Apple Has Fallen from the Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Survey, Which Measured the Status of Computer Community for Use

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 234 764 IR 010 831 TITLE The US6 of the Computer in Louisiana Schools. Bulletin 1679. Revised. INSTITUTION Louisiana Sta'te Dept. of Education, Baton Rouge. PUB DATE Apr 83 NOTE 70p. PUB TYPE Statistical Data (110) --- Reports Research/Technical (143) -- Teits/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer Assisted Instruction; *Computers; Elementary Secondary Education;_Information Networks; *Private Schools; *Public Schools; State Surveys; Technology Traii-gfer *USe Studies IDENTIFIERS Computer Uses in Education; *LouiSiana ABSTRACT This- publication briefly reports the findings of a second annual (1982=83) survey, which measured the status of computer use to identify problemt and needs_in the Louisiana educational community for use by the Department of Education in designing activities to Aid the state's schools in effective computer use. Data are_included from a survey instrument which was returned by 1,079 public' And nonpublic Louisiana schools. Currently 345 of.the responding Schools are using computers in instruction. A summaryof findings, which includes seven data tables, is followed by conclusions and recommendations. The major part of_the report comprises appeddices that are designed to enable educators to Iodate . schools using similar computers in similar areas in order to share ideas, educational software, and hardware information.. Included are the survey instrument and an indication of,the grade levelsand subject areas in which schools reported using computers, a list showing the make and model of computer used listed byschOol, and a list by computer make of the schools using specific cotputers. (LMM) *****************************************************************t***** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

Take Control of Podcasting on the Mac (3.1) SAMPLE

EBOOK EXTRAS: v3.1 Downloads, Updates, Feedback TAKE CONTROL OF PODCASTING ON THE MAC by ANDY AFFLECK $15 3RD Click here to buy “Take Control of Podcasting on the Mac” for only $15! EDITION Table of Contents Read Me First ............................................................... 4 Updates and More ............................................................. 4 Basics .............................................................................. 5 What’s New in Version 3.1 .................................................. 5 What Was New in Version 3.0 ............................................. 6 Introduction ................................................................ 7 Podcasting Quick Start ................................................ 9 Plan Your Podcast ...................................................... 10 Decide What You Want to Say ........................................... 10 Pick a Format .................................................................. 10 Listen to Your Audience, Listen to Your Show ....................... 11 Learn Podcasting Terminology ........................................... 11 Consider Common Techniques ........................................... 13 Set Up Your Studio .................................................... 15 Choose a Mic and Supporting Hardware .............................. 15 Choose Audio Software .................................................... 33 Record Your Podcast .................................................. 42 Use Good Microphone Techniques ..................................... -

Avtal För Apple Business Manager

LÄS NOGGRANT IGENOM FÖLJANDE VILLKOR FÖR APPLE BUSINESS MANAGER INNAN DU ANVÄNDER TJÄNSTEN. DESSA VILLKOR UTGÖR ETT JURIDISKT BINDANDE AVTAL MELLAN INSTITUTIONEN OCH APPLE. GENOM ATT KLICKA PÅ KNAPPEN ”GODKÄNN” SAMTYCKER INSTITUTIONEN, VIA SITT AUKTORISERADE OMBUD, TILL ATT INGÅ DETTA AVTAL OCH VARA BUNDEN TILL DESS VILLKOR. OM INSTITUTIONEN INTE SAMTYCKER TILL ELLER INTE KAN GODKÄNNA DETTA AVTAL SKA OMBUDET KLICKA PÅ KNAPPEN ”AVBRYT”. OM INSTITUTIONEN INTE SAMTYCKER TILL DETTA AVTAL ÄR INSTITUTIONEN INTE TILLÅTEN ATT DELTA. Avtal för Apple Business Manager Syfte Detta Avtal tillåter att Du deltar i Apple Business Manager, vilket tillåter Dig att automatisera registreringen av Apple-märkta produkter för MDM (Mobile Device Management) på Din Institution samt att köpa och hantera innehåll för sådana enheter, skapa hanterade Apple-ID:n för Dina användare och få åtkomst till verktyg som underlättar driftsättningen av de relaterade tjänsterna. Obs! Du måste ha en MDM-lösning (till exempel Profile Manager från macOS Server, eller från en tredjepartsutvecklare) i drift på Din Institution för att kunna nyttja funktionerna i denna Tjänst. Med en MDM-lösning kan Du konfigurera, driftsätta och hantera Apple-märkta enheter. Mer information finns i https://www.apple.com/business/resources/. 1. Definitioner När ordet inleds med stor bokstav i detta Avtal: ”Administratörer” avser medarbetare eller Kontraktsmedarbetare (eller Tjänsteleverantörer) hos Institutionen som har lagts till i Tjänsten för syften som rör kontohantering, till exempel serveradministrering, -

