University Micnxilms International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Actions 2/19/2020

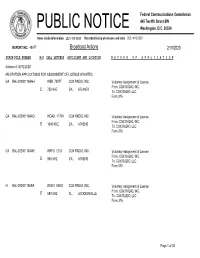

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49677 Broadcast Actions 2/19/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 02/12/2020 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED GA BAL-20200110AAH WSB 73977 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 750 KHZ GA ,ATLANTA To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 GA BAL-20200110AAQ WGAU 11709 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 1340 KHZ GA ,ATHENS To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 GA BAL-20200110AAR WRFC 1218 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 960 KHZ GA ,ATHENS To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 FL BAL-20200110ABA WOKV 53601 COX RADIO, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: COX RADIO, INC. E 690 KHZ FL , JACKSONVILLE To: COX RADIO, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 33 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49677 Broadcast Actions 2/19/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 02/12/2020 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED FL BAL-20200110ABI WDBO 48726 COX RADIO, INC. -

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission 445 12th St., S.W. News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 Internet: https://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 19-643 Released: July 11, 2019 MEDIA BUREAU ESTABLISHES PLEADING CYCLE FOR APPLICATIONS TO TRANSFER CONTROL OF COX RADIO, INC., TO TERRIER MEDIA BUYER, INC., AND PERMIT-BUT- DISCLOSE EX PARTE STATUS FOR THE PROCEEDING MB Docket No. 19-197 Petition to Deny Date: August 12, 2019 Opposition Date: August 22, 2019 Reply Date: August 29, 2019 On July 2, 2019, Terrier Media Buyer, Inc. (Terrier Media), Cox Radio, Inc. (Cox Radio), and Cox Enterprises, Inc. (Cox Parent) (jointly, the Applicants) filed applications with the Federal Communications Commission (Commission) seeking consent to the transfer of control of Commission licenses (Transfer Application). Applicants seek consent for Terrier Media to acquire control of Cox Radio’s 50 full-power AM and FM radio stations and associated FM translator and FM booster stations.1 As part of the proposed transaction, and in order to comply with the Commission’s local radio ownership rules,2 Cox has sought Commission consent to assign the licenses of Tampa market station WSUN(FM), Holiday, Florida, and Orlando market station WPYO(FM), Maitland, Florida, to CXR Radio, LLC, a divestiture trust created for the purpose of holding those stations’ licenses and other assets.3 1 A list of the Applications can be found in the Attachment to this Public Notice. Copies of the Applications are available in the Commission’s Consolidated Database System (CDBS). Pursuant to the proposed transaction, Terrier also is acquiring Cox’s national advertising representation business and Cox’s Washington, DC news bureau operation. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Orders TOC by Paragraph.Dot

Federal Communications Commission DA 19-1206 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Consent to Transfer Control of Certain License ) MB Docket No. 19-98 Subsidiaries of NBI Holdings, LLC to Terrier ) Media Buyer, Inc. ) File Nos. BTCCDT-20190304ABL et al. ) Consent to Transfer Control of Certain License ) File Nos. BTC-20190304ACS et al. Subsidiaries of Cox Enterprises, Inc. to Terrier ) Media Buyer, Inc. ) ) Consent to Assign Certain Licenses Held by Cox ) File Nos. BAL-20190304AER et al. Radio, Inc. to Camelot Radio Buyer, LLC ) ) Consent to Transfer Control of Certain License ) MB Docket No. 19-197 Subsidiaries of Cox Enterprises, Inc. to Terrier ) Media Buyer, Inc. ) File Nos. BTCH-20190702ABH et al. ) Consent to Assign Certain Licenses from Cox ) File Nos. BALH-20190702ADS et al. Radio, Inc. to CXR Radio, LLC ) ) File No. BALH-20190702ADV MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: November 22, 2019 Released: November 22, 2019 By the Chief, Media Bureau: I. INTRODUCTION 1. The Media Bureau (Bureau) has before it two interrelated sets of applications filed by substantially similar sets of parties in two separately docketed proceedings. In the first proceeding,1 Terrier Media Buyer, Inc. (Terrier Media), NBI Holdings, LLC (Northwest), and Cox Enterprises, Inc. (CEI) (jointly, the Television Applicants), seek consent to the transfer of control and assignment of Commission licenses through a pair of transactions. In one transaction, Terrier Media and Northwest seek consent for Terrier Media to acquire companies owned by Northwest holding the licenses of full- power broadcast television stations, low-power television (LPTV) stations, and TV translator stations (the Northwest Applications). -

US1 Distribution

1 US1 Distribution PR Newswire’s U.S. Distribution delivers your messages across the most trusted and comprehensive content distribution network in the industry, providing the broadest reach and sharpest targeting available. Business Alabama Monthly - Birmingham Bureau ALABAMA (Birmingham) Magazine Cherokee County Herald (Centre) Cullman Times (Cullman) Coastal Living Magazine (Birmingham) Decatur Daily (Decatur) Southern Living (Birmingham) Dothan Eagle (Dothan) Southern Breeze (Gulf Shores) Enterprise Ledger (Enterprise) Civil Air Patrol News (Maxwell AFB) Fairhope Courier (Fairhope) Business Alabama Monthly (Mobile) Courier Journal (Florence) Prime Montgomery (Montgomery) Florence Times Daily (Florence) Fabricating & Metalworking Magazine (Pinson) Times Daily (Florence) News Service Fort Payne Times-Journal (Fort Payne) Gadsden Times, The (Gadsden) Associated Press - Birmingham Bureau (Birmingham) Latino News (Gadsen) Associated Press - Mobile Bureau (Mobile) News-Herald (Geneva) Associated Press - Montgomery Bureau Huntsville Times, The (Huntsville) (Montgomery) Daily Mountain Eagle, The (Jasper) Newspaper Fairhope Courier, The (Mobile) Mobile Press-Register (Mobile) The Sand Mountain Reporter (Albertville) Montgomery Advertiser (Montgomery) The Outlook (Alexander) Opelika-Auburn News (Opelika) Anniston Star (Anniston) Pelican, The (Orange Beach) Athens News Courier (Athens) The Citizen of East Alabama (Phenix City) Atmore Advance (Atmore) Scottsboro Daily Sentinel (Scottsboro) Lee County Eagle, The (Auburn) Selma Times Journal (Selma) -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Attachment B

Attachment B Cox Enterprises, Inc. Atlanta, GA Broadcast TV: 15 Broadcast Radio: 81 Cable Channels: 7+ Cable Systems: 243 Newspapers: 9 Internet: 26+ Other: 3 Broadcast TV (15 ) Property Location WSB Atlanta, GA WSOC Charlotte, NC WHIO Dayton, OH WFTV Orlando, TV KIRO Seattle, WA KTVU San Francisco/Oakland, CA KICU San Jose/San Francisco, CA WRDQ Orlando, FL WPXI Pittsburgh, PA WAXN Charlotte, NC WJAC-TV Johnstown, PA KFOX-TV El Paso, TX KRXI Reno, NV KAME Reno, NV WTOV Steubenville, OH 1 Broadcast Radio (Cox Radio, Inc.) (81) Property Location WSB-AM Atlanta, GA WSB-FM Atlanta, GA WALR-FM Atlanta, GA WBTS-FM Atlanta, GA WFOX-FM Atlanta, GA WBHJ-FM Birmingham, AL WBHK-FM Birmingham, AL WAGG-AM Birmingham, AL WRJS-AM Birmingham, AL WZZK-FM Birmingham, AL WODL-FM Birmingham, AL WBPT-FM Birmingham, AL WEZN-FM Bridgeport, CT WHKO-FM Dayton, OH WHIO-AM Dayton, OH WDPT-FM Dayton, OH WDTP-FM Dayton, OH WJMZ-FM Greenville, NC WHZT-FM Greenville, NC KRTR-FM Honolulu, HI KXME-FM Honolulu, HI 2 KGMZ-FM Honolulu, HI KCCN-FM Honolulu, HI KINE-FM Honolulu, HI KCCN-AM Honolulu, HI KHPT-FM Houston, TX KLDE-FM Houston, TX KTHT-FM Houston, TX KKBQ-FM Houston, TX WAPE-FM Jacksonville, FL WFYV-FM Jacksonville, FL WKQL-FM Jacksonville, FL WMXQ-FM Jacksonville, FL WOKV-AM Jacksonville, FL WBWL-AM Jacksonville, FL WBLI-FM Long Island, NY WBAB-FM Long Island, NY WHFM-FM Long Island, NY WVEZ-FM Louisville, KY WRKA-FM Louisville, KY WSFR-FM Louisville, KY WPTI-FM Louisville, KY WEDR-FM Miami, FL WHQT-FM Miami, FL 3 WFLC-FM Miami, FL WPYM-FM Miami, FL WPLR-FM New -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 96497 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission FCC 96497 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C 20554 INFINITY BROADCASTING ) File Nos. BTC-961230GE, CORPORATION ) BTCH-961230GF, and (Transferor) ) BTCH-961230GG ) and ) ) THE KARMAZEV, CARRUS, WIENER ) VOTING TRUST ) (Transferee) ) ) For Transfer of Control of the Licenses of ) WHOCXAM), Orlando, Florida ) WMMO(FM), Orlando, Florida ) WFTTQ(FM), Orlando, Florida ) ORDER Adopted: December 30,1996 Released: December 30,1996 By the Commission: 1. Before the Commission are the above-captioned applications for the pro forma transfer of control of Infinity Holdings Corp. of Orlando (Infinity Holdings Corp.), licensee of WHOO(AM), WMMO(FM) and WHTQ(FM), Orlando, Florida, from Infinity Broadcasting Corporation (Infinity) to the Karmazin, Carrus, Wiener Voting Trust 2. The Commission has approved the merger of Infinity Broadcasting Corporation ("Infinity") and Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Stockholders of Infinity Broadcasting Corporation. FCC 96-495 (Dec. 26, 19%). Infinity Holdings Corp., the licensee of three stations in Orlando, Florida, WHOO(AM), WHTQ-FM and WMMO-FM, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Infinity. At the time that applications to transfer control of Infinity to Westinghouse were filed, Infinity Holdings Corp. had an agreement to exchange stations with Cox Radio, Inc. Cox and Infinity Holdings Corp. had entered into an agreement for a like-kind exchange of assets so that Infinity would exchange its three Orlando stations for WCKG(FM) and WYSY(FM), two Chicago-area stations controlled by Cox The Commission has also approved the like-kind exchange of these stations between Cox and Infinity Holdings Corp. Infinity. Holdings Corp. of Orlando. FCC 96-494 (Dec. 26, 1996). -

Hoh Retreat September 21St

A monthly publication of the Tampa Chapter, Barbershop Harmony Society Monthly E-Newsletter August 2013 www.HeraldsofHarmony.org In this issue: HoH Calendar of Events ............................2 Quartet News .......................................... 3 Labor Day Jamboree Hangin’ Around The Barber Pole! ..............4 See page 10 HoH Gear & Harmony Marketplace ...........5 Bucs Bucks ...............................................5 History Corner ..........................................6 HoH Retreat District Convention Volunteers .................6 Photo Caption Contest ..............................7 Retreat Info ..............................................7 September 21st Rehearsal Note Summary ......................8-9 See page 7 for more information. Labor Day Jamboree ...............................10 What Did You Do This Summer?.........11-12 Groupanizer News ..................................13 Uploading Songs To Groupanizer .......13-15 CHRISTMAS IS COMING... Pun of the Month ...................................16 Attendance Report .................................16 Reserve December 14th on your calendar SCRIP Gift Cards ......................................16 for the best Christmas show EVER! Chapter Quartets ....................................17 Upcoming Birthdays ..............................17 BACK PAGE 2013 Chapter Leadership Directory HoH Contact Info • Helpful Links Melons, Melons, Newsletter Subscription Info Cantelope, Honeydew... Rehearsals at 7 p.m.: Special Arrangement gets fruity! August 19, 26 Go to page -

Radio Vs. Streaming Services: Exploring How Radio Is Facing Competition

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Radio vs. Streaming Services: Exploring How Radio is Facing Competition Kyra L. Allen University of Central Florida Part of the Radio Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Allen, Kyra L., "Radio vs. Streaming Services: Exploring How Radio is Facing Competition" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 666. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/666 RADIO VS. STREAMING SERVICES: EXPLORING HOW RADIO IS FACING COMPETITION by KYRA ALLEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Program in Radio Television in the College of Sciences and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2020 Thesis Chair: Dr. Bridget Rubenking ABSTRACT With the increasing number of online streaming services available in the world, it is astounding to note how radio is still around maintaining excellent ratings and listener interaction. It is essential to analyze the media industry, and while there are many outlets a person is capable of accessing music, people still turn to their local radio. The literature indicates how the business of radio still exists with the primary competition of today. The study includes interviews from twelve radio professionals at Cox Media Group (CMG) Orlando, the home of seven different format radio stations. -

DOH-Seminole Take a Loved One to the Doctor

th Annual (0 Tom Joyner's For Immediate Release Contact: Monica May 321-281-2019 [email protected] STAR 94.5 & the Florida Department of Health in Seminole County Hosts the th 16 Annual Tom Joyner “Take a Loved One to the Doctor Day” ORLANDO, FL. - Oct.17, 2018 - STAR 94.5 is hosting the 16th Annual Tom Joyner “Take a Loved One to the Doctor Day” (TALO) on Saturday October 27th from 10:00am – 1pm at the Westside Community Center located at 919 Persimmon Avenue in Sanford. This one-day health and wellness fair offers FREE screenings that include: blood pressure, glucose, BMIs, STD, HIV testing and much more. Pregnancy tests, prostate exams, and mental health screenings will also be available to guests. Doctors and nurses will be available to answer questions. There will also be community resources available, free food and prizes. STAR 94.5 joins our STAR Cares partner True Health along with the Florida Department of Health in Seminole County and The City of Sanford to provide our listeners with over $85,000 in FREE health screenings. TALO will also have a variety of fun activities for the entire family. “Seminole County listeners, especially in Sanford, continue to show up in great numbers to this event. That’s why we’re excited to bring it back again,” says Monica May, News/Community Affairs Director and host of the Tom Joyner Morning Show. The event is a partnership with the Florida Department of Health in Seminole County, The City of Sanford District 2 Commissioner Dr. Velma Williams and our STAR Cares partners McCoy Federal Credit Union, Attorney Greg Francis, True Health, Cricket Wireless and Care Plus Health Plans. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored Call Letters Market Station Name Format WAPS-FM AKRON, OH 91.3 THE SUMMIT Triple A WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRQK-FM AKRON, OH ROCK 106.9 Mainstream Rock WONE-FM AKRON, OH 97.5 WONE THE HOME OF ROCK & ROLL Classic Rock WQMX-FM AKRON, OH FM 94.9 WQMX Country WDJQ-FM AKRON, OH Q 92 Top Forty WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary WPYX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY PYX 106 Classic Rock WGNA-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY COUNTRY 107.7 FM WGNA Country WKLI-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 100.9 THE CAT Country WEQX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 102.7 FM EQX Alternative WAJZ-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY JAMZ 96.3 Top Forty WFLY-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY FLY 92.3 Top Forty WKKF-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY KISS 102.3 Top Forty KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary KZRR-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KZRR 94 ROCK Mainstream Rock KUNM-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COMMUNITY RADIO 89.9 College Radio KIOT-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COYOTE 102.5 Classic Rock KBQI-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM BIG I 107.9 Country KRST-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 92.3 NASH FM Country KTEG-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 104.1 THE EDGE Alternative KOAZ-AM ALBUQUERQUE, NM THE OASIS Smooth Jazz KLVO-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 97.7 LA INVASORA Latin KDLW-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM ZETA 106.3 Latin KKSS-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KISS 97.3 FM