Article Analyzing Predictability and Communicating Uncertainty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storms Are Thunderstorms That Produce Tornadoes, Large Hail Or Are Accompanied by High Winds

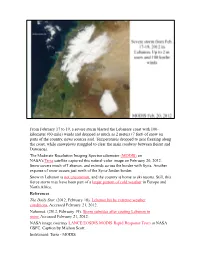

From February 17 to 19, a severe storm blasted the Lebanese coast with 100- kilometer (60-mile) winds and dropped as much as 2 meters (7 feet) of snow on parts of the country, news sources said. Temperatures dropped to near freezing along the coast, while snowplows struggled to clear the main roadway between Beirut and Damascus. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on February 20, 2012. Snow covers much of Lebanon, and extends across the border with Syria. Another expanse of snow occurs just north of the Syria-Jordan border. Snow in Lebanon is not uncommon, and the country is home to ski resorts. Still, this fierce storm may have been part of a larger pattern of cold weather in Europe and North Africa. References The Daily Star. (2012, February 18). Lebanon hit by extreme weather conditions. Accessed February 21, 2012. Naharnet. (2012, February 19). Storm subsides after coating Lebanon in snow. Accessed February 21, 2012. NASA image courtesy LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - MODIS Flooding is the most common of all natural hazards. Each year, more deaths are caused by flooding than any other thunderstorm related hazard. We think this is because people tend to underestimate the force and power of water. Six inches of fast-moving water can knock you off your feet. Water 24 inches deep can carry away most automobiles. Nearly half of all flash flood deaths occur in automobiles as they are swept downstream. -

Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile August 2021

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile August 2021 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Tropical Cyclone Profile Description Tropical cyclones, a general term for tropical storms and hurricanes, are low pressure systems that usually form over the tropics. These storms are referred to as “cyclones” due to their rotation. Tropical cyclones are among the most powerful and destructive meteorological systems on earth. Their destructive phenomena include storm surge, high winds, heavy rain, tornadoes, and rip currents. As tropical storms move inland, they can cause severe flooding, downed trees and power lines, and structural damage. Once a tropical cyclone no longer has tropical characteristics, it is then classified as a post-tropical system. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) has classified four stages of tropical cyclones: • Tropical Depression: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 38 mph (33 knots) or less. • Tropical Storm: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 39 to 73 mph (34 to 63 knots). • Hurricane: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 74 mph (64 knots) or higher. • Major Hurricane: A tropical cyclone with maximum sustained winds of 111 mph (96 knots) or higher, corresponding to a Category 3, 4 or 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Primary Hazards Storm Surge and Storm Tide Storm surge is an abnormal rise of water generated by a storm, over and above the predicted astronomical tide. Storm surge and large waves produced by hurricanes pose the greatest threat to life and property along the coast. They also pose a significant risk for drowning. Storm tide is the total water level rise during a storm due to the combination of storm surge and the astronomical tide. -

Finding Storm Track Activity Metrics That Are Highly Correlated with Weather Impacts

1DECEMBER 2020 Y A U A N D C H A N G 10169 Finding Storm Track Activity Metrics That Are Highly Correlated with Weather Impacts. Part I: Frameworks for Evaluation and Accumulated Track Activity ALBERT MAN-WAI YAU AND EDMUND KAR-MAN CHANG School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, Stony Brook University, State University of New York, Stony Brook, New York (Manuscript received 29 May 2020, in final form 10 August 2020) ABSTRACT: In the midlatitudes, storm tracks give rise to much of the high-impact weather, including precipitation and strong winds. Numerous metrics have been used to quantify storm track activity, but there has not been any systematic evaluation of how well different metrics relate to weather impacts. In this study, two frameworks have been developed to provide such evaluations. The first framework quantifies the maximum one-point correlation between weather impacts at each grid point and the assessed storm track metric. The second makes use of canonical correlation analysis to find the best correlated patterns and uses these patterns to hindcast weather impacts based on storm track metric anomalies using a leave- N-out cross-validation approach. These two approaches have been applied to assess multiple Eulerian variances and Lagrangian tracking statistics for Europe, using monthly precipitation and a near-surface high-wind index as the assessment criteria. The results indicate that near-surface storm track metrics generally relate more closely to weather impacts than upper-tropospheric metrics. For Eulerian metrics, synoptic time scale eddy kinetic energy at 850 hPa relates strongly to both precipitation and wind impacts. -

1.1 the Climatology of Inland Winds from Tropical Cyclones in the Eastern United States

1.1 THE CLIMATOLOGY OF INLAND WINDS FROM TROPICAL CYCLONES IN THE EASTERN UNITED STATES Michael C. Kruk* STG Inc., Asheville, North Carolina Ethan J. Gibney IMSG Inc., Asheville, North Carolina David H. Levinson and Michael Squires NOAA National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, NC landfall than do weaker storms. For these reasons, the 1. Introduction primary impact areas of tropical cyclones are generally found along coastal (or near coastal) regions. Most In the United States, the impacts from tropical previous studies involving the inland-extent of tropical cyclones often extend well-inland after these storms cyclones have generally focused on their expected or make landfall along the coast. For example, after the modeled rate of decay post landfall (e.g., Tuleya et al. passage of Hurricane Camille (1969), more than 150 1984, Kaplan and DeMaria 1995; Kaplan and DeMaria casualties occurred in the state of Virginia, some 1300 2001), while others have focused on recurrence km inland from where the storm originally made landfall thresholds or probabilities of landfalls along a given along the Louisiana coast (Emanuel 2005). According to portion of the United States coastline (e.g., Bove et al. Rappaport (2000), a large portion of fatalities often occur 1998; Elsner and Bossak 2001; Gray and Klotzbach inland associated with a decaying tropical cyclone’s 2005; Saunders and Lea 2005). Results from Kaplan winds (falling trees, collapsed roofs, etc.) and heavy and DeMaria (1995) showed an idealized scenario for flooding rains. In the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, freshwater the maximum possible inland wind speed of a decaying floods accounted for 59 percent of the recorded deaths tropical cyclone based on both intensity at landfall and from tropical cyclones (Rappaport 2000), and such forward motion for the Gulf Coast and southeastern floods are often a combination of meteorological and United States, and for the New England area (Kaplan hydrological factors. -

Hazus Hurricane Model User Guidance

Hazus Hurricane Model User Guidance April 2018 Document History Affected Section or Date Description Subsection First publication using April 2018 Updated user manual from Hazus version 2.1 to Hazus version this format 4.2. Manual has been reorganized from prior version. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Hazus Users and Applications .................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 Hurricane Model Outputs .......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Assumed User Expertise .......................................................................................................... 1-3 1.4 When to Seek Help ................................................................................................................... 1-4 1.5 Technical Support ..................................................................................................................... 1-4 1.6 Uncertainties in Loss Estimates ............................................................................................... 1-5 1.7 Organization of User Guidance ................................................................................................ 1-5 2 OVERVIEW OF THE HURRICANE MODEL ........................................................................................................ -

1 Orographic Effects on Supercell: Development and Structure

Orographic Effects on Supercell: Development and Structure, Intensity and Tracking Galen M. Smith1, Yuh-Lang Lin1,2,@, and Yevgenii Rastigejev1,3 1Department of Energy and Environmental Systems 2Department of Physics 3Department of Mathematics North Carolina A&T State University March 1, 2016 @Corresponding Author Address: Dr. Yuh-Lang Lin, 302H Gibbs Hall, EES, North Carolina A&T State University, 1601 E. Market St., Greensboro, NC 27411. Email: [email protected]. Web: http://mesolab.ncat.edu Abstract Orographic effects on tornadic supercell development, propagation, and structure are investigated using Cloud Model 1 (CM1) with idealized bell-shaped mountains of various heights and a homogeneous fluid flow with a single sounding. It is found that blocking effects are dominative compared to the terrain-induced environmental heterogeneity downwind of the mountain. The orographic effect shifted the track of the storm towards the the left of storm motion, particularly on the lee side of the mountain, when compared to the track in the case with no mountain. The terrain blocking effect also enhanced the supercells inflow, which was increased more than one hour before the storm approached the terrain peak. This allowed the central region of the storm to exhibit clouds with a greater density of hydrometeors than the control. Moreover, the enhanced inflow increased the areal extent of the supercells precipitation, which, in turn enhanced the cold pool outflow serving to enhance the storm’s updraft until becoming strong enough to undercut and weaken the storm considerably. Another aspect of the orographic effects is that down slope winds produced or enhanced low-level vertical vorticity directly under the updraft when the storm approached the mountain peak. -

Manuscript with All Authors Reviewing and Contributing in Various Proportion to Sections

A dynamic and thermodynamic analysis of the 11 December 2017 tornadic supercell in the Highveld of South Africa Lesetja E. Lekoloane1,2, Mary-Jane M. Bopape1, Gift Rambuwani1, Thando Ndarana3, Stephanie Landman1, Puseletso Mofokeng1,4, Morne Gijben1, and Ngwako Mohale1 1South African Weather Service, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa 2Global Change Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2050, South Africa 3Department of Geography, Geoinformatics and Meteorology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa 4School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2050, South Africa Correspondence: Lesetja Lekoloane ([email protected]) Abstract. On 11 December 2017, a tornadic supercell initiated and moved through the northern Highveld region of South Africa for 7 hours. A tornado from this supercell led to extensive damage to infrastructure and caused injury to and displacement of over 1000 people in Vaal Marina, a town located in the extreme south of the Gauteng Province. In this study we conducted an analysis in order to understand the conditions that led to the severity of this supercell, including the formation 5 of a tornado. The dynamics and thermodynamics of two configurations of the Unified Model (UM) were also analysed to assess their performance in predicting this tornadic supercell. It was found that this supercell initiated as part of a cluster of multicellular thunderstorms over a dryline, with three ingredients being important in strengthening and maintaining it for 7 hours: significant surface to mid-level vertical shear, an abundance of low-level warm moisture influx from the tropics and Mozambique Channel, and the relatively dry mid-levels (which enhanced convective instability). -

10.2 TORNADIC MINI-SUPERCELLS in NORTHERN CANADA Patrick J

10.2 TORNADIC MINI-SUPERCELLS IN NORTHERN CANADA Patrick J. McCarthy*, Sandra Massey Prairie and Arctic Storm Prediction Centre Meteorological Service of Canada Dave Patrick Hydrometeorological and Arctic Laboratory Meteorological Service of Canada 1. INTRODUCTION Supercell tornadoes are not uncommon on representative of the atmospheric profile the Canadian Prairies. On average, over Grande Prairie. Therefore, the approximately 42 tornadoes (McDonald, following upper air assessments are all 2005) are reported annually in this region, subjective interpolations derived from the with supercells accounting for roughly 75% upper air charts and serve only as a rough of those events. The remaining are non- approximation. supercell tornadoes, forming from weaker and, apparently, less organized convection. The surface winds at Grande Prairie were northwest at 12 knots until the time of the On July 8, 2004, a large weather system tornado when they veered to northeasterly 5 over the western Canadian Prairies to 10 knots. At 00Z July 9, 2006, winds at produced a wide variety of storm types 850 hpa were north to northwesterly at 10 including one unique tornadic event. In a knots, northeasterly 15-25 knots at 700 hpa, cool and moist part of this environment, a northeasterly 20-30 knots at 500 hpa, and line of very small thunderstorms developed northeasterly 30-40 knots at 250 hpa. and tracked from generally east to west. Persistent rotation was observed in virtually From 18Z to 21Z, there appeared to be a every significant cell within in this line. One surface convergence line to the northeast of of these small storms produced an F1 Grande Prairie with northwesterly winds on tornado that tracked through part of the city the southwest side and northeasterly winds of Grande Prairie, Alberta (latitude 55.1˚N). -

Chang Et Al. (2002)

15 AUGUST 2002 CHANG ET AL. 2163 Storm Track Dynamics EDMUND K. M. CHANG* Department of Meteorology, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida SUKYOUNG LEE Department of Meteorology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania KYLE L. SWANSON Atmospheric Sciences Group, University of WisconsinÐMilwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Manuscript received 17 July 2001, in ®nal form 3 January 2002) ABSTRACT This paper reviews the current state of observational, theoretical, and modeling knowledge of the midlatitude storm tracks of the Northern Hemisphere cool season. Observed storm track structures and variations form the ®rst part of the review. The climatological storm track structure is described, and the seasonal, interannual, and interdecadal storm track variations are discussed. In particular, the observation that the Paci®c storm track exhibits a marked minimum during midwinter when the background baroclinicity is strongest, and a new ®nding that storm tracks exhibit notable variations in their intensity on decadal timescales, are highlighted as challenges that any comprehensive storm track theory or model has to be able to address. Physical processes important to storm track dynamics make up the second part of the review. The roles played by baroclinic processes, linear instability, downstream development, barotropic modulation, and diabatic heating are discussed. Understanding of these processes forms the core of our current theoretical knowledge of storm track dynamics, and provides a context within which both observational and modeling results can be interpreted. The eddy energy budget is presented to show that all of these processes are important in the maintenance of the storm tracks. The ®nal part of the review deals with the ability to model storm tracks. -

Upper Great Lakes Storm Track Climatology 2006-2012

John Boris National Weather Service Gaylord MI 2012 Winter Talk Series What are we referring to when we talk about “storm tracks”? A storm track is the path that an area of low pressure takes during its lifetime...from initial development to dissipation. It has long been recognized that there are preferred areas of low pressure development...or what meteorologists refer to as “cyclogenesis”. Where a storm system initially develops can have a large influence on its future impacts on downstream locations. So why is knowing the track of a storm important? One of the biggest reasons storm track is important is due to the temperature structure around a major storm system. Whether you are on the “warm” or “cold” side of a storm has a major impact on what type (or types) of precipitation you may receive. Another important aspect of storm track is precipitation amount...especially when dealing with snowfall. This is why forecasters spend a lot of time trying to determine an accurate storm track for winter storms...given the many implications based on exactly where a low pressure system will go. Conceptual Model of a Typical Winter Storm Conceptualized precip type distribution in a mature winter storm. SN SN SN “Cold Side” ZR/IP/SN/RA SN L RA RA “Warm Side” RA 0c RA 850mb What is a storm track climatology? A storm track climatology is tracing the history of storm systems over a given number of years. This can give insight into where storms typically form. In the case of this study...we wanted to look at where storms that impact the Upper Great Lakes region typically develop. -

Long Term Analysis of Convective Storm Tracks Based on C-Band Radar Reflectivity Measurements

ERAD 2010 - THE SIXTH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE ON RADAR IN METEOROLOGY AND HYDROLOGY Long term analysis of convective storm tracks based on C-band radar reflectivity measurements Edouard Goudenhoofdt, Maarten Reyniers and Laurent Delobbe Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium, 1180 Brussels , Belgium, www.meteo.be 1. Introduction The very short forecasting or nowcasting of convective storms is a highly challenging problem due to the wide variety of spatial scales and processes involved. The state of the art numerical weather prediction models generally fail in predicting convective storms initiation and development with reasonable accuracy. Weather radars are intensively used by forecasters during convective situation. A radar provides instantaneous reflectivity measurements of precipitation at a spatial scale of about 1km. Convective storms, which occur at a spatial scale of a few kilometers, can then be detected by the radar. Moreover, if the time resolution is short enough, the convective storm evolution can be monitored across successive radar images. Based on those snapshots, the motion of a convective cell can be estimated and used to forecast its future position. However, this simple method does not take into account storm growth, decay and direction changes. For this purpose, a better knowledge of storm evolution characteristic is required. The Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium has several years of archived volume data from a C-band radar. To process those data, the cell tracker TITAN (NCAR) has recently been installed at RMI. The behavior of this tracking system has been investigated through a sensitivity study to some parameters. The storm tracks provided by TITAN have been analysed by a suitable statistic tool. -

DRYLINE MAGIC by Tim Marshall (Published in Weatherwise Magazine in 1992)

DRYLINE MAGIC by Tim Marshall (published in Weatherwise Magazine in 1992) Every spring, veteran storm chasers head to West Texas to catch a weather show they call "dryline magic". The dryline is a boundary that separates hot, dry air to the west from warm, moist air to the east. During the spring, it lurks on the western high plains. The dryline moves east during the day, acting like a rotary plow, churning up the warm, moist air ahead of it. If there is enough moisture and instability in the warm air, severe storms can form, storms that often produce high winds, large hail, and tornadoes. A dryline storm is more isolated, more visible, and more violent than any other type of storm. Storm chasers love them. Once they've seen one, most forget all about the fast-moving squall lines associated with cold fronts and the low-visibility storms along warm fronts. I've driven through many drylines. One morning, while driving east of Lubbock, Texas, in hot, dry air, it seemed as if I suddenly hit a waterfall! The parched air in the car immediately became saturated and the windows all fogged up. Looking north and south along the dryline, I could see the cross sections of the two distinct air masses. To the west, the sky was sharp and clear, and distant cumulus clouds were crisp and white. In contrast, to the east, the air mass was hazy and cloudy, and I could make out only a few rows of yellow fuzzy cumulus before visibility faded into obscurity.