Port and the City: Balancing Growth and Liveability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore, July 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Singapore, July 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: SINGAPORE July 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Singapore (English-language name). Also, in other official languages: Republik Singapura (Malay), Xinjiapo Gongheguo― 新加坡共和国 (Chinese), and Cingkappãr Kudiyarasu (Tamil) சி க யரச. Short Form: Singapore. Click to Enlarge Image Term for Citizen(s): Singaporean(s). Capital: Singapore. Major Cities: Singapore is a city-state. The city of Singapore is located on the south-central coast of the island of Singapore, but urbanization has taken over most of the territory of the island. Date of Independence: August 31, 1963, from Britain; August 9, 1965, from the Federation of Malaysia. National Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Lunar New Year (movable date in January or February); Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date in February); Good Friday (movable date in March or April); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (June 2); National Day or Independence Day (August 9); Deepavali (movable date in November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date according to the Islamic lunar calendar); and Christmas (December 25). Flag: Two equal horizontal bands of red (top) and white; a vertical white crescent (closed portion toward the hoist side), partially enclosing five white-point stars arranged in a circle, positioned near the hoist side of the red band. The red band symbolizes universal brotherhood and the equality of men; the white band, purity and virtue. The crescent moon represents Click to Enlarge Image a young nation on the rise, while the five stars stand for the ideals of democracy, peace, progress, justice, and equality. -

The Port of Singapore Authority : Competing in a Declining Asian Economy

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The port of Singapore authority : competing in a declining Asian economy Gordon, John; Tang, Hung Kei; Lee, Pui Mun; Henry, C. Lucas, Jr; Wright, Roger 2001 Gordon, J., Tang, H. K., Lee, P. M., Henry, C. L. Jr. & Wright, J. (2001). The Port of Singapore Authority: Competing in a Declining Asian Economy. Singapore: The Asian Business Case Centre, Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/100669 © 2001 Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, stored, transmitted, altered, reproduced or distributed in any form or medium whatsoever without the written consent of Nanyang Technological University. Downloaded on 03 Oct 2021 10:21:37 SGT AsiaCase.com the Asian Business Case Centre THE PORT OF SINGAPORE AUTHORITY: Publication No: ABCC-2001-003 COMPETING IN A DECLINING ASIAN ECONOMY Print copy version: 26 Nov 2001 Professors John Gordon, Tang Hung Kei, Pui Mun Lee, Henry C. Lucas, Jr. and Roger Wright, with assistance from Amy Hazeldine Eric Lui, Director of Information Technology (IT) and Executive Vice President of the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA) sat in his Alexandra Road offi ce in Singapore, worried about the future success of the port. PSA was feeling the impact of the declining regional economy and had also to manage the heightened competition both now and once the current crisis passed. “We have built one of the most effi cient and largest ports in the world, and yet we are subject to economic forces beyond our control,” he thought. -

The Enduring Ideas of Lee Kuan Yew

THE STRAITS TIMES By Invitation The enduring ideas of Lee Kuan Yew Kishore Mahbubani (mailto:[email protected]) PUBLISHED MAR 12, 2016, 5:00 AM SGT Integrity, institutions and independence - these are three ideas the writer hopes will endure for Singapore. March 23 will mark the first anniversary of the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew. On that day, the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy will be organising a forum, The Enduring Ideas of Lee Kuan Yew. The provost of NUS, Professor Tan Eng Chye, will open the forum. The four distinguished panellists will be Ambassador-at-Large Chan Heng Chee, Foreign Secretary of India S. Jaishankar, Dr Shashi Jayakumar and Mr Zainul Abidin Rasheed. This forum will undoubtedly produce a long list of enduring ideas, although only time will tell which ideas will really endure. History is unpredictable. It does not move in a straight line. Towards the end of their terms, leaders such as Mr Jawaharlal Nehru, Mr Ronald Reagan and Mrs Margaret Thatcher were heavily criticised. Yet, all three are acknowledged today to be among the great leaders of the 20th century. It is always difficult to anticipate the judgment of history. ST ILLUSTRATION : MIEL If I were to hazard a guess, I would suggest that three big ideas of Mr Lee that will stand the test of time are integrity, institutions and the independence of Singapore. I believe that these three ideas have been hardwired into the Singapore body politic and will last. INTEGRITY The culture of honesty and integrity that Mr Lee and his fellow founding fathers created is truly a major gift to Singapore. -

