Robert Bage on Poverty, Slavery and Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Boys with a Bladder by Joseph Wright of Derby

RCEWA – Two Boys with a Bladder by Joseph Wright of Derby Statement of the Expert Adviser to the Secretary of State that the painting meets Waverley criteria two and three. Further Information The ‘Applicant’s statement’ and the ‘Note of Case History’ are available on the Arts Council Website: www.artscouncil.org.uk/reviewing-committee-case-hearings Please note that images and appendices referenced are not reproduced. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Brief Description of item(s) • What is it? A painting by Joseph Wright of Derby representing two boys in fancy dress and illuminated by candlelight, one of the boys is blowing a bladder as the other watches. • What is it made of? Oil paint on canvas • What are its measurements? 927 x 730 mm • Who is the artist/maker and what are their dates? Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797) • What date is the item? Probably 1768-70 • What condition is it in? Based upon a viewing of the work by the advisors and conservators, the face and costumes of the two boys are in good condition. However, dark paint throughout the background exhibits widespread retouched drying cracking and there are additional areas of clumsy reconstruction indicating underlying paint losses. 2. Context • Provenance In private ownership by the 1890s; thence by descent The early ownership of the picture, prior to the 1890s, is speculative and requires further investigation. The applicant has suggested one possible line of provenance, as detailed below. It has been mooted that this may be the painting referred to under a list of sold candlelight pictures in Wright’s account book as ‘Boys with a Bladder and its Companion to Ld. -

Joseph Wright

Made in Derby 2018 Profile Joseph Wright Derby’s most celebrated artist is known the world over. Derby Museums is home to the world’s largest collection of works by the 18th century artist. Joseph Wright of Derby is acknowledged officially as an “English landscape and portrait painter”. But his fame lies in being acclaimed as "the first professional painter to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution", by experts. Candlelight, the contrast of light and dark, known as the chiaroscuro effect, and the birth of science out of the previously held beliefs of alchemy all feature in his works. The inspiration for Wright’s work owes much to meetings of the Lunar Society, a group of scientists and industrialists living in the Midlands, which sought to reconcile science and religion during the Age of Enlightenment. Wright was born in Iron Gate – where a commemorative obelisk now stands –in 1734, the son of Derby’s town clerk John Wright. He headed to London in 1751 to study to become a painter under Thomas Hudson but returned in 1753 to Derby. Wright went back to London again for a further period of training before returning to set up his own business in 1757. He married, had six children – one of whom died in infancy, son John, died aged 17 but the others survived to live full lives. In 1773, he took a trip to Italy for almost two years and this became the inspiration for some of his work featuring Mount Vesuvius. Stopping off to work for a while in Bath as a portrait painter, he finally returned to Derby in 1777, where he remained until his death at 28 Queen Street in 1797. -

Burntwood Town Council

The Old Mining College Centre Queen Street Chasetown BURNTWOOD WS7 4QH Tel: 01543 677166 Email: [email protected] www.burntwood-tc.gov.uk Our Ref: GH/JM 09 March 2021 To: All Members of the Planning Advisory Group Councillors Westwood [Chairman], Bullock [Vice-Chairman], Flanagan, Greensill, Norman and R Place S Oldacre, J Poppleton, S Read, K Whitehead and S Williams Dear Member PLANNING ADVISORY GROUP The Planning Advisory Group will meet via a Virtual Meeting on Tuesday 16 March 2021 at 6:00 pm to consider the following business. Councillors and members of the public can join the meeting by using Zoom [Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83095403221?pwd=Z2k3bDc4dFlBSnhzVGQ3RDNVY3dFUT09 Meeting ID: 830 9540 3221, Passcode: 582384]. If you have any queries, please contact the Town Clerk [[email protected]]. Yours sincerely Graham Hunt Town Clerk As part of the Better Burntwood Concept and to promote community engagement, the public now has the opportunity to attend and speak at all of the Town Council’s meetings. Please refer to the end of the agenda for details of how to participate in this meeting. AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS AND DISPENSATIONS To receive declarations of interests and consider requests for dispensations. 3. MINUTES To approve as a correct record the Minutes of the Meeting of the Planning Advisory Group held on 10 February 2020 [Minute No. 1-8] [ENCLOSURE NO. 1]. 4. INTRODUCTIONS AND TERMS OF REFERENCE To receive and note the Terms of Reference for the Planning Advisory Group [ENCLOSURE NO. -

