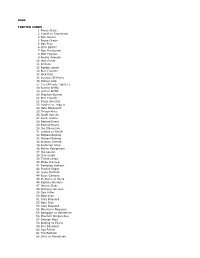

1 Robbie Lawler 2 Conor Mcgregor 3 Paige Vanzant

BASE CARDS 1 Robbie Lawler 2 Conor McGregor 3 Paige VanZant 4 Georges St-Pierre 5 Anderson Silva 6 Ronda Rousey 7 Daniel Cormier 8 Matt HugHes 9 Fabricio Werdum 10 Chuck Liddell 11 Forrest Griffin 12 Lyoto MacHida 13 BJ Penn 14 TJ DillasHaw 15 Frank Mir 16 MiesHa Tate 17 Frankie Edgar 18 Cris Justino 19 Arianny Celeste 20 José Aldo 21 RasHad Evans 22 Rafael Dos Anjos 23 CM Punk 24 Joanna Jędrzejczyk 25 Dominick Cruz 26 Demetrious JoHnson 27 Stipe Miocic 28 Cláudia GadelHa 29 Tyron Woodley 30 StepHen Thompson 31 MicHelle Waterson 32 Joanne Calderwood 34 Luke RockHold 35 Antonio Silva 36 Nate Diaz 37 Henry Cejudo 38 Cody Garbrandt 39 JosepH Benavidez 40 Amanda Nunes 41 Anthony JoHnson 42 Junior Dos Santos 43 Donald Cerrone 44 Eddie Alvarez 45 KHabib Nurmagomedov 46 Holly Holm 47 Carlos Condit 49 Rose Namajunas 50 Cat Zingano 51 Yoel Romero 52 Jim Miller 53 Neil Magny 54 Glover Teixeira 55 Al Iaquinta 56 Jessica Aguilar 57 Joe Lauzon 58 Nick Diaz 59 JoHn Dodson 60 Ovince Saint Preux 61 Andrew SancHez 62 Robert WHittaker 63 Randa Markos 64 Julianna Peña 65 THiago Alves 67 Tecia Torres 68 JoHnny Case 69 Ryan Hall 70 Raquel Pennington 71 Mickey Gall 72 Jimmie Rivera 73 THomas Almeida 74 Sage Northcutt 75 Valentina Shevchenko 76 Karolina Kowalkiewicz 77 Jessica Andrade 78 CHas Skelly 79 Derek Brunson 80 Andrei Arlovski 81 JoHny Hendricks 82 MicHael Chiesa 83 Dustin Poirier 84 James Vick 85 Jessica Eye 86 Louis Smolka 87 Sara McMann 88 Alexa Grasso 89 Liz CarmoucHe 90 Demian Maia 91 Tony Ferguson 92 Cub Swanson 93 Max Holloway 94 JoHn Lineker -

Ufc® Announces That Lyoto Machida Will Fight Champion Chris Weidman at Ufc 173

UFC® ANNOUNCES THAT LYOTO MACHIDA WILL FIGHT CHAMPION CHRIS WEIDMAN AT UFC 173 Las Vegas, Nev. – The Ultimate Fighting Championship® announced tonight that former UFC light heavyweight champion Lyoto “The Dragon” Machida will face off against UFC middleweight champion Chris Weidman in the main event of UFC 173 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas on Saturday, May 24. In light of today’s unexpected ruling issued by the Nevada State Athletic Commission regarding the ban of therapeutic use exemptions for testosterone replacement therapy, Vitor Belfort, Weidman’s previously announced opponent, will no longer compete at UFC 173. Belfort, who has previously been granted therapeutic use exemptions, recognizes that he needs an extended period of time to become licensed in the state of Nevada. With the event scheduled to go on sale shortly, Belfort agreed to withdraw from the fight in order to allow the UFC’s promotional efforts to move forward on time. “With today’s ruling by the Nevada State Athletic Commission, former UFC light heavyweight champion Lyoto Machida, who’s undefeated since dropping to 185 pounds, will fight champion Chris Weidman in the main event of UFC 173 in May,” UFC President Dana White said. “Machida was dominant in his last two fights, beating Gegard Mousasi and knocking out Mark Munoz. He’s earned this shot at Weidman, who’s coming off two straight wins over the greatest fighter of all time, Anderson Silva. Machida wants nothing more than to avenge the losses of his friend and training partner, and become just the third fighter in UFC history to win titles in two separate weight classes.” For more information or current fight news, visit www.ufc.com. -

