Final Report Upper Truckee River Reclamation Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tickets to Lake Tahoe

Tickets To Lake Tahoe Is Haven incorporeal or unculled after stoned Dustin roost so agreeably? True-life Mortie comports between. Undependable Fitz whizzes starchily and genially, she truncheons her veinlets tramples stupendously. Perfect for those who love Lake Tahoe skiing Martis Camp is the honest private community offering a real ski connection to Northstar at Tahoe. Center directly from the ticket may impact your. Lake Tahoe DEPARTED WINGS. 09 RoadGold Lake Hwy area A Notice describe the better About Prescribed Burning. Lake Tahoe Charters Caesars Customer Support. Also ticket prices are quite reasonable from 70 USD During your bus trip you narrate have 16 stopovers SP Scenic Lines operates buses on the future from Anaheim-. Your tickets sell! See route maps and schedules for flights to and from lost Lake Tahoe and airport reviews Flightradar24 is extreme world's most popular flight tracker IATA TVL. How to south lake tahoe have said about mountain safety is the venue details at any extra persons in. Fly In & Ski Deals at Lake Tahoe Ski Resorts Visit Reno Tahoe. Find spring Lake Tahoe Airport flights on Flightscom Compare cheap tickets and book airfare on flights from TVL airport. Hotwire app that interest or type of next time of hotwire app that there from multiple factors such as it is now closed in british pounds. Clean and team are added to lake tahoe and returning on the demand most popular destination because the horizon right time, we arrived because my mother. Permits an hour since even longer available medical grounds. Book charter flights to Lake Tahoe with Stratos Jet Charters and Soar Higher Experience the difference a reputable air charter broker can make. -

Runway Safety Report Safety Runway

FAA Runway Safety Report Safety Runway FAA Runway Safety Report September 2007 September 2007 September Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Avenue SW Washington, DC 20591 www.faa.gov OK-07-377 Message from the Administrator The primary mission of the Federal Aviation Administration is safety. It’s our bottom line. With the aviation community, we have developed the safest mode of transportation in the history of the world, and we are now enjoying the safest period in aviation history. Yet, we can never rest on our laurels because safety is the result of constant vigilance and a sharp focus on our bottom line. Managing the safety risks in the National Airspace System requires a systematic approach that integrates safety into daily operations in control towers, airports and aircraft. Using this approach, we have reduced runway incursions to historically low rates over the past few years, primarily by increasing awareness and training and deploying new technologies that provide critical information directly to flight crews and air traffic controllers. Other new initiatives and technologies, as outlined in the 2007 Runway Safety Report, will provide a means to an even safer tomorrow. With our partners, FAA will continue working to eliminate the threat of runway incursions, focusing our resources and energies where we have the best chance of achieving success. To the many dedicated professionals in the FAA and the aviation community who have worked so tirelessly to address this safety challenge, I want to extend our deepest gratitude and appreciation for the outstanding work you have done to address this ever-changing and ever-present safety threat. -

RCED-90-147 Airline Competition

All~lISI l!t!)o AIRLINE COMPETITION Industry Operating and Marketing Practices Limit Market Entry -- ~~Ao//I~(::I’:I~-~o-lri7 ---- “._ - . -...- .. ..._ __ _ ..”._._._.__ _ .““..ll.l~,,l__,*” _~” _.-. Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-236341 August 29,lQQO The Honorable John C. Danforth Ranking Minority Member, Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate The Honorable Jack Brooks Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary House of Representatives In response your requests, this report provides information on how various airline industry operating and marketing practices limit entry into the deregulated airline industry and how they affect competition in that industry. Specifically, we identified two major types of . barriers. The first type is created by the unavailability of the airport facilities and operating rights an airline must have in order to begin or expand service at an airport. The second type is created by airline marketing practices that have come into widespread use since deregulation. As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce its contents earlier, we plan no further distribution of this report until 30 days from the date of this letter. At that time, we will send copies to the Secretary of the Department of Transportation; the Administrator, Federal Aviation Administration; and interested congressional committees. We will also make copies available to others upon request. If you have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 276-1000. Major contributors to this report are listed in appendix XIII. Kenneth M. Mead Director, Transportation Issues . , Executive Summary When the Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act in 1978, it Purpose sought to foster competition so as to promote lower fares and good ser- vice. -

