A Place to Stand to Full Size the Black Community of Oak Bluffs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release Below to Your Local Media

Please forward the press release below to your local media. Thank you. Press Release: USA Student Wins World Neuroscience Competition August, 2017; Washington, DC, USA Future neuroscientists from 25 countries around the world met in Washington, DC this week to compete in the nineteenth World Brain Bee Championship. The Brain Bee is a neuroscience competition for young students, 13 to 19 years of age. It was hosted by the American Psychological Association. The International Brain Bee President and Founder is Dr. Norbert Myslinski ([email protected]) of The University of Maryland Dental School, Department of Neural and Pain Sciences. Its purpose is to motivate young men and women to study the brain, and to inspire them to enter careers in the basic and clinical neurosciences. We need bright young men and women to help treat and find cures for the 1000 neurological and psychological disorders around the world. The Brain Bee "Builds Better Brains to Fight Brain Disorders.” The 2017 World Brain Bee Champion is Sojas Wagle, a sophomore from Har-Ber High School in Arkansas, USA. Legend: Sojas Wagle Sojas has a breath taking history of accomplishments. He is the captain of his school’s Quiz Bowl Team, and was state MVP for the last two years. He placed third in the National Geographic Bee in 2015. Last year, he was chosen for “Who Wants to be a Millionaire” Whiz Kids Edition. By the end of the game show, he had won $250,000, and later donated some of his winnings to his school district and a children’s hospital. -

Dorothy West: the Last Writer of the Harlem Renaissance

Dorothy West: The Last Writer of the Harlem Renaissance Dorothy West's first long book was published when she was more than forty years old. Her second book was published when she was in her late eighties. Yet African-American poet Langston Hughes called her "The Kid." This means a child. Dorothy West had been one of the youngest members of the group of writers and artists of the Harlem Renaissance. This was a creative period for African-Americans during the 1920s and 1930s. During and after World War I, thousands of southern blacks moved to northern cities in the United States. They were seeking jobs and better lives. Many settled in an area of New York City known as Harlem. Many were musicians, writers, artists and performers. Harlem became the largest Dorothy West African-American community in the United States. The mass movement from South to North led African-Americans to examine their lives: Who were they? What were their rights as Americans? The artistic expression of this collective examination became known as the Harlem Renaissance. Renaissance means rebirth. The Harlem Renaissance represented a rebirth of black people as an effective part of American life. Dorothy West helped influence the direction and form of African-American writing during this time. Dorothy West was born in 1907 in the city of Boston, Massachusetts. Both her parents were born in the southern United States, and moved north. Her father was a former slave. He became the first African-American to own a food-selling company in Boston. The family became part of the black upper middle class social group of Boston. -

African-American Psychology and the Works of Gayl Jones

AFRICAN-AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGY AND THE WORKS OF GAYL JONES ABDUL QUADIR Research Scholar Department of English Jai Prakash University, Chapra (BH) INDIA Jones’ work has frequently been challenged on account of her questionable subjects just as news inclusion of her own life, her work keeps on awing peruses with its unpredictable style and profundity of feeling. She attracts a significant number of the subjects her accounts from her African-American legacy just as her very own life and battles. Maybe generally significant all through the mental advancements in the characters are their voices which yell from the pages of her work their story, their melody, and their fact. Her peruses can't hold back to hear what will come next from this calm lady who works so anyone can hear. Keywords: Gayl Jones, Slavery, Brutality, Racism, Classic Blues, Diaspora, Black INTRODUCTION A profoundly respected and inventive voice of African-American women author, Gayl Jones is a Black American Poet, Novelist, Play Wright, Short Story Writer, Professor and scholarly critic and was destined to Franklin and Lucille Jones on November 23, 1949 in Lexington, Kentucky, Jones early associations with the south are reflected unequivocally in her own life just as in her composition, which frequently rejuvenates Kentucky culture and characters for the peruses. As a striking novelistic voice apparently at progress with her tranquil, baffling persona, Gayl Jones shocked the abstract world during the 1970s with various books of African Americans battling to adapt to the tradition of Race, Violence, Slavery and Female Subjectivity. Both the structure and topic of her work are drawn from the dark oral custom. -

