When Art Fails Humanity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

L'œuvre Et Ses Contextes

L’œuvre et ses contextes I. Radiguet, le jeune homme à la canne A. Quelques repères biographiques 1903 Raymond Radiguet naît le 18 juin à Saint-Maur. Il quitte l’école communale. Il entre au lycée Charlemagne. 1913 Commence une longue période de lecture et d’écriture de poèmes. 1914 Il est témoin du début de la première guerre mondiale. En avril, dans le train il rencontre Alice, âgée de 24 ans, 1917 mariée à un soldat parti au front. Il devient son amant. Il montre ses premiers vers à André Salmon, poète. Il rencontre Max Jacob et commence à fréquenter les milieux littéraires parisiens. Il publie des poèmes et des contes dans le Canard enchaîné 1918 sous un pseudonyme : Rajky. Il écrit dans une revue avant-gardiste : Sic. Il collabore aux revues Dada de Tristan Tzara et Littérature de André Breton. 1919 Il devient un ami très proche de Jean Cocteau. Le Diable au corps 6 Il assiste au lancement du Bœuf sur le toit, ballet-pantomime de Cocteau et Milhaud Il participe à la création de la revue Le coq. Il écrit avec Cocteau le livret d’un opéra comique intitulé Paul et Virginie, 1920 sur une musique de Satie Il écrit une comédie : Les Pélicans. Il publie sa véritable première œuvre littéraire, un recueil de poésie : les Joues en feu. Il part dans le Var et écrit une nouvelle : Denise. 1921 De retour à Paris, il assiste à la représentation de certaines de ses œuvres. Il commence la rédaction de son premier roman : Le Diable au corps. -

JEAN COCTEAU (1889-1963) Compiled by Curator Tony Clark, Chevalier Dans L’Ordre Des Arts Et Des Lettres

JEAN COCTEAU (1889-1963) Compiled by curator Tony Clark, Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres 1889 Jean Maurice Clement Cocteau is born to a wealthy family July 5, in Maisons Laffite, on the outskirts of Paris and the Eiffel Tower is completed. 1899 His father commits suicide 1900 - 1902 Enters private school. Creates his first watercolor and signs it “Japh” 1904 Expelled from school and runs away to live in the Red Light district of Marsailles. 1905 - 1908 Returns to Paris and lives with his uncle where he writes and draws constantly. 1907 Proclaims his love for Madeleine Carlier who was 30 years old and turned out to be a famous lesbian. 1908 Published with text and portraits of Sarah Bernhardt in LE TEMOIN. Edouard de Max arranges for the publishing of Cocteau’s first book of poetry ALLADIN’S LAMP. 1909 - 1910 Diaghailev commissions the young Cocteau to create two lithographic posters for the first season of LES BALLETS RUSSES. Cocteau creates illustrations and text published in SCHEHERAZADE and he becomes close friends with Vaslav Nijinsky, Leon Bakst and Igor Stravinsky. 1911 - 1912 Cocteau is commissioned to do the lithographs announcing the second season of LES BALLETS RUSSES. At this point Diaghailev challenges Cocteau with the statement “Etonnez-Moi” - Sock Me. Cocteau created his first ballet libretti for Nijinsky called DAVID. The ballet turned in the production LE DIEU BLU. 1913 - 1915 Writes LE POTOMAK the first “Surrealist” novel. Continues his war journal series call LE MOT or THE WORD. It was to warn the French not to let the Germans take away their liberty or spirit. -

Bibliographie De La Correspondance De Max Jacob Antonio Rodriguez, Patricia Sustrac

Bibliographie de la correspondance de Max Jacob Antonio Rodriguez, Patricia Sustrac To cite this version: Antonio Rodriguez, Patricia Sustrac. Bibliographie de la correspondance de Max Jacob. Les Cahiers Max Jacob, Association des Amis de Max Jacob (AMJ), 2014, pp.311-325. hal-01806622 HAL Id: hal-01806622 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01806622 Submitted on 9 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. BIBLIOGRAPHIE DE LA CORRESPONDANCE DE MAX JACOB Antonio RODRIGUEZ et Patricia SUSTRAC ous mentionnons dans cette section les correspondances parues unique- Nment en recueils, incluant celles parues dans Les Cahiers Max Jacob. Les correspondances sont classées par leur titre après l’astérisque si elles sont éditées de manière chronologique ou par ordre alphabétique selon leur destinataire. Lorsque le lieu d’édition est Paris, celui-ci n’a pas été indiqué. Pour les publi- cations parues en revues, se reporter à l’instrument bibliographique : GREEN Maria, Bibliographie et documentation sur Max Jacob, Saint-Étienne : Les Amis de Max Jacob, 1988. Nous indiquons également les correspondances à paraître, les fonds archivistiques contenant des correspondances de Max Jacob appar- tenant à des collections publiques ou privées, ainsi que les principales études consacrées à l’épistolaire de l’auteur. -

