Apparent Natural Recolonization of an Island by the Seychelles Kestrel (Falco Araea)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inner Islands of the Seychelles (Sea Shell & Sea

THE INNER ISLANDS OF THE SEYCHELLES (SEA SHELL & SEA PEARL) Isolated in the Indian Ocean and the only mid-ocean islands of /> granite formation to be found on earth, the Seychelles archipelago is often mentioned in the same breath as the lost Situated some 1,500 kilometers east of mainland Africa, and 'Garden of Eden.' northeast of the island of Madagascar, this tiny island group boasts a population of just 90,000 inhabitants, with a warm, tropical climate all year-round and some of the most stunningly beautiful beaches in the world. The highest peaks of a submerged mountain range that broke apart from the supercontinent of Gondwana millions of years ago, the Seychelles' inner islands are the most ancient islands on earth - no other mid-ocean isles of granite formation can be Mahe, the largest island, is home to the majority of the found anywhere else. This curious geological feature was one of population and represents the archipelago's commercial and several curiosities about the islands that led the famed British transportation hub, with the country's only international airport General, Charles Gordon, to declare Seychelles the site of the linking the islands to the rest of the globe. The island is biblical Garden of Eden. characterised by its towering granite peaks, lush mist forests and dozens of striking coves and beaches. The second largest island, Praslin, is home to the legendary Vallee de Mai, the UNESCO World Heritage Site where the Coco de Mer grows in abundance. This double coconut, which curiously resembles the shape of a woman's pelvis, was another facet of General Gordon's theory about Seychelles as the Garden of Eden - he believed it to be the real forbidden fruit. -

Vallee De Mai Nature Reserve Seychelles

VALLEE DE MAI NATURE RESERVE SEYCHELLES The scenically superlative palm forest of the Vallée de Mai is a living museum of a flora that developed before the evolution of more advanced plant families. It also supports one of the three main areas of coco-de-mer forest still remaining, a tree which has the largest of all plant seeds. The valley is also the only place where all six palm species endemic to the Seychelles are found together. The valley’s flora and fauna is rich with many endemic and several threatened species. COUNTRY Seychelles NAME Vallée de Mai Nature Reserve NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1983: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following Statement of Outstanding Universal Value at the time of inscription Brief Synthesis Located on the granitic island of Praslin, the Vallée de Mai is a 19.5 ha area of palm forest which remains largely unchanged since prehistoric times. Dominating the landscape is the world's largest population of endemic coco-de- mer, a flagship species of global significance as the bearer of the largest seed in the plant kingdom. The forest is also home to five other endemic palms and many endemic fauna species. The property is a scenically attractive area with a distinctive natural beauty. Criterion (vii): The property contains a scenic mature palm forest. The natural formations of the palm forests are of aesthetic appeal with dappled sunlight and a spectrum of green, red and brown palm fronds. -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa. -

Annex a Species Are the Most Endangered, and Most Protected Species and Trade Is Very Strictly Controlled

Raptor Rescue Rehabilitation Handbook APPENDIX B What do the various CITES Annex listings mean? The annex is the critical listing which defines what you can or cannot do with a specimen. Annex A species are the most endangered, and most protected species and trade is very strictly controlled. Unless the specimen is covered by a certificate from the UK CITES Management Authority you cannot legally use it for any commercial purpose, whether or not direct payment is involved. This includes offer to buy, buy, keep for sale, offer for sale, transport for sale, sell, advertise for sale, exchange for anything else, or display to paying customers. To import or (re)export such a specimen into or out of the EU requires both an import permit and an (re)export permit. You will therefore need to contact the management authorities in the countries of export and import, prior to such a move. Annex B species can be traded within the EU providing you can prove “legal acquisition” i.e. the specimen has not been taken from the wild illegally or smuggled into the EU. Annex B specimens which are imported into or (re)exported from the EU require the same documentation as for Annex A specimens (see above) Annex C and D species require an ‘Import Notification’ form to be completed at the time you make your import. To obtain a copy of the form ring 0117 372 8774 The following species are listed on Annex A. Falconiformes Andean Condor Vultur gryphus California Condor Gymnogyps califorianus Osprey Pandion haliaetus Cinereous Vulture Aegypius monachus Egyptian Vulture -

Praslin, Seychelles

EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW TO ENJOY YOUR NEXT DREAM DESTINATION! INDIAN OCEAN| PRASLIN, SEYCHELLES PRASLIN BASE ADDRESS Praslin Baie Sainte Anne Praslin 361 GPS POSITION: 4°20.800S 55°45.909E OPENING HOURS: 8:30am – 5pm BASE MAP BASE CONTACTS If you need support while on your charter, contact the base immediately using the contact details in this guide. Please contact your booking agent for all requests prior to your charter. BASE MANAGER Base Manager: Pierre Piveteau Phone: +248 25 27 662 Email: [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE PRASLIN Customer Service Manager: Devina Bouchereau Phone: +248 26 44 701 Email: [email protected] BASE FACILITIES ☒ Electricity ☒ Luggage storage ☒ Water ☐ Restaurant ☒ Toilets ☐ Bar ☒ Showers ☒ Supermarket / Grocery store ☒ Laundry ☐ ATM ☐ Swimming pool ☐ Post Office ☐ Wi-Fi BASE INFORMATION LICENSE Sailing license required: ☒ Yes ☐ No PAYMENT The base can accept: ☒ Visa ☒ MasterCard ☐ Amex ☒ Cash EMBARKATION TIME Embarkation is 3pm. YACHT BRIEFING All briefings are conducted on the chartered yacht and will take 40-60 minutes, depending on yacht size and crew experience. The team will give a detailed walk-through of your yacht’s technical equipment, information about safe and accurate navigation, including the yacht’s navigational instruments, as well as mooring, anchorage and itinerary help. The safety briefing introduces the safety equipment and your yacht’s general inventory. STOP OVERS For all DYC charters starting and/or ending in Praslin, the first and last night at the marina is free of charge, including water, electricity and use of shower facilities. DISEMBARKATION TIME Disembarkation is at 9am. The team will inspect your yacht’s equipment and a general visual check of its interior and exterior. -

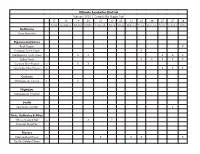

Ultimate Seychelles Bird List February 2020 | Compiled by Pepper Trail

Ultimate Seychelles Bird List February 2020 | Compiled by Pepper Trail 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 At Sea Assumption Aldabra Aldabra Cosmoledo Astove At Sea Alphonse Poivre Desroches Praslin La Digue Mahe Galliforms Gray Francolin Pigeons and Doves Rock Pigeon X European Turtle-Dove X Madagascar Turtle-Dove x X X X X X Zebra Dove X X X X X Comoro Blue-Pigeon x X X Seychelles Blue-Pigeon x X X X Cuckoos Madagascar Coucal x X Nightjars Madagascar Nightjar Swifts Seychelles Swiftlet x X Rails, Gallinules & Allies White-throated Rail x X ? Eurasian Moorhen Plovers Black-bellied Plover x X X X X Pacific Golden-Plover Ultimate Seychelles Bird List February 2020 | Compiled by Pepper Trail 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 At Sea Assumption Aldabra Aldabra Cosmoledo Astove At Sea Alphonse Poivre Desroches Praslin La Digue Mahe Lesser Sand-Plover x X Greater Sand-Plover x X X Common Ringed Plover Sandpipers Whimbrel x X X X X X X Eurasian Curlew Bar-tailed Godwit Ruddy Turnstone x X X X X X Curlew Sandpiper x X X Sanderling x X X Little Stint Terek Sandpiper Common Sandpiper x X Common Greenshank x X X X Wood Sandpiper Crab-Plover x X X X X X Gulls and Terns Brown Noddy x X X X X X X X X Lesser Noddy x X White Tern x X X X X X X X X Sooty Tern Bridled Tern x X X X Saunders’s Tern White-winged Tern Roseate Tern Ultimate Seychelles Bird List February 2020 | Compiled by Pepper Trail 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 At Sea Assumption Aldabra Aldabra Cosmoledo Astove At Sea Alphonse Poivre Desroches Praslin La Digue Mahe Black-naped -

Assessment of the Genetic Potential of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco Peregrinus Peregrinus) Population Used in the Reintroduction Program in Poland

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Assessment of the Genetic Potential of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus peregrinus) Population Used in the Reintroduction Program in Poland Karol O. Puchała 1,* , Zuzanna Nowak-Zyczy˙ ´nska 1, Sławomir Sielicki 2 and Wanda Olech 1 1 Department of Animal Genetics and Conservation, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, 02-787 Warszawa, Poland; [email protected] (Z.N.-Z.);˙ [email protected] (W.O.) 2 Society for Wild Animals “Falcon”, 87-800 Włocławek, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Microsatellite DNA analysis is a powerful tool for assessing population genetics. The main aim of this study was to assess the genetic potential of the peregrine falcon population covered by the restitution program. We characterized individuals from breeders that set their birds for release into the wild and birds that have been reintroduced in previous years. This was done using a well-known microsatellite panel designed for the peregrine falcon containing 10 markers. We calculated the genetic distance between individuals and populations using the UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) method and then performed a Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) and constructed phylogenetic trees, to visualize the results. In addition, we used the Bayesian clustering method, assuming 1–15 hypothetical populations, to find the model that best fit the data. Citation: Puchała, K.O.; Units were segregated into groups regardless of the country of origin, and the number of alleles ˙ Nowak-Zyczy´nska,Z.; Sielicki, S.; and observed heterozygosity were different in different breeding groups. -

Hawksbill Turtle Monitoring in Cousin Island Special Reserve, Seychelles: an Eight-Fold Increase in Annual Nesting Numbers

Vol. 11: 195–200, 2010 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online April 30 doi: 10.3354/esr00281 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Hawksbill turtle monitoring in Cousin Island Special Reserve, Seychelles: an eight-fold increase in annual nesting numbers Zoë C. Allen1,*, Nirmal J. Shah1, Alastair Grant2, Gilles-David Derand1, Diana Bell2 1Nature Seychelles, PO Box 1310, The Centre for Environment & Education, Roche Caiman, Mahe, Seychelles 2School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Norfolk NR4 7TJ, UK ABSTRACT: Results of hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata nest monitoring on Cousin Island, Seychelles, indicate an 8-fold increase in abundance of nesting females since the early 1970s when the population was highly depleted. From 1999 to 2009, the population increased at an average rate of 16.5 turtles per season. Females were individually tagged, and nesting data were derived from indirect evidence of nesting attempts (i.e. tracks) and actual turtle sightings (56 to 60% of all encoun- ters). Survey effort varied over the years for a variety of reasons, but the underlying trends over time are considered robust. To overcome biases associated with variable survey effort, we estimated pop- ulation changes by fitting a Poisson distribution to data on numbers of times each individual was seen at this breeding site in a season. This was used to estimate unseen individuals, and hence the total number of nesting females each season. The maximum number of individuals emerging onto Cousin Island to nest within a single season was estimated to be 256 (2007 to 2008) compared to 23 in 1973. Tag returns indicate that many turtles nest on both Cousin and Cousine Islands (2 km apart), and that some inter-island nesting also occurs between Cousin and more remote islands within the Seychelles. -

Seychelles Coastal Management Plan 2019–2024 Mahé Island, Seychelles

Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change Seychelles Coastal Management Plan 2019–2024 Mahé Island, Seychelles. Photo: 35007 Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change Seychelles Coastal Management Plan 2019–2024 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with the Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change of Seychelles. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors or the governments they represent, and the European Union. In addition, the European Union is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denomina- tions, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Phelsuma 19.Indd

Development on Silhouette Harbour construction Since the 19th century access to most of Silhouette was via the narrow pass through the reef at La Passe and the settlement’s jetty (Fig. 16a). In 2000 the pass was widened and deepened, and a harbour excavated (Fig. 16b). The impacts on the natural environment were considerable in the short term, resulting in the death of thousands of reef-flat animals (most obviously molluscs, brittle stars and sea cucumbers – Fig. 17). In 2005 the channel was cleared from coral regrowth by blasting, this caused some fish mortality at the time (Fig. 17). Fig. 16 La Passe sea access. a) La Passe in 1960 b) in 2006 c) view of harbour in 2006 96 The harbour improved access to the island, enabling larger vessels to reach the shore. This also increased vulnerability of the island to new human impacts. In September 2005 an oil spill occurred in the harbour when a boat carrying waste oil from North Island to Mahé developed a leak and made an emergency stop in the Silhouette harbour (Gerlach 2005). The vessel was beached on Silhouette on 7th September and patched. It was refloated on 10th September but the repairs were not successful. It sank in the harbour in the night of 11th September. Oil was observed leaking from the wreck (Fig. 18), although this was reported to IDC and the vessel’s owners no action was taken. The Ministry of Environment sent a clean-up team but this did not arrive until after the floating oil had been flushed out of the harbour by a falling tide. -

Splendours of the Seychelles

SPECIAL OFFER -SAVE £500 PER PERSON SplenDOUrs of THE SEYCHELLES AN islanD HoppinG EXpeDITion CRUISE THroUGH THE SEYCHELLES ABoarD THE MS CALEDONIAN SKY 18TH TO 29TH NOVEMBER 2020 Curieuse Island e find it difficult to imagine a more perfect way to escape the British winter than to SEYCHELLES INDIAN OCEAN Praslin, Grande Soeur, enjoy the warmth and beauty of the Indian Ocean aboard the MS Caledonian Sky as Aride & Curieuse sheW undertakes exactly the type of itinerary which suits her many talents best. In the depth Amirante Islands Mahe of winter at home, you can join our all-suite vessel for an exploration of the islands and Aldabra Island atolls of the Seychelles, one of the world’s most pristine and picturesque archipelagos and a Group Alphonse Islands veritable feast of beauty, the natural world and island culture. Farquhar Islands Our expedition focuses on the remote Outer Seychelles, tiny untouched islands and atolls of the Amirante Islands, Farquhar, Aldabra and Alphonse Groups. These minute dots on an atlas are truly magical places. For many the greatest highlight will be our visit to Aldabra, the world’s largest coral atoll and the last breeding ground of the giant tortoise and in addition to seeing some of these endearing creatures you should also encounter dolphins, turtles and whales as well as countless birds including the flightless rail, the last flightless bird in the Indian Ocean. Totally untouched by the modern world, Aldabra was described by Jacques Cousteau as ‘the last unprofaned sanctuary on this planet’. It is one of the most difficult places on earth to access and a lack of fresh water has saved Aldabra from any tourism development. -

American Kestrel

Department of Planning and Natural Resources Division of Fish and Wildlife U.S.V.I. Animal Fact Sheet #05 American Kestrel Falco sparverius Taxonomy Kingdom - - - - - Animalia Phylum - - - Chordata Subphylum - - - Vertebrata Class - - - - Aves Subclass - - - Neornithes Order - - - Falconiformes Family - - Falconidae Genus - - Falco Species - sparverius Subspecies (Caribbean) - caribbaearum Identification Characteristics ♦ Length - 19 to 21 cm ♦ Wingspan - 50 to 60 cm ♦ Weight (males) - 102 to 120 gm ♦ Weight (females) - 126 to 166 gm ♦ Facial bars - two ♦ Color of tail & back - rusty reddish ♦ Tail pattern - black band at tip Description wings are rusty brown like their back and their tail The American kestrel, Falco sparverius, is a is rusty reddish with a black band at the end. common falcon in the Virgin Islands. Although frequently called a "sparrow” hawk - in reference Distribution & Habitat to its small size - these kestrels eat more than The American Kestrel permanently inhabits sparrows. Locally, the American Kestrel is also (without seasonal migration) North and South known as the killy-killy, probably because of the America from near the tree line in Alaska and shrieking sounds they make. Canada, south to Tierra del Fuego. The bird can The American Kestrel is the smallest raptor in also be found in the West Indies, the Juan our area. Worldwide, the only smaller species in Fernandez Islands and Chile. It is largely absent the genus Falco is the Seychelles kestrel. from heavily forested areas, including Amazonia. Generally, the American Kestrel is about 20 cm The American Kestrel nests in tree cavities, long, with a wingspan of 50 to 60 cm. Males woodpecker holes, crevices of buildings, holes in weigh from 103 to 120 g and females between 126 banks, nest boxes or, rarely, old nests of other and 166 g.