White Mou Ntain N Ational F Orest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Civil Works Program Fy 2020 Work Plan - Operation and Maintenance

ARMY CIVIL WORKS PROGRAM FY 2020 WORK PLAN - OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE STATEMENT OF STATEMENT OF ADDITIONAL LINE ITEM OF BUSINESS MANAGERS AND WORK STATE DIVISION PROJECT OR PROGRAM FY 2020 PBUD MANAGERS WORK PLAN ADDITIONAL FY2020 BUDGETED AMOUNT JUSTIFICATION FY 2020 ADDITIONAL FUNDING JUSTIFICATION PROGRAM PLAN TOTAL AMOUNT AMOUNT 1/ AMOUNT FUNDING 2/ 2/ Funds will be used for specific work activities including AK POD NHD ANCHORAGE HARBOR, AK $10,485,000 $9,685,000 $9,685,000 dredging. AK POD NHD AURORA HARBOR, AK $75,000 $0 Funds will be used for baling deck for debris removal; dam Funds will be used for commonly performed O&M work. outlet channel rock repairs; operations for recreation visitor ENS, FDRR, Funds will also be used for specific work activities including AK POD CHENA RIVER LAKES, AK $7,236,000 $7,236,000 $1,905,000 $9,141,000 6 assistance and public safety; south seepage collector channel; REC relocation of the debris baling area/construction of a baling asphalt roads repairs; and, improve seepage monitoring for deck ($1,800,000). Dam Safety Interim Risk Reduction measures. Funds will be used for specific work activities including AK POD NHS DILLINGHAM HARBOR, AK $875,000 $875,000 $875,000 dredging. Funds will be used for dredging environmental coordination AK POD NHS ELFIN COVE, AK $0 $0 $75,000 $75,000 5 and plans and specifications. Funds will be used for specific work activities including AK POD NHD HOMER HARBOR, AK $615,000 $615,000 $615,000 dredging. Funds are being used to inspect Federally constructed and locally maintained flood risk management projects with an emphasis on approximately 11,750 of Federally authorized AK POD FDRR INSPECTION OF COMPLETED WORKS, AK 3/ $200,000 $200,000 and locally maintained levee systems. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

New Hampshire River Protection and Energy Development Project Final

..... ~ • ••. "'-" .... - , ... =-· : ·: .• .,,./.. ,.• •.... · .. ~=·: ·~ ·:·r:. · · :_ J · :- .. · .... - • N:·E·. ·w··. .· H: ·AM·.-·. "p• . ·s;. ~:H·1· ··RE.;·.· . ·,;<::)::_) •, ·~•.'.'."'~._;...... · ..., ' ...· . , ·....... ' · .. , -. ' .., .- .. ·.~ ···•: ':.,.." ·~,.· 1:·:,//:,:: ,::, ·: :;,:. .:. /~-':. ·,_. •-': }·; >: .. :. ' ::,· ;(:·:· '5: ,:: ·>"·.:'. :- .·.. :.. ·.·.···.•. '.1.. ·.•·.·. ·.··.:.:._.._ ·..:· _, .... · -RIVER~-PR.OT-E,CT.10-N--AND . ·,,:·_.. ·•.,·• -~-.-.. :. ·. .. :: :·: .. _.. .· ·<··~-,: :-:··•:;·: ::··· ._ _;· , . ·ENER(3Y~EVELOP~.ENT.PROJ~~T. 1 .. .. .. .. i 1·· . ·. _:_. ~- FINAL REPORT··. .. : .. \j . :.> ·;' .'·' ··.·.· ·/··,. /-. '.'_\:: ..:· ..:"i•;. ·.. :-·: :···0:. ·;, - ·:··•,. ·/\·· :" ::;:·.-:'. J .. ;, . · · .. · · . ·: . Prepared by ~ . · . .-~- '·· )/i<·.(:'. '.·}, •.. --··.<. :{ .--. :o_:··.:"' .\.• .-:;: ,· :;:· ·_.:; ·< ·.<. (i'·. ;.: \ i:) ·::' .::··::i.:•.>\ I ··· ·. ··: · ..:_ · · New England ·Rtvers Center · ·. ··· r "., .f.·. ~ ..... .. ' . ~ "' .. ,:·1· ,; : ._.i ..... ... ; . .. ~- .. ·· .. -,• ~- • . .. r·· . , . : . L L 'I L t. ': ... r ........ ·.· . ---- - ,, ·· ·.·NE New England Rivers Center · !RC 3Jo,Shet ·Boston.Massachusetts 02108 - 117. 742-4134 NEW HAMPSHIRE RIVER PRO'l'ECTION J\ND ENERGY !)EVELOPMENT PBOJECT . -· . .. .. .. .. ., ,· . ' ··- .. ... : . •• ••• \ ·* ... ' ,· FINAL. REPORT February 22, 1983 New·England.Rivers Center Staff: 'l'bomas B. Arnold Drew o·. Parkin f . ..... - - . • I -1- . TABLE OF CONTENTS. ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS . ~ . • • . .. • .ii EXECUTIVE -