Distributed Tuning of Boundary Resources: the Case of Apple's Ios Service System

Ben Eaton, Silvia Elaluf-Calderwood, Carsten Sørensen and Youngjin Yoo Distributed tuning of boundary resources: the case of Apple's iOS service system Article (Published version) (Refereed) Original citation: Eaton, Ben, Elaluf-Calderwood, Silvia, Sorensen, Carsten and Yoo, Youngjin (2015) Distributed tuning of boundary resources: the case of Apple's iOS service system. MIS Quarterly, 39 (1). pp. 217-243. ISSN 0276-7783 Reuse of this item is permitted through licensing under the Creative Commons: © 2015 The Authors CC-BY This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63272/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. SPECIAL ISSUE: SERVICE INNOVATION IN THE DIGITAL AGE DISTRIBUTED TUNING OF BOUNDARY RESOURCES: THE CASE OF APPLE’S IOS SERVICE SYSTEM1 Ben Eaton Department of IT Management, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, DENMARK {[email protected]} Silvia Elaluf-Calderwood and Carsten Sørensen Department of Management, The London School of Economics and Political Science, London, GREAT BRITAIN {[email protected]} {[email protected]} Youngjin Yoo Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19140 UNITED STATES {[email protected]} The digital age has seen the rise of service systems involving highly distributed, heterogeneous, and resource- integrating actors whose relationships are governed by shared institutional logics, standards, and digital technology. -

Apple Products' Impact on Society

Apple Products’ Impact on Society Tasnim Eboo IT 103, Section 003 October 5, 2010 Honor Code: "By placing this statement on my webpage, I certify that I have read and understand the GMU Honor Code on http://academicintegrity.gmu.edu/honorcode/ . I am fully aware of the following sections of the Honor Code: Extent of the Honor Code, Responsibility of the Student and Penalty. In addition, I have received permission from the copyright holder for any copyrighted material that is displayed on my site. This includes quoting extensive amounts of text, any material copied directly from a web page and graphics/pictures that are copyrighted. This project or subject material has not been used in another class by me or any other student. Finally, I certify that this site is not for commercial purposes, which is a violation of the George Mason Responsible Use of Computing (RUC) Policy posted on http://universitypolicy.gmu.edu/1301gen.html web site." Introduction Apple was established in 1976 and has continuously since that date had an impact on our society today. Apple‟s products have grown year after year, with new inventions and additions to products coming out everyday. People have grown to not only recognize these advance items by their aesthetic appeal, but also by their easy to use methodology that has created a new phenomenon that almost everyone in the world knows about. With Apple‟s worldwide annual sales of $42.91 billion a year, one could say that they have most definitely succeeded at their task of selling these products to the majority of people. -

Iphone Privacy

Security & Risk Conference November 3th - 6th 2010 Lucerne, Switzerland Apple iOS Privacy Nicolas Seriot Twitter @nst021 Malware on Mobile Phones • Was a fantasy two years ago • Is now something common • Many fantasy among consumers • “Can my iPhone spy on me?” Reach Consumer Phones • Unix permissions + sandbox • Autoregulated market • Spywares, fake banking applications, … • see Jesse Burns session on Android app security App Store Malware • Hackers have been working on the jailbroken side • 100 million devices, 250’000 apps, 4 billion downloads • February 2010 BlackHat DC USA • iPhone / App Store is not immune from malware http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-dc-10/Seriot_Nicolas/ BlackHat-DC-2010-Seriot-iPhone-Privacy-wp.pdf Agenda 1. Privacy issues overview 2. What can iPhone spyware do? 1. Access personal data 2. Fool App Store’s reviewers 3. Attack scenarios 4. Recommendations and conclusion 1. Privacy Issues Overview Security Issues Timeline …2007 2008 2009 2010… Root libtiff CoreAudio exploits SMS fuzzing FreeType Pulled Aurora Faint from Store MogoRoad SSL Trust you own Lawsuit Storm8 s Analytic PinchMedia concerns s Worms Ikee & co. (jailbreak) OS 1.0 1.1 2 2 2.2 3.0 3.1 3.2 4 4.1 Jailbreak SSH Worms Ikee Dutch 5 € ransom Root Exploit through PDF Handling ArsTechnica, August 2010 http://arstechnica.com/apple/news/2010/08/web-based-jailbreak-relies-on-unpatched- mobile-safari-flaw.ars Analytics Frameworks • PinchMedia • Think Google Analytics for your app • July 2009 – bloggers raise privacy concerns • Users are not informed and can’t opt-out Storm8 Lawsuit http://www.theregister.co.uk/2009/11/06/iphone_games_storm8_lawsuit/ http://www.boingboing.net/lawsuits/Complaint_Storm_8_Nov_04_2009.pdf Pulled out from AppStore* • Aurora Feint – July 2008 • Sent contact emails in clear • 20 million downloads • MogoRoad – September 2009 • Sent phone number in clear • Customers got commercial calls * Both applications are back on AppStore after updating their privacy policy. -

Vmware Workspace ONE UEM Ios Device Management

iOS Device Management VMware Workspace ONE UEM iOS Device Management You can find the most up-to-date technical documentation on the VMware website at: https://docs.vmware.com/ VMware, Inc. 3401 Hillview Ave. Palo Alto, CA 94304 www.vmware.com © Copyright 2020 VMware, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright and trademark information. VMware, Inc. 2 Contents 1 Introduction to Managing iOS Devices 7 iOS Admin Task Prerequisites 8 2 iOS Device Enrollment Overview 9 iOS Device Enrollment Requirements 11 Capabilities Based on Enrollment Type for iOS Devices 11 Enroll an iOS Device Using the Workspace ONE Intelligent Hub 14 Enroll an iOS Device Using the Safari Browser 15 Bulk Enrollment of iOS Devices Using Apple Configurator 16 Device Enrollment with the Apple Business Manager's Device Enrollment Program (DEP) 17 User Enrollment 17 Enroll an iOS Device Using User Enrollment 18 App Management on User Enrolled Devices 19 3 Device Profiles 20 Device Passcode Profiles 22 Configure a Device Passcode Profile 23 Device Restriction Profiles 24 Restriction Profile Configurations 24 Configure a Device Restriction Profile 29 Configure a Wi-Fi Profile 30 Configure a Virtual Private Network (VPN) Profile 31 Configure a Forcepoint Content Filter Profile 33 Configure a Blue Coat Content Filter Profile 34 Configure a VPN On Demand Profile 35 Configure a Per-App VPN Profile 38 Configure Public Apps to Use Per App Profile 39 Configure Internal Apps to Use Per App Profile 39 Configure an Email Account Profile 40 Exchange ActiveSync (EAS) Mail for iOS Devices 41 Configure an EAS Mail Profile for the Native Mail Client 41 Configure a Notifications Profile 43 Configure an LDAP Settings Profile 44 Configure a CalDAV or CardDAV Profile 44 Configure a Subscribed Calendar Profile 45 Configure Web Clips Profile 45 Configure a SCEP/Credentials Profile 46 Configure a Global HTTP Proxy Profile 47 VMware, Inc. -