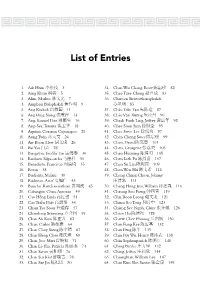

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Urban Tropical Ecology in Singapore Biology / Environ 571A

URBAN TROPICAL ECOLOGY IN SINGAPORE BIOLOGY / ENVIRON 571A Course Description (from Duke University Bulletin) Experiential field oriented course in Singapore and Malaysia focusing on human ecology, tropical diversity, disturbed habitats, Asian extinctions, and resource management. Students spend approximately three weeks in Singapore/Malaysia during the spring semester. Additional course fees apply. Faculty: Dr. Dan Rittschof, Dr. Tom Schultz General Description Singapore is a fascinating combination of biophysical, human and institutional ecology, tropical diversity, disturbed habitats, invasive species and built environments. Within the boundaries of the city state/island of Singapore one can go from patches of primary rain forest to housing estates for 4.8 million plus residents, industrial complexes, and a port that processes between 800 and 1000 ships a day. Singapore's land area grew from 581.5 km2 (224.5 sq mi) in the 1960s to 704 km2 (271.8 sq mi) today, and may grow by another 100 km² (38.6 sq mi) by 2030. Singapore includes thousands of introduced species, including a multicultural assemblage of human inhabitants. Singapore should be in the Guinness Book of World Records for its increase in relative country size due to reclamation, and for the degree of governmental planning and control for the lives of its citizens. It is within this biological and social context that this experiential field oriented seminar will be conducted. Students will experience how this city state functions, and how it has worked to maintain and enhance the quality of life of its citizens while intentionally and unintentionally radically modifying its environment, in the midst of the extremely complicated geopolitical situation of Southeast Asia. -

Chapter Two Marine Organisms

THE SINGAPORE BLUE PLAN 2018 EDITORS ZEEHAN JAAFAR DANWEI HUANG JANI THUAIBAH ISA TANZIL YAN XIANG OW NICHOLAS YAP PUBLISHED BY THE SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF BIOLOGY OCTOBER 2018 THE SINGAPORE BLUE PLAN 2018 PUBLISHER THE SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF BIOLOGY C/O NSSE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION 1 NANYANG WALK SINGAPORE 637616 CONTACT: [email protected] ISBN: 978-981-11-9018-6 COPYRIGHT © TEXT THE SINGAPORE INSTITUTE OF BIOLOGY COPYRIGHT © PHOTOGRAPHS AND FIGURES BY ORINGAL CONTRIBUTORS AS CREDITED DATE OF PUBLICATION: OCTOBER 2018 EDITED BY: Z. JAAFAR, D. HUANG, J.T.I. TANZIL, Y.X. OW, AND N. YAP COVER DESIGN BY: ABIGAYLE NG THE SINGAPORE BLUE PLAN 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The editorial team owes a deep gratitude to all contributors of The Singapore Blue Plan 2018 who have tirelessly volunteered their expertise and effort into this document. We are fortunate to receive the guidance and mentorship of Professor Leo Tan, Professor Chou Loke Ming, Professor Peter Ng, and Mr Francis Lim throughout the planning and preparation stages of The Blue Plan 2018. We are indebted to Dr. Serena Teo, Ms Ria Tan and Dr Neo Mei Lin who have made edits that improved the earlier drafts of this document. We are grateful to contributors of photographs: Heng Pei Yan, the Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey photography team, Ria Tan, Sudhanshi Jain, Randolph Quek, Theresa Su, Oh Ren Min, Neo Mei Lin, Abraham Matthew, Rene Ong, van Heurn FC, Lim Swee Cheng, Tran Anh Duc, and Zarina Zainul. We thank The Singapore Institute of Biology for publishing and printing the The Singapore Blue Plan 2018. -

Harbourfront Station (CC29)(NE1) Train Service Has Been Affected and We Are Working to Restore Normal Service As Quickly As Possible

