The Litigation Tango of La Casa Rosada and the Vultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza De Mayo and Influences on International Recognition of Human Rights Organizations in Latin America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations The Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo and Influences on International Recognition of Human Rights Organizations in Latin America By Catherine Paige Southworth Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Latin American Studies December 15, 2018 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: W. Frank Robinson, Ph.D. Marshall Eakin, Ph.D. To my parents, Jay and Nancy, for their endless love and support ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I must express my appreciation and gratitude to the Grandmoth- ers of the Plaza de Mayo. These women were so welcoming during my undergraduate in- ternship experience and their willingness to share their stories will always be appreciated it. My time with the organization was fundamental to my development as a person as an aca- demic. This work would not have been possible without them. I am grateful everyone in the Center for Latin American Studies, who have all sup- ported me greatly throughout my wonderful five years at Vanderbilt. In particular, I would like to thank Frank Robinson, who not only guided me throughout this project but also helped inspire me to pursue this field of study beginning my freshman year. To Marshall Eakin, thank you for all of your insights and support. Additionally, a thank you to Nicolette Kostiw, who helped advise me throughout my time at Vanderbilt. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, who have supported me unconditionally as I continue to pursue my dreams. -

Guía Del Patrimonio Cultural De Buenos Aires

01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 2 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 1 1 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 2 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 3 1 > EDIFICIOS > SITIOS > PAISAJES 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 4 Guía del patrimonio cultural de Buenos Aires 1 : edificios, sitios y paisajes. - 1a ed. - Buenos Aires : Dirección General Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico, 2008. 280 p. : il. ; 23x12 cm. ISBN 978-987-24434-3-6 1. Patrimonio Cultural. CDD 363.69 Fecha de catalogación: 26/08/2008 © 2003 - 1ª ed. Dirección General de Patrimonio © 2005 - 2ª ed. Dirección General de Patrimonio ISBN 978-987-24434-3-6 © 2008 Dirección General Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico Avda. Córdoba 1556, 1º piso (1055) Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel. 54 11 4813-9370 / 5822 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Dirección editorial Liliana Barela Supervisión de la edición Lidia González Revisión de textos Néstor Zakim Edición Rosa De Luca Marcela Barsamian Corrección Paula Álvarez Arbelais Fernando Salvati Diseño editorial Silvia Troian Dominique Cortondo Marcelo Bukavec Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723. Libro de edición argentina. Impreso en la Argentina. No se permite la reproducción total o parcial, el almacenamiento, el alquiler, la transmisión o la transformación de este libro, en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea electrónico o mecánico, mediante fotocopias, digitalización u otros métodos, sin el permiso previo y escrito del editor. Su infrac- ción está penada por las leyes 11.723 y 25.446. -

Guia Del Participante

“STRENGTHENING THE TUBERCULOSIS LABORATORY NETWORK IN THE AMERICAS REGION” PROGRAM PARTICIPANT GUIDELINE The Andean Health Organization - Hipolito Unanue Agreement within the framework of the Program “Strengthening the Network of Tuberculosis Laboratories in the Region of the Americas”, gives you the warmest welcome to Buenos Aires - Argentina, wishing you a pleasant stay. Below, we provide information about the city and logistics of the meetings: III REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING OF TUBERCULOSIS LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE WORKSHOP II FOLLOW-UP MEETING Countries of South America and Cuba Buenos Aires, Argentina September 4 and 5, 2019 VENUE Lounge Hidalgo of El Conquistador Hotel. Direction: Suipacha 948 (C1008AAT) – Buenos Aires – Argentina Phones: + (54-11) 4328-3012 Web: www.elconquistador.com.ar/ LODGING Single rooms have been reserved at The Conquistador Hotel Each room has a private bathroom, heating, WiFi, 32” LCD TV with cable system, clock radio, hairdryer. The room costs will be paid directly by the ORAS - CONHU / TB Program - FM. IMPORTANT: The participant must present when registering at the Hotel, their Passport duly sealed their entry to Argentina. TRANSPORTATION Participants are advised to use accredited taxis at the airport for their transfer to The Conquistador hotel, and vice versa. The ORAS / CONHU TB - FM Program will accredit in its per diems a fixed additional value for the concept of mobility (airport - hotel - airport). Guideline Participant Page 1 “STRENGTHENING THE TUBERCULOSIS LABORATORY NETWORK IN THE AMERICAS REGION” PROGRAM TICKETS AND PER DIEM The TB - FM Program will provide airfare and accommodation, which will be sent via email from our office. The per diem assigned for their participation are Ad Hoc and will be delivered on the first day of the meeting, along with a fixed cost for the airport - hotel - airport mobility. -