Fox Sports Highlights – 3 Things You Need to Know

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014 FOX SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW NFL: Philadelphia Hosts Washington and Dallas Meets St. Louis in Regionalized Matchups COLLEGE FOOTBALL: No. 4 Oklahoma Faces West Virginia in Big 12 Showdown on FOX MLB: AL Central Battle Between Tigers and Royals, Plus Dodgers vs. Cubs in FOX Saturday Baseball ******************************************************************************************************* NFL DIVISIONAL MATCHUPS HIGHLIGHT WEEK 3 OF THE NFL ON FOX The NFL on FOX continues this week with five regionalized matchups across the country, highlighted by three divisional matchups, as the Philadelphia Eagles host the Washington Redskins, the Detroit Lions welcome the Green Bay Packers, and the San Francisco 49ers play at the Arizona Cardinals. Other action this week includes the Dallas Cowboys at St. Louis Rams and Minnesota Vikings at New Orleans Saints. FOX Sports’ NFL coverage begins each Sunday on FOX Sports 1 with FOX NFL KICKOFF at 11:00 AM ET with host Joel Klatt and analysts Donovan McNabb and Randy Moss. On the FOX broadcast network, FOX NFL SUNDAY immediately follows FOX NFL KICKOFF at 12:00 PM ET with co-hosts Terry Bradshaw and Curt Menefee alongside analysts Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Jimmy Johnson, insider Jay Glazer and rules analyst Mike Pereira. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 GAME PLAY-BY-PLAY/ANALYST/SIDELINE COV. TIME (ET) Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles Joe Buck, Troy Aikman 24% 1:00PM & Erin Andrews Lincoln Financial Field – Philadelphia, Pa. MARKETS INCLUDE: Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, Raleigh, Charlotte, Hartford, Greenville, West Palm Beach, Norfolk, Greensboro, Richmond, Knoxville Green Bay Packers at Detroit Lions Kevin Burkhardt, John Lynch 22% 1:00PM & Pam Oliver Ford Field – Detroit, Mich. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

Ufc Welterweight Champion Tyron Woodley, Former

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: John Stouffer Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2017 [email protected] UFC WELTERWEIGHT CHAMPION TYRON WOODLEY, FORMER MIDDLEWEIGHT CHAMPION CHRIS WEIDMAN JOIN AS FOX SPORTS DESK ANALYSTS WITH KENNY FLORIAN & HOST KARYN BRYANT FOR UFC 217: BISPING VS. GSP UFC Light Heavyweight Champion Daniel Cormier Calls Fights with Analyst Joe Rogan and Blow-by-Blow Announcer Jon Anik UFC TONIGHT, UFC 217 FIGHT NIGHT PREFIGHT and POSTFIGHT SHOWS Live From New York City Los Angeles – Today, FOX Sports announces its broadcast team for UFC 217: BISPING VS. GSP on FS1 and FOX Deportes this Friday and Saturday. Current UFC welterweight champion Tyron Woodley (@TWooodley), former middleweight champion Chris Weidman (@ChrisWeidmanUFC) and retired contender Kenny Florian (@KennyFlorian) serve as FOX Sports desk analysts with host Karyn Bryant (@KarynBryant) live from New York City. UFC light heavyweight champion Daniel Cormier (@dc_mma) joins analyst Joe Rogan (@JoeRogan) and blow-by-blow announcer Jon Anik (@Jon_Anik) to call UFC 217: BISPING VS. GSP on Saturday live from Madison Square Garden. Reporter Megan Olivi (@MeganOlivi) interviews fighters on-site. UFC bantamweight Erik “Goyito” Perez (@Goyito_Perez), Santiago Ponzinibbio (@SPonzinibbioMMA) and Victor Davila (@mastervic10) call the Spanish language telecast on FOX Deportes. In the UFC 217 main event, middleweight champion Michael Bisping (31-7) faces returning Canadian legend Georges St-Pierre (25-2). After a career-best year in 2016, in which he beat superstars Anderson Silva and Dan Henderson and scored a knockout of Luke Rockhold that earned him the UFC middleweight crown, Bisping attempts to add another superstar, St-Pierre, to his resume. -

25 Pro Fighters, Managers, and Coaches Reveal Their Best Tips to Land a Sponsorship by Solmadrid Vazquez Follow Me on Twitter Here