HarbourFront Station (CC29)(NE1) Train service has been affected and we are working to restore normal service as quickly as possible. We apologise for any inconvenience caused. Alternative Transport Bus Services from HarbourFront Station to: Aljunied Station (EW9) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 80 Bartley Station (CC12) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 93 Boon Keng Station (NE9) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 65 Bras Basah Station (CC2) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 124 Bugis Station (EW12)(DT14) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 80 Bukit Panjang Station (BP6)(DT1) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 963, 963E Cashew Station (DT2) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 963 Chinatown Station (NE4)(DT19) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 80, 124 Choa Chu Kang Station (NS4)(BP1) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 188 City Hall Station (NS25)(EW13) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 124 Clarke Quay Station (NE5) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 80, 124 Commonwealth Station (EW20) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 855 Dhoby Ghaut Station # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 65, 124 (NS24)(NE6)(CC1) Eunos Station (EW7) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 93 Farrer Park Station (NE8) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 65 Farrer Road Station (CC20) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 93, 855 Haw Par Villa Station (CC25) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 188 Hillview Station (DT3) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 963 Hougang Station (NE14) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 80 Kallang Station (EW10) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 80 Kent Ridge Station (CC24) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 963, 963E Khatib Station (NS14) # Bus Interchange (Exit A): 855 Kovan Station -

Hotel Address Postal Code 3D Harmony Hostel 23/25A Mayo

Changi Airport Transfer Hotel Address Postal Code 3D Harmony Hostel 23/25A Mayo Street S(208308) 30 Bencoolen Hotel 30 Bencoolen St S(189621) 5 Footway Inn Project Chinatown 2 227 South Bridge Road S(058776) 5 Footway Inn Project Ann Siang 267 South Bridge Road S(058816) 5 Footway Inn Project Chinatown 1 63 Pagoda St S(059222) 5 Footway Inn Project Bugis 8,10,12 Aliwal Street S(199903) 5 Footway Inn Project Boat Quay 76 Boat Quay S(049864) 7 Wonder Capsule Hostel 257 Jalan Besar S(208930) 38 Hongkong Street Hostel 38A Hong Kong Street S(059677) 60's Hostel 569 Serangoon Road S(218184) 60's Hostel 96A Lorong 27 Geylang S(388198) 165 Hotel 165 Kitchener Road S(208532) A Beary Best Hostel 16 & 18 Upper Cross Street S(059225) A Travellers Rest -Stop 5 Teck Lim Road S(088383) ABC Backpacker Hostel 3 Jalan Kubor (North Bridge Road) S(199201) ABC Premier Hostel 91A Owen Road S(218919) Adler Hostel 259 South Bridge Road S(058808) Adamson Inn Hotel 3 Jalan Pinang,Bugis S(199135) Adamson Lodge 6 Perak Road S(208127) Alis Nest Singapore 23 Robert Lane, Serangoon Road S(218302) Aliwal Park Hotel 77 / 79 Aliwal St. S(199948) Amara Hotel 165 Tanjong Pagar Road S(088539) Amaris Hotel 21 Middle Road S(188931) Ambassador Hotel 65-75 Desker Road S(209598) Amigo Hostel 55 Lavender Road S(338713) Amrise Hotel 112 Sims Avenue #01-01 S(387436) Amoy Hotel 76 Telok Ayer St S(048464) Andaz Singapore 5 Fraser Street S(189354) Aqueen Hotel Balestier 387 Balestier Road S(029795) Aqueen Hotel Lavender 139 Lavender St. -

![“S.S. KUALA” Researched Passenger List Sunk at Pom Pong Island 14 February 1942 [Version 6.8.0; April 2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8698/s-s-kuala-researched-passenger-list-sunk-at-pom-pong-island-14-february-1942-version-6-8-0-april-2017-418698.webp)

“S.S. KUALA” Researched Passenger List Sunk at Pom Pong Island 14 February 1942 [Version 6.8.0; April 2017]

