Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Joseph's, Bedford & Our Lady's, Kempston

St Joseph’s, Bedford & Our Lady’s, Kempston Parish Priest: Canon Seamus Keenan, Assistant Priest: Fr Roy Karakkattu MSFS The Presbytery, 2 Brereton Road, Bedford, MK40 1HU, Tel: 352569 www.stjosephsbedford.org Email: [email protected] Mass Times – St Joseph’s, Bedford PALM SUNDAY Sunday 8.15am May McKenna, RIP 20th March 2016 9.30am Francis Simmonds, RIP 11.00am People of the Parish 6.30pm James Foy, RIP Monday Holy Week 10.45am Eddy Haughey& Richard Breed Tuesday Holy Week 7.30am Joan Martin, RIP 10.45am Sherin Wednesday Holy Week 7:30am King Family (Special Intention) 10.45am Bridie Tolan Thursday Maundy Thursday-Mass of the Lord’s Supper 8.00pm Ben D’Souza, RIP Friday Good Friday 3.00pm Solemn Liturgy 7.30pm Stations of the Cross HOLY WEEK Saturday Holy Saturday-Easter Vigil 8.30pm People of the Parish Today begins the most solemn week in Mass Times – Our Lady’s, Kempston the Church’s year. The great events of Sunday 9.30am Maks Gregorec, RIP Our Lord’s redemptive work are Thursday 8.00pm O’Connor Family recalled and celebrated in the liturgies Good Friday 3.00pm Solemn Liturgy of Holy Week. Please make a special 7.30pm Stations of the Cross effort to attend all the liturgies of the Sacred Triduum, beginning on Maundy Confessions: Saturday 11.30am – 12.30pm Thursday evening and in particular the St Joseph’s: 5.00pm – 5.30pm Easter Vigil on Holy Saturday at 8.30pm. Please take a separate sheet RESPONSORIAL PSALM: from the back of the church detailing the My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? times of then Holy Week services. -

ST MARY CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL Woodside Way, Northampton, NN5 7HX

Catholic Diocese of Northampton INSPECTION REPORT OF DENOMINATIONAL CHARACTER AND RELIGIOUS EDUCATION (Under Section 48 of the Education Act 2005) ST MARY CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL Woodside Way, Northampton, NN5 7HX DfES School No: 928/3400 Head Teacher: Mrs P Turner Chair of Governors: Mr H Williams Reporting Inspector: Mr J Flanagan Associate Inspector: Mrs P Brannigan Date of Inspection: 1 July 2008 Date Report Issued: 14 July 2008 Date of previous Inspection: September 2006 The School is in the Trusteeship of the Diocese and in partnership with Northamptonshire Local Authority Description of the School St Mary’s is a smaller than average Catholic primary school with 151 pupils on roll. Since its last inspection, the school has changed in nature from a lower to a primary school and has, until recently, undergone a period of instability in leadership. 78% of the children live in areas identified as suffering from social deprivation and 41% of the children are baptised Catholics. Attainment on entry is below the national average and most children join the school after the Foundation Stage. 17 children have EAL and there are 29 on the SEN list. The school is not specifically linked to a parish but has links with St Patrick’s in Duston and Northampton Cathedral. Key Grades for Inspection 1: Outstanding 2: Good 3: Satisfactory 4: Unsatisfactory Overall Effectiveness of this Catholic School Grade 3 St Mary’s is a satisfactory school with a clear awareness of its Catholic mission and also of the areas for development. Relationships within the school are good and the care of the children is given a high priority. -