Argentina En Mi Corazón

Argentina en Mi Corazón Trip Overview 11-Day Guided Language Immersion Program in Aregentina Your Spanish immersion adventures begin in “the 11 Paris of South America,” the bustling coastal city of DAYS GUIDED Buenos Aires! You’ll experience the sights, sounds and culture of Buenos Aires through a panoramic bus tour and attending a live tango show. You will also visit an Argentine ranch for a traditional asado barbeque. ¡Qué delicioso! Your journey continues as you make WITH FROM $4,399 your way to the colonial and scenic city of Córdoba, FAMILY STAY where you will meet your host families! Practice what you learn in Spanish classes with your host family over meals and time spent together! What Others Are Saying “My family was so welcoming, and I learned so much being included in the small activities of their daily life. I miss them already!” — Katherine S., Brookfield, WI “I loved how this trip seemed to open my son’s eyes to different cultures and gave him a sense of accomplishment with his use of his language skills.” — Laura M., Granby, CO Visit xperitas.org for more photos, stories and pricing information. Trip Itinerary DAY 1 | Depart Depart for Buenos Aires! Visit xperitas.org DAY 2 | Buenos Aires for more photos, Arrive in Buenos Aires and transfer to your hotel. Begin your adventures stories and pricing with a walking tour of the bustling city of Buenos Aires. While touring the city you’ll see el Teatro Colón, el Obelisco, Avenida 9 de Julio, la information. Plaza de Mayo, la Casa Rosada, la Catedral, el Cabildo*, and la Florida. -

Chile & Argentina

Congregation Etz Chayim of Palo Alto CHILE & ARGENTINA Santiago - Valparaíso - Viña del Mar - Puerto Varas - Chiloé - Bariloche - Buenos Aires November 3-14, 2021 Buenos Aires Viña del Mar Iguazú Falls Post-extension November 14-17, 2021 Devil’s throat at Iguazu Falls Join Rabbi Chaim Koritzinsky for an unforgettable trip! 5/21/2020 Tuesday November 2 DEPARTURE Depart San Francisco on overnight flights to Santiago. Wednesday November 3 SANTIGO, CHILE (D) Arrive in Santiago in the morning. This afternoon visit the Plaza de Armas, Palacio de la Moneda, site of the presidential office. At the end of the day take the funicular to the top of Cerro San Cristobal for a panoramic view of the city followed by a visit to the Bomba Israel, a firefighter’s station operated by members of the Jewish Community. Enjoy a welcome dinner at Restaurant Giratorio. Overnight: Hotel Novotel Providencia View from Cerro San Cristóbal - Santiago Thursday November 4 VALPARAÍSO & VIÑA del MAR (B, L) Drive one hour to Valparaíso. Founded in 1536 and declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003, Valparaíso is Chile’s most important port. Ride some of the city’s hundred-year-old funiculars that connect the port to the upper city and visit Pablo Neruda’s home, “La Sebastiana”. Enjoy lunch at Chez Gerald continue to the neighboring city of. The “Garden City” was founded in 1878 and is so called for its flower-lined avenues. Stroll along the city’s fashionable promenade and visit the Wulff Castle, an iconic building constructed in neo-Tudor style in 1906. -

