HIV/AIDS a Humanitarian and Development Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unaids Programme Coordinating Board

UNAIDS PROGRAMME COORDINATING BOARD UNAIDS/PCB(33)/13.CRP5 Issue date: 10 December 2013 THIRTY-THIRD MEETING Date: 17-19 December 2013 Venue: Executive Board Room, WHO, Geneva Agenda item 9 PCB Submissions on Thematic Segment - HIV, Adolescents and Youth 1 Disclaimer: This compilation of submissions is for information only. With the exception of minor corrections to grammar and spelling, the submissions within this document are presented as they were submitted, and do not, implied or otherwise, express or suggest endorsement, a relationship with or support by UNAIDS and its mandate and/or any of its co-sponsors, Member States and civil society. The content of submissions has not been independently verified. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Nor does the content of the submissions necessarily represent the views of Member States, civil society, the UNAIDS Secretariat or the UNAIDS Cosponsors. The published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall UNAIDS be liable for damages arising from its use. UNAIDS expressly disclaims any responsibility for inadvertent offensive or insensitive, perceived or actual, language. 2 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………….……………………….……………. Page 9 I. Africa 104 submissions…………………………………………………………………………. Page 9 – 149 1. Algeria: Establishment of Three Animated Prevention Clubs against HIV in the Youth Community 2. -

Program Book

Program Book Page 1 Visit BD at Booth 105 BD MAX™ Vaginal Panel One clinician- or patient-collected vaginal swab provides results for the three most common causes of vaginitis – bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV)1. BD MAX Vaginal Panel detects DNA from In addition, BD MAX Vaginal Panel utilizes the the following BV markers: CDC-recommended diagnostic technology for T. vaginalis detection2 and provides three results for microorganisms responsible for Lactobacillus spp. yeast infections: G. vaginalis • group, including C. albicans, C. A. vaginae Candida L. jensenii parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. dubliniensis L. crispatus BVAB-2 Megasphaera-1 • Differentiates fungal species – C. glabrata Anaerobic spp. and C. krusei – associated with antimicrobial resistance3. The BD MAX™ Women’s Health and STI portfolio is focused on providing accurate, reliable results that enable clinicians and labs to elevate patient care. • BD MAX™ Vaginal Panel • BD MAX™ CT/GC/TV • BD MAX™ GBS Reference 1. BD MAX Vaginal Panel Package Insert 2. CDC (2015, June). MMWR Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. Mills, BB (2017) Vaginitis: Beyond the Basics. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 44(2):159-177. 3. Gaydos CA (2017) Clinical Validation of a Test for the Diagnosis of Vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 130(1):181-189. BD, the BD Logo and the BD MAX are trademarks of Becton, Dickinson and Company or its affiliates. © 2019 BD. All rights reserved. April 2019. Page 2 MAX MVP AD_5_5x8_5_GreenJournalAd_April.indd -

HIV and AIDS in Georgia: a Socio-Cultural Approach

HIV and AIDS in Georgia: A Socio-Cultural Approach The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views and official positions of UNESCO or of the Flemish government. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this review do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO or the Flemish government concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. This project has been supported by the Flemish government. Published by: Culture and Development Section Division of Cultural Policies and Intercultural Dialogue UNESCO 1, rue Miollis, 75015 Paris, FRANCE e-mail : [email protected] web site : www.unesco.org/culture/aids Project Coordination: Helena Drobná and Christoforos Mallouris Cover design and Typesetting: Gega Paksashvili Project Coordination UNESCO: CLT/CPD/CAD - Helena Drobna, Christoforos Mallouris Project Coordination Georgia: Foundation of Georgian Arts and Culture – Maka Dvalishvili Printed by “O.S.Design” UNESCO Number: CLT/CPD/CAD-05/4D © UNESCO 2005 CONTENTS Pages Forewords 4 Preface 6 Acknowledgements 8 List of acronyms 9 Map of Georgia 10 Part I. HIV and AIDS overview in Georgia Introduction 11 I.1 HIV epidemiology in Georgia 12 I.2 Surveillance 12 I.3 Some characteristics of the Georgian culture 15 I.4 Drug use in Georgia 16 I.4.1 Drug use and related risky behaviour 16 I.4.2 Risk factors for HIV among IDU population 17 -