Atlantic Salmon Fry Stocking Schedule for New Hampshire in Spring 2006 to Volunteer to Stock Fry in Southern New Hampshire, Cont

Atlantic Salmon Fry Stocking Schedule for New Hampshire in Spring 2006 To volunteer to stock fry in southern New Hampshire, contact: Gabe Gries, NHFG at 603-352-9669 To volunteer to stock fry elsewhere in the Connecticut River basin, contact the Connecticut River Coordinator’s Office at 413-548-9138 Date River Number Meeting Place Time Fry 4/28 Lower Mascoma River 29,300 KFC, Rt 12A (S) W. Lebanon 10 am Bloods Brook off exit 20 I89S 5/2 S Br Sugar 41,500 Dennison Lumber pull off, 9:30 am Gunnison Brook Rt10 Goshen 5/5 Sugar River 64,200 Kellyville Bridge pull off, 9 am Rt103 Newport 5/8 Minnewawa Brook 33,000 NHFG Offc, Keene 9 am 5/12 *Little Sugar River 26,000 Indian Shutters Restaurant, 9 am Rt12 Charletown 5/15 *Lower Warren Brook 17,600 Vilas Pool pull off, Rt 123A 10 am Mill Brook Alstead Thompson Brook 5/19 *S Br Ashuelot River 21,800 NHFG Offc, Keene 9 am Roaring Brook 5/22 *Cold River 113,000 Vilas Pool pull off, Rt 123A 9:30 am Alstead Atlantic Salmon Fry Stocking Schedule for New Hampshire in Spring 2006 To volunteer to stock fry in northern New Hampshire, contact Dianne Emerson, NHFG at 603-788-3164 Date River Number Meeting Place Time Fry 5/4 Ammonoosuc River 185,000 Call for details Call for times 5/6 Ammonoosuc River 83,600 5/10 Gale River 101,500 Israel River 5/11 Wild Ammonoosuc River 151,500 5/15 Nash Stream 30,500 Atlantic Salmon Fry Stocking Schedule for Massachusetts in Spring 2006 To volunteer to stock fry in MA, contact Caleb Slater, MAFW at 508-792-7270 ext 133 To volunteer to stock fry elsewhere in the Connecticut -

New England District Team Commemorates Surry Mountain Lake Dam's 75Th Anniversary by Ann Marie R

New England District team commemorates Surry Mountain Lake Dam's 75th anniversary By Ann Marie R. Harvie, USACE New England District For the last 75 years, Surry Mountain Lake Dam in Surry, New Hampshire has stood at the ready to protect New Hampshire residents from flooding. The District team members who operate the project held a 75th anniversary event on October 1 from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., to commemorate the opening of the dam. “Among the participants that came to the event was a gentleman that worked at Surry Dam in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s,” said Park Ranger Eric Chouinard. “He shared some of his stories and experiences with us.” During the event, Chouinard and Park Ranger Alicia Lacrosse each gave a presentation. “The first was a history presentation,” said Chouinard. “I discussed life in the small town of Surry before the dam’s construction, a brief overview of the history of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the highly important Flood Control Act of 1936 which paved the way for the construction of Surry Dam, the reasoning behind why the town of Surry was chosen as the location for a flood control dam as opposed to other locations in Cheshire County, a brief history with pictures of the flood of 1936 and the hurricane of 1938, which both contributed to the construction of the Surry Dam.” Chouinard’s presentation also featured many historical construction photos. A presentation on invasive plants was given by Lacrosse. “The invasive presentation identified many of the species of local interest, such as Glossy Buckthorn, Japanese Knotweed, Autumn Olive and Eurasian Milfoil,” said Chouinard. -

White Mountain National Forest TTY 603 466-2856 Cover: a Typical Northern Hardwood Stand in the Mill Brook Project Area

Mill Brook United States Department of Project Agriculture Forest Final Service Eastern Environmental Assessment Region Town of Stark Coos County, NH Prepared by the Androscoggin Ranger District November 2008 For Information Contact: Steve Bumps Androscoggin Ranger District 300 Glen Road Gorham, NH 03581 603 466-2713 Ext 227 White Mountain National Forest TTY 603 466-2856 Cover: A typical northern hardwood stand in the Mill Brook project area. This document is available in large print. Contact the Androscoggin Ranger District 603-466-2713 TTY 603-466-2856 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activi- ties on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on Recycled Paper Mill Brook Project — Environmental Assessment Contents Chapter 1: Purpose and Need......................................................5 1.0 Introduction...............................................................5 1.1 Purpose of the Action and Need for Change . .7 1.2 Decision to be Made .......................................................11 1.3 Public Involvement........................................................12 1.4 Issues . .13 1.5 Alternatives Considered but Not Analyzed in Detail ...........................14 Chapter 2. -

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records FALL 2016 Vol. 35, No. 3 IN HONOR OF Rob Woodward his issue of New Hampshire TBird Records with its color cover is sponsored by friends of Rob Woodward in appreciation of NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS all he’s done for birds and birders VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3 FALL 2016 in New Hampshire. Rob Woodward leading a field trip at MANAGING EDITOR the Birch Street Community Gardens Rebecca Suomala in Concord (10-8-2016) and counting 603-224-9909 X309, migrating nighthawks at the Capital [email protected] Commons Garage (8-18-2016, with a rainbow behind him). TEXT EDITOR Dan Hubbard In This Issue SEASON EDITORS Rob Woodward Tries to Leave New Hampshire Behind ...........................................................1 Eric Masterson, Spring Chad Witko, Summer Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2016 by Ben Griffith and Lauren Kras ................2 Winter Jim Sparrell/Katie Towler, Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2016 Update by Rob Woodward ..............................25 LAYOUT Fall 2016 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report by Iain MacLeod ...................................26 Kathy McBride Field Notes compiled by Kathryn Frieden and Rebecca Suomala PUBLICATION ASSISTANT Loon Freed From Fishing Line in Pittsburg by Tricia Lavallee ..........................................30 Kathryn Frieden Osprey vs. Bald Eagle by Fran Keenan .............................................................................31 -

Investigating Tradeoffs Between Flood Control and Ecological Flow Benefits in the Connecticut River Basin Jocelyn Anleitner

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Environmental & Water Resources Engineering Civil and Environmental Engineering Masters Projects 5-2014 Investigating Tradeoffs Between Flood Control And Ecological Flow Benefits in the Connecticut River Basin Jocelyn Anleitner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cee_ewre Part of the Environmental Engineering Commons Anleitner, Jocelyn, "Investigating Tradeoffs Between Flood Control And Ecological Flow Benefits in the onneC cticut River Basin" (2014). Environmental & Water Resources Engineering Masters Projects. 64. https://doi.org/10.7275/8vfa-s912 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil and Environmental Engineering at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental & Water Resources Engineering Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATING TRADEOFFS BETWEEN FLOOD CONTROL AND ECOLOGICAL FLOW BENEFITS IN THE CONNECTICUT RIVER BASIN A Master’s Project Presented By: Jocelyn Anleitner Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Engineering April 2014 INVESTIGATING TRADEOFFS BETWEEN FLOOD CONTROL AND ECOLOGICAL FLOW BENEFITS IN THE CONNECTICUT RIVER BASIN A Master's Project Presented by JOCELYN ANLEITNER Approved as to style and content by: ~~tor Civil and Environmental Engineering Department ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank The Nature Conservancy (TNC) for funding this work through the Connecticut River Project. This work would not have been possible without, not only their funding, but the support and expertise they have provided. -