![1939-07-16 [P A-6]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1272/1939-07-16-p-a-6-1361272.webp)

1939-07-16 [P A-6]

CarCi a of County Hospital, Chicago, before Tuesday at 2:30 p.m. at the Jos- other large structure* throughout Clanks Dfatlja I here. for Food coming eph Oawlers Sons’ funeral home, the $50,000,000 Sea GARNER. JAMES B. We wish to ex- GENTRY. MERCER FRANK. Departed REDDEN. ISABEL HIGGLES. On Thurs- Dr. A. United States and Europe, died M. Curtis, Sr., He is survived by his Mrs. 1756 P street with burial in tend our sincere thanks for the beautiful this life Thursday. July 13. 1939. at 9:20 day. July 13. 1939. at the home of her mother, N.W., today at his summer home In Port Nearly $50,000,000 worth of A flora! offering and your expression of a m after a brief illness. MERCER FRANK son-in-law Mr Thomas Bodine. Cropley. Eleanora Curtis, Chicago; two sons, Arlington (Va.) National Cemetery. •ympathy In our ssd bereavement. GENTRY. He leaves to mourn their loss Md.. I6ABEL R1GGLES REDDEN, beloved Island. He and other sea food were In • Dr. A. M. Curtis, Washington, Long also shipped FAMILY. a Bessie Gentry: three brothers. wife of the late William Thomas jr., Patterson, N. MRS MARY HOLLINS AND sister. Redden. had a Douglass. William B and Clarence Gentry, Remains resting at the funeral home of Retired Howard U. and Dr. Merrill this home in Sarasota, Fla. Britain In the last 12 months. TERCERO. JOSE.* We wish to thank our J., Curtis, city; and a host of other relatives and friends. Reuben 7005 friends for their kind expressions of William PumPhrey. -

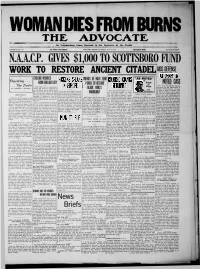

T H E : Work to Restore Ancient Citadel

WOMAN DES FROM BURNS T H E a d v o c a t e : An Indopandcnt Papwr D«vo(«d to lh« IntwrtoU m f th* Peopl* VOLUME SI NO. - S I IN TWO SECTIONS PORTLAND. OREGON. SATURDAY. JULY JO. IMS SECTION ONE PRICB FIVE CENTS N.A.A.C.P. GIVES $1,000 TO SC0TTSB0R0 FUND WORK TO RESTORE ANCIENT CITADEL AIDS DEFENSE EXCLUDE NEGROES FRIENDS OF HAITI SEND A S N O T E D * * Digesting . * Ralph FROM BOULDER CITY FUNDS Ï0 RESTORE C. NOTED CASE . ( V e v ^ s New York, July 22-The National The NEW YORK. July 10— Althougb teu Clyde Association for the Advancement of UY CLirrOKD C MITCHELL cnlored nixu bava been xiuployxil al BLACK KING'S Colored People has sent its check th» uxw lloover ilam al lluuldxr City. City Gllkerson's Colored Giant# will re for 11000 to Walter H. Pollack, lead Nev . they hâve no i|uartxra al tloul New York, July 33—Word has been Commissioner turn to Portland Monday to start ing New York lawyer, who la appeal d«r l'Iiy ami muai commuta 29 mile« received here that Williams Pickens, their three game series with the ing the case of the condemned Scot- nacli way aarh ilay lo rwaeh tbalr Joba. field secretary of the Natlooal Asso POWER TRUST AIDED RECEIVERSHIP West Side Babes at Vaughn street taboro boys to the United States Su accord Ing lo information «ont the ciation for Ihe Advancement of Col Park The games will be played Mon preme court The N.A-A.C.P. -