UNAIDS PCB 44 PMR Regional Country Report REV2

Agenda item 7.1 UNAIDS/PCB (44)/19.12.rev2 UNIFIED BUDGET, RESULTS AND ACCOUNTABILITY FRAMEWORK (UBRAF) Performance Monitoring Report 2018 Regional and Country report 25-27 June 2019 | Geneva, Switzerland UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board Issue date: 27 June 2019 Additional documents for this item: i. UNAIDS Performance Monitoring Report 2018: Introduction (UNAIDS/PCB (44)/19.11) ii. UNAIDS Performance Monitoring Report 2018: Strategy Result Area and indicator report (UNAIDS/PCB (44)/19.13) iii. UNAIDS Performance Monitoring Report 2018: Organizational report (UNAIDS/PCB (44)/19.14) Action required at this meeting: the Programme Coordinating Board is invited to: 1. Take note of the performance monitoring report and of continued efforts to rationalize and strengthen reporting, in line with decisions of the Programme Coordinating Board, and based on experience and feedback on reporting; 2. Urge all constituencies to contribute to efforts to strengthen performance reporting and to use the UNAIDS annual performance monitoring reports to meet their reporting needs; 3. Request UNAIDS to continue to strengthen joint and collaborative action at country level, in line with the revised operating model of the Joint Programme and as part of UN reform efforts. Cost implications of decisions: none UNAIDS/PCB (44)/19.12.rev2 Page 3/104 CONTENTS ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... -

COMMUNICATING with ADOLESCENTS About AIDS

M ARCH 1 997 COMMUNICATING with ADOLESCENTS about AIDS EXPERIENCE from EASTERN and SO UTHERN AFRICA R UTH NOU ATI AND WAMBUI K IAI ' IONAL DEVELOPM ENT RESEAR CH CENTRE COMMUNICATING with ADOLESCENTS about AIDS EXPERIENCE from EASTERN and SOUTHERN AFRlCA RUTH NOUATI AND WAMBUI KIAI INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTRE Ottawa • Cairo • Dakar •Johannesburg • Montevideo Nairobi • New Delhi • Singapore Published by the International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500, Ottawa, ON, Canada KIG 3H9 March 1997 Legal deposit: 1st quarter 1997 National Library of Canada ISBN 0-88936-832-5 The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the International Development Research Centre. Unless otherwise stated, copyright for material in this report is held by the authors. Mention of a proprietary name does not constitute endorsement of the prod uct and is given only for information. A microfiche edition is available. The catalogue of IDRC Books may be consulted online. Gopher: gopher.idrc.ca Web: http://www.idrc.ca This book may be consulted online at http://www.idrc.ca/books/focus.html TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Chapter 2 STUDY OBJECTIVES AND RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 33 2.1 Study Objectives 33 2.2 Study Methodology 33 Chapter 3 RESULTS OF THE RAPID ASSESSMENT OF THE PROGRAMS TARGETING ADOLESCENTS AND YOUTHS. 43 3.1 Types of HIV/AIDS communication programs targeted at adolescents. 43 3.2 Summary of a rapid process evaluation of the programs that were visited. 44 3.3 Cultural considerations in HIV/AIDS prevention programs 50 3.4 Overview of HIV/AIDS behavioral programs targeted at adolescents. -

Priorities for Early Prevention in a High-Risk Environment

WORLD BANK WORKING PAPER NO. 68 HIV/AIDS in the Western Balkans Public Disclosure Authorized Priorities for Early Prevention in a High-Risk Environment Joana Godinho Nedim Jaganjac Dorothee Eckertz Adrian Renton Public Disclosure Authorized Thomas Novotny Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK WORLD BANK WORKING PAPER NO. 68 HIV/AIDS in the Western Balkans Priorities for Early Prevention in a High-Risk Environment Joana Godinho Nedim Jaganjac Dorothee Eckertz Adrian Renton Thomas Novotny Lisa Garbus THE WORLD BANK Washington, D.C. Copyright (c) 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First Printing: September 2005 printed on recycled paper 1 2 3 4 5 07 06 05 World Bank Working Papers are published to communicate the results of the Bank’s work to the development community with the least possible delay. The manuscript of this paper therefore has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formally-edited texts. Some sources cited in this paper may be informal documents that are not readily available. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. -

ICASA 2019 Abstract Book

Welcome Address /Allocution de Bienvenue Welcome address by ICASA President The International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa is once again here with us. It comes at a critical juncture when we hardly have any time left to actualize the bold ambition of ending AIDS by 2030. It also comes a year before the review of UNAIDS global 90-90-90 targets in 2020. True to its identity, the 2019 edition of the International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa promises to offer a strategic forum for Leaders, Activists, Scientists and the Community to engage and find solutions to our common health problems. The Conference will provide a platform to take stock of progress made towards achieving the 90-90-90 targets. It also offers us an opportunity to collectively reflect on Hepatitis, TB, Malaria, NCDs, emerging infections in Africa and the opportunities available for strengthening our health systems on the continent to tackle these diseases. Visionary leadership and collaboration have been central to the achievements made in the response to HIV and AIDS thus far in Africa and globally. ICASA 2019 provides us with opportunities to re-invigorate our African commitments as well as global solutions that will allow us pave the way for new and efficient innovations towards a generation without AIDS in Africa. The intersection of cutting-edge science, innovations, effective community models, funding dynamics and policy that will be provided by the conference is expected to contribute greatly to achieving an AIDS free Africa. As we share evidence and reflect on progress made, let us keep in mind that despite the availability of a widening array of effective HIV prevention tools and methods and massive scale-up of HIV treatment, domestic financing for the response remains sub-optimal. -

