An In-Depth Analysis of Bilateral Relations Based Upon the Czech Sources Ioannis Koreček / Ιωάννης Κορετσεκ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Patrick Publishing Company, Inc

Saint George Parish Community Under the Guidance of the Holy Spirit 22 E. Cooke Avenue, Glenolden, PA 19036 - 610-237-1633 - www.stgeorgeparish.org 14th Sunday in Ordinary Time July 4, 2021 Jesus departed from there and came to His na- tive place, accompanied by His disciples. When the sabbath came, He began to teach in the syna- gogue, and many who heard Him were aston- ished. They said, “Where did this Man get all this? What kind of wisdom has been given Him? What mighty deeds are wrought by His hands! Is He not the carpenter, the Son of Mary, and the brother of James and Joses and Judas and Si- mon? And are not His sisters here with us?” And they took offense at Him. Jesus said to them, “A prophet is not without honor except in His native place and among His own kin and in His own house.” So He was not able to perform any mighty deeds there, apart from curing a few sick people by laying His hands on them. He was amazed at their lack of faith. ~Mark 6: 1-6a Happy Independence Day! God our Father, Giver of life, we entrust the United States of America to Your loving care. You are the rock on which this nation was founded. You alone are the true source of our cherished rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Reclaim this land for Your glory and dwell among Your people. Send Your Spirit to touch the hearts of our nation´s leaders. Open their minds to the great worth of human life and the responsibilities that accompany human freedom. -

Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 1 Spring 1984 Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World Charles A. Frazee Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Frazee, Charles A. (1984) "Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol5/iss1/1 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Vincentian Missions in the Islamic World Charles A. Frazee When Saint Vincent de Paul organized the Congrega- tion of the Mission and the Daughters of Charity, one of his aims was to provide a group of men and women who would work in foreign lands on behalf of the Church. He held firm opinions on the need for such a mission since at the very heart of Christ's message was the charge to go to all nations preaching the Gospel. St. Vincent believed that the life of a missionary would win more converts than theological arguments. Hence his instructions to his dis- ciples were always meant to encourage them to lead lives of charity and concern for the poor. This article will describe the extension of Vincent's work into the Islamic world. Specifically, it will touch on the Vincentian experience in North Africa, the Ottoman Empire (including Turkey, the Near East, and Balkan countries), and Persia (Iran). -

'Made in China': a 21St Century Touring Revival of Golfo, A

FROM ‘MADE IN GREECE’ TO ‘MADE IN CHINA’ ISSUE 1, September 2013 From ‘Made in Greece’ to ‘Made in China’: a 21st Century Touring Revival of Golfo, a 19th Century Greek Melodrama Panayiota Konstantinakou PhD Candidate in Theatre Studies, Aristotle University ABSTRACT The article explores the innovative scenographic approach of HoROS Theatre Company of Thessaloniki, Greece, when revisiting an emblematic text of Greek culture, Golfo, the Shepherdess by Spiridon Peresiadis (1893). It focuses on the ideological implications of such a revival by comparing and contrasting the scenography of the main versions of this touring work in progress (2004-2009). Golfo, a late 19th century melodrama of folklore character, has reached over the years a wide and diverse audience of both theatre and cinema serving, at the same time, as a vehicle for addressing national issues. At the dawn of the 21st century, in an age of excessive mechanization and rapid globalization, HoROS Theatre Company, a group of young theatre practitioners, revisits Golfo by mobilizing theatre history and childhood memory and also by alluding to school theatre performances, the Japanese manga, computer games and the wider audiovisual culture, an approach that offers a different perspective to the national identity discussion. KEYWORDS HoROS Theatre Company Golfo dramatic idyll scenography manga national identity 104 FILMICON: Journal of Greek Film Studies ISSUE 1, September 2013 Time: late 19th century. Place: a mountain village of Peloponnese, Greece. Golfo, a young shepherdess, and Tasos, a young shepherd, are secretly in love but are too poor to support their union. Fortunately, an English lord, who visits the area, gives the boy a great sum of money for rescuing his life in an archaeological expedition and the couple is now able to get engaged. -