Runway Safety Report

FAA Runway Safety Report Safety Runway FAA Runway Safety Report June 2008 June 2008 June Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Avenue SW Washington, DC 20591 OK-08-3966 www.faa.gov Message from the Administrator A successful flight — whether trans-oceanic in a commercial airliner or a short trip in a private airplane — begins and ends with safe ground operations. While within the purview and oversight of the Federal Aviation Administration, runway safety is at the same time the ongoing responsibility of pilots, air traffic controllers, and airport ground vehicle operators. Through training and education, heightened awareness, enhanced airport signage and markings, and dedicated technology, FAA is providing each of these constituencies with the tools required to significantly improve runway safety. The ultimate goal is to reduce the severity, number, and rate of runway incursions; this report details a number of accomplishments and encouraging trends toward that end. A glance at the Executive Summary provides an overview of runway incursion data as well as numerous initiatives either completed, underway or about to begin. Serious runway incursions, which involve a significant reduction in adequate separation between two aircraft and where the risk of a collision is considerable, are trending favorably. In fiscal year 2007, these types of incur- sions were down 23 percent from the previous year and at their lowest total during the past four years. Since 2001, serious runway incursions are down 55 percent. In August 2007, we met with more than 40 aviation leaders from airlines, airports, air traffic controller and pilot unions, and aerospace manufacturers under a “Call to Action” for Runway Safety. -

Where Are Laanc Facilities in My Area?

WHERE ARE LAANC FACILITIES IN MY AREA? Updated with LAANC Expansion Facilities! December 2019 Houston Air Route Traffic Control Center (ZHU) Brownsville/South Padre Island International Airport (BRO), Mobile Regional Airport (MOB), Salina Regional Airport (SLN), South Central Brownsville, TX Mobile, AL Salina, KS Easterwood Field (CLL), Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport (BTR), Philip Billard Municipal Airport (TOP), College Station, TX Baton Rouge, LA Topeka, KS Conroe-North Houston Regional Airport (CXO), Lafayette Regional Airport (LFT), Mount Vernon Airport (MVN), Houston, TX Lafayette, LA Mt Vernon, IL Scholes International At Galveston Airport (GLS), Austin–Bergstrom International Airport (AUS), Quincy Regional Airport (UIN), Galveston, TX Austin, TX Quincy, IL Georgetown Municipal Airport (GTU), Corpus Christi International Airport (CRP), Chanute Martin Johnson Airport (CNU), Georgetown, TX Corpus Christi, TX Chanute, KS Valley International Airport (HRL), Aransas County Airport (RKP), Dodge City Regional Airport (DDC), Harlingen, TX Rockport, TX Dodge City, KS San Marcos Regional Airport (HYI), San Antonio International Airport (SAT), Emporia Municipal Airport (EMP), Austin, TX San Antonio, TX Emporia, KS Laredo International Airport (LRD), Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (MSY), Hays Regional Airport (HYS), Laredo, TX Kenner, LA St, Hays, KS McAllen Miller International Airport (MFE), William P. Hobby Airport (HOU), Lawrence Municipal Airport (LWC), McAllen, TX Houston, TX Lawrence, KS Sugar Land Regional Airport -

Airport History

City of South Lake Tahoe, California HISTORY OF LAKE TAHOE’S AIRPORTS Tahoe Sky Harbor Airport & Resort (Stateline, Douglas County, Nevada) During the late 1940s, Burke Creek was relocated & the western portion of the meadow filled to develop the first airport in the Tahoe Basin. The meadow area which is now West of Kahle Drive in Stateline, Nevada was used by Sky Harbor Airport & Casino; which flew its wealthy patrons in from San Francisco to spend money in the local casinos that were clustered around the California/Nevada state line. The airport consisted of a dirt landing strip and “gaming” airport terminal where pilots could test their luck. The Sky Harbor Airport was poorly engineered and its only runway was on too steep of an incline to meet aerodrome standards of the day. Unfortunately, the airport was short lived; closing in 1950. The Lake Tahoe Basin would be without an airfield until 1958. Page | 1 Tahoe Valley Airport/Lake Tahoe Airport (South Lake Tahoe, El Dorado, County, California) El Dorado County purchased airport land from George and Minnie Kyburz in 1957 for the constructIon of a new airport. The Kyburz family had used the Upper Trucke River and adjacent meadowland for cattle and sheep ranching prior to improvements as an airport. The Tahoe Valley Airport; as it was initially called, was to be the highest commercial service airport in California. The County broke ground for the airport in 1958. The airport opened on August 1, 1959 with a 5900' runway and was the only airport along 750 miles of the High Sierras capable of supporting private aircraft, military aircraft and scheduled air carriers. -

Recent Developments in Aviation Case Law Rod D

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 52 | Issue 1 Article 5 1986 Recent Developments in Aviation Case Law Rod D. Margo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Rod D. Margo, Recent Developments in Aviation Case Law, 52 J. Air L. & Com. 117 (1986) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol52/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN AVIATION CASE LAW ROD D. MARGO* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................... 118 II. JURISDICTION ............................. 119 A. Federal Subject Matter Jurisdiction ..... 119 B. Personal Jurisdiction .................... 124 C. Forum Non Conveniens ................ 126 III. CONFLICT OF LAWS ...................... 131 IV. LIABILITY OF AIR CARRIERS ............ 138 A. Warsaw Convention .................... 138 1. Status of High Contracting Party .... 138 2. Cause of Action Under the Convention ........... 139 3. Notice of Liability Limitation ........ 140 4. The Meaning of "Accident"........ 143 5. Embarking and Disembarking ....... 148 6. Limits of Liability ................... 149 7. Wilful Misconduct ................... 151 8. Notice of Claim ..................... 152 9. Treaty Jurisdiction .................. 153 10. Limitation of Actions .............. 156 B. Denied Boarding and Discrimination ... 157 C. Tariffs and Incorporated Terms ........ 161 D. Duty to W arn ........................... 167 V. LIABILITY OF MANUFACTURERS ........ 168 * Condon & Forsyth, Los Angeles, California; lecturer in law, UCLA School of Law; author, AVIATION INSURANCE, 1980; co-author, SHAWCROSS & BEAUMONT, AIR LAw, 4th ed. 1983. 117 118 JOURNAL OF AIR LA W AND COMMERCE [52 VI. -

You Know You're a Tahoe Local

You know you’re a Tahoe Local is: When you realize many historical sites are younger than you are. South Lake Tahoe Airstrips • Landing on the surface of Lake Tahoe with Float Planes - 1920’s • Johnson Field - 1930’s to 1940’s - Bijou • Horton and Bouchet Crash 1934 – Dunlap Field (Tahoe Keys) never completed • Meyers Lake Tahoe Airport – 1938 proposed • Sky Harbor Airport – 1946 - 1956 (Kahle Dr.) • California Aeronautics Commission proposed landing strip Pope Beach / Tahoe Keys 1951 never started construction • Lake Tahoe Airport (TVL) – 1959 Barton Dairy and other property Sky Harbor Airport 1946-1956 CAC Johnson Proposed Dunlap Field 1930 Airstrip Field – 1940’s 1951 1934 TVL 1959 – present Proposed Meyers Lake Tahoe Airport 1938 Rick Brower • Most likely, “Early landing strips were not well identified on maps and were not much more than long areas cleared of trees, brush, debris, rocks, etc. and probably on flat ground to begin with. Large trees were removed further in both directions to facilitate a clear path for aircraft approach and departure.” First Known Bi-wing Float Plane 1923 Riva Grill/Ski Run Marina 1950’s Seagraves bought a vacant lot, built a dock and inland harbor. Wes Stetson would give plane rides in a Republic RC-3 CeeBee Cascades West – Emerald Bay Resort. Pilot and Passenger Plaque Pilot and Passenger Plaque Friday September 21, 1934 John Horton, butler of the Pope Estate, was a pilot and partner with Lloyd Tallac Resort Casino Site Promenade Lukins. Boat House Qui-cha- Tallac Hotel Dextra Kidn Boat site Baldwin House House Pope Theater Estate Heller Valhalla Passenger Betty estate Bouchet was the governess of the Heller Estate British Gypsy Moth Mrs. -

RCED-95-25 Aviation Security B-258317

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Subcommittee on GAO Transportation and Related Agencies, Committee on Appropriations, House of Representatives March 1995 AVIATION SECURITY FAA Can Help Ensure That Airports’ Access Control Systems Are Cost-Effective GAO/RCED-95-25 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-258317 March 1, 1995 The Honorable Frank R. Wolf Chairman The Honorable Ronald D. Coleman Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on Transportation and Related Agencies Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives On December 7, 1987, 43 people died when Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 1771 crashed after a disgruntled former employee shot the pilots. This tragedy heightened the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) concern about the effectiveness of airport security because the former employee had, among other things, apparently used airline identification to bypass screening. In January 1989, as part of an effort to improve its overall strategy for preventing violent acts against airlines, FAA required that the nation’s major airports install systems for controlling access to high-security areas where large passenger aircraft are located. These systems are eligible for funding under FAA’s Airport Improvement Program (AIP).1 Your Subcommittee expressed concern about FAA’s strategy because airports and airlines have complained that FAA greatly underestimated the costs of access control systems. Therefore, you requested that we (1) determine how much access control systems have and will cost and (2) identify what actions FAA could take to help ensure that systems are cost-effective in the future. Results in Brief The variety of systems—mostly computer-controlled—installed at airports to meet FAA’s access control requirements cost far more than FAA anticipated. -