N°27 - 2009 Mep Clio 94 20092.Qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 2

mep clio 94 20092.qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 1 N°27 - 2009 mep clio 94 20092.qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 2 Volume publié avec le concours de la Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles d’Ile-de-France et du Conseil Général du Val-de-Marne. Clio 94 mep clio 94 20092.qxd 16/09/09 11:52 Page 3 SOMMAIRE PRÉFACE ................................................................................................. P.5 (MICHEL BALARD) LES COURS DE MANDRES .......................................................................... P.7 (JEAN-PIERRE NICOL) MANDRES VUE PAR SES ÉCRIVAINS .......................................................... P.23 (JEAN-PIERRE NICOL) ALFORTVILLE EN TOILE DE FOND (1870-1944) ......................................... P.31 (LOUIS COMBY) MAIRIE, ÉCOLE ET PAUVRETÉ, L’EXEMPLE DU SUD-EST PARISIEN, 1880-1900 .......................................... P.44 (CÉCILE DUVIGNAC-CROISÉ) PAUVRETÉ ET MARGINALITÉ DANS LE SUD-EST PARISIEN (ACTES DU COLLOQUE DE CLIO 94 DU 2 NOVEMBRE 2008) INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... P.59 (GENEVIEVE ARTIGAS-MENANT) TOURISME ET VILLÉGIATURE À ARCUEIL ET EN VALLÉE INFÉRIEURE DE LA BIÈVRE EN AMONT DE PARIS DU XVIE SIECLE AU DÉBUT DU XXIE SIECLE ...............................................P.65 (ROBERT TOUCHET) MAISONS-ALFORT, À TRAVERS L’ÉCRITURE, LA PEINTURE ET LA PHOTOGRAPHIE ......................................................... P.69 (MARCELLE AUBERT) LA ZONE, DE L’UNIVERS LITTÉRAIRE À LA RÉALITÉ HISTORIQUE ............... P.83 (ÉLISE -

The Jean Cocteau Collection: How 'Astonishing'?

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Spring 1988 The Jean Cocteau Collection: How 'Astonishing'? Paul J. Archambault Syracuse University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Archambault, Paul J. "The Jean Cocteau Collection: How 'Astonishing'?" The Courier 23.1 (1988): 33-48. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 1, SPRING 1988 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXIII NUMBER ONE SPRING 1988 The Forgotten Brother: Francis William Newman, Victorian Modernist By Kathleen Manwaring, Syracuse University Library 3 The Joseph Conrad Collection at Syracuse University By J. H. Stape, Visiting Associate Professor of English, 27 Universite de Limoges The Jean Cocteau Collection: How 'Astonishing'? By Paul J. Archambault, Professor of French, 33 Syracuse University A Book from the Library of Christoph Scheurl (1481-1542) By Gail P. Hueting, Librarian, University of Illinois at 49 Urbana~Champaign James Fenimore Cooper: Young Man to Author By Constantine Evans, Instructor in English, 57 Syracuse University News of the Syracuse University Library and the Library Associates 79 The Jean Cocteau Collection: How 'Astonishing'? BY PAUL J. ARCHAMBAULT Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) is reputed to have been the most 'as, tonishing' of French twentieth,century artists. In one of his many autobiographical works, La Difficulte d'etre, he tells how, one day in 1909, he was walking on the Place de la Concorde with Sergei Dia, ghilev, who had captivated Paris the previous year with his Ballets Russes, and Vaslav Nijinsky, his greatest dancer. -

Rewriting the Twentieth-Century French Literary Right: Translation, Ideology, and Literary History

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses March 2017 Rewriting the Twentieth-century French Literary Right: Translation, Ideology, and Literary History Marcus Khoury University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Khoury, Marcus, "Rewriting the Twentieth-century French Literary Right: Translation, Ideology, and Literary History" (2017). Masters Theses. 469. https://doi.org/10.7275/9468894 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/469 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REWRITING THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FRENCH LITERARY RIGHT: TRANSLATION, IDEOLOGY, AND LITERARY HISTORY A Thesis Presented by MARCUS KHOURY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2017 Comparative Literature Translation Studies Track Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures © Copyright by Marcus Khoury 2017 All Rights Reserved REWRITING THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY FRENCH LITERARY RIGHT: TRANSLATION, IDEOLOGY, AND LITERARY HISTORY A Thesis -

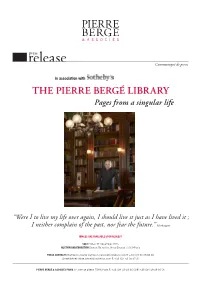

THE PIERRE BERGÉ LIBRARY Pages from a Singular Life

in association with THE PIERRE BERGÉ LIBRARY Pages from a singular life “Were I to live my life over again, I should live it just as I have lived it ; I neither complain of the past, nor fear the future.” Montaigne IMAGES ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST SALE Friday 11 December 2015 AUCTION AND EXHIBITION Drouot Richelieu, 9 rue Drouot 75009 Paris PRESS CONTACTS Sophie Dufresne [email protected] T. +33 (0)1 53 05 53 66 Chloé Brézet [email protected] T. +33 (0)1 53 05 52 32 PIERRE BERGÉ & ASSOCIÉS PARIS 92 avenue d’Iéna 75116 Paris T. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 00 F. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 01 Beginning in DECember 2015, Pierre BergÉ & ASSOCIÉS, in CollAborAtion With SothebY’S, Will be AUCtioning the PERSonAL librARY of Pierre BergÉ. This collection includes 1,600 precious books, manuscripts and musical scores, dating from the 15th to the 20th century. A selection of a hundred of these works will be part of a travelling preview exhibition in Monaco, New York, Hong Kong and London during the summer and autumn of 2015. The first part of the library will be auctioned in Paris on 11 December at the Hôtel Drouot, by Antoine Godeau. This first sale will offer a stunning selection of one hundred and fifty works of literary interest spanning six centuries, from the first edition of St Augustine’s Confessions, printed in Strasbourg circa 1470, to William Burroughs’ Scrap Book 3, published in 1979. The thematic sales which are to follow in 2016 and 2017 will feature not only literary works, the core of the collection, but also books on botany, gardening, music and the exploration of major philosophical and political ideas. -

Jean Cocteau

Jean Cocteau: An Inventory of His Papers in the Carlton Lake Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Cocteau, Jean, 1889-1963 Title: Carlton Lake Collection of Jean Cocteau Papers Inclusive Dates: 1905-1959 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1910-1928) Quantity: 11 boxes (4.62 linear feet), 6 oversize folders (osf), 1 bound volume (bv), and 1 galley folder (gf) Abstract: The early personal and professional life of the French poet, novelist, artist, playwright, and filmmaker Jean Cocteau is documented in this collection of manuscripts, correspondence, personal papers, notebooks, drawings, financial and legal documents, and third-party papers, drawn largely from his personal archives. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-04960 Language: All materials are in French. Note: We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which provided funds for the processing and cataloging of this collection. Access: Open for research. Permission from copyright holder must accompany photoduplication requests for Jean Cocteau materials. Administrative Information Acquisition: Gifts and purchases, 1966, 1969, 1973, 1977, 1987, 1997 (G846, G2793, G2966, R5180, R5374, R5883, R7748, G10713) Processed by: Monique Daviau, Catherine Stollar, Richard Workman, 2004 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Cocteau, Jean, 1889-1963 Manuscript Collection MS-04960 Biographical Sketch Jean Cocteau, one of the most versatile creative artists of the twentieth century, achieved celebrity as poet, playwright, journalist, novelist, artist, and filmmaker. At the time of his death he was perhaps the best-known French literary figure outside of France. Born Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau on July 5, 1889, he was a child of affluence, particularly through the Lecomtes on the maternal side of his family. -

The Performance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance, 1917

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Summer 8-1-2012 The eP rformance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance, 1917-1925 Amanda Holly Beresford Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Beresford, Amanda Holly, "The eP rformance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance, 1917-1925" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1027. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1027 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Art History and Archaeology The Performance of Art: Picasso, Léger, and Modern Dance 1917-1925 by Amanda Holly Beresford A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri Copyright by Amanda Holly Beresford 2012 Acknowledgements My thanks are due to the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Washington University for the award of a Research Travel grant, which enabled me to travel to Paris and London in the summer of 2010 to undertake research into the -

Je Me Tais Et J'attends… » Lettres Inédites À Jean Cocteau

« JE ME TAIS ET J’ATTENDS… » LETTRES INÉDITES À JEAN COCTEAU (1916 ?-1944) ET À MADAME EUGÉNIE COCTEAU, SA MÈRE (1922-1927) Correspondances présentées par Anne Verdure-Mary* Édition établie et annotée par Anne Kimball** n 2015 la Bibliothèque nationale de France fait l’acquisition d’un ensemble E de quatorze lettres de Max Jacob à Jean Cocteau passé en vente chez Artcu- rial à la fin de l’année précédente. Intégré aux collections de la bibliothèque sous la cote NAF 28812, ce lot constitue un complément au fonds Max Jacob-collection * Anne Verdure-Mary, archiviste-paléographe et Docteur en littérature, est conservateur au dépar- tement des Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, responsable de plusieurs fonds d’auteurs contemporains, dont le Fonds Max Jacob-Collection Gompel Netter. Elle a été commis- saire des expositions « Boris Vian » (2011) et « Edmond Jabès. L’exil en partage » (2012) à la BnF, et a publié l’ouvrage Drame et pensée. La place du théâtre dans l’œuvre de Gabriel Marcel (éd. Champion, 2015), ainsi que plusieurs articles en rapport avec cet auteur. Elle a édité les lettres de Max Jacob à Roger Lannes (« Lettres de Max Jacob à Roger Lannes. La tige et l’orchidée (1935- 1943), suivies de “Hommage à Max Jacob” par Roger Lannes », CMJ, 2012). ** Anne Kimball, docteur ès lettres de l’Université du Wisconsin, a enseigné dans les Univer- sités de Mount Holyoke et Randolph-Macon (Virginie). Nommée doyenne de la faculté à Randolph-Macon, puis titulaire de la chaire Dana de littérature, des bourses Fulbright l’ont aidée à publier plusieurs volumes de lettres de Max Jacob : Max Jacob écrit (PUR, 2015), Max Jacob-Cocteau, Correspondance, Lettres à Jean Paulhan (Paris-Méditerranée, 2000 et 2005), Lettres à Nino Frank (Peter Lang, 1989), Lettres à Pierre Minet (Calligrammes, 1988), Lettres à Marcel Jouhandeau (Droz, 1979 ; épistolaire complété en 2002 par les lettres de Marcel Jouhandeau à Max Jacob). -

Papers of David Arkell (Ark): Collection Level

PAPERS OF DAVID ARKELL: COLLECTION LEVEL DESCRIPTION AND BOX LIST Title: Papers of David Arkell Reference: ARK Dates of creation: 1849-1997 Extent: 23 boxes and 23 volumes. Name of creator: Arkell, David, 1913-1997, journalist, translator, biographer and ‘literary sleuth’. Biographical History Journalist, translator, biographer and ‘literary sleuth’, David Arkell was born on 23 August 1913 in Weybridge, Surrey. His parents were both involved in the arts: his father, Reginald, was an author and his mother Elizabeth (née Evans) an actress. Some of his earliest childhood memories involved visits to theatres where his mother was playing, and he made his own acting début at the age of seven, playing Peter Cratchit in a Charles Dickens Birthday Matinée at the Lyric Theatre in February 1921, alongside his mother and Ellen Terry. He grew up in London, attending Colet Court and St Paul’s School, which he left in 1930. He began his journalistic career as a reporter on local newspapers in Newcastle upon Tyne during 1932-4, contributing dramatic reviews and articles on literary and dramatic themes. He moved on to become a columnist for various London papers and magazines, including the London Opinion and Men Only, for which he wrote light-hearted articles, many on the subject of France and the French. Arkell was fluent in French; his mother Elizabeth, whose father came from Jersey, was educated in Belgian convent schools and brought up bilingual; she was keen for her son also to be proficient in French. He put this to good use, when in the late 1930s he moved to Paris and became French correspondent for the Continental Daily Mail.