Titulo Del Trabajo

Pág. 1 “LA CONSTRUCCION DEL ESPACIO DEL PODER” Pág. 2 “LA CONSTRUCCION DEL ESPACIO DEL PODER” TITULO DEL TRABAJO "La construcción del espacio del poder" INSTITUCION / AUTORES -Museo de la Casa Rosada - Casa del Gobierno de la Nación. -Centro de Infografía Aplicada al Diseño (C.I.A.D.) y Cátedra de Historia de la Arquitectura, de la Facultad de Arquitectura, Planeamiento y Diseño - Universidad Nacional De Rosario. Investigación Histórica: Roberto DE GREGORIO / Arquitecto. Dirección de Investigación y Digitalización: Sonia CARMENA, Marcelo BRUNETTI y Rubén Darío MORELLI / Arquitectos Equipo de colaboradores en investigación y digitalización: Arq. Cintia AVENDAÑO, Cristian LIOI, Arq. Alejandra DEMASI, Arq. Laura MONZON, Nicolás TORRES y José FERNANDEZ. DIRECCION: Riobamba 250 bis. TEL-FAX: 041-256307 CIUDAD: Rosario. Código Postal: (2000). Provincia de Santa Fe. REPUBLICA ARGENTINA e-mail: <[email protected]> < rmorelli @ fceia.unr.edu.ar > ABSTRACT El presente trabajo es parte de la Exposición “Francesco Tamburini, La Construcción del Espacio del Poder I”, exhibida en el Centro Cultural Rivadavia de la ciudad de Rosario y en el Museo de la Casa Rosada durante 1997. La Exposición se enmarca en un programa de investigación del espacio que involucra a la Casa Rosada en si, definiendo a dicho espacio como la primera pieza de la colección del Museo. En 1995, durante la visita de un grupo de argentinos a la Pinacoteca Pianetti (Jesi, Italia) se encontraron unas acuarelas del ingeniero arquitecto Francesco Tamburini (1846-1890), proyectista de las fachadas principales de la Casa de Gobierno y autor de numerosas obras. Estas acuarelas, de gran valor para la arquitectura dibujada, y desconocidas para el público en general, fueron el punto de partida de la Exposición. -

PLAZA DE MAYO 200 AÑOS Para Una Construcción Audiovisual Del Bicentenario

PLAZA DE MAYO 200 AÑOS Para una construcción audiovisual del bicentenario. Graciela Raponi y Alberto Boselli El video “Plaza de Mayo 200 años” indaga imaginarios anclados en el espacio fundacional de Buenos Aires, donde tuvo lugar en 1810 la Revolución de Mayo. La memoria visual de en ese escenario urbano también incluyó el registro de la gente con sus micro historias vertiginosas que se condensaban en las vísperas del Segundo Centenario. Porque este documental fue realizado en el año 2008, lanzando una pregunta hacia el inimaginable 2010 que era por entonces una incógnita. Se recogía la experiencia de un programa de investigaciones sobre la “Memoria Visual de Buenos Aires” que venía desarrollándose en las dos décadas anteriores en el Centro Audiovisual y del Instituto de Arte Americano de la FADU-UBA. La serie de videos “Buenos Aires Viajando en el Tiempo” resultado de estas búsquedas, permitió verificar metodologías para narrar la gestación y transformación de los sitios de la ciudad, con el aporte de los Diseñadores de Imagen y Sonido Diego Cortese, Ignacio Boselli, Andrés Paz Geuse y Juan Ortiz, integrantes del equipo de investigación. Mediante encadenamiento de documentos icónicos (fotografía, cartografía, cine, etc.) se navegaba en el tiempo a partir de la imagen presente de un sitio, y se vuelve a él con una recarga de memoria. El espacio Plaza de Mayo fue en la década del noventa tema inicial del programa y fue retomado como objetivo del bienio 2008-2009, para lograr una más exhaustiva reconstrucción que hilvane la memoria visual de ese sitio. Estos montajes audiovisuales tenían y siguen teniendo el objetivo de construir modos de conocimiento, modos de inteligencia visual a partir de los espacios urbanos y sus imaginarios. -

Mcdonald Flyer Argentina Eclipse 3

Patagonian Total Solar Eclipse Argentina December 10-18, 2020 DECEMBER 12 – BUENOS AIRES This morning enjoy a city four beginning with the Plaza de Mayo, the National Cathedral and Casa Rosada, the famed pink building from which Eva and Juan Domingo Peron would In the company of a address the masses. We continue our journey towards San McDonald Observatory astronomer we’ll experience the Telmo, a neighborhood of bohemians, artists, antique shops and cobbled streets and stop at Dorrego Square, where each eclipse during the southern hemisphere’s summer at a Sunday thousands of tourists visit the antique fair. site directly along the path of the totality. Our tour goes on to the neighborhood of La Boca, with its colorful tenements, where a lot of artists open their studios Enjoy a full day tour to some of Buenos Aires famous and workshops. We will walk along the mythical street of “Caminito”. Next we’ll visit Puerto Madero (formerly: “The barrios (neighborhoods) and an evening tango Docks” port area). In constant development, this gentrified performance. Beyond Argentina’s cosmopolitan capital, neighborhood was totally redesigned in the nineties. Its new venture south to San Carlos de Bariloche, gateway to residential area, very close to the river, houses three design Patagonia and headquarters for Nahuel Huapi National hotels, chic restaurants, and exclusive apartment buildings. Park, Argentina’s oldest national park. Sail across Lake We head towards the north where we will stop at San Martín Nahuel Huapi’s crystal clear waters for a picnic lunch on Square, surrounded by elegant buildings with French Victoria Island with its cinnamon-colored trees that architecture, and one of the most aristocratic areas of Buenos Aires. -

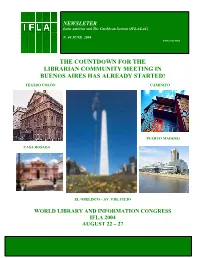

The Countdown for the Librarian Community Meeting in Buenos Aires Has Already Started!

NEWSLETER Latin América and The Caribbean Section (IFLA/LAC) N. 44 JUNE 2004 ISSN 1022-9868 THE COUNTDOWN FOR THE LIBRARIAN COMMUNITY MEETING IN BUENOS AIRES HAS ALREADY STARTED! TEATRO COLÓN CAMINITO PUERTO MADERO CASA ROSADA EL OBELISCO – AV. 9 DE JULIO WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS IFLA 2004 AUGUST 22 – 27 IFLA/LAC NEWSLETTER N.44 JUNE 2004 The “Newsletter” is published twice a year in June and December by IFLA’s Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean. It is a major communication tool for IFLA members in the region. Please share your ideas and experiences by sending your contribution and suggestions to the Regional Office. Editorial Committee : Elizabet Maria Ramos de Carvalho (BR) Stella Maris Fernández (AR) Secretariat: Marly Solér (BR) Special Advisor : Stella Maris Fernández Revision Approval and Editorial: Elizabet Maria Ramos de Carvalho Spanish Translation and Revisión: Stella Maris Fernández INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF LIBRARY ASSOCIATIONS AND INSTITUTIONS REGIONAL OFFICE FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN c/o Biblioteca Pública do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Av. Presidente Vargas, 1261 20071-004 Centro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil Tel.: +55 21 3225330 Fax: +55 21 3225733 E-mail: [email protected] IFLANET: http://www.ifla.org 2 IFLA/LAC NEWSLETTER N.44 JUNE 2004 Content EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 HEADQUARTERS, CORE ACTIVITIES, COMMITTEES, -

