Reflections on Eight Summers of Lishma, 1999–2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

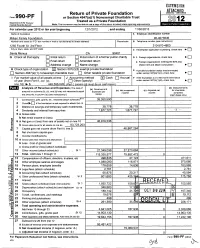

990-PF I Return of Private Foundation

EXTENSION Return of Private Foundation WNS 952 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Reventie Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting req For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/1/2012 , and ending 11/30/2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number Milken Famil y Foundation 95-4073646 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room /suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) 1250 Fourth St 3rd Floor 310-570-4800 City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► Santa Monica CA 90401 G Check all that apply . J Initial return j initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here ► Final return E Amended return 2 . Foreign organizations meeting the 85 % test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization 0 Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust E] Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A). check here ► EJ I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method Q Cash M Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part ll, col (c), Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ---------------------------- ► llne 16) ► $ 448,596,028 Part 1 column d must be on cash basis Revenue The (d ) Disbursements Analysis of and Expenses ( total of (a) Revenue and (b ) Net investment (c) Adjusted net for chartable amounts in columns (b). -

The Impact of Camp Ramah on the Attitudes and Practices Of

122 Impact: Ramah in the Lives of Campers, Staff, and Alumni MITCHELL CoHEN The Impact of Camp Ramah on the Attitudes and Practices of Conservative Jewish College Students Adapted from the foreword to Research Findings on the Impact of Camp Ramah: A Companion Study to the 2004 “Eight Up” Report, a report for the National Ramah Commission, Inc. of The Jewish Theological Seminary, by Ariela Keysar and Barry A. Kosmin, 2004. The network of Ramah camps throughout North America (now serving over 6,500 campers and over 1,800 university-aged staff members) has been described as the “crown jewel” of the Conservative Movement, the most effec- tive setting for inspiring Jewish identity and commitment to Jewish communal life and Israel. Ismar Schorsch, chancellor emeritus of The Jewish Theological Seminary, wrote: “I am firmly convinced that in terms of social import, in terms of lives affected, Ramah is the most important venture ever undertaken by the Seminary” (“An Emerging Vision of Ramah,” in The Ramah Experience, 1989). Research studies written by Sheldon Dorph in 1976 (“A Model for Jewish Education in America”), Seymour Fox and William Novak in 1997 (“Vision at the Heart: Lessons from Camp Ramah on the Power of Ideas in Shaping Educational Institutions”), and Steven M. Cohen in 1998 (“Camp Ramah and Adult Jewish Identity: Long Term Influences”), and others all credit Ramah as having an incredibly powerful, positive impact on the devel- opment of Jewish identity. Recent Research on the Influence of Ramah on Campers and Staff I am pleased to summarize the findings of recent research on the impact of Ramah camping on the Jewish practices and attitudes of Conservative Jewish youth. -

Israel: a Concise History of a Nation Reborn

Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING A book like Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn, by definition covers Israel’s history from a bird’s-eye view. Every event, issue, and personality discussed in these pages has been the subject of much investigation and writing. There are many wonderful books that, by focusing on subjects much more specific, are able to examine the issues the issues covered in this book in much greater detail. The following are my rather idiosyncratic recommendations for a few that will be of interest to the general reader interested in delving more deeply into some of the issues raised in this book. There are many other superb books, not listed here, equally worth reading. I would be pleased to receive your recommendations for works to consider adding. Please feel free to click on the “Contact” button on my website to be in touch. Introduction: A Grand Human Story • Gilbert, Martin. Israel: A History. New York: Harper Perennial, 1998. • Gilbert, Martin. The Story of Israel: From Theodor Herzl to the Roadmap for Peace. London: Andre Deutsch, 2011. • Laqueur, Walter. A History of Zionism: From the French Revolution to the Establishment of the State of Israel. New York: Schocken Books, 1976. • Shapira, Anita. Israel: A History. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2012. • Center for Israel Education online resources: https://israeled.org/ Chapter 1: Poetry and Politics—The Jewish Nation Seeks a Home • Avineri, Shlomo. Herzl: Theodor Herzl and the Foundation of the Jewish State. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2013. -

Ramah Alumni Survey 2016 a Portrait of Jewish Engagement

Ramah Alumni Survey 2016 A Portrait of Jewish Engagement Based on research conducted for the National Ramah Commission by Professor Steven M. Cohen of Hebrew Union College- Jewish Institute of Religion and the Berman Jewish Policy Archive at Stanford University. This study was supported by generous funding from Eileen and Jerry Lieberman. I. INTRODUCTION The comprehensive 2016 Ramah Alumni Survey powerfully demonstrates that Ramah alumni have deep long- term engagement in Jewish life and a network of lifelong Jewish friends. Professor Steven M. Cohen conducted the survey in June and July of 2016, emailing approximately 45,000 invitations to alumni, parents, donors, and other members of the Ramah community. Over 9,500 people responded to the survey. Of the completed surveys, 6,407 were from alumni (Ramah campers, staff members, or both). In his analysis of the survey, Professor Cohen compared the responses of Ramah alumni to those of individuals with similar backgrounds, specifically, respondents to the 2013 Pew study of Jewish Americans who reported that their parents were both Conservative Jews (“the Pew subsample”). Professor Cohen found that even compared to this group of people likely to show greater levels of Jewish engagement than the general Jewish population, Ramah alumni have much higher rates of Jewish involvement across many key dimensions of Jewish life, such as feeling committed to being Jewish, connection to Israel, and participation in synagogue life. In his report, Professor Cohen stated, “We can infer that Camp Ramah has been critical to building a committed and connected core of Conservative and other Jews in North America and Israel.” As a follow-up to Professor Cohen’s analysis, we compared the Ramah alumni responses to those of all Pew respondents who identified as Jews (“Pew overall”). -

The Economic Base of Israel's Colonial Settlements in the West Bank

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Economic Base of Israel’s Colonial Settlements in the West Bank Nu’man Kanafani Ziad Ghaith 2012 The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Promoting knowledge-based policy formulation by conducting economic and social policy research in accordance with the expressed priorities and needs of decision-makers. Evaluating economic and social policies and their impact at different levels for correction and review of existing policies. Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Mohammad Mustafa, Nabeel Kassis, Radwan Shaban, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Samir Abdullah (Director General). Copyright © 2012 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. -

Informal Jewish Education

Informal Jewish Education Camps Ramah Shimon Frost In its last issue, AVAR ve'ATID presented the story of Camps Massad — the first part of the late Shimon Frost's essay comparing Massad and Ramah Hebrew summer camps. The Ramah story, translated from the Hebrew by his widow, Peggy, follows. istorians frequently differ regarding the origins and development of human events. Do persons who initiate and promote actions bring them Habout, or are these people and their ideas also the products of certain changes in society? Ramah's appearance on the American camping scene is a classic example of a combination of both causes. The immediate post-World War II years represented a period of transition and consolidation for American Jewry. Among many Jews, the trauma of the Holocaust caused disillusionment and uncertainty about the future of the Jewish people. In demographic terms, the era is characterized by the transformation of the Jewish community from an immigrant society to one comprised primarily of native-born Jews with deep American roots. This phenomenon, combined with the struggle for a Jewish homeland in Eretz Yisrael, and the efforts to ameliorate conditions of Holocaust survivors in Europe's D.R camps, brought about a greater sense of unity within the Jewish collective. Demobilized Jewish soldiers with their young families began a mass exodus from urban centers to suburbia. In the absence of a "Jewish atmosphere" in these towns, the synagogue became the central Jewish institution in communities which sprang up all over the American continent. The first thing synagogues always did, was to establish an afternoon religious school for their children. -

This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity

This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hoffman, Ari. 2016. This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840682 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity A dissertation presented By Ari R. Hoffman To The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 15, 2016 © 2016 Ari R. Hoffman All rights reserved. ! """! Ari Hoffman Dissertation Advisor: Professor Elisa New Professor Amanda Claybaugh This Year in Jerusalem: Israel and the Literary Quest for Jewish Authenticity This dissertation investigates how Israel is imagined as a literary space and setting in contemporary literature. Israel is a specific place with delineated borders, and is also networked to a whole galaxy of conversations where authenticity plays a crucial role. Israel generates authenticity in uniquely powerful ways because of its location at the nexus of the imagined and the concrete. While much attention has been paid to Israel as a political and ethnographic/ demographic subject, its appearance on the map of literary spaces has been less thoroughly considered. -

Rabbi Chaim Tabasky Bar-Ilan University November 13-18, 2008

Max and Tessie Zelikovitz Centre for Jewish Studies A Week of Jewish Learning Rabbi Chaim Tabasky Bar-Ilan University November 13-18, 2008 Co-sponsored by the Soloway Jewish Community Centre, Congregation Machzikei Hadas, and Congregation Beit Tikvah. Rabbi Chaim Tabasky teaches Talmud at the Machon HaGavoa L’Torah (Institute of Advanced Torah Studies) at Bar Ilan University. He has taught extensively in Jerusalem Yeshivot both for men and women, especially in programs for English speaking academics: (Yeshivat HaMivtar and Michlelet Bruria – Rabbi Chaim Brovender dean; Yeshivat Darchei Noam; Michlala l’Banot in Bayit v’Gan; Nishmat: MaTan) Three Evenings of Torah Two-part series: Shabbaton with Study: An Encounter Rabbi Tabasky, with Talmud Study 1. Anger, Spite and Cruelty in Family Friday, Nov. 14 and Saturday, Nov. 15, Relations; Biblical teachings and 1) Part One: Sunday, Nov 16, 12:30-3:30 Congregation Machzikei Hadas. Modern Applications, Thurs., Nov 13, pm, Soloway Jewish Community Centre 7:00-9:00 pm, Carleton University, Tory 1. Shabbat Dinner: Youth after Trauma: Building Room 446. The workshop will focus on textual study of a New Religious Manifestations among 2. Two Torah-based Analyses of the section of Talmud -- in order to learn about Israeli Youth after Gaza and the Interaction between Divine structure, method, Talmudic logic and a Second Lebanon War, Fri., Nov. 14 Providence and Free Will in Ethical Halachic idea. Even those with little or no 2. Shabbat morning: Drash on the Decisions background will be encouraged to engage Parsha, Sat., Nov. 15 a) The Role of God in the Murder of the Talmudic texts and the sages in a 3. -

Schechter@35: Living Judaism 4

“The critical approach, the honest and straightforward study, the intimate atmosphere... that is Schechter.” Itzik Biton “The defining experience is that of being in a place where pluralism “What did Schechter isn't talked about: it's lived.” give me? The ability Liti Golan to read the most beautiful book in the world... in a different way.” Yosef Peleg “The exposure to all kinds of people and a variety of Jewish sources allowed for personal growth and the desire to engage with ideas and people “As a daughter of immigrants different than me.” from Libya, earning this degree is Sigal Aloni a way to connect to the Jewish values that guided my parents, which I am obliged to pass on to my children and grandchildren.” Schechter@35: Tikva Guetta Living Judaism “I acquired Annual Report 2018-2019 a significant and deep foundation in Halakhah and Midrash thanks to the best teachers in the field.” Raanan Malek “When it came to Jewish subjects, I felt like an alien, lost in a foreign city. At Schechter, I fell into a nurturing hothouse, leaving the barren behind, blossoming anew.” Dana Stavi The Schechter Institutes, Inc. • The Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, the largest M.A. program in is a not for profit 501(c)(3) Jewish Studies in Israel with 400 students and 1756 graduates. organization dedicated to the • The Schechter Rabbinical Seminary is the international rabbinical school advancement of pluralistic of Masorti Judaism, serving Israel, Europe and the Americas. Jewish education. The Schechter Institutes, Inc. provides support • The TALI Education Fund offers a pluralistic Jewish studies program to to four non-profit organizations 65,000 children in over 300 Israeli secular public schools and kindergartens. -

Jewish Summer Camping and Civil Rights: How Summer Camps Launched a Transformation in American Jewish Culture

Jewish Summer Camping and Civil Rights: How Summer Camps Launched a Transformation in American Jewish Culture Riv-Ellen Prell Introduction In the first years of the nineteen fifties, American Jewish families, in unprecedented numbers, experienced the magnetic pull of suburbanization and synagogue membership.1 Synagogues were a force field particularly to attract children, who received not only a religious education to supplement public school, but also a peer culture grounded in youth groups and social activities. The denominations with which both urban and suburban synagogues affiliated sought to intensify that force field in order to attract those children and adolescents to particular visions of an American Judaism. Summer camps, especially Reform and Conservative ones, were a critical component of that field because educators and rabbis viewed them as an experiment in socializing children in an entirely Jewish environment that reflected their values and the denominations‟ approaches to Judaism. Scholars of American Jewish life have produced a small, but growing literature on Jewish summer camping that documents the history of some of these camps, their cultural and aesthetic styles, and the visions of their leaders.2 Less well documented is the socialization that their leaders envisioned. What happened at camp beyond Sabbath observance, crafts, boating, music, and peer culture? The content of the programs and classes that filled the weeks, and for some, the months at camp has not been systematically analyzed. My study of program books and counselor evaluations of two camping movements associated with the very denominations that flowered following 1 World War II has uncovered the summer camps‟ formulations of some of the interesting dilemmas of a post-war American Jewish culture. -

Conservative Judaism 101: a Primer for New Members

CONSERVATIVE JUDAISM 101© A Primer for New Members (And Practically Everyone Else!) By Ed Rudofsky © 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 Table of Contents Page Introduction & Acknowledgements ii About the Author iii Chapter One: The Early Days 1 Chapter Two: Solomon Schechter; the Founding of The United Synagogue of America and the Rabbinical Assembly; Reconstructionism; and the Golden Age of Conservative Judaism 2 Chapter Three: The Organization and Governance of the Conservative Movement 6 Chapter Four: The Revised Standards for Congregational Practice 9 Chapter Five: The ―Gay & Lesbian Teshuvot‖ of 2006 14 Introduction – The Halakhic Process 14 Section I – Recent Historical Context for the 2006 Teshuvot 16 Section II – The 2006 Teshuvot 18 Chapter Six: Intermarriage & The Keruv/Edud Initiative 20 Introduction - The Challenge of Intermarriage 20 Section I – Contemporary Halakhah of Intermarriage 22 Section II – The Keruv/Edud Initiative & Al HaDerekh 24 Section III – The LCCJ Position 26 Epilogue: Emet Ve’Emunah & The Sacred Cluster 31 Sources 34 i Addenda: The Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism A-1 The Sacred Cluster: The Core Values of Conservative Judaism A-48 ii Introduction & Acknowledgements Conservative Judaism 101: A Primer For New Members (And Practically Everyone Else!) originally appeared in 2008 and 2009 as a series of articles in Ha- Hodesh, the monthly Bulletin of South Huntington Jewish Center, of Melville, New York, a United Synagogue-affiliated congregation to which I have proudly belonged for nearly twenty-five (25) years. It grew out of my perception that most new members of the congregation knew little, if anything, of the history and governance of the Conservative Movement, and had virtually no context or framework within which to understand the Movement‘s current positions on such sensitive issues as the role of gay and lesbian Jews and intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews. -

As Some of You Know I Spent the Past Year in Jerusalem. I Walked The

As some of you know I spent the past year in Jerusalem. I walked the cobblestone streets, practiced my Hebrew and a smattering of Arabic, drank coffee in sun soaked cafes, and learned hours and hours of Torah in the beit midrash. But some of my most memorable moments in Israel were spent sitting on the bus. Every day, I would wait for the bus that would take me from the doorstep of Pardes to the Conservative Yeshiva. I would step onboard, and become immersed in snippets of Hebrew, French, Russian, Arabic, and Amaharic surrounding me, a cacophony of words and phrases that I couldn’t even begin to decode. Every now and then I had enough Hebrew to pick out stories from Israeli boys sitting across from me in their white shirts and black pants, complaining about the food in their Yeshiva and alluding to homesickness for parents and siblings. 1 A dirt-spattered four-year-old babbling about his day at Gan, Israeli kindergarten, to his father, who’s only half listening while preoccupied with his phone. And once in a while, an English speaker would walk onto the bus, and I would be dropped into the middle of the saga they were unfolding to their friend; stories of pain, love, tragedy, comedy, hope, and loss. I’d listen for the moment, and then either they would get off the bus, or I would, and their stories would dissipate from my mind, as I raced towards the Conservative Yeshiva, in my mad dash to be on time for my Zo_har class.