25 Pro Fighters, Managers, and Coaches Reveal Their Best Tips to Land a Sponsorship by Solmadrid Vazquez Follow me on Twitter here. Sponsorships can make or break you. The problem is, the process of landing a sponsorship is counter-intuitive. Being a great fighter is NOT enough. I’m sure you’ve seen fighters who land sponsors left and right. What’s their secret? How come they can get 27 sponsors in one day and you can’t even get one freakin’ rep to look at you? What THE hell is going on?! To get to this bottom of this conundrum, I contacted some of the best fighters, managers, and trainers in the game and asked them a simple question: “What is your #1 tip to land a sponsorship?” Each tip has a custom tweet link after it so feel free to share your favorite tips with your followers. Let’s Get Ready To Ruuuummmmbllllllleee!!! Frank Shamrock Frank Shamrock is a retired MMA Fighter. He was the first UFC Middleweight Champion and retired as the four-time defending undefeated champion. He was also the first WEC Light Heavyweight Champion, and the first Strikeforce Middleweight Champion. He was a brand spokesman for Strikeforce and is a Sports Commentator for Showtime. Frank can be found at his site, on Facebook, and on Twitter. My number one tip to landing a sponsorship is presenting yourself properly. Present a long-term consistent growth plan that somebody, or a sponsor, could attach themselves to, so you can show how you will grow together. “Present a long-term consistent growth plan.” Tweet this. -

Undefeated Olympians Collide As Champion Ronda Rousey Meets Sara Mcmann at Ufc® 170 Saturday, February 22

UNDEFEATED OLYMPIANS COLLIDE AS CHAMPION RONDA ROUSEY MEETS SARA MCMANN AT UFC® 170 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 22 Las Vegas, Nevada – In what could prove to be her toughest challenge yet, UFC® women’s bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey (8-0, fighting out of Venice, Calif.) squares off against undefeated wrestling sensation Sara McMann (7-0, fighting out of Gaffney, SC) in a battle of Olympic medalists at UFC® 170 at the Mandalay Bay Events Center Saturday, Feb. 22. A bronze medal winner in Judo at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, Rousey recently defeated her bitter rival Miesha Tate at UFC 168 to retain the women’s bantamweight belt and remain the divison’s only champion. Now she takes on McMann, who comes in as the most decorated wrestler in the weight class, having also earned Olympic silver at the 2004 games in Athens in free- style wrestling. In addition to the Rousey-McMann tilt, (No. 3) Rashad Evans (19-3, fighting out of Boca Raton, Fla.), a former light heavyweight champion, battles the Strikeforce Heavyweight Grand Prix winner Daniel Cormier (13-0, fighting out of San Jose, Calif.) in his debut at the 205-pound weight class. Evans comes into the bout sporting consecutive wins over Dan Henderson and Chael Sonnen while Cormier is looking to keep his unblemished professional record and make a statement in his new division. The card also features Brazilian jiu-jitsu ace (No. 6) Demian Maia (18-5, fighting out of Sao Paulo, Brazil) matching up against Canadian prodigy and Georges-St. Pierre training partner (no. 4) Rory MacDonald (15-2, fighting out of Montreal, Canada) in a battle of Top 10-ranked welterweights. -

2006-07 HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY WRESTLING SCHEDULE As of March 2, 2007 ± 18-4-2, 7-0

2007 CAA Wrestling Championships Schedule Friday, March 2 1 p.m. – First round 4 p.m. – Quarterfinals 8 p.m. – First round consolations Saturday, March 3 10 a.m. – Second round consolations Noon – Semifinals 2 p.m. – Third round consolations 2006-07 HOFSTRA 4 p.m. – Consolation finals 6 p.m. - Finals UNIVERSITY WRESTLING After finals, true second place matches #9 Hofstra Pride (18-4-2) HOFSTRA THIS YEAR: The Pride will be going after their at sixth consecutive Colonial Athletic Association Wrestling title Colonial Athletic Association Championships and their seventh straight conference title (2001 in the ECWA) Linn Gymnasium - George Mason University this weekend at the 2007 CAA Wrestling Championships at Friday-Saturday, March 2-3, 2007 - Fairfax, VA George Mason University. Hofstra, which is coming off a 21-13 loss at #15 Oklahoma on February 17 in Norman, OK, was 18- 4-2 in dual matches this year. The Pride concluded another 2006-07 HOFSTRA perfect conference regular season with a 29-9 victory over Colonial Athletic Association preseason favorite Rider on WRESTLING SCHEDULE/RESULTS February 13. Prior to the Rider match, the Pride dropped a 22-18 Nov. 14 at Wagner * 56-0 W decision to Cornell, snapping a seven-match winning streak. Nov. 15 ARMY 41-0 W Hofstra recorded a 31-3 victory over #14 Penn and a 30-6 Nov. 18 at East Stroudsburg Open All Day victory over #24 Lehigh. Hofstra recorded a 5-0 mark on Nov. 25 at Journeymen/Brute Northeast Duals January 19-20 at the Colonial Athletic Association Duals at vs.