Brown and Lawrence (And Goodridge)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Jfk's Five-Year Campaign Thomas Oliphant, Curtis Wilkie

[pdf] The Road To Camelot: Inside Jfk’S Five-Year Campaign Thomas Oliphant, Curtis Wilkie - free pdf download Download Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Book, Read Best Book Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, PDF The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Full Collection, Read Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Ebook Popular, Free Download The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Full Version Thomas Oliphant, Curtis Wilkie, the book The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, I Was So Mad The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Thomas Oliphant, Curtis Wilkie Ebook Download, Download The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign E-Books, Download Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Book, Read Best Book Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, pdf free download The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, Read Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign E-Books, free online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, Download pdf The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, Thomas Oliphant, Curtis Wilkie epub The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign, The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Full Download, The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Book Download, Download Online The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Book, The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign Ebooks, -

Bay Windows Thursday Oct 30, 2008

Bay Windows Thursday Oct 30, 2008 State races It goes without saying that Bay Windows readers should go to the polls to vote on Election Day, but as the LGBT community learned over the last few years during the marriage debate, there’s more to democracy than just casting a vote. There are several candidates with strong positions on LGBT equality who deserve more than just the community’s vote on Election Day; we should be out in the district for these candidates holding signs and helping the candidates get out the vote. If you live in or near any of their districts and can take time off work on Election Day, contact their campaigns and offer your support as a volunteer. And check out the voter guide on page 4 to see all the LGBT endorsements. Among the top priorities is Sara Orozco’s campaign to unseat anti-gay Wrentham Sen. Scott Brown (Norfolk, Bristol and Middlesex district). Orozco is an out lesbian and a Needham psychologist who is particularly passionate about issues facing LGBT youth and elders, and she would be a wonderful addition to the Senate. And it would be poetic justice for an out lesbian to defeat Brown, who is a longtime opponent of marriage equality and who once criticized his predecessor, openly gay Cheryl Jacques, for having children with her partner, calling their family "not normal." Voters should also lend a hand on Election Day to Rep. Jamie Eldridge, who is campaigning to succeed retiring Sen. Pam Resor in the Middlesex and Worcester seat. Eldridge was one of the lawmakers on the frontlines of the fight to protect marriage equality, and he would continue Resor’s legacy of support for LGBT rights in the Senate. -

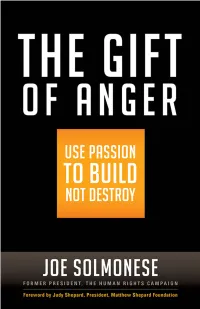

The Gift of Anger: Use Passion to Build Not Destroy

If you enjoy this excerpt… consider becoming a member of the reader community on our website! Click here for sign-up form. Members automatically get 10% off print, 30% off digital books. The Gift of Anger The Gift of Anger Use Passion to Build Not Destroy • Joe Solmonese • The Gift of Anger Copyright © 2016 by Joe Solmonese All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distrib- uted, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior writ- ten permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc. 1333 Broadway, Suite 1000 Oakland, CA 94612-1921 Tel: (510) 817-2277, Fax: (510) 817-2278 www.bkconnection.com Ordering information for print editions Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by cor- porations, associations, and others. For details, contact the “Special Sales Department” at the Berrett-Koehler address above. Individual sales. Berrett-Koehler publications are available through most bookstores. They can also be ordered directly from Berrett-Koehler: Tel: (800) 929-2929; Fax: (802) 864-7626; www.bkconnection.com Orders for college textbook/course adoption use. Please contact Berrett- Koehler: Tel: (800) 929-2929; Fax: (802) 864-7626. Orders by U.S. trade bookstores and wholesalers. Please contact Ingram Publisher Services, Tel: (800) 509-4887; Fax: (800) 838-1149; E-mail: customer .service@ingram publisher services .com; or visit www .ingram publisher services .com/ Ordering for details about electronic ordering. -

Reach Out: the Newsletter of Maine Speakout Project (Fall 2005)