Königs-Und Fürstenhäuser Aktuelle Staatsführungen DYNASTIEN

GESCHICHTE und politische Bildung STAATSOBERHÄUPTER (bis 2019) Dynastien Bedeutende Herrscher und Regierungschefs europ.Staaten seit dem Mittelalter Königs-und Fürstenhäuser Aktuelle Staatsführungen DYNASTIEN Römisches Reich Hl. Römisches Reich Fränkisches Reich Bayern Preussen Frankreich Spanien Portugal Belgien Liechtenstein Luxemburg Monaco Niederlande Italien Großbritannien Dänemark Norwegen Schweden Österreich Polen Tschechien Ungarn Bulgarien Rumänien Serbien Kroatien Griechenland Russland Türkei Vorderer Orient Mittel-und Ostasien DYNASTIEN und ihre Begründer RÖMISCHES REICH 489- 1 v.Chr Julier Altrömisches Patriziergeschlecht aus Alba Longa, Stammvater Iulus, Gaius Iulius Caesar Julisch-claudische Dynastie: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero 69- 96 n.Ch Flavier Röm. Herrschergeschlecht aus Latium drei römische Kaiser: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian 96- 180 Adoptivkaiser u. Antonionische Dynastie Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Mark Aurel, Commodus 193- 235 Severer Aus Nordafrika stammend Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabal, Severus Alexander 293- 364 Constantiner (2.flavische Dynastie) Begründer: Constantius Chlorus Constantinus I., Konstantin I. der Große u.a. 364- 392 Valentinianische Dynastie Valentinian I., Valens, Gratian, Valentinian II. 379- 457 Theodosianische Dynastie Theodosius I.der Große, Honorius, Valentinian III.... 457- 515 Thrakische Dynastie Leo I., Majorian, Anthemius, Leo II., Julius Nepos, Zeno, Anastasius I. 518- 610 Justinianische Dynastie Justin I.,Justinian I.,Justin II.,Tiberios -

The Collapsing Bridge of Civilizations: the Republic Of

ETHNICITY, RELIGION, NATURAL RESOURCES, AND SECURITY: THE CYPRIOT OFFSHORE DRILLING CRISIS By: GREGORY A. FILE Bachelor of Science Political Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May, 2012 ETHNICITY, RELIGION, NATURAL RESOURCES, AND SECURITY: THE CYPRIOT OFFSHORE DRILLING CRISIS Thesis Approved: Dr. Nikolas Emmanuel Thesis Adviser Dr. Joel Jenswold Committee Member Dr. Reuel Hanks Committee Member Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College i TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………....1 Synopsis……………………………………………………………………....1 Literature Review………………………………………………………….....5 Why Alliances Form……………………………………………….....5 Regional Security Complex Theory…………………………………..6 Ethnic Similarity……………………………………………………...6 Religious Similarity…………………………………………………...8 Hydrocarbon Trade…………………………………………………...10 Security Concerns…………………………………………………….12 Culture and Non-Culture Theory…………………………………………......14 Culture………………………………………………………………..14 Non-Culture…………………………………………………………..16 Methods………………………………………………………………………18 Small – N……………………………………………………………..19 Case Selection………………………………………………………...19 Methodology……………………………………………………….....21 ii Chapter Page II. CYPRUS: THE PIVOT…………………………………………………………28 History……………………………………………………………………….28 The Demographics of Cyprus……………………………………………….33 The Grievances………………………………………………………………36 The Offshore Drilling Crisis…………………………………………………38 -

Acropolis Statues Begin Transfer to New Home Christodoulos Now

O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans A WEEKLY GREEK AMERICAN PUBLICATION c v www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 11, ISSUE 523 October 20, 2007 $1.00 GREECE: 1.75 EURO Acropolis Statues Begin Transfer to New Home More than 300 Ancient Objects will be Moved to New Museum Over the Next Four Months By Mark Frangos Special to the National Herald ATHENS — Three giant cranes be- gan the painstaking task Sunday, October 14 of transferring hun- dreds of iconic statues and friezes from the Acropolis to an ultra-mod- ern museum located below the an- cient Athens landmark. The operation started with the transfer of part of the frieze at the northern end of the Parthenon. That fragment alone weighed 2.3 tons and in the months to come, the cranes will move objects as heavy as 2.5 tons. Packed in a metal casing the frieze, which shows a ancient reli- gious festival in honor of the god- dess Athena, was transferred from the old museum next to the Parthenon to the new one 984 feet below. Under a cloudy sky, with winds AP PHOTO/THANASSIS STAVRAKIS of 19 to 24 miles an hour, the three Acropolis Museum cranes passed the package down to its new home, in an operation that "Everything passed off well, de- lasted one and a half hours. spite the wind," Zambas told AFP. Following the operation on site Most of the more than 300 more AP PHOTO/THANASSIS STAVRAKIS was Culture Minister Michalis Li- ancient objects should be trans- A crane moves a 2.3-ton marble block part of the Parthenon frieze to the new Acropolis museum as people watch the operation in Athens on Sunday, apis, who also attended Thursday's ferred over the next four months, October 14, 2007. -

"„ , Six Years Ago the Letter Z Suddenly Appeared Everywhere in Athens; on Walls, on Sidewalks, on Posters, Even on Official Government Bulletins

"„ , Six years ago the letter Z suddenly appeared everywhere in Athens; on walls, on sidewalks, on posters, even on official government bulletins. Z stands for the Greek verb 2E1, "he lives." "He" was Gregorios Lambrakis . ,t THE LAMBRAKIS AFFAIR • On the threshing floors where one, isight-the -brave-danced - the olive pits remain and the crusted blood of the moon and the epic fifteen syllable of their guns. The cypress remains. And the laurel. • Yannis Moos Wednesday May 22, 1963, in Salonica, Gregorios Lambrakis, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Athens, a deputy aligned with the EDA party (Union of the Democratic Left) and chairman of the Greek Committee for Peace, addressed a rally protesting the placement of Polaris missiles in Greece. As he left the assembly hall he was knocked down by a three wheeled delivery truck. Taken unconscious to the hospital, he died three days later without ever regain- ing consciousness. Thanks to the spontaneous intervention of a peace demonstra- tor, the driver of the truck, Spiros Gotzamanis, was arrested the same evening. His accomplice, E. Emmanouelidis, was arrested several days later. Earlier the same evening, a second deputy of EDA, George Tsarouhas, was beaten unmerci- fully by organized "counterdemonstrators, " thugs of a right-wing paramilitary organization. As Lambrakis was ushered to his grave by 400,000 Greeks, the largest crowd Athens has ever seen, the government and the pro-government papers described the incident as a "regrettable traffic accident. " A large segment of the press, however, refused to accept the official version, and a post-mortem examination of Lambrakis' cranium revealed internal hemorraging which could not have been caused by a fall to the ground, but only by a blow from a blunt instrument. -