47 Free Films Dealing with Racism That Are Just a Click Away (With Links)

47 Free Films Dealing with Racism that Are Just a Click Away (with links) Ida B. Wells : a Passion For Justice [1989] [San Francisco, California, USA] : Kanopy Streaming, 2015. Video — 1 online resource (1 video file, approximately 53 min.) : digital, .flv file, sound Sound: digital. Digital: video file; MPEG-4; Flash. Summary Documents the dramatic life and turbulent times of the pioneering African American journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader of the post-Reconstruction period. Though virtually forgotten today, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a household name in Black America during much of her lifetime (1863-1931) and was considered the equal of her well-known African American contemporaries such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice documents the dramatic life and turbulent times of the pioneering African American journalist, activist, suffragist and anti-lynching crusader of the post-Reconstruction period. Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison reads selections from Wells' memoirs and other writings in this winner of more than 20 film festival awards. "One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap." - Ida B. Wells "Tells of the brave life and works of the 19th century journalist, known among Black reporters as 'the princess of the press, ' who led the nation's first anti-lynching campaign." - New York Times "A powerful account of the life of one of the earliest heroes in the Civil Rights Movement...The historical record of her achievements remains relatively modest. This documentary goes a long way towards rectifying that egregious oversight." - Chicago Sun-Times "A keenly realized profile of Ida B. -

The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2005 Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West Tamara Jenelle Williamson University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Williamson, Tamara Jenelle, "Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2538 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Tamara Jenelle Williamson entitled "Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary E. Papke, Nancy Goslee Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Tamara Jenelle Williamson entitled “Renaissance Woman: The Works and Critical Reception of Dorothy West.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. -

Jones, Lois Mailou

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 JONES, LOIS MAILOU MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "JONES, LOIS MAILOU" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 112. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOIS MAILOU JONES Collection 215-1 to 215-80 Prepared by: Ida Jones April 2007 MANUSCRIPT DIVISION Scope note The papers of Lois Mailou Jones Pierre-Noèl (1905-1998), visual artist, educator, scholar and mentor cover the time period 1920-1998. Lois Mailou Jones served as a professor of art at the Howard University College of Fine Arts from 1930-1967. The collection includes 18 series: personal papers, family papers, correspondence, financial records, Howard University/teaching materials, writings by LMJ, writings about LMJ, writings by others, Pierre-Noel studios/illustrations, subject files, catalogs/brochures, books, clipping files, photographs, artifacts, audiovisual materials, oversize materials and scrapbooks. These various series contain materials documenting the life of LMJ as artist and the history and evolution of art. There are approximately 80 linear feet of material. The papers were donated by Lois Mailou Jones and deposited at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center by Dr. Chris Chapman. The bulk of the materials documents the professional life of Lois Mailou Jones in the role of artistic mentor and Howard University faculty member. -

F the C U L V E R . C IT IZ

f The C U LV ER . C IT IZ E N ON LAKI: MAXINKUCKEE— INDIANA'S MOST BEAUTIFUL LAKE V O L U M E L V I CULVER, INDIANA, W EDNESDAY, JANUARY 4,1950 N U M B E R 4 2 Lakers Face South Plan Tri-Township Remind Taxpayers Indians Resume Chronology of 1949 Bend Tonight; Meet Farmers Institute Of Deadline for Net Schedule Events from August The Tri-Township Farmers' In Culver— Argos athletic rivalry Laporte Tuesday stitute will be held at West High Final Payments will be renewed on Friday evening Through December School on the evening of February when the local Indians sporting a record of 7 wins and 3 losses 8 and all day on February 9, it (Continued from last week.) The Culver Lakers remain un- Thousands of farmers, bus>- was announced this week. will engage the Green Dragons i defeated on their home floor as a inessmen, and other taxpayers of Note: Last week the happen This is a cooperative event plan there. On Saturday evening the result of their 63 to 59 victory the Indiana district were remind ings as revealed in The Citizen ned hy the three townships. West, Sering-coached squad will meet ^B pver tin; Lafayette American Le- ed this week by Ralph W . Cripe, each week from January 1st Green, and Union. The officers for Delphi high school here in the ^^K 'ion team last Thursday. W ith the collector of Internal Revenue, through August 24th were report- the 1950 Institute are Dr. Oscar tied 26 to 26 at the half, that January 16 is the deadline I. -