Is HIV Really the Cause of AIDS?

Is “HIV” Really the Cause of AIDS And Are There Really Only “A Few” Scientists Who Doubt This? Over 1,000 scientists, medical professionals, authors and academics are on record that the “HIV-causes-AIDS” theories, routinely reported to the public as if they were facts, are dubious to say the least. View the list “It’s not even probable, let alone scientifically proven, that HIV causes AIDS. If there is evidence that HIV causes AIDS, there should be scientific documents which either singly or collectively demonstrate that fact, at least with a high probability. There are no such documents.” Spin Magazine, Vol. 10 No.4, 1994 “The HIV-causes-AIDS theory is one hell of a mistake.” Foreword, “Inventing the AIDS Virus” “Years from now, people will find our acceptance of the HIV theory of AIDS as silly as we find those who excommunicated Galileo.” “Dancing Naked in the Mind Field,” 1998 “Where is the research that says HIV is the cause of AIDS? There are 10,000 people in the world now who specialize in HIV. None has any interest in the possibility HIV doesn’t cause AIDS because if it doesn’t, their expertise is useless.” “People keep asking me, ‘You mean you don’t believe that HIV causes AIDS?’ And I say, ‘Whether I believe it or not is irrelevant! I have no scientific evidence for it.’ I might believe in God, and He could have told me in a dream that HIV causes AIDS. But I wouldn’t stand up in front of scientists and say, ‘I believe HIV causes AIDS because God told me.’ I’d say, ‘I have papers here in hand and experiments that have been done that can be demonstrated to others.’ It’s not what somebody believes, it’s experimental proof that counts. -

CV Mimiaga08.01.14

Mimiaga, p.1 CURRICULUM VITAE Matthew James Mimiaga, ScD, MPH DATE PREPARED: 08/01/2014 Office Address Massachusetts General Hospital / Harvard Medical School Behavioral Medicine Service, Department of Psychiatry 1 Bowdoin Square, 7th floor Boston, MA 02114 MGH Phone: 617.724.4977 MGH Fax: 617.724.8690 Mobile : 617.901.9276 Email: [email protected] Place of Birth Los Angeles, CA Education 2001 B.S. Psychology and Biological California Sciences Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA 2003 M.P.H. Epidemiology/Biostatistics Boston University, and Behavioral Sciences School of Public Health, Boston, MA 2007 Sc.D. Major: Psychiatric Harvard School of Epidemiology, Minors: Public Health, Infectious / Chronic Disease Boston, MA Epidemiology and Biostatistics Pre-Doctoral 09/1999- Pre- HIV/AIDS The University of Training 08/2000 Doctoral California at San Research Francisco (UCSF) and Training the Center for AIDS Fellowship Prevention Studies (CAPS), San Francisco, CA Post-Doctoral 05/2007- Post- Behavioral Medicine Harvard Medical Training 04/2008 Doctoral (Primary Mentor: School and Fellowship Steven A. Safren, PhD) Massachusetts General Hospital, Behavioral Medicine (Department of Psychiatry), Boston, MA Mimiaga, p.2 Academic Appointments 2007-2008 Research Fellow Harvard Medical School 2008-2010 Instructor in Psychiatry Harvard Medical School 2009-2010 Instructor in Epidemiology Harvard School of Public Health 2010-2014 Assistant Professor of Psychiatry Harvard Medical School 2010-2014 Assistant Professor of Epidemiology -