“S.S. KUALA” Researched Passenger List Sunk at Pom Pong Island 14 February 1942 [Version 6.8.0; April 2017] Preface: This list and document have been compiled as a memorial and out of empathy and respect to the women, children and men who lost their lives in that cruel attack by Japanese bombers on the small coastal ship, converted into an auxiliary vessel, “SS. Kuala” on 14 February 1942, twelve hours after it escaped from Singapore. This was the day before Singapore surrendered to the Japanese. Many of the women and children were killed on the ship itself, but even more by continued direct bombing and machine gunning of the sea by Japanese bombers whilst they were desperately trying to swim the few hundred yards to safety on the shores of Pom Pong Island. Many others were swept away by the strong currents which are a feature around Pom Pong Island and, despite surviving for several days, only a handful made it to safety. The Captain of the “Kuala”, Lieutenant Caithness, recorded of the moment “…thirty men and women floated past on rafts and drifted east and then south – west, however only three survivors were picked up off a raft on the Indragiri River, a man and his wife and an army officer…”. The bombing continued even onto the Island itself as the survivors scrambled across slippery rocks and up the steep slopes of the jungle tangled hills of this small uninhabited island in the Indonesian Archipelago – once again, Caithness, recorded “…but when the struggling women were between the ships and the rocks the Jap had turned and deliberately bombed the women in the sea and those struggling on the rocks…”. -

Jurong Fishery Port (P

Jurong Fishery Port (p. 55) Jurong Railway (p. 56) Masjid Hasanah (p. 67) SAFTI (p. 51) Fishery Port Road A remaining track can be found at Ulu Pandan Park Connector, 492 Teban Gardens Road 500 Upper Jurong Road Established in 1969 at the former Tanjong Balai, this fishery between Clementi Ave 4 and 6 port handles most of the fish imported into Singapore and is also a marketing distribution centre for seafood. The Jurong Fishery Port and Market are open to public visits. Jurong Hill (p. 61) 1 Jurong Hill Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, the Singapore Opened in 1966, Jurong Railway was another means to Armed Forces Training Institute (SAFTI) was established to transport raw materials and export finished products from the provide formal training for officers to lead its armed forces. industrial estate. Operations ceased in the mid-1990s. Formerly located at Pasir Laba Camp, the institute moved to its current premises in 1995. Jurong’s brickworks industry and dragon kilns (p. 24) Following the resettlement of villagers from Jurong’s 85 Lorong Tawas (Thow Kwang Industry) and 97L Lorong Tawas surrounding islands in the 1960s, Masjid Hasanah was built Science Centre Singapore (p. 65) (Jalan Bahar Clay Studios), both off Jalan Bahar to replace the old suraus (small prayer houses) of the islands. 15 Science Centre Road With community support, the mosque was rebuilt and reopened in 1996. Nanyang University (p. 28) Currently the highest ground in Jurong, this hill provides a 12 Nanyang Drive (Library and Administration Building); vista of Jurong Industrial Estate. In the late 1960s, the hill was Yunnan Garden (Memorial); Jurong West Street 93 (Arch) transformed into a recreational space. -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

Singapore River

No tour of Singapore is complete without a leisurely trip along the Singapore River. More than any other waterway, the river has defined the island’s history as well as played a significant role in its commercial success. SKYSCRAPERS SEEN FROM SINGAPORE RIVER singapore river VICTORIA THEATRE & CONCERT HALL SUPREME COURT PADANG SINGAPORE RIVER SIR STAMFORD RAFFLES central 5 9 A great way to see the sights is to Kim, Robertson, Alkaff, book a river tour with the Clemenceau, Ord, Read, Singapore Explorer (Tel: 6339- Coleman, Elgin, Cavenagh, 6833). Begin your tour at Jiak Anderson and Esplanade — and Kim Jetty, just off Kim Seng in the process, pass through a Road, on either a bumboat (for significant slice of Singapore’s authenticity) or a glass-top boat history and a great many (for comfort). From here, you landmarks. will pass under 11 bridges — Jiak Robertson Quay is a quiet residential enclave that, in recent years, has seen the beginnings of a dining hub, with excellent restaurants and gourmet shops like La Stella, Saint Pierre, Coriander Leaf, Tamade and Epicurious, all within striking distance of each other. Close to the leafy coolness of Fort Canning as well as the jumping disco-stretch of Mohamed Sultan Road , the area offers a CLARKE QUAY more relaxed setting compared to its busier neighbour, Clarke Quay, downstream. With its vibrant and bustling concentration of pubs, seafood restaurants, street bazaars, live jazz bands, weekend flea markets and entertainment complexes, Clarke ROBERTSON QUAY Quay remains a magnet for tourists and locals. Restored in 1993, the sprawling village is open till late at night, filling the air with the warmth from the ROBERTSON QUAY CLARKE QUAY ROBERTSON QUAY/CLARKE QUAY charcoal braziers of the satay stalls (collectively called The Satay Club), the loud thump of discos and the general convivial air of relaxed bonhomie.