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Reach Out Periodicals Fall 2005 Reach Out: the newsletter of Maine Speakout Project (Fall 2005) Maine Speakout Project Community Counseling Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/reach_out Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Maine Speakout Project and Community Counseling Center, "Reach Out: the newsletter of Maine Speakout Project (Fall 2005)" (2005). Reach Out. 3. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/reach_out/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Periodicals at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reach Out by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. the newsletter of REACH Ou, Maine Speakout Project Fall 2005 • 343 Forest Avenue • Portland, ME 04101 • 207.874.1030 • tty 207.874.1043 SPEAK OUT Maine Speakout Project is a Progra111 of Community Counseling Center~ Summer at Maine Speakout Project Celebrating Our Progress, Remembering Our Losses This summer brought a lot of new and wonderful changes to MSOP. We moved offices in June. 2nd Annual MSOP is now housed with Community Counseling Center's Deaf Counseling Services at 43 Baxter Transgender Day of Remembrance Boulevard. Our new space is bright and open and located conveniently near Hannaford and Back Saturday, November 19, 2005 Cove. While our mailing address has remained the same, 43 Baxter has given us the opportunity to expand the office and re-open the Charlie Howard Memorial Library (CHML). -

Guide to the Human Rights Campaign Records, 1975-2005. Collection Number: 7712

Guide to the Human Rights Campaign Records, 1975-2005. Collection Number: 7712 Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections Cornell University Library Contact Information: Compiled Date EAD Date Division of Rare and by: completed: encoding: modified: Manuscript Collections Brenda February 2007 Peter Martinez Jude Corina, 2B Carl A. Kroch Library Marston, Rima and Evan Fay June 2015 Cornell University Turner Earle, February Ithaca, NY 14853 2007 (607) 255-3530 Sarah Keen, Fax: (607) 255-9524 January 2008 [email protected] Sarah Keen, June http://rmc.library.cornell.edu 2009 Christine Bonilha, October 2010- April 2011 Bailey Dineen, February 2014 © 2007 Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Title: Human Rights Campaign records, 1975-2005. Collection Number: 7712 Creator: Human Rights Campaign (U.S.). Quantity: 109.4 cubic feet Forms of Material: Correspondence, Financial Records, Photographs, Printed Materials, Publications Repository: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library Abstract: Project files, correspondence, financial and administrative records, subject files, press clippings, photographs, and miscellany that, taken together, provide a broad overview of the American movement for lesbian, gay, transgender, and bisexual rights starting in 1980. HRC(F)'s lobbying, voter mobilization efforts, and grassroots organizing throughout the United States are well documented, as are its education and outreach efforts and the work of its various units that have -

Video File Finding

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MAIN VIDEO FILE ● MVF-001 NBC NEWS SPECIAL REPORT: David Frost Interviews Henry Kissinger (10/11/1979) "Henry Kissinger talks about war and peace and about his decisions at the height of his powers" during four years in the White House Runtime: 01:00:00 Participants: Henry Kissinger and Sir David Frost Network/Producer: NBC News. Original Format: 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape Videotape. Cross Reference: DVD reference copy available. DVD reference copy available ● MVF-002 "CNN Take Two: Interview with John Ehrlichman" (1982, Chicago, IL and Atlanta, GA) In discussing his book "Witness to Power: The Nixon Years", Ehrlichman comments on the following topics: efforts by the President's staff to manipulate news, stopping information leaks, interaction between the President and his staff, FBI surveillance, and payments to Watergate burglars Runtime: 10:00 Participants: Chris Curle, Don Farmer, John Ehrlichman Keywords: Watergate Network/Producer: CNN. Original Format: 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape Videotape. DVD reference copy available ● MVF-003 "Our World: Secrets and Surprises - The Fall of (19)'48" (1/1/1987) Ellerbee and Gandolf narrate an historical overview of United States society and popular culture in 1948. Topics include movies, new cars, retail sales, clothes, sexual mores, the advent of television, the 33 1/3 long playing phonograph record, radio shows, the Berlin Airlift, and the Truman vs. Dewey presidential election Runtime: 1:00:00 Participants: Hosts Linda Ellerbee and Ray Gandolf, Stuart Symington, Clark Clifford, Burns Roper Keywords: sex, sexuality, cars, automobiles, tranportation, clothes, fashion Network/Producer: ABC News. -