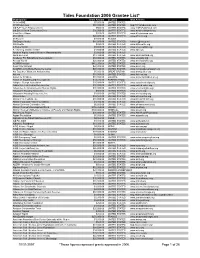

2006 Grantee List

Tides Foundation 2006 Grantee List* Organization Grant Amount Location Web Address 1+1+1=ONE $7,000.00 UNITED STATES 371 Productions $50,000.00 UNITED STATES http://371productions.com 3rd EyE Youth Empowerment $500.00 UNITED STATES www.3rdEyEunlimited.com 3rd Street Youth Center and Clinic $30,000.00 UNITED STATES www.bvhphealingarts.org 42nd Street Moon $100.00 UNITED STATES www.42ndstmoon.com 651 ARTS $40,000.00 UNITED STATES www.651arts.org 69 Parallel $9,000.00 RUSSIA 7th Empire Media $10,000.00 UNITED STATES [email protected] 826 Seattle $250.00 UNITED STATES www.826seattle.org A Home Within $5,000.00 UNITED STATES www.ahomewithin.org A Traveling Jewish Theater $1,600.00 UNITED STATES www.atjt.com Abortion Rights Fund of Western Massachusetts $2,500.00 UNITED STATES Abraham Fund $13,480.00 UNITED STATES www.abrahamfund.org Academy For Educational Development $10,000.00 UNITED STATES www.edequity.org Access Works $20,000.00 UNITED STATES www.accessworks.org ACORN Institute $412,250.00 UNITED STATES www.acorn.org Acorn International $20,000.00 UNITED STATES www.acorn.org ACORN Living Wage Resource Center $40,000.00 UNITED STATES www.livingwagecampaign.org Act Together: Women's Action in Iraq $5,000.00 GREAT BRITAIN www.acttogether.org Acterra $10,000.00 UNITED STATES www.Acterra.org Action for Children $10,000.00 UGANDA www.actionforchildren.or.ug Action on Disability and Development $24,426.00 BURKINA FASO Adaptive Design Association $25,000.00 UNITED STATES www.adaptivedesign.org Added Value & Herban Solutions Inc $20,000.00 UNITED STATES www.added-value.org Advocates for Environmental Human Rights $30,000.00 UNITED STATES www.ehumanrights.org/ Affordable Housing Associates $500.00 UNITED STATES www.ahainc.org Affordable Housing Resources, Inc. -

International AIDS Conference 2018

International AIDS Conference 2018 Asia-Pacific related sessions and activities 0 Contents Practical information ............................................................................................................ 2 Conference map .................................................................................................................... 3 Conference schedule ........................................................................................................... 4 Pre-Conferences.................................................................................................................... 5 Main Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 8 Satellite Sessions................................................................................................................ 17 Asia-Pacific epidemic profile ........................................................................................... 24 Key messages ...................................................................................................................... 27 1 Practical information Conference dates: 23-27 July 2018 Pre-conferences: 21-22 July 2018 Conference venue: RAI Amsterdam, Europaplein. NL 1078 GZ, Amsterdam Live stream (23 July): http://www.aids2018.org/Get-Involved/Join-us-virtually/AIDS- 2018-Live Conference objectives: 1. Convene the world’s experts to advance knowledge about HIV, present new research findings, and promote and enhance global scientific -

Program Book Table of Contents

Program Book Table of contents Welcome 3 Practical information 5 Organizing Committee 6 Fellows 6 Scientific Committee 7 Program 8 Capacity-building sessions 14 Symposiums 15 Faculty 17 Acknowledgments 35 Exhibitors 37 Notes 39 2 2 Asia-Pacific AIDS & Co-Infections Conference 2020 Program Book Welcome Dear Delegate, We are delighted to welcome you to the Asia-Pacific AIDS & Co-infections Conference (APACC) 2020, the first-ever virtual APACC. APACC provides a much-needed scientific platform that focuses on the developments, issues, and needs around HIV and co-infections in the Asia- Pacific region. Researchers have the opportunity to present and discuss Mark Boyd the latest developments and are provided with opportunities to interact, BA, BM, BS, DCTH&H, network, and form collaborations. Respected international experts integrate MHID, MD, FRACP science and clinical practice through state-of-the-art lectures, symposia, Lyell McEwin Hospital, and roundtable discussions in order to discuss best practices and advise on University of Adelaide, how treatment guidelines can be implemented. This year’s program features Australia plenary sessions, parallel sessions, capacity-building sessions, oral abstract presentations, poster presentations, virtual guided poster walks, and a virtual exhibition. This meeting offers a unique opportunity for regional clinicians, researchers, and representatives of the pharmaceutical industry to meet, learn, and share knowledge. We look forward to a productive and inspiring program. Patrick Chung-Ki Li Best regards, MBBS, FHKCP, FHKAM, FRCP Conference Chairs 2020 Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital, Hong Kong Nittaya Phanuphak MD, PhD Institute of HIV Research and Innovation, Thailand 3 Asia-Pacific AIDS & Co-Infections Conference 2020 Program Book Needs statement In the Asian-Pacific region, there are 5.9 million of people Among people living with HIV, there is also a high living with HIV.