Dorothy West's Re-Imagining of the Migration Narrative

Dorothy West's Re-imagining of the Migration Narrative Alexis Victoria Elizabeth Michelle Harper Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English Virginia C. Fowler Gena E. Chandler – Smith Nikki Giovanni 09/29/2016 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Literature, African American Literature, The Great Migration, Dorothy West, The Living is Easy Copyright 2016 Alexis Harper Dorothy West's Re-imagining of the Migration Narrative Alexis Victoria Elizabeth Michelle Harper This thesis explores Dorothy West's interpretation of the migration experience through her novel The Living is Easy. Dorothy West breaks new ground by documenting a Black female migrant’s sojourn from South to North in an era in which such narratives were virtually non-existent. West seemingly rejects both a separation between North and South as well any sentiment of condemning the North or South in totality. Instead, West chooses to settle her novel in a gray area. Moreover, in refusing to condemn the South, Dorothy West redeems the South from oversimplified negative assumptions of the region. My interpretation of Dorothy West's The Living is Easy as well as Cleo Judson both highlights West's contributions to the genre by complicating the assumptions of what a migration narrative contains by centering the migrating Black female body. Dorothy West's Re-imagining of the Migration Narrative Alexis Victoria Elizabeth Michelle Harper General Audience Abstract This thesis examined Dorothy West's Migration Narrative, The Living is Easy. Migration Narratives are a genre of African – American literature that concerns the historical period in the early 20th century in which thousands of Black Americans migrated from the regional South to the regional North and Midwest. -

Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector

The Artist and the Folk: Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector by Alexandra Hoffman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Anita Norich, Chair Professor Sandra Gunning Associate Professor Mikhail Krutikov Associate Professor Christi Merrill Associate Professor Joshua Miller Acknowledgements I am delighted that the writing process was only occasionally a lonely affair, since I’ve had the privilege of having a generous committee, a great range of inspiring instructors and fellow graduate students, and intelligent students. The burden of producing an original piece of scholarship was made less daunting through collaboration with these wonderful people. In many ways this text is a web I weaved out of the combination of our thoughts, expressions, arguments and conversations. I thank Professor Sandra Gunning for her encouragement, her commitment to interdisciplinarity, and her practical guidance; she never made me doubt that what I’m doing is important. I thank Professor Mikhail Krutikov for his seemingly boundless references, broad vision, for introducing me to the oral history project in Ukraine, and for his laughter. I thank Professor Christi Merrill for challenging as well as reassuring me in reading and writing theory, for being interested in humor, and for being creative in not only the academic sphere. I thank Professor Joshua Miller for his kind and engaged reading, his comparative work, and his supportive advice. Professor Anita Norich has been a reliable and encouraging mentor from the start; I thank her for her careful reading and challenging comments, and for making Ann Arbor feel more like home. -

The Republican Journal: Vol. 82, No. 2

THR? VOLUME 82.___ NUMBER 2 Contents of Journal. SUPREME out co«t6. Principal defendant defaulted; tember and the report was filed In November. Today’s JUDICIAL COURT. Jr. REMARKABLE WORK OF A BELFAST Ritchie; Brown, Monday the report of the referee was accept- PERSONAL. The Churches. fees of referee allowed as GIRL. .News of Belfast.... Leslie C. Cornish of INDICTMENTS. ed and the taxed v i. The Churches.. Judge Augusta and ordered out of the County C. W. The Spiritualist Society will hold services at Personal_Remarkable Work of a Jury reported paid treasury. Wegcott was in BangOr on business The Grand Thursday after- afternoon session was taken Miss Gladys Pitcher, only child of Mr. and ..Basket Ball.. Presiding. in The entire up 2 o’clock next afternoon in Kr.owlton’s Belfast Girl.. .Obitu- aftei being session but one Nine- Mrs. mu- the first of the week. Sunday noon, day. with the case of W. T. C. Runnells vs. Charles Elbridge S. Pitcher, both well-known of Waldo Vet- were hall on street. ary.. .Meeting County January 5th, Messrs. Lamont of teen indictmente found, of which 18 were was sicians of High O’Hanley F. Hill, Searsport This an action Belfast, .has just successfully passed Mrs. Estelle Mason of East Or was erans.Secret Societies.Waldo Gamble of made Of the seven parties. land the Swanville, John Frankfort, Neil public. respondents in- of The claimed that at times the junior examinations in piano at the New Valuation and Tax.. of violation of the trespass. plaintiff guest of Rev. and Mrs.