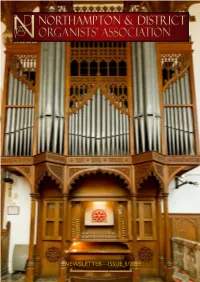

Newsletter—Issue 1/2019

NEWSLETTER—ISSUE 1/2019 FROM THE EDITOR May I wish all our members and friends a very happy New Year, and also take the opportunity to say a few words of introduction. It is my privilege to assume the editorship of our Newsletter, and I must begin by recording my sincere thanks to Barry for his excellent work over a number of years in producing the Newsletter, and for his most helpful handover to me. I am conscious that Barry’s work followed the equally high-quality journal which the late, and much-missed, Roger Smith produced for a decade. I will do all I can to uphold their standards and I hope you will continue to enjoy reading the Newsletter. Although work commitments have meant that it has been difficult for me to play a fuller part in the Association, I have been a member for more than 30 years, joining after a Carlo Curley concert at St Matthew’s in Northampton. I wonder how many of us remember those marvellous occasions? I am organist at St Mary Magdalene, Castle Ashby, and also play regularly at All Saints’ Earls Barton. You can read more about the Nicholson organ at Castle Ashby in this edition, and I will tell you more about the Earls Barton organ in the future. Two very different organs which demonstrate the variety of instruments in the county. As you would expect, you will find some changes in this edition of the Newsletter, both in format and content. I am very grateful to Barry, to Helen, and to Alan in smoothing the handover, and I hope you will like what you read. -

Pope Francis Proclaims 2021 As the “Year of St Joseph”

“Let us open the doors to the Spirit, let ourselves be guided by him, and allow God’s constant help to make us new men and women, inspired by the love of God which the Holy Spirit bestows on us. Amen” www.theucm.co.uk Spring 2021 Liverpool Metropolitan St Thomas Becket - Cathedral of Christ Reflection by Cardinal the King Vincent Nichols - Page 6 - Page 11 Pope Francis proclaims 2021 as the “Year of St Joseph” By Vatican News because “faith gives meaning to every event, however happy or sad,” In a new Apostolic Letter entitled Patris corde (“With a Father’s and makes us aware that “God can make flowers spring up from Heart”), Pope Francis describes Saint Joseph as a beloved stony ground.” Joseph “did not look for shortcuts but confronted reality father, a tender and loving father, an obedient father, an with open eyes and accepted personal responsibility for it.” For this accepting father; a father who is creatively courageous, a reason, “he encourages us to accept and welcome others as they are, working father, a father in the shadows. without exception, and to show special concern for the weak” (4). The Letter marks the 150th anniversary of Blessed Pope Pius IX’s A creatively courageous father, example of love declaration of St Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church. To Patris corde highlights “the creative courage” of St. Joseph, which celebrate the anniversary, Pope Francis has proclaimed a special “Year “emerges especially in the way we deal with difficulties.” “The of St Joseph,” beginning on the Solemnity of the Immaculate carpenter of Nazareth,” explains the Pope, was able to turn a problem Conception 2020 and extending to the same feast in 2021. -

Coidfoesec Gnatsaeailg

DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA YEARBOOK & CALENDAR 2017 £3.00 EastAnglia2017YearbookFrontSection_Layout 1 22/11/2016 11:29 Page 1 1 DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA (Province of Westminster) Charity No. 278742 Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Twinned with The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem and The Apostolic Prefecture of Battambang, Cambodia PATRONS OF THE DIOCESE Our Lady of Walsingham, 24th September St Edmund, 20th November St Felix, 8th March St Etheldreda, 23rd June BISHOP Rt Rev Alan Stephen Hopes BD AKC Bishop’s Residence: The White House, 21 Upgate, Poringland, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 7SH. Tel: (01508) 492202 Fax:(01508) 495358 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Cover Illustration: Bishop Alan Hopes has an audience with Pope Francis during a Diocesan pilgrimage to Rome in June 2016 EastAnglia2017YearbookFrontSection_Layout 1 22/11/2016 11:29 Page 2 2 Contents CONTENTS Bishop’s Foreword........................................................................................ 5 Diocese of East Anglia Contacts................................................................. 7 Key Diary Dates 2017.................................................................................. 14 Pope Francis................................................................................................ 15 Catholic Church in England and Wales..................................................... 15 Diocese of East Anglia................................................................................ 19 Departments...................................................................... -

CHURCHES TOGETHER in NORTHAMPTON Enarchhnolo MODERATOR CONTENTS Adina Curtis [email protected]

Churches Together Northampton CHURCHES TOGETHER IN NORTHAMPTON enarchhnolo MODERATOR CONTENTS Adina Curtis [email protected] uniting Churches of varied traditions, DEPUTY MODERATOR sharing information, action and prayer Rev David McConkey COMMENT FROM THE EDITOR 3 goVkaiologo [email protected] CHURCHES TOGETHER ENGLAND 4 SECRETARY Rev. Ted Hale CHURCHES TOGETHER N’PTON 6 [email protected] VhnproVtonqe 01604 7625305 DENOMINATIONAL 7 TREASURER CROSS/NON-DENOMINATIONAL 8 Mrs. Lesley Goulbourne [email protected] INDIVIDUAL CHURCH EVENTS Logos AND ORGANISATIONS 14 onkaiqeoVhn LOGOS EDITOR Joe Story NATIONAL/LOCALGOVERNMENT March 2015 [email protected] 01604 580478 AND VOLUNTARY SECTOR 18 TRAINING AND RESOURCES 21 ooologoV outoV CTN WEBSITE Hilary Tunbridge INTER-FAITH 25 Website address: JOBS AND VOLUNTEERING 26 www.churches-together- hnenarchpro northampton.org.uk LOGOS IS PRODUCED TEN TIMES A YEAR It is sent out by email free of charge or by post at cur- rent subscription charges. Vtonqeonpant Last date for copy is the 16th of the month preceding month of publication and anything for inclusion should be sent to the editor by that date, i.e. the 16th March for the April edition. LOGOS is the primary means of communication for adiautouege Churches together Northampton. Requests to pass on Items are included at the discretion of the information by email to churches instead of via editor based on policy agreed by Churches LOGOS will only be considered in exceptional and Together Northampton. netokaicwriV urgent circumstances. 3 4 COMMENT FROM THE EDITOR CHURCHES TOGETHER ENGLAND I would like to highlight an initiative in this month’s Logos. At the turn of the Millennium there was a large cross denomina- Churches Together in Peterborough and tional gathering in Abington Park over the Pentecost weekend. -

Arundel to Zabi Brian Plumb

Arundel to Zabi A Biographical Dictionary of the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales (Deceased) 1623-2000 Brian Plumb The North West Catholic History Society exists to promote interest in the Catholic history of the region. It publishes a journal of research and occasional publications, and organises conferences. The annual subscription is £15 (cheques should be made payable to North West Catholic History Society) and should be sent to The Treasurer North West Catholic History Society 11 Tower Hill Ormskirk Lancashire L39 2EE The illustration on the front cover is a from a print in the author’s collection of a portrait of Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman at the age of about forty-eight years from a miniature after an oil painting at Oscott by J. R. Herbert. Arundel to Zabi A Biographical Dictionary of the Catholic Bishops of England and Wales (Deceased) 1623-2000 Brian Plumb North West Catholic History Society Wigan 2006 First edition 1987 Second, revised edition 2006 The North West Catholic History Society 11 Tower Hill, Ormskirk, Lancashire, L39 2EE. Copyright Brian Plumb The right of Brian Plumb to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Printed by Liverpool Hope University ‘Some of them left a name behind them so that their praises are still sung, while others have left no memory. But here is a list of generous men whose good works have not been forgotten.’ (Ecclesiasticus 44. 8-10) This work is dedicated to Teresa Miller (1905-1992), of Warrington, whose R.E. -

Yearbook 2018

DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA YEARBOOK & CALENDAR 2018 £3.00 (-0#"- -&"%*/(*//07"5*0/-0$"--: '30.%&4,50145013*/5300.4 504)*#")"7&5)&%&7*$&45)"5 */$3&"4&130%6$5*7*5:"/%4"7&.0/&: 8&"-404611-:*/, 50/&3$0/46."#-&4 '03"/:.",&0'13*/5&303$01*&3 'PS'3&&JNQBSUJBMBEWJDFPSBDPNQFUJUJWFQSJDF JOGP!VOJRVFPGGJDFTZTUFNT XXXVOJRVFPGGJDFTZTUFNT )FBE0GåDF$IJHCPSPVHISPBE .BMEPO &TTFY $.3& 1 DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA (Province of Westminster) Charity No. 278742 Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Twinned with The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem and The Apostolic Prefecture of Battambang, Cambodia PATRONS OF THE DIOCESE Our Lady of Walsingham, September 24 St Edmund, November 20 St Felix, March 8 St Etheldreda, June 23 BISHOP Rt Rev Alan Stephen Hopes BD AKC Bishop’s Residence: The White House, 21 Upgate, Poringland, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 7SH. Tel: (01508) 492202 Fax:(01508) 495358 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Cover Illustration: Bishop Alan with children from Our Lady Star of the Sea in Lowestoft. 2 Contents CONTENTS Map of the Diocese of East Anglia............................................................. 4 Bishop Alan’s Foreword.............................................................................. 5 Diocese of East Anglia Contacts................................................................ 7 Key Diary Dates 2018.................................................................................. 14 Pope Francis................................................................................................ 15 Catholic Church in England and -

Saints & All Souls

The Catholic Parish of Saint Gregory the Great Northampton PART OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF NORTHAMPTON, REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER 234091 “A truly thriving Catholic community, OUR confidently and humbly proclaiming OUR VISION VISION the Good News of Jesus Christ.” All Saints & All Souls The 2015 James Bond film begins with an action sequence which In Aztec and Christian culture it is a celebration of life; of takes place in Mexico City on “Dia de Muertos” (The Day of the thanksgiving for the lives of those who have died and in prayer for Dead). There was a parade consisting of floats and people in them as they continue on the next part of their journey. The Mexican costumes of varying degrees of bad taste. people are insistent that is has absolutely NOTHING to do with the All this was fiction, there had been no “Day of the Dead” parade, Pagan “Hallowe’en” of North America and Britain. although there is a long tradition of commemorating this time of the However, the Dia de Muertos is, in fact a three-day celebration, year in a prayerful way. However, impressed by the carnival-like lasting from 31st October through to November 2nd, and for us too, procession in the film, the mayor of Mexico City organised a parade there are three days with significant events. As well as the in 2016 to mimic that in the film! celebrations of All Saints and All Souls, we have a Night of Light. The origin of the event goes back into pre-Christian times in Mexico, The usual Mass schedules of 7.00 am, 9.00 am and 7.00 pm will be where there was an Aztec celebration in the summer. -

Churches Together in Northampton - AGM - Minutes the Abbey Centre Chapel – Overslade Close – Northampton NN4 0RQ Sunday January 22Nd 2017 4.30 – 5.15 P.M

Churches Together in Northampton - AGM - Minutes The Abbey Centre Chapel – Overslade Close – Northampton NN4 0RQ Sunday January 22nd 2017 4.30 – 5.15 p.m. Amendments: IN the original minutes Appendix 3 should have been the Spiritual Well-being Report. This was sent out via the website Friday 27 th January following Niki Jenkins’ report of the error. Phyllis Thompson to be added to the apologies Jon & Crystal to be replaced in the enabling group by James Yates Opening Prayer – was offered by the Moderator, Adina Curtis, who then invited the meeting to share The Lord’s Prayer Apologies - Romeo Pedro, Colin Pye, David Chawmer, Jane Wade, George Sarmezy, James Yates, Gillian Craig, Vic Winchcombe, Alan Chesney, Gillian Craig, Aideen Fogarty. Attendees - 37 people signed an attendance sheet – see Appendix 1 for details . Minutes of AGM Tuesday January 24th 2016 (had been previously circulated) agreed nem com , Moderator’s Reflections: see Appendix 2 Treasurer's Report Annual subscription remains at £25 3 “New” churches joined CTN in 2016: Northampton Chinese Christian Church, Living Grace Church (change of name from Abington Christian Centre) and Redeemed Christian Church of God Note: The Northampton Chinese Evangelical Church decided to disband. The treasurer, Lesley Goulbourne, presented independently examined accounts; copies of which were available at the meeting. If anyone unable to attend wishes to receive a copy, please contact the secretary Other Reports Written reports were received by the secretary as follows: 3. Spiritual Wellbeing (NHS Trust). 4. Globe Project.. 5. Pitsford School & Army Cadet Force. 6. Northampton General Hospital. 7. Northamptonshire Association of Youth Clubs. -

22Nd Sunday OT Newsletter

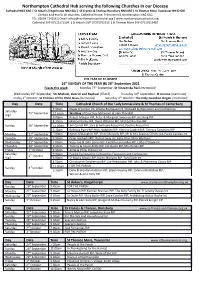

Northampton Cathedral Hub serving the following Churches in our Diocese Cathedral NN2 6AG | St Aidan’s Kingsthorpe NN2 6QJ | SS Francis & Therese Hunsbury NN4 0RZ | St Thomas More Towcester NN12 6JX Contact address for all churches: Cathedral House, Primrose Hill, Northampton NN2 6AG TEL: 01604 714556 | Email: [email protected] | www.northamptoncathedral.org Cathedral SVP 07515171104 | St Aidan’s SVP 07379752519 | St Thomas More SVP 07517613487 THE YEAR OF ST JOSEPH 26 th SUNDAY OF THE YEAR (B) 26 th September 2021 Feasts this week : Monday 27 th September: St Vincent de Paul (memorial) Wednesday 29 th September: Sts Michael, Gabriel and Raphael (FEAST) Thursday 30 th September: St Jerome (memorial) Friday 1 st October: St Thérèse of the Child Jesus (memorial) Saturday 2 nd October: The Holy Guardian Angels (memorial) Day Date Time Cathedral Church of Our Lady Immaculate & St Thomas of Canterbury 9.30am Nuala O’Connor Int, Amelia Rodriquez Int. followed by Exposition and Confessions Saturday 25 th September 12 noon Wedding of Courtney McKeown & Liam Thornhill Vigil 6.00pm Robert Morgan RIP, Peter & Margaret Sweeney RIP, Joe Borg RIP 8.30am Michael Earley RIP, Denis Williams RIP, Michael Riordan RIP Sunday 26 th September 11.00am Jim Carroll RIP, Sara & Anthony Russell Int, Pauline Russell Int 5.15pm Rebecca Parry RIP, Nick Hodgkins RIP, Vincent Cadden RIP, Terence Sammons RIP Monday 27 th September 7.00pm Agnes McLoughlin RIP, Vince Munnely RIP, Mr & Mrs Seamus O’Hara Int, Paraic Carolan Int Tuesday 28 th September 9.30am -

The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe Newsletter March 2014 Volume 1

The Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe Newsletter March 2014 Volume 1, Issue 2 Special events in our family’s life SPUC Newsletter • Add a highlight from It is with great sadness that we say farewell to Richard, the Shrine your family’s life Coordinator, who is leaving us following the completion of his one • Add a highlight from year sabbatical. your family’s life Contents: • Add a highlight from He has done sterling work in setting up the programme of visits to your family’s life Farewell Shrine Coordinator Cathedrals, churches and places of pilgrimage and has also been Team Guadalupe involved in the development of the lively and informative web site. Our past year National Pro-Life Mass We are working hard to find a replacement and have placed Luton Good Council advertisements in local church newsletters and the Catholic press. If anyone reading this newsletter is interested and would like Procession of Faith 2014 more information, please contact Dr Sue Sarsfield 01234 409739. National Partnership with the Knights of St Columba Team Guadalupe Home Shrine Devotion Andrew Hinde National Coordinator, Guardians of Relic of St Faustina visits The Our Lady of Guadalupe Shrine for Divine Mercy Mass Mary Frost Treasurer Teresa Williams Youth and Schools Development Coordinator Any donations will be Sue Sarsfield Media gratefully received by Anne Reddin Archives The Treasurer 4 Coniston Close Kempston Maggie Sloman Publications, graphics and designs MK42 8JT cheques payable to "OLOG” Thank you. The Shrine Newsletter Page 2 of 5 Our busy past year This year has been particularly busy for the Shrine Guardians as the Miraculous Relic Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe has been invited to various centres of worship on pilgrimage throughout England.