The Granary Fisherwick Road | Lichfield | Staffordshire

The Granary Fisherwick Road | Lichfield | Staffordshire THE GRANARY Stunning barn conversion of nearly 4,000ft2, steeped with history and amazing features, hidden in a private development of six country homes down a three quarter mile private driveway. The property has four bedrooms and five reception rooms including a very impressive drawing room with full height ceilings and gallery landing. Step Inside The Granary Converted in 1990 and said to be the tallest remaining barn in Staffordshire, the height of this Grade ll listed property offers a sense of grandeur as one enters the full height drawing room with flagstone floors and welcoming inglenook fireplace. A gated driveway leads to the integral double garage with the property enjoying two small garden areas, the former is perfect for entertaining with pergola and lantern lighted barbeque area. The latter is an easily maintained lawn area. The original barn was built in 1360 and unfortunately burnt down but it was rebuilt in 1540 and we still retain some of the original wall. There are Tudor roses imprinted into the beams and these little details add to the sense of times gone by, it really does feel like an old barn with an immense history. A spiral staircase leads from the family room up to a galleried upper floor office / snug. The galleried landing offers an additional area to relax and provides access to the show stopping dining room with vaulted beam ceiling overlooking the drawing room. A great gym/dance studio on the ground floor with window was originally part of the garage block and could be converted to a number of uses. -

The Derby School Register, 1570-1901

»;jiiiiliiiili^ 929.12 D44d 1275729 'I ^BNHAUOG^r CiOUi^H-OTiOM ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 01795 1531 . ^^-•^ THE DERBY SCHOOL REGISTER, I ^70-1901 /// prepanxtio)! : *• History of Derby School from the Earliest Times to the Present Day." : THE DERBY SCHOOL REGISTER. 1 5'7o-i90i . Edited by B. TACCHELLA, Assiiiaiit Master of Derby Sehool. LONDON BEMROSE & SONS, Limited, 4, Snow Hill ; and Derby, 1902. Sic *ffDeur\? Ibowe Beinrose, Ikt., ®.H)., THE PATRON OF DERBYSHIRE LITERATURE, THIS REGISTER OF DERBY SCHOOL IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, AS A SLIGHT ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF HIS GENIAL ENCOURAGEMENT AND INVALUABLE ASSISTANCE DURING ITS COMPILATION. ^ PREFACE. ,__ NO work is more suited to perpetuate the fame and traditions of an ancient scliool, and to foster the spirit of brother- hood among the succeeding generations of its alumni, than a Register recording the proud distinctions or the humble achievements of those who have had the honour of belonging to it. To do this, effectually a register ought to be complete in all its parts, from the first clay the school opened its doors ; and it is evident that such a work could only be the result of a continuous purpose, coeval with the school itself. Unfortunately that task has been deferred from century to century, and has become harder in proportion to its long post- ponement. But is this a. reason why it should not at length be attempted? As the usefulness, or, to speak more correctly, the necessity of such an undertaking has in these latter times become more and more apparent at Derby School, and as procrastination only makes matters worse, the editor decided some years ago to face the difficulty and see what could be done. -

Matthew Boutlon and Francis Eginton's Mechanical

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository MATTHEW BOULTON AND FRANCIS EGINTON’S MECHANICAL PAINTINGS: PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION 1777 TO 1781 by BARBARA FOGARTY A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The mechanical paintings of Matthew Boulton and Francis Eginton have been the subject of few scholarly publications since their invention in the 1770s. Such interest as there has been has focussed on the unknown process, and the lack of scientific material analysis has resulted in several confusing theories of production. This thesis’s use of the Archives of Soho, containing Boulton’s business papers, has cast light on the production and consumption of mechanical paintings, while collaboration with the British Museum, and their new scientific evidence, have both supported and challenged the archival evidence. This thesis seeks to prove various propositions about authenticity, the role of class and taste in the selection of artists and subjects for mechanical painting reproduction, and the role played by the reproductive process’s ingenuity in marketing the finished product. -