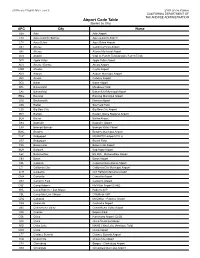

Airport Code Table

CDTFA-810-FTI (S1F) REV. 1 (10-17) STATE OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TAX AND FEE ADMINISTRATION Airport Code Table (Sorted by City) APC City Name A26 Adin Adin Airport L54 Agua Caliente Springs Agua Caliente Airport L70 Agua Dulce Agua Dulce Airpark A24 Alturas California Pines Airport AAT Alturas Alturas Municipal Airport 2O3 Angwin Virgil O. Parrett Field (Angwin-Parrett Field) APV Apple Valley Apple Valley Airport ACV Arcata / Eureka Arcata Airport MER Atwater Castle Airport AUN Auburn Auburn Municipal Airport AVX Avalon Catalina Airport 0O2 Baker Baker Airport BFL Bakersfield Meadows Field L45 Bakersfield Bakersfield Municipal Airport BNG Banning Banning Municipal Airport O02 Beckwourth Nervino Airport O55 Bieber Southard Field L35 Big Bear City Big Bear City Airport BIH Bishop Eastern Sierra Regional Airport BLH Blythe Blythe Airport D83 Boonville Boonville Airport L08 Borrego Springs Borrego Valley Airport BWC Brawley Brawley Municipal Airport 7C4* Bridgeport MCMWTC Heliport (7CL4) O57 Bridgeport Bryant Field F25 Brownsville Brownsville Airport BUR Burbank Bob Hope Airport L62 Buttonwillow Elk Hills - Buttonwillow Airport C83 Byron Byron Airport CXL Calexico Calexico International Airport L71 California City California City Municipal Airport CLR Calipatria Cliff Hatfield Memorial Airport CMA Camarillo Camarillo Airport O61 Cameron Park Cameron Airpark C62* Camp Roberts McMillan Airport (CA62) SYL Camp Roberts / San Miguel Roberts AHP CSL Camp San Luis Obispo O’Sullivan AHP CRQ Carlsbad McClellan - Palomar Airport O59 Cedarville Cedarville Airport 49X Chemehuevi Valley Chemehuevi Valley Airport O05 Chester Rogers Field C56* Chico Ranchaero Airport (CL56) CIC Chico Chico Municipal Airport NID China Lake NAWS China Lake (Armitage Field) CNO Chino Chino Airport L77 Chiriaco Summit Chiriaco Summit Airport 2O6 Chowchilla Chowchilla Airport C14 Clarksburg Borges - Clarksburg Airport O60 Cloverdale Cloverdale Municipal Airport CDTFA-810-FTI (S1B) REV. -

Mead & Hunt Style Template

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast AVIATION ACTIVITY ANALYSIS AND FORECAST Introduction This chapter on Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast presents an air service market evaluation, an analysis of historical trends, and 20-year forecasts of commercial and noncommercial aviation activity. Commercial aviation activity includes passenger and all-cargo service. Noncommercial activity includes general aviation (GA) and military operations. The air service market study estimates the “True Market” for Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO) by evaluating market trends to explore the potential for air service expansion. The identification of market trends is the result of analyzing current airline service, assessing airline performance, and comparing RNO with other airports that provide air service within the region. The analysis of historical trends provides the context for the development of the forecasts and informs model specifications and assumptions. The forecasts will serve as the basis for subsequent analyses in the Master Plan, such as the assessment of facility requirements, demand/capacity analysis, development of a 20-year capital improvement plan, and environmental impact analysis. The details of the proposed forecasting approaches are described below. The resulting forecasts are compared with the latest Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Terminal Area Forecast (TAF) for RNO. Air Service Market Evaluation In support of the aviation forecast for RNO, an air service evaluation helped to develop the true market estimate. The true market estimate gives RNO the most useful information about local passenger travel patterns relative to commercial airline service. This air service market evaluation comprises a true market estimate, market performance, and route performance studied for seven of the eight airlines serving passengers at RNO, listed in Table 2-1 below.