Movie Deal. Buy a Mac and Final Cut Express HD

Save $200 Movie deal. Buy a Mac and Final Cut Express HD. Save $200. Purchase any Mac computer and Final Cut Express HD from January 1 to March 27, 2007, and receive $200 back via mail-in rebate.* You’ll have everything you need to edit professional-quality HD or DV movies. And since every Mac comes loaded with iLife, you’ll also be able to create blogs, podcasts, and websites to share your movies.** Hurry, your audience is waiting. * After mail-in rebate. Terms and conditions apply. **Some features in iLife require .Mac. The .Mac service is available to persons age 13 and older. Annual membership fee and Internet access required. Terms and conditions apply. Buy a Mac and Final Cut Express HD. Save $200. Purchase an Apple computer and Final Cut Express HD from January 1, 2007, to March 27, 2007. Products must be purchased together from an Apple Authorized Reseller. Follow these steps to claim your rebate. For faster processing, please submit your claim online at www.apple.com/promo. 1. Indicate purchase location. Reseller name: _________________________________________________________________________ 2. Attach a copy of your itemized sales receipt(s). Receipts must include reseller name and address (required). 7 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 2 (1P) Part No. MXXXXLL/A 3. Attach original UPC bar code labels for the computer and the Final Cut Express HD box (required). UPC bar (S) Serial No QTXXXXXXXX MXXXXLL/A Model No: MXXXX code labels must be cut from the box and include all layers of cardboard backing. Rebates cannot be honored XXX/XXX/XXX.XXXXXX/XXXXX/XXXSAMPLE without the original UPC bar code labels. -

The Rise of Apple Inc: Opportunities and Challenges Garcia Marrero in the International Marketplace

The Rise of Apple Inc: Opportunities and Challenges Garcia Marrero in the International Marketplace The Rise of Apple Inc: Opportunities and Challenges in the International Marketplace Alberto Garcia Marrero Florida International University The Rise of Apple Inc: Opportunities and Challenges Garcia Marrero in the International Marketplace ABSTRACT Apple Inc. is one of the world’s leading multinational enterprises as measured by revenue, profits, assets, and brand equity. Its ascent has been rapid but not linear; it has experienced setbacks along the way. This paper will analyze Apple’s evolution over the past decade and future prospects, with an eye toward identifying opportunities and challenges for global expansion. 2 The Rise of Apple Inc: Opportunities and Challenges Garcia Marrero in the International Marketplace BACKGROUND In 1976, Apple Inc. began as a garage operation by three men: Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak and Ronald Wayne (Ellen Terrell, 2008). The entire company was based solely on the engineering genius of Wozniak and the entrepreneurial and innovative genius of Jobs. Wayne sold out his shares of Apple to Jobs and Wozniak. Only weeks after its founding, Jobs and Wozniak were the sole owners of the company when it was fully incorporated in 1977 (Terrell, 2008). The company was based on the design, manufacturing, and selling of a new kind of operating computer designed by Wozniak, revolutionizing the world of the personal computer. Apple I was soon superseded by its successor the Apple II, which became the platform for VisiCalc, the first ever spreadsheet program (Terrell, 2008). Apple saw growth like no other during its first ten years of life as sales, but overall revenue saw an exponential growth every four months. -

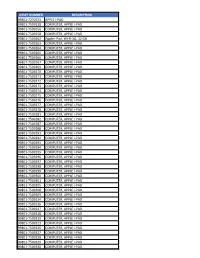

Asset Number Description 99801-7270733 Apple I-Pad

ASSET NUMBER DESCRIPTION 99801-7270733 APPLE I-PAD 99801-7507618 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509256 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509258 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509262 Apple i-Pad, WI-FI 3G, 32 GB 99801-7509263 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509264 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509265 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509266 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509267 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509269 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509270 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509271 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509272 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509273 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509274 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509275 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509276 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509277 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509278 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509281 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509282 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509287 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509288 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509291 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509292 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509293 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509294 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509295 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509296 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509297 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509298 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509299 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509300 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509301 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509305 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509308 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509309 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509314 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509316 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509317 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509318 COMPUTER, APPLE I-PAD 99801-7509319 COMPUTER, APPLE