Summer 2020 Traffic Count Locations

MUNICIPALITY LOCATION TYPE ALBANY NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) WEST OF BEAR NOTCH RD SINGLE TUBE COUNT ALBANY BEAR NOTCH RD NORTH OF KANCAMAGUS HWY DOUBLE TUBE COUNT ALBANY DRAKE HILL RD OVER CHOCORUA RIVER SINGLE TUBE COUNT ALBANY DUGWAY RD EAST OF NH 112 SINGLE TUBE COUNT ALBANY NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) OVER TWIN BROOK SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT US 302/NH 16 SOUTH OF HURRICANE MT RD AT CONWAY TL SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT US 302 (CRAWFORD NOTCH RD) EB AT STONY BROOK DOUBLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT US 302 (CRAWFORD NOTCH RD) WB AT STONY BROOK DOUBLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT ALBANY AVE AT STATE OF NH RR TRACKS SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT RIVER ST AT SACO RIVER SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT TOWN HALL RD EAST OF US 302/NH 16 SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT NH 16A OVER EAST BRANCH RIVER SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT BEAR NOTCH RD OVER DOUGLAS BROOK SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT FOSTER ST BRIDGE OVER BROOK SINGLE TUBE COUNT BARTLETT HURRICANE MOUNTAIN RD OVER HOYT BROOK SINGLE TUBE COUNT BATH US 302/NH 10 (RUM HILL RD) WEST OF NH 112 SINGLE TUBE COUNT BATH WEST BATH ROAD WEST OF STATE OF NH RR SINGLE TUBE COUNT BATH DODGE RD EAST OF PETTYBORO RD SINGLE TUBE COUNT BATH PORTER RD OVER AMMONOOSUC RIVER SINGLE TUBE COUNT BENTON TUNNEL STREAM RD OVER DAVIS BROOK SINGLE TUBE COUNT BERLIN SCHOOL ST NORTH OF MASON ST SINGLE TUBE COUNT BERLIN MOUNT FOREST ST EAST OF FIRST AVE SINGLE TUBE COUNT BERLIN EXCHANGE ST WEST OF PLEASANT ST SINGLE TUBE COUNT BERLIN YORK ST WEST OF PLEASANT ST SINGLE TUBE COUNT BERLIN MADISON AVE NORTH OF EMERY ST SINGLE TUBE COUNT BERLIN GRANITE ST BETWEEN -

Stocking Report, May 14, 2021

Week Ending May 14, 2021 Town Waterbody Acworth Cold River Alstead Cold River Amherst Souhegan River Andover Morey Pond Antrim North Branch Ashland Squam River Auburn Massabesic Lake Barnstead Big River Barnstead Crooked Run Barnstead Little River Barrington Nippo Brook Barrington Stonehouse Pond Bath Ammonoosuc River Bath Wild Ammonoosuc River Belmont Pout Pond Belmont Tioga River Benton Glencliff Home Pond Bethlehem Ammonoosuc River Bristol Newfound River Brookline Nissitissit River Brookline Spaulding Brook Campton Bog Pond Carroll Ammonoosuc River Columbia Fish Pond Concord Merrimack River Danbury Walker Brook Danbury Waukeena Lake Derry Hoods Pond Dorchester South Branch Baker River Dover Cocheco River Durham Lamprey River Week Ending May 14, 2021 Town Waterbody East Kingston York Brook Eaton Conway Lake Epping Lamprey River Errol Clear Stream Errol Kids Pond Exeter Exeter Reservoir Exeter Exeter River Exeter Little River Fitzwilliam Scott Brook Franconia Echo Lake Franconia Profile Lake Franklin Winnipesaukee River Gilford Gunstock River Gilsum Ashuelot River Goffstown Piscataquog River Gorham Peabody River Grafton Mill Brook Grafton Smith Brook Grafton Smith River Greenland Winnicut River Greenville Souhegan River Groton Cockermouth River Groton Spectacle Pond Hampton Batchelders Pond Hampton Taylor River Hampton Falls Winkley Brook Hebron Cockermouth River Hill Needle Shop Brook Hill Smith River Hillsborough Franklin Pierce Lake Kensington Great Brook Week Ending May 14, 2021 Town Waterbody Langdon Cold River Lee Lamprey River -

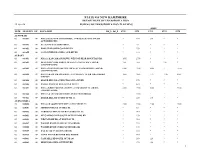

STATE of NEW HAMPSHIRE DEPARTMENT of TRANSPORTATION 19-Apr-04 BUREAU of TRANSPORTATION PLANNING AADT TYPE STATION FC LOCATION Int 1 Int 2 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 19-Apr-04 BUREAU OF TRANSPORTATION PLANNING AADT TYPE STATION FC LOCATION Int_1 Int_2 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 ACWORTH 82 001051 08 NH 123A EAST OF COLD RIVER (.75 MILES EAST OF SOUTH * 390 280 * * ACWORTH CTR) 82 001052 08 ALLEN RD AT LEMPSTER TL * 70 * * * 82 001053 09 FOREST RD OVER COLD RIVER * 190 * * * 82 001055 08 COLD RIVER RD OVER COLD RIVER * 110 * * * ALBANY 82 003051 07 NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) WEST OF BEAR MOUNTAIN RD 1500 2700 * * * 82 003052 07 BEAR NOTCH RD NORTH OF KANCAMAGUS HWY (SB/NB) 700 750 * 970 * (81003045-003046) 62 003053 02 NH 16 (CONTOOCOOK MTN HWY) AT TAMWORTH TL (SB/NB) 6200 7200 6600 * 7500 (61003047-003048) 02 003054 07 NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) AT CONWAY TL (EB-WB)(01003062- 1956 1685 1791 1715 2063 01003063) 82 003055 09 DRAKE HILL RD OVER CHOCORUA RIVER * 270 * * * 82 003056 08 PASSACONAWAY RD EAST OF NH 112 * 420 * * * 82 003058 02 NH 16 (WHITE MOUNTAIN HWY) AT MADISON TL (SB/NB) 8200 7500 6800 * 9300 (81003049-003050) 82 003060 07 NH 112 (KANCAMAGUS HWY) OVER TWIN BROOK * 2200 * * * 82 003061 09 DRAKE HILL RD SOUTH OF NH 16 * 120 140 * * ALEXANDRIA 22 005050 06 NH 104 (RAGGED MTN HWY) AT DANBURY TL 2300 2300 2100 * 2500 82 005051 09 SMITH RIVER RD AT HILL TL * 50 * * * 82 005052 08 CARDIGAN MOUNTAIN RD AT BRISTOL TL * 940 * * * 82 005053 09 MT CARDIGAN RD SOUTH OF WADHAMS RD * 130 * * * 82 005056 08 WEST SHORE RD AT BRISTOL TL * 720 * * * 82 005057 09 WASHBURN RD OVER PATTEN BROOK * 220 * * * 82 005058 08 WASHBURN RD OVER PATTEN BROOK * 430 * * * 82 -

Yankee Engineer Volume 41, No

Yankee Voices..................................2 Commander's Corner.....................3 Cape Cod Forrest Knowles...............................4 Patchogue Canal Joe Colucci retires............................5 River Rescues Dredging Up the Past......................8 Page 6 Page 7 US Army Corps of Engineers New England District Yankee Engineer Volume 41, No. 11 August 2006 Reservoirs too small, too shallow Corps of Engineers bans tube kiting at its federal recreation area lakes in New England for safety by Timothy Dugan safety of the public to ban the use of Middlebury (Route 63); Mansfield Public Affairs tube kites, or inflatable flying water- Hollow Lake in Mansfield (Route 6 or craft, at all Corps-managed federal Route 195); Northfield Brook Lake in The U.S. Army Corps of Engi- recreational projects in New England. Thomaston (Route 254); Thomaston neers, New England District issued a Federal projects managed by the Dam in Thomaston (Route 222); and ban as of July 28 on tube kiting at its 31 Corps are located in the following ar- West Thompson Lake in Thompson federal recreation flood control reser- eas. (Route 12). voir projects in New England. In Connecticut: Black Rock Lake In Massachusetts: Barre Falls Dam Signs will be posted detailing the in Thomaston (Route 109); Colebrook in Barre and Hubbardston (Route 62); prohibition. Most of the reservoirs are River Lake in Colebrook (Route 8); Birch Hill Dam in South Royalston too small and too shallow to support any Hancock Brook Lake in Plymouth (Route 68); Buffumville Lake in type of speed boating use. (Waterbury Road); Hop Brook Lake in Charlton (off Route 12); Cape Cod Of the seven lakes Canal in Buzzards Bay (I-195 where the Corps allows boat from Providence and Route 3 operation at speeds that from Boston); Charles River would support tube kites, the Natural Valley Storage Area lakes are not of sufficient in Eastern Massachusetts; size and depth to allow the Conant Brook Dam in Monson activity and ensure public (off Route 32 on Monson- safety.