Transcript S01E07

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Hirta) (UK) ID N° 387 Bis Background Note: St. Kilda

WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION Saint Kilda (Hirta) (UK) ID N° 387 Bis Background note: St. Kilda was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1986 under natural criteria (iii) and (iv). At the time IUCN noted that: The scenery of the St. Kilda archipelago is particularly superlative and has resulted from its volcanic origin followed by weathering and glaciation to produce a dramatic island landscape. The precipitous cliffs and sea stacks as well as its underwater scenery are concentrated in a compact group that is singularly unique. St. Kilda is one of the major sites in the North Atlantic and Europe for sea birds with over one million birds using the Island. It is particularly important for gannets, puffins and fulmars. The maritime grassland turf and the underwater habitats are also significant and an integral element of the total island setting. The feral Soay sheep are also an interesting rare breed of potential genetic resource significance. IUCN also noted: The importance of the marine element and the possibility of considering marine reserve status for the immediate feeding areas should be brought to the attention of the Government of the UK. The State Party presented a re-nomination in 2003 to: a) seek inclusion on the World Heritage List for additional natural criteria (i) and (ii), as well as cultural criteria (iii), (iv), and (v), thus re-nominating St. Kilda as a mixed site; and b) to extend the boundaries to include the marine area. _________________________________________________________________________ 1. DOCUMENTATION i) IUCN/WCMC Data Sheet: 25 references. ii) Additional Literature Consulted: Stattersfield. -

The Welfare Status of Salmon Farms and Companies in Scotland Contents

Ending cruelty to Scotland’s animals The welfare status of salmon farms and companies in Scotland Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Our approach 3 3 The salmon farm league table 4 4 The salmon farming company league table 6 5 Performance on key animal welfare criteria 7 6 Conclusions 10 7 Annex 1: The salmon farm league table 11 8 Annex 2: Methodology for assessing the welfare status of Scotland’s salmon farms 20 9 Annex 3: Methodology for assessing the welfare status of companies 21 10 References 21 1 Introduction There are serious fish welfare concerns on Scotland’s based entirely on publicly available data, most of salmon farms. We believe that these issues need which is published via the multi-government agency to be urgently addressed so that fish involved in initiative Scotland’s Aquaculture. Short of visiting salmon farming live good lives that are free from and assessing every salmon farm in the country, this suffering. To deliver this, a new approach needs to is the only objective means by which stakeholders be taken by the industry, which puts high standards can assess relative welfare performance. of welfare at the front and centre of everything, We hope that the results of this analysis will act as a meeting demands by consumers and the Scottish reminder to the industry, government, stakeholders, public. and the public of the importance of fish welfare, and This report aims to encourage this transition that, alongside other initiatives in this field, it will by assessing the welfare performance of every encourage improvement of fish welfare on salmon salmon farm and every salmon farming company farms in Scotland. -

A Guided Wildlife Tour to St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides (Gemini Explorer)

A GUIDED WILDLIFE TOUR TO ST KILDA AND THE OUTER HEBRIDES (GEMINI EXPLORER) This wonderful Outer Hebridean cruise will, if the weather is kind, give us time to explore fabulous St Kilda; the remote Monach Isles; many dramatic islands of the Outer Hebrides; and the spectacular Small Isles. Our starting point is Oban, the gateway to the isles. Our sea adventure vessels will anchor in scenic, lonely islands, in tranquil bays and, throughout the trip, we see incredible wildlife - soaring sea and golden eagles, many species of sea birds, basking sharks, orca and minke whales, porpoises, dolphins and seals. Aboard St Hilda or Seahorse II you can do as little or as much as you want. Sit back and enjoy the trip as you travel through the Sounds; pass the islands and sea lochs; view the spectacular mountains and fast running tides that return. make extraordinary spiral patterns and glassy runs in the sea; marvel at the lofty headland lighthouses and castles; and, if you The sea cliffs (the highest in the UK) of the St Kilda islands rise want, become involved in working the wee cruise ships. dramatically out of the Atlantic and are the protected breeding grounds of many different sea bird species (gannets, fulmars, Our ultimate destination is Village Bay, Hirta, on the archipelago Leach's petrel, which are hunted at night by giant skuas, and of St Kilda - a UNESCO world heritage site. Hirta is the largest of puffins). These thousands of seabirds were once an important the four islands in the St Kilda group and was inhabited for source of food for the islanders. -

St Kilda World Heritage Site Management Plan 2012–17 Title Sub-Title Foreword

ST KILDA World Heritage Site Management Plan 2012–17 TITLE Sub-title FOREWORD We are delighted to be able to present the revised continuing programme of research and conservation. Management Plan for the St Kilda World Heritage Site The management of the World Heritage Site is, for the years 2012-2017. however, a collaborative approach also involving partners from Historic Scotland, Scottish Natural St Kilda is a truly unique place. The spectacular Heritage, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and the Ministry of scenery and wildlife, both on land and in the seas Defence. As custodians of St Kilda, all of the partners surrounding the islands, the archipelago’s isolation and should be thanked for their excellent work over recent inaccessibility, and the evidence, abundant for all to years, and the new Management Plan will continue to see, of the people that made these islands their home, build on these efforts. make St Kilda truly exceptional. The very nature of St Kilda means that the challenges In this respect, St Kilda showcases Scotland to the are different to those of other World Heritage Sites. world by displaying the most important features of our By identifying and addressing key short and medium heritage, our rich natural and cultural traditions, and our term issues around protection, conservation and awe inspiring landscapes and scenery. management, the Management Plan aims to embrace these challenges, and sets out a thirty year vision for the It is therefore of no surprise that St Kilda has been property, ensuring that the longer-term future of St Kilda designated as a World Heritage Site for both its cultural is properly considered. -

The Salmon Farm Monitor

The Salmon Farm Monitor th PRESS RELEASE – IMMEDIATE USE – 25 APRIL 2004 Scotland’s Toxic Toilets Revealed “Filthy Five” flood Scottish waters with chemical wastes Exclusive information obtained by the Salmon Farm Protest Group (SFPG) reveals that there are now ca. 1,400 licences for the use of Azamethiphos, Cypermethrin, Dichlorvos, Emamectin Benzoate, Formalin and Teflubenzuron on Scottish salmon, cod and halibut farms [1]. This chemical cocktail includes carcinogens, hormone disrupting compounds (“gender benders”) and marine pollutants [2]. Find out where Scotland’s “Toxic Toilets” are via The Salmon Farm Monitor: www.salmonfarmmonitor.org Responding to a request for information under the Freedom of Environmental Information Regulations, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency concede that since 1998 they have issued 311 licences for Cypermethrin, 282 for Azamethiphos, 212 for Teflubenzuron and 211 for Emamectin Benzoate (1016 in total). According to SEPA “around 20” licences are also still outstanding for the banned carcinogen Dichlorvos and the Scottish Executive admitted last year that SEPA has issued a further 360 licences for the use of Formalin since 1998 [3]. Special Areas of Conservation (as protected under the EC Habitats Directive) subject to chemical discharges include the Moray Firth, Firth of Lorne, Loch Creran, Loch Laxford, Loch Roag, Loch Duich and Loch Alsh. Other lochs include Ainort, Arnish, Broom, Carron, Diabaig, Erisort, Ewe, Fyne, Glencoul, Grimshader, Harport, Kanaird, Kishorn, Leven, Linnhe, Little Loch Broom, Maddy, Nevis, Portree, Seaforth, Shell, Sligachan, Snizort, Spelve, Striven, Sunart and Torridon. Of the 1016 licences issued since 1998 for Azamethiphos, Cypermethrin, Emamectin Benzoate and Teflubenzuron the biggest culprits – the “Filthy Five” – are Marine Harvest (Scotland) Ltd (152), Scottish Seafarms Ltd (139), Stolt Sea Farms Ltd (82), Lighthouse of Scotland Ltd/Lighthouse Highland Ltd (81) and Mainstream Scotland Ltd (69). -

The Development of Ornithology on St Kilda

á á A St Kildan and his catch of fulmars. (Photograph N. Rankin) tt, Natural Environment Research ACouncil Institute of TerrestrialEcology Birds of St Kilda M P. Harris S Murray å 1 INSMUTE OF TERRESTRIALECOLOGY LIBRARY !,3ERVICE I EDIN3ti RGH LAB 0 RA TO ::.i;ES BUSH ESTATE, PEMCUi'K 1 m0 I nTHLANEH25 00 B London: Her Majesty's StationeryOffice INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY © Crown copyright 1989 LIBRARY First published in 1978 by SERVICE Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Second impression with minor corrections 1989 7 MAR 1990 ISBN 0 11 701423 0 p COVER PHOTOGRAPHS (M. P. Harris) StIt k--1/4 %AS O Right Puffin ccuxeciitt 04 t :9) Top left Boreray and the Stacs Lower left Gannets Half title A St Kildan and his catch of fulmars (Photograph N. Rankin) Frontispiece Top section of the main gannet cliff below the summit of Boreray, July 1975 (Photograph M. P. Harris) The INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY is one of 15 component and grant-aided research organizations within the Natural Environment Research Council. The Institute is part of the Terrestrial and Freshwater Sciences Directorate, and was established in 1973 by the merger of the research stations of the Nature Conservancy with the Institute of Tree Biology. It has been at the forefront of .ecological research ever since. The six research stations of the Institute provide a ready access to sites and to environmental and ecological problems in any part of Britain. In addition to the broad environmental knowledge and experience expected of the modern ecologist, each station has a range of special expertise and facilities. -

History, Economy and Society Are Inevitably Linked to the Degree of Contact with the Outside World and the Manner in Which That Contact Takes Place.1 St Kilda

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2010; 40:368–73 Paper doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2010.410 © 2010 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Survival of the ttest: a comparison of medicine and health on Lord Howe Island and St Kilda P Stride Physician, Redcliffe Hospital, Redcliffe, Queensland, Australia ABSTRACT Lord Howe Island and the St Kilda archipelago have many similarities, Correspondence to P Stride, yet their communities had totally disparate outcomes. The characteristics of the Redcliffe Hospital, Locked Bag 1, two islands are compared and contrasted, and it is hypothesised that the Redcliffe, Queensland, differences in health and diseases largely explain the success of one society and Australia 4020 the failure of the other. tel. +617 3256 7980 KEYWORDS Lord Howe Island, neonatal tetanus, remote e-mail Infectious diseases, [email protected] islands, St Kilda DECLaratION OF INTERESTS No conflict of interests declared. INTRODUCTION Oceanic islands are often isolated, and their history, economy and society are inevitably linked to the degree of contact with the outside world and the manner in which that contact takes place.1 St Kilda The fortunate traveller who has visited both Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean and the island archipelago of St Inverness Kilda in the Outer Hebrides will be struck by the many Barra Scotland common features of these two remote islands; yet today one is a thriving society and the other was evacuated as a non-sustainable society in 1930. This paper analyses Oban medical provision, health and outcomes on both islands in the period from 1788 when Lord Howe Island was Brisbane Norfolk Island discovered to 1930 when St Kilda was evacuated. -

THE HEBRIDES Explore the Majestic Beauty of the Hebrides Aboard the Ocean Nova 11Th to 18Th May 2019 Gannet in Flight

ISLAND HOPPING IN THE HEBRIDES Explore the majestic beauty of the Hebrides aboard the Ocean Nova 11th to 18th May 2019 Gannet in flight St Kilda Exploring the island of Barra Standing Stones of Callanish, Isle of Lewis ords do not do justice to the spectacular The Itinerary beauty, rich wildlife and fascinating history Isle of Embark the Ocean Nova W St Kilda Lewis Day 1 Oban, Scotland. of the Inner and Outer Hebrides which we will Stornoway this afternoon. Transfers will be provided from OUTER Shiant Islands HEBRIDES Glasgow Central Railway Station and Glasgow explore during this expedition aboard the Ocean Canna International Airport at a fixed time. Enjoy Nova. One of Europe’s last true remaining Barra Loch Scavaig Mingulay SCOTLAND Welcome Drinks and Dinner as we sail this evening. wilderness areas affords the traveller a marvellous Lunga Iona Oban Colonsay Jura Day 2 Barra & Mingulay. This morning we will island hopping journey through stunning scenery INNER HEBRIDES land on Barra which is near the southern tip of accompanied by spectacular sunsets and prolific the Outer Hebrides and visit Castlebay which birdlife. With our naturalists and local guides and curves around the barren rocky hills of a beautiful our fleet of nimble Zodiacs we are able to visit wide bay. Here we find the 15th century Kisimul Castle, seat of the Clan Macneil and a key some of the most remote and uninhabited islands that surround the Scottish coast defensive stronghold situated on a rock in the including St Kilda and Mingulay as well as the small island communities of bay. -

Sea-And-Coast.Pdf

Sea and Coast Proximity to the sea has a huge influence on the biological richness of Wester Ross. The area has a long, varied and very beautiful coastline, ranging from exposed headlands to deeply indented, extremely sheltered sea lochs. The Wester Ross sea lochs are true fjords, with ice-scoured basins separated from each other and from the open sea by relatively narrow and shallow sills, and in Scotland are features found only on the west coast. The coast supports a wide variety of habitats including coastal heaths and cliffs, rocky shores, sandy beaches, sand dunes and salt marshes. Our cliffs and islands are home to large numbers of seabirds, which feed at sea and come ashore to nest and rear their young, while harbour (common) seals produce their pups on offshore rocks and skerries. Turnstone and Ringed plover frequent the mouth of the Sand river in winter. Tracks of otter can often be seen in the sands nearby. Underwater, the special habitats greatly enhance the marine biodiversity of the area. Inside the quiet, sheltered basins, conditions on the seabed are similar to those in the very deep sea off the continental shelf, especially when a layer of peaty fresh or brackish water floats on the surface after rain, cutting out light and insulating the water below from marked temperature changes. Here, mud and rock at relatively shallow depths support animals which are more typical of very deep water. By contrast, strong water currents in the tidal narrows and rapids nourish a wide range of animals, and communities here include horse mussel reefs, flame shell reefs, brittlestar beds and maerl (calcareous seaweed) beds. -

Br 12-09-09 Things to Do

Text and pictures about a rather special place in Scotland St Kilda features & fractions & fate Bernd Rohrmann St Kilda - Features & Fate - Essay by BR - p 2 Bernd Rohrmann (Melbourne/Australia) St Kilda Islands in Scotland - Features & Fate May 2015 In April 2015 I visited Hirta in St Kilda. Therefore I have created this essay, in which its main features and its fate are described, enriched by several maps and my pictures. Location The Scottish St Kilda islands are an isolated archipelago 64 kilometres west-northwest of North Uist in the North Atlantic Ocean, which belongs to the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom; the other islands are Dùn, Soay and Boreray. Name The origin of the name St Kilda is still debated. Its Gaelic name, referring to the island Hirta, is "Hiort", its Norse name possibly "Skildir". The meaning, in Gaelic terms, may be "westland". The Old Norse name for the spring on Hirta, "Childa", is also seen as influence. The "St" in St Kilda does not refer to any person of holiness. One interpretatrion says that it is a distortion of the Norse naming. The earliest written records of island life date from the Late Middle Ages, referring to Hirta. Aerial view 1 St Kilda - Features & Fate - Essay by BR - p 3 Landscape The archipelago represents the remnants of a long-extinct ring volcano rising from a seabed plateau approximately 40 metres below sea level. The landscape is dominated by very rocky areas. The highest point in the archipelago is on Hirta, the Conachair ('the beacon') at 430 metres. -

The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019

SCOTTISH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2019 No. 56 FISHERIES RIVER SEA FISHERIES The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019 Made - - - - 18th February 2019 Laid before the Scottish Parliament 20th February 2019 Coming into force - - 1st April 2019 The Scottish Ministers make the following Regulations in exercise of the powers conferred by section 38(1) and (6)(b) and (c) and paragraphs 7(b) and 14(1) of schedule 1 of the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act 2003( a) and all other powers enabling them to do so. In accordance with paragraphs 10, 11 and 14(1) of schedule 1 of that Act they have consulted such persons as they considered appropriate, directed that notice be given of the general effect of these Regulations and considered representations and objections made. Citation and Commencement 1. These Regulations may be cited as the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019 and come into force on 1 April 2019. Amendment of the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016 2. —(1) The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016( b) are amended in accordance with paragraphs (2) to (4). (2) In regulation 3(2) (prohibition on retaining salmon), for “paragraphs (2A) and (3)” substitute “paragraph (3)”. (3) Omit regulation 3(2A). (a) 2003 asp 15. Section 38 was amended by section 29 of the Aquaculture and Fisheries (Scotland) Act 2013 (asp 7). (b) S.S.I. 2016/115 as amended by S.S.I. 2016/392 and S.S.I. 2018/37. (4) For schedule 2 (inland waters: prohibition on retaining salmon), substitute the schedule set out in the schedule of these Regulations. -

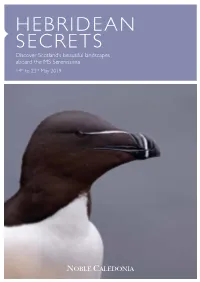

Hebridean Secrets

HEBRIDEAN SECRETS Discover Scotland’s beautiful landscapes aboard the MS Serenissima 14th to 23rd May 2019 f ever an archipelago was made for expedition cruising it is the islands off Scotland’s Iwest coast. You can travel the world visiting all manner of exotic and wonderful places, but remember that some of the finest scenery, fascinating history and most endearing people may be found close to home. Nowhere is that truer than around Scotland’s magnificent coastline, an indented landscape of enormous natural splendour with offshore islands forming stepping stones into the Atlantic. One of Europe’s true last remaining wilderness areas affords the traveller a marvellous island hopping journey through stunning scenery accompanied by spectacular sunsets and prolific wildlife. With our naturalists and local guides we will explore the length and breadth of the isles, and with our nimble Zodiac craft be able to reach some of the most remote and untouched places. There is no better way to explore this endlessly fascinating and beautiful region that will cast its spell on you than by small ship. Whether your interest lies in wildlife, gardens, photography, ancient history or simply an appreciation of this unique corner of the kingdom, this voyage has something for everyone. With no more than 95 travelling companions, the atmosphere is more akin to a private yacht trip and ashore with our local experts we will divide into small groups thereby enjoying a more comprehensive and peaceful experience. Learn something of the island’s history, see their abundant bird and marine life, but above all revel in the timeless enchantment that these islands exude to all those who appreciate the natural world.