Berlin Painter 5Th C. Vases Exhibition in Washington, Kotzias Says US

S o C V st ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 101 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald anniversa ry N www.thenationalherald.com A weeKly GReeK-AMeRicAN PUblicAtioN 1915-2016 VOL. 20, ISSUE 1014 March 18-24, 2017 c v $1.50 Berlin In Washington, Kotzias Painter 5th Says US Backs Greek C. Vases Debt Relief, Talks Exhibition TNH Staff heading back to Athens, with US National Security Adviser Lt. WASHINGTON, D.C. – Visit - Gen. H.R. McMaster, Kotzias Works by the Ancient ing Foreign Minister Nikos outlined the importance of the Kotzias told reporters after ties Greece has nurtured, along Greek master at meeting top US officials that with key ally Cyprus, with Is - America supports Greece’s effort rael, Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan Princeton Univ. Art to get debt relief from its inter - and the Palestinian authority, national creditors and discussed the report said. TNH Staff its’ role as a potential Mediter - He also referred to efforts to ranean hub and wanted calming boost ties with Armenia and PRINCETON, NJ – A major in - of provocations from Turkey Georgia. ternational exhibition of classi - over the Aegean. The collapsed United Na - cal Greek vases opened on During his two-day trip to tions-backed Cyprus unity talks March 4 at the Princeton Uni - the US, Kotzias portrayed cash- were also raised, with Kotzias versity Art Museum. The Berlin crunched Greece, in the depths saying it was because of Painter and His World: Athenian of a seven-year economic crisis, Turkey’s insistence on keeping Vase-Painting in the Early Fifth as nonetheless a stable partner an army and military interven - Century BC runs through June in the volatile Balkans and tion rights over the island di - 11 and “is a celebration of an - prospects for being a conduit for vided since an unlawful inva - cient Greece and of the ideals energy from the Middle East, sion in 1974. -

The Colonels' Dictatorship and Its Afterlives

This is a postprint version of the following published document: Antoniou, D., Kornetis, K., Sichani, A.M. and Stefatos, K. (2017). Introduction: The Colonels' Dictatorship and Its Afterlives. Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 35(2) pp. 281-306. DOI: 10.1353/mgs.2017.0021 © 2017 by The Modern Greek Studies Association Introduction: The Colonels’ Dictatorship and Its Afterlives Dimitris Antoniou, Kostis Kornetis, Anna-Maria Sichani, and Katerina Stefatos A half century after the coup d’état of 21 April 1967, the art exhibition docu- menta 14 launched its public programs in Athens by revisiting the Colonels’ dictatorship. The organizers chose the former headquarters of the infamous military police (EAT/ESA) to host the “exercises of freedom,”1 a series of walk- ing tours, lectures, screenings, and performances that examined resistance, torture, trauma, and displacement in a comparative perspective. The initia- tive was met with mixed feelings, and its public discussion raised import- ant questions about the past. Why is it urgent today to revisit the junta as a period of acute trauma? Can we trace the roots of Greece’s current predicament to its non-democratic past? What remains unsaid and unsayable about the dictatorship and its enduring legacies?2 While the junta has been a favorite subject for public history (broadly understood here to include literature, film, personal testimonies, and so on), research on it has remained on the margins. Initially, it was marked by sporadic attempts to respond to the pressing public interest to understand the dictator- ship as a contemporary phenomenon (Tsoucalas 1969; Clogg and Yannopoulos 1972; Poulantzas 1976; Mouzelis 1978) and, most importantly, to explain how the Colonels came to power and why they managed to govern Greece for seven years. -

Abstract Book Rk4bw

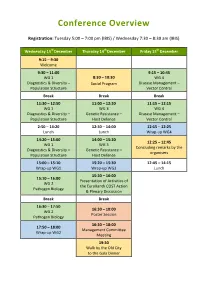

Conference Overview Registration: Tuesday 5:00 – 7:00 pm (IBIS) / Wednesday 7:30 – 8:30 am (IBIS) Wednesday 13rd December Thursday 14th December Friday 15th December 9:15 – 9:30 Welcome 9:30 – 11:00 9:15 – 10:45 WG 1 8:30 – 10:30 WG 4 Diagnostics & Diversity – Social Program Disease Management – Population Structure Vector Control Break Break Break 11:30 – 12:50 11:00 – 12:30 11:15 – 12:15 WG 1 WG 3 WG 4 Diagnostics & Diversity – Genetic Resistance – Disease Management – Population Structure Host Defence Vector Control 2:50 – 14:20 12:30 – 14:00 12:15 – 12:25 Lunch Lunch Wrap-up WG4 14:20 – 15:00 14:00 – 15:20 12:25 – 12:45 WG 1 WG 3 Concluding remarks by the Diagnostics & Diversity – Genetic Resistance – organisers Population Structure Host Defence 15:00 – 15:10 15:20 – 15:30 12:45 – 14:15 Wrap-up WG1 Wrap-up WG3 Lunch 15:30 – 16:00 15:10 – 16:00 Presentation of Activities of WG 2 the EuroXanth COST Action Pathogen Biology & Plenary Discussion Break Break 16:30 – 17:50 16:30 – 18:00 WG 2 Poster Session Pathogen Biology 16:30 – 18:00 17:50 – 18:00 Management Committee Wrap-up WG2 Meeting 19:30 Walk by the Old City to the Gala Dinner 1st Annual Conference of the EuroXanth COST Action Integrating Science on Xanthomonadaceae for integrated Plant disease management in EuroPe Organisers Joana Costa FitoLab – Instituto Pedro Nunes and University of Coimbra, Portugal Ralf Koebnik IRD, Montpellier, France Scientific Committee Jens Boch Leibniz University Hannover, Germany Vittoria Catara Wageningen University, The Netherlands Joana Costa University of Coimbra, Portugal Maria Leonor Cruz Instituto Nacional de Investigacao Agraria e Veterinaria, Oeiras, Portugal Ralf Koebnik IRD, Montpellier, France Tamas Kovacs ENVIROINVEST, Hungary Joël F. -

Management of Archival Literary Sources: the Greek Approach Marietta Minotos and Anna Koulikourdi

Management of archival literary sources: the Greek approach Marietta Minotos and Anna Koulikourdi In Greece, as in many other countries, literary archives play an important role in the intellectual, social, political and cultural life of the country and are interconnected with the history of the state. Since the phenomenon of the diaspora of literary archives is familiar to all literary researchers, the scope of this article is to promote awareness of literary archives in Greece and to provide an approach to literary sources in an exceptionally wide range of archival institutions. It takes into account the Greek historical background in literary traditions and connects it with the current intensive interest in the archives, the legal framework, the principles of access to archival material and the challenges of on-line access for this category of archives and archivists. Eternity is quality, not quantity, this is the big but very simple secret. Nikos Kazantzakis (1883–1957) Where and how is literary memory safeguarded in Greece? The purpose of this article is to answer this basic question, presenting a representative picture of Greek literary archives, the places in which they are located and the way they are organized, the mapping of the archival landscape in this field, the accessibility and finding aids of the archival material and the challenges set by new technologies in the digital era. The profile of literary archives Literary archives constitute a specialized category of archives and include all kinds of documents, items and testimonies in every format, which were produced and are related to the intellectual, personal and social activity of a litterateur. -

Polarization in Greek Politics: PASOK's First Four Years, 1981-1985 by STATHIS N

Polarization in Greek Politics: PASOK's First Four Years, 1981-1985 by STATHIS N. KALYVAS The victory of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) in 1981 was a crucial test for the young Greek democracy for at least two reasons. First, this new party, founded only seven years earlier in 1974, was up to 1977, a "semi-loyal" party (Diamandouros 1991) critical of the country's new institutions and of its general orientation. Even after 1977, and up to 1981, the party remained at best ambivalent about its fundamental foreign policy intentions. In the context of the Cold War, driving Greece out of NATO, as the party claimed it would do, was a prospect fraught with grave dangers for the country's regime. Second, this was the first instance of democratic alternation of power. After seven years in power, New Democracy (ND), the center-right party founded by Constantine Karamanlis, was soundly defeated. The importance of this can hardly be under- estimated, since the legacy of the Civil War still loomed large, and previous attempts of alternation in the mid-sixties had been blocked (including by the 1967 military coup). Indeed, PASOK claimed to represent precisely the political and social groups whose legitimate representation had been thwarted in the past. In short, 1981 was clearly going to test the degree to which the Greek democratic regime was really consolidated. The 1981 elections took place amid a highly polarized STATIIIS N. KALYVAS is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Department of Politics and the Onassis Center at New York Univer- sity and is author of The Rise of Christian Democracy in Europe (Cornell, 1996).