The Derbyshire General Infirmary and The

Medical History, 2000, 46: 65-92 The Derbyshire General Infirmary and the Derby Philosophers: The Application of Industrial Architecture and Technology to Medical Institutions in Early-Nineteenth-Century England PAUL ELLIOTT* Though there have been various studies ofhospital architecture, few have examined in detail the application of industrial technology to medical institutions in the Enlightenment and early-nineteenth-century periods.' This paper tries to rectify this by offering a case study of one hospital, the Derbyshire General Infirmary (1810), where, principally under the inspiration of the cotton manufacturer, William Strutt FRS (1756-1830), a deliberate attempt was made to incorporate into a medical institution the latest "fireproof' building techniques with technology developed for * Paul Elliott, School of Geography, University of medicine in Manchester, 1788-1792: hospital Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 reform and public health services in the early 2RD. industrial city', Med. Hist., 1984, 28: 227-49; F N L Poynter (ed.), The evolution of hospitals in I am grateful to Desmond King-Hele, Jonathan Britain, London, Pitman Medical, 1968; L Prior, Barry, Anne Borsay, William F Bynum and John 'The architecture of the hospital: a study of Pickstone for their helpful criticisms, and to John spatial organisation and medical knowledge', Br Pickstone for sending me copies of a couple of J. Sociol., 1988, 39: pp. 86-113; H Richardson his papers. (ed.), English hospitals, 1660-1948: a survey of their architecture and design, Swindon, Royal 'B Abel-Smith, The hospitals 1880-1948: a Commission on the Historical Monuments of study in social administration in England and England, 1998; E M Sigsworth, 'Gateways to Wales, London, Heinemann, 1964; A Berry, death? Medicine, hospitals and mortality, 'Patronage, funding and the hospital patient c. -

Whittington & Fisherwick Parish Plan Summary Document

Whittington & Fisherwick Planning for the Future Parish Plan Summary Document 2013 J14797 Parish Plan Final Version Oct 2013.indd 44-1 31/10/2013 10:49 Whittington and Fisherwick – Planning for the Future Parish Plan Consultation Document 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Parish Plan Summary 4 Whittington and Fisherwick Parish Plan 7 Preface ................................................................................................................................................ 7 The Parish Plan ................................................................................................................................... 7 Annexes .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1. Introduction and Snapshot of Whittington and Fisherwick 8 2. Why we need a Parish Plan 10 The Parish Plan 12 1. Housing 12 2. Maintaining and Enhancing our Community Assets 16 Introductory ...................................................................................................................................... 16 NHS based Medical Services .......................................................................................................... 16 Associated Services ......................................................................................................................... 16 Community Organisations and Assets ........................................................................................... 17 Commercial Linkages ..................................................................................................................... -

The Shropshire Enlightenment: a Regional Study of Intellectual Activity in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries

The Shropshire Enlightenment: a regional study of intellectual activity in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries by Roger Neil Bruton A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham January 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The focus of this study is centred upon intellectual activity in the period from 1750 to c1840 in Shropshire, an area that for a time was synonymous with change and innovation. It examines the importance of personal development and the influence of intellectual communities and networks in the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge. It adds to understanding of how individuals and communities reflected Enlightenment aspirations or carried the mantle of ‘improvement’ and thereby contributes to the debate on the establishment of regional Enlightenment. The acquisition of philosophical knowledge merged into the cultural ethos of the period and its utilitarian characteristics were to influence the onset of Industrial Revolution but Shropshire was essentially a rural location. The thesis examines how those progressive tendencies manifested themselves in that local setting. -

Wigginton and Hopwas Parish Council

Wigginton and Hopwas Parish Council. Chairman of the Parish Council Councillor Keith Stevens Mrs. M. Jones, Clerk, Wigginton and Hopwas Parish Council, 50, Cornwall Avenue Tamworth, Staffordshire. B78 3YB 01827 50230 [email protected] 14/02/13 Mrs Clare Egginton Principal Development Plans Officer Lichfield District Council District Council House Frog Lane Lichfield WS13 6YU Dear Clare Re: Application for Designation of a Neighbourhood Area At the Parish Council meeting held on 7th February 2013 it was resolved that the Parish Council should apply to Lichfield District Council to request that the Parish of Wigginton and Hopwas be designated a Neighbourhood Area. Accordingly as a Parish Council and relevant body for the purposes of section 61G of the 1990 Act we enclose a map identifying the Parish of Wigginton and Hopwas which we believe is an area appropriate to be designated a Neighbourhood Area. The Parish of Wigginton and Hopwas is predominately rural, comprising the villages of Hopwas and Wigginton, the hamlet of Comberford, and several farms and outlying properties. It is bordered on the south by the town of Tamworth, which is used for services by many residents. The Parish Council believes that the development of a Neighbourhood Plan through consultation with residents is appropriate for providing for the needs of the communities which it serves. Yours sincerely Mrs M Jones Mrs M Jones Clerk to Wigginton and Hopwas Parish Council Wigginton & Hopwas Parish Harrllastton CP Ellfforrd CP Whiittttiingtton CP Fiisherrwiick CP Thorrpe Consttanttiine CP Wiiggiintton and Hopwas CP Swiinffen and Packiingtton CP Hiintts CP Fazelley CP Reproduced from The Ordnance Survey Mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Offices (C) Crown Copyright : License No 10001776¯5 Dated 2013 Key Map supplied by Lichfield District Council Lichfield District Boundary Wigginton & Hopwas Parish. -

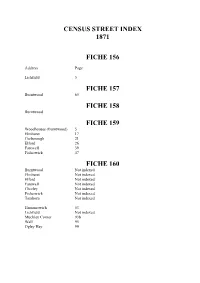

Census Street Index 1871

CENSUS STREET INDEX 1871 FICHE 156 Address Page Lichfield 5 FICHE 157 Burntwood 65 FICHE 158 Burntwood FICHE 159 Woodhouses (Burntwood) 5 Elmhurst 17 Curborough 21 Elford 26 Farewell 39 Fisherwick 47 FICHE 160 Burntwood Not indexed Elmhurst Not indexed Elford Not indexed Farewell Not indexed Chorley Not indexed Fisherwick Not indexed Tamhorn Not indexed Hammerwich 53 Lichfield Not indexed Muckley Corner 93b Wall 95 Ogley Hay 99 FICHE 160 OGLEY HAY Address Page Address Page Ogley Hay 88-127 New Road 104 Bells Row 99 Brick Hill Farm, Chester Rd 104 Church Hill 99 Chester Road 104-117 Shoulder of Mutton Inn 99 Wheatsheaf 113 Hope Cottage 100 Miners Arms 114 School House 103 The Square 117 Vicarage 103 Burntwood Road 121 Wolverhampton Road 122-127 FICHE 162 Address Page Ogley Hay 4-17 Address Page Walsall Road 4 Spring Hill 11 Watling Street Road 4 Walsall Road 11 Ogley Road 4-6 Barrack Lane 11 Fox Row 6 Warren House Farm 12A Walsall Road 7-9 Lock House 12 Hilton Lane 9 Weeford 16 Rowleys Cottage 10 Thickbroom 22 Rowleys Farm 10 Packington 23 Cranbrook Farm 10 Swinfen 25 Walsall Road 10 Shenstone 30-49,59-68 Spring Hill Farm 11 FICHE 163 Address Page Address Page Wood End 50 Friezeland Lane 65 Footheley 53-59 The Anchor Inn, Chester Rd. 68 Cranebrook 59 Catshill 68 Pouk Lane 59 Chester Road 68 Whiteacres Lane 59 Shire Oak Cottages 68 Cartersfield Lane 59 The Royal Oak 68 Sandhills 60 Hodgkins Row 71 Shire Oak 62 Robinson’s Row 72 Gilpin’s Houses 62 Clark’s Row 73 Friezeland 64 Ogley Lane 73 Williams Row 73 FICHE 164 OGLEY HAY (cont) Address -

Superfast Staffordshire Live Cabinet List

SUPERFAST STAFFORDSHIRE LIVE CABINET LIST Cabinet Name Location District Parish S/O The Cash Store, Ashbrook East Staffordshire Abbots Bromley 2 Abbots Bromley Lane, Abbots Bromley Borough Council High St, O/S Sycamore House, East Staffordshire Abbots Bromley 3 Abbots Bromley Abbots Bromley Borough Council Tuppenhurst Lane, S/O 2 Lichfield District Armitage with Armitage 1 Proctor Road, Rugeley Council Handsacre S/O 73 Uttoxeter Road, Hill Lichfield District Armitage 3 Mavesyn Ridware Ridware, Rugeley Council Opp 65 Brook End, Longdon, Lichfield District Armitage 4 Longdon Rugeley Council Opp Rugeley Road, Armitage, Lichfield District Armitage with Armitage 5 Rugeley Council Handsacre Opp 31 Lichfield Road, Lichfield District Armitage with Armitage 6 Armitage, Rugeley Council Handsacre Lichfield District Armitage with Armitage 7 S/O 1 Station Dr Rugeley Council Handsacre Lichfield District Armitage with Armitage 8 S/O 6 Hood Lane Armitage Council Handsacre S/O 339 Ash Bank Road, Staffordshire Ash Bank 1 Werrington Washerwall Lane Moorlands District Staffordshire S/O 160 Ash Bank Road, New Ash Bank 2 Moorlands District Werrington Road Council Staffordshire S/O 1 Moss Park Ave, Stoke-on- Ash Bank 3 Moorlands District Werrington Trent Council Staffordshire S/O 425 Ash Bank Road, Ash Bank 5 Moorlands District Werrington Johnstone Avenue Council S/O 1 Chatsworth Drive, Salters Staffordshire Ash Bank 6 Werrington Lane Moorlands District S/O 1 Brookhouse Lane, Ash Bank 7 Werrington Road, Stoke On Stoke City Council Trent Staffordshire S/O 51