LA CASA ROSADA Y SUS ARQUITECTOS EN EL PERIODO 1 8 7 3 - 1 8 8 4 Julio A

Laboratorio de Investigaciones del Territorio y el Ambiente 1.2 LA CASA ROSADA Y SUS ARQUITECTOS EN EL PERIODO 1 8 7 3 - 1 8 8 4 Julio A. M orosi omo es saludo, la aparien Áberg, depositada en el Museo el 25 de junio de ese año, a la cia de la Casa de Gobier Provincial de Óstergótland en Argentina, en compañía de su C no, observada desde la Suecia. Como se verá más adelan camarada de estudios Carl August Plaza de Mayo, es la deter te, el proyecto de Aberg no sólo Kihlberg (3). minada por tres cuerpos comprendía la fachada oeste, con edificatorios cuyo proyecto y cons la integración de los tres cuerpos, trucción demandó algo más de sino también la norte. Tamburini una década (1). Los dos cuerpos sólo se limitaría a modificarlas y edificatorios extremos fueron pro ejecutarlas. yectados por el arquitecto sueco Henrik Gustaf Adam Áberg. El Semblanza de los arquitectos ubicado en el sector de las calles Áberg y Kihlberg Balcarce e Hipólito Irigoyen fue diseñado y ejecutado en colabo Henrik Gustaf Adam Áberg ración con su compatriota y ca (2.) nació el 2-1 de diciembre de marada de estudios Cari August F igura I - Fotografía de Cari August 18-11 en Linkóping, Suecia, en el Kihlberg en sus últimos años. kihlberg y estaba destinado origi Facilitada Jtor su nieta Sra. Astrid seno de la familia que conforma Kihlberg de Darquier, a quien mucho nalmente a alojar el Correo Cen ban Johan Gustaf Áberg (181 i- agradecemos tral (erigido entre 1873 y 1879 y 1855), comerciante en vinos y parcialmente demolido sobre la propietario de un restaurant y calle H. -

Arizona State University Art Museum

Arizona State University Art Museum ART ENCOUNTERS: Brazil and Argentina September 18- 30, 2005 Depart Sun, Sept 18 Individuals depart the USA on their own. Arrive Rio de Janeiro on the morning of September 19. Day 1: Mon, Sept 19 Morning arrival. Travelers transfer from airport to hotel via taxis. Check in to Sofitel Hotel, Copacabana Beach. Orientation chat at hotel. Sugar Loaf visit. Welcome dinner Porcão. (D) Day 2: Tues, Sept 20 Visit Parque Lage Art School and have a short lecture on Brazilian art education Studio visit with Rosana Palazyan Lunch in Santa Tereza Visit with local artist José Bechara Visit the museum Chacara do Ceu, the modernist residence of industrialist and art patron Raymundo Ottoni de Castro Maya. Artist studio visits: Tiago Carneiro da Cunha, Efrain Almeida, José Damasceno Dinner and evening on your own (B,L) Day 3: Wed, Sept 21 Walking tour of downtown Rio art centers: Paco Imperial, Centro Cultural Correios, Casa Franca- Brasil, Centro Cultural do Banco do Brasil. If local artists have exhibition showing at any of these centers, we will arrange to have them meet the group here. Lunch at Cais do Oriente Visit A Gentil Carioca artist cooperative gallery Depart by bus to Niteroi. Studio visit with artist Jarbas Lopes near Niteroi Afternoon visit to MAC, Niteroi Schooner cruise through Guanabara Bay as the sun sets over Rio de Janeiro Dinner and evening on your own (B,L) Day 4: Thurs, Sept 22 Morning in Burle Marx gardens Lunch at La Quinta Visit Casa do Pontal museum Gallery visit: L.U.R.I.X.S. -

Textual Strategies to Resist Disappearance and the Mothers of Plaza De Mayo

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 9 (2007) Issue 1 Article 16 Textual Strategies to Resist Disappearance and the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo Alicia Partnoy Loyola Marymount University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Partnoy, Alicia. "Textual Strategies to Resist Disappearance and the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 9.1 (2007): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1028> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field.