The Federal Marriage Amendment and the False Promise of Originalism

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2008 The Federal Marriage Amendment and the False Promise of Originalism Thomas Colby George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas B. Colby, The Federal Marriage Amendment and the False Promise of Originalism, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 529 (2008). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\server05\productn\C\COL\108-3\COL301.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-MAR-08 12:26 COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 108 APRIL 2008 NO. 3 ARTICLES THE FEDERAL MARRIAGE AMENDMENT AND THE FALSE PROMISE OF ORIGINALISM Thomas B. Colby* This Article approaches the originalism debate from a new angle— through the lens of the recently defeated Federal Marriage Amendment. There was profound and very public disagreement about the meaning of the FMA—in particular about the effect that it would have had on civil unions. The inescapable conclusion is that there was no original public meaning of the FMA with respect to the civil unions question. This suggests that often the problem with originalism is not just that the original public meaning of centuries-old provisions of the Constitution is hard to find (especially by judges untrained in history). The problem is frequently much more funda- mental, and much more fatal; it is that there was no original public mean- ing to begin with. -

Elliot Richardson and the Search for Order on the Oceans (1977-1980)

Crafting the Law of the Sea: Elliot Richardson and the Search for Order on the Oceans (1977-1980) Vivek Viswanathan Harvard College 2009 M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series | No. 3 Winner of the 2009 John Dunlop Undergraduate Thesis Prize in Business and Government The views expressed in the M-RCBG Fellows and Graduate Student Research Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series have not undergone formal review and approval; they are presented to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall | Harvard Kennedy School | www.hks.harvard.edu/mrcbg CRAFTING THE LAW OF THE SEA Elliot Richardson and the Search for Order on the Oceans 1977-1980 by Vivek Viswanathan A thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts With Honors Harvard University Cambridge Massachusetts March 19, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: “The Man for All Seasons”…………………………………………………3 1. “A Constitution for the Oceans”………………………………………………………21 2. “On the Point of Resolution”………………………………………………………….49 3. “‘Fortress America’ Is Out of Date”…………………………………………………..83 Conclusion: “To Adapt and Endure”…………………………………………………..114 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………….126 Introduction “The Man for All Seasons” Between 1969 and 1980, Elliot Lee Richardson served in a succession of influential positions in American government: Under Secretary of State; Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare; Secretary of Defense; Attorney General; Ambassador to the Court of St. -

Race and Presidential Politics '92: the Hc Allenge to Go Another Way May Louie National Rainbow Coalition

Trotter Review Volume 6 Article 5 Issue 2 Race and Politics in America: A Special Issue 9-21-1992 Race and Presidential Politics '92: The hC allenge to Go Another Way May Louie National Rainbow Coalition Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Politics Commons, American Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Louie, May (1992) "Race and Presidential Politics '92: The hC allenge to Go Another Way," Trotter Review: Vol. 6: Iss. 2, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol6/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trotter Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Race and Presidential Politics '92: The Challenge to Go Another Way by May Louie "The problem ofthe twentieth century is the problem of the color line." - W. E. B. Du Bois At presidential election time in 1 992, America is once again looking at limited political options for national leadership. The Republican party platform is its most conservative ever. The Democratic party ticket is domi- nated by southern Dixiecrats. And we who have marched and organized, and risked and sacrificed much for racial equality and political empowerment, must now match our sense of foreboding with our determination to meet the challenge before us. Jesse Jackson's 1984 and 1988 be a historic changing of the guard in the U.S. -

Before the Federal Election Commission

BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION In the Matter of Commission on.Presidential Debates, Frank Fahrenkopf, Jr., Michael D. McCurry, Howard G. Buffett, John C. Danforth, John Griffen, Antonia Hernandez, John I. Jenkins, Newton N. Minow, Richard D. Parsons, Dorothy Ridings, Alan K. Simpson, and Janet Brown COMPLAINT SHAPIRO, ARATO &, ISSERLES LLP 500 Fifth Avenue 40th Floor New York, New York lOIlO Phone: (212)257-4880 Fax: (212)202-6417 Attorneys for Complainants Level the Playing Field and Peter Ackerman TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS i TABLE OF EXHIBITS iii PRELIMINARY STATEMENT I BACKGROUND 6 A. The Parties , 6 B. Regulatory Framework 8 C. The Commission On Presidential Debates As Debate Sponsor 11 THE CPD VIOLATES THE PEG'S DEBATE STAGING RULES 14 I. THE CPD IS NOT A NONPARTISAN ORGANIZATION; IT SUPPORTS THE DEMOCRATIC AND REPUBLICAN PARTIES AND OPPOSES THIRD PARTIES AND INDEPENDENtS 15 A. The Democratic And Republican Parties Created The CPD As A Partisan Organization 16 B. The CPD Has Consistently Supported The Democratic And Republican Parties And Opposed Third Parties And Independents 20 C. The CPD Is Designed To Further Democratic And Republican Interests 25 II. THE CPD USES SUBJECTIVE CANDIDATE SELECTION CRITERIA THAT ARE DESIGNED TO EXCLUDE THIRD-PARTY AND INDEPENDENT CANDIDATES 32 A. The 15% Rule Is Not Objective 33 1. The 15% Rule Is Designed To Select Republican And Democratic Candidates And Exclude Third-Party And Independent Candidates 34 2. The CPD's 15% Rule Is Biased Because It Systematically Disfavors Third-Party And Independent Candidates 40 3. The Timing Of The CPD's Determination Is Biased And Designed To Exclude Third-Party And Independent Candidates 44 4. -

Civil Rights in the New Millennium by Swanee Hunt, Scripps Howard News Service, July 20, 2005

Civil Rights in the New Millennium by Swanee Hunt, Scripps Howard News Service, July 20, 2005 When Cheryl Jacques walks into a room, she commands attention. Tall, elegant, and professional, she has a broad smile and firm handshake. The proud mother of mischievous twin three year-old boys, Cheryl balances her rewarding family life with a robust career. An accomplished lawyer, she served six terms in the Massachusetts State Senate and was known for authoring one of the nation’s toughest gun control laws. She currently practices law in Boston and will be a Fellow at Harvard’s Institute of Politics this fall. Cheryl has long been an outspoken leader in the modern civil rights movement; in fact, she’s gay. Many gays and lesbians share their sexual identity—and the many challenges they face —with family and friends. Still, many straight Americans don’t know what gays are really up against. In 34 states, they can be fired based on sexual orientation alone. When Cheryl told her father about this fact, he reacted as many do: “Not in America!” But it’s true, and that’s only one strand of a larger pattern of discrimination. In hospitals around the country, gays and lesbians are often prevented from visiting loved ones during medical emergencies because they’re not legally recognized as next of kin. Cheryl shared with me the story of a woman who recently passed away after a long battle with cancer. The coroner refused to allow her life partner to sign the death certificate. What a bitter moment for the woman who had nursed her for a year and a half. -

Press Galleries*

PRESS GALLERIES* SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Senior Media Coordinator.—Merri I. Baker Media Coordinators: James D. Saris Amy M. Harkins Wendy A. Oscarson HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945, 225–6722 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Emily T. Dupree Ric Andersen Drew Cannon Laura Reed STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Scott Shepard, Cox News Service, Chairman Jack Torry, Columbus Dispatch, Secretary Jim Drinkard, USA Today Mary Agnes Carey, Congressional Quarterly Jesse Holland, The Associated Press RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration.