Aalborg Universitet Irrigation Management in Nepal's Dhaulagiri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appraisal of the Karnali Employment Programme As a Regional Social Protection Scheme

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aston Publications Explorer Appraisal of the Karnali Employment Programme as a regional social protection scheme Kirit Vaidya in collaboration with Punya Prasad Regmi & Bhesh Ghimire for Ministry of Local Development, Government of Nepal & ILO Office in Nepal November 2010 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2010 First published 2010 Publications of the International Labour Offi ce enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authoriza- tion, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Offi ce, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Offi ce welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to fi nd the reproduction rights organization in your country. social protection / decent work / poverty alleviation / public works / economic and social development / Nepal 978-92-2-124017-4 (print) 978-92-2-124018-1 (web pdf) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Offi ce of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of fi rms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Offi ce, and any failure to mention a particular fi rm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

THE PROBLEMS and PROSPECTS of TOURISM in NEPAL a Thesis

THE PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS OF TOURISM IN NEPAL (A CASE STUDY OF PARBAT, DISTRICT, NEPAL) A Thesis Submitted to the Central Department of Economics, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In ECONOMICS By Sristi Karmacharya Roll No: 259/065 Reg. No: 6-2-314-13-2005 Central Department of Economics Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal September, 2013 LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION This thesis entitled “THE PROBLEM AND PROESPECT OF TOURISM IN NEPAL (A CASE STUDY OF PARBAT, DISTRICT, NEPAL)” has been prepared by Sristi Karmacharya under my supervision. I recommend this thesis for approval by the thesis committee. …………………………… Mr. Sanjay Bahadur Singh Lecturer Thesis Supervisor Date: 2070/08/24 1 APPROVAL SHEET The thesis entitled “THE PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS OF TOURISM IN NEPAL (A CASE STUDY OF PARBAT, DISTRICT, NEPAL)” submitted by Sristi Karmacharya has been accepted as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Economics. Thesis Committee ……………………………. Dr. Ram Prasad Gyanwaly Act. Head Department …………………………… Rashmi Rajkarnikar External Examiner ……………………………. Mr. Sanjay Bahadur Singh Thesis Supervisor Date: 2070/08/24 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my thesis supervisor Mr. Shanjaya Bahadur Shing, lecture of the Central Department of Economics, T.U. Kirtipur. His 2 patience, enthusiasm, co-operations and suggestions made me present this research work to produce in the present form. His brilliant, skillful supervision enriched this study higher than my expectation. I could not remain any more without giving heartfelt thanks to Mr. Sing for his painstaking supervision throughout the study period. -

Status of Wetland in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Nepal

Open Journal of Ecology, 2014, 4, 245-252 Published Online April 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/oje http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/oje.2014.45023 Status of Wetland in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Nepal Saroj Panthi1*, Maheshwar Dhakal2, Sher Singh Thagunna2, Barna Bahadur Thapa2 1Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Api Nampa Conservation Area, Darchula, Nepal 2Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal Email: *[email protected] Received 2 November 2013; revised 2 January 2014; accepted 10 January 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Wetland means the surface of the earth that is permanently or seasonally or partially covered with water. Wetlands are most productive areas for biodiversity and local livelihood support. Nepal ra- tified Ramsar convention in 1987 and started to include the wetland in Ramsar site and till now nine wetland sites are included in Ramsar site. There are still lacking systematic research and con- servation approach for these wetlands; therefore, our study attempted to assess the status of wet- lands in the Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Nepal; and explored threats and conservation chal- lenges. We prepared list of streams and lakes and collected detail information regarding area, district, block, elevation and cultural as well as ecological importance of lakes. We recorded total 11 lakes with total 304477 m2 areas. The Sundaha lake is largest lake of the reserve having signif- icant religious importance. We also recorded 7 streams in the reserve. -

Transport of Regional Pollutants Through a Remote Trans-Himalayan Valley in Nepal

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 18, 1203–1216, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-1203-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Transport of regional pollutants through a remote trans-Himalayan valley in Nepal Shradda Dhungel1, Bhogendra Kathayat2, Khadak Mahata3, and Arnico Panday1,4 1Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA22904, USA 2Nepal Wireless, Shanti Marg, Pokhara, 33700, Nepal 3Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, 14467 Potsdam, Germany 4International Center for Integrated Mountain Development, Khulmaltar, Kathmandu, 44700, Nepal Correspondence: Shradda Dhungel ([email protected]) Received: 16 September 2016 – Discussion started: 8 November 2016 Revised: 18 November 2017 – Accepted: 20 December 2017 – Published: 30 January 2018 Abstract. Anthropogenic emissions from the combustion of days to a week during non-monsoon months. Our observa- fossil fuels and biomass in Asia have increased in recent tions of increases in BC concentration and fluxes in the val- years. High concentrations of reactive trace gases and light- ley, particularly during pre-monsoon, provide evidence that absorbing and light-scattering particles from these sources trans-Himalayan valleys are important conduits for transport form persistent haze layers, also known as atmospheric of pollutants from the IGP to the higher Himalaya. brown clouds, over the Indo–Gangetic plains (IGP) from De- cember through early June. Models and satellite imagery suggest that strong wind systems within deep Himalayan valleys are major pathways by which pollutants from the 1 Introduction IGP are transported to the higher Himalaya. However, ob- servational evidence of the transport of polluted air masses Persistent atmospheric haze, often referred to as atmospheric through Himalayan valleys has been lacking to date. -

![VOICE of HIMALAYA 5 G]Kfn Kj{Tlo K|Lzif0f K|Lti7fgsf] Cfly{S Jif{ )&@÷)&# Sf] Jflif{S Ultljlw Kl/Ro Lgodfjnl, @)%( /X]Sf] 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4303/voice-of-himalaya-5-g-kfn-kj-tlo-k-lzif0f-k-lti7fgsf-cfly-s-jif-%C3%B7-sf-jflif-s-ultljlw-kl-ro-lgodfjnl-x-sf-5-604303.webp)

VOICE of HIMALAYA 5 G]Kfn Kj{Tlo K|Lzif0f K|Lti7fgsf] Cfly{S Jif{ )&@÷)&# Sf] Jflif{S Ultljlw Kl/Ro Lgodfjnl, @)%( /X]Sf] 5

ljifoqmd ;Dkfbg d08n kj{tLo kj{tf/f]x0fsf] k|d'v s]Gb| nfSkf k'm6L z] kf{ k]Daf u]Nh] z]kf{ aGb}5 k|lti7fg 5 pQdafa' e§/fO{ g]kfn kj{tLo k|lzIf0f k|lti7fgsf] cfly{s jif{ )&@÷)&# sf] jflif{s ultljlw 6 ;Dkfbs xfdLn] k|lti7fgnfO{ kj{tLo kj{tf/f]x0fsf] /fli6«o o'j/fh gof“3/ ] k|lti7fgsf] ?kdf ljsl;t ul/;s]sf 5f}+ 12 Adventure Tourism: Joj:yfks Understanding the Concept, / f] dgfy 1jfnL Recognizing the Value 16 g]kfndf :sLsf] ;Defjgf 5 eg]/ g]kfnL se/ tyf n]–cfp6 ;dfhs} ;f]r abNg' h?/L 5 43 l:k8 nfOg lk|G6;{ k|f= ln= s0ff{nLdf ko{6gsf] ljljwtf afnfh'–!^, sf7df8f} F 49 x'6' cyf{t\ /f/f 56 d'b|0f s0ff{nLsf kxf8 klg af]N5g\ 58 k"0f{ lk|lG6Ë k|]; Strategic Development nug6f]n, sf7df8f}F Plan of Nepal Mountain Academy 2016-2021 60 k|sfzs Ski Exploration Report Mustang/ g] kfn ;/ sf/ Mera Peak 93 ;+:s[lt, ko{6g tyf gful/ s p8\8og dGqfno Ski Exploration Report Khaptad 112 g]kfn kj{tLo k|lzIf0f k|lti7fg SKI COURSE - 2016 LEVEL-2 124 rfkfufpF /f]8 -;ftbf]af6f] glhs_ 6'6]kfgL, SKI COURSE - 2016 LEVEL-1 156 nlntk'/, g]kfn xfd|f lxdfn kmf]6f] lvRgsf kmf] g M ))(&&–!–%!%!(!%, %!%!()$ Website: www.man.gov.np nflu dfq} xf]Ogg\ 176 Email: [email protected] kfx'gfsf] kvf{Odf s0ff{nL 185 k|sfzsLo kj{tLo kj{tf/f]x0fsf] k|d'v s]Gb| aGb}5 k|lti7fg k|s[ltn] ;DkGg d'n's xf] g]kfn . -

Team 53: Homestay on Annapurna Circuit

HOMESTAY ON ANNAPURNA CIRCUIT Global Enterprise Experience 2013 Team 53 Marc Schoppman - New Zealand, non-native English speaker (group leader) Avuyile Andisiwe - South Africa, non-native English speaker Cao Jia Qi - Macau, non-native English speaker Dora Cecilia Balint - Hungary, non-native English speaker Gaetan Ndahimana -Rwanda, non-native English speaker Júlia Anna Balint - Hungary, non-native English speaker Julio César Arias Castaño - Colombia, non-native English speaker Sujan Adhikari - Nepal, non-native English speaker Table of Contents Executive Summary..........................................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction 1.1 Targeted Region.....................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Targeted Social and Economic Issues....................................................................................................1 2. Business Overview 2.1 The Business Model..............................................................................................................................2 2.2 Competitors in the Market.....................................................................................................................2 2.3 Marketing/Promotion.............................................................................................................................2 3. Value Creation 3.1 How Millenium Goals are Addressed....................................................................................................3 -

World Bank Document

NEPAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY Kali Gandaki ‘A’ Hydropower Plant Rehabilitation Project Environmental Assessment (EA) (Final Draft) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted to: Large Hydropower Operation and Maintenance Department Public Disclosure Authorized Nepal Electricity Authority Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: Environmental and Social Studies Department NEA Training Center, Kharipati, Bhaktapur, Nepal P.O. Box #: 21729 Kathmandu Phone No.: 977 1 66 11 580 Fax No.: 977 1 66 11 590 Public Disclosure Authorized January 28, 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. ii Abbreviations and Acronyms............................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Need for Rehabilitation Works ..................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Environmental Assessment of the Proposed Rehabilitation Project ............................................. 7 1.5 Proponent -

Cestode Parasites from Some Nepalese Mountain Shrews

[Jpn. J. Parasitol., Vol. 44, No. 3,196-209, June, 1995] Cestode Parasites from Some Nepalese Mountain Shrews ISAMU SAWADA0 AND MASASHI HARADA2) !)Biological Laboratory, Nara Sangyo University, Sango, Nara 636, Japan. 2)Laboratory of Experimental Animals, Osaka City University Medical School, Osaka 545, Japan. (Accepted May 16, 1995) Abstract Thirty-three mountain and house shrews belonging to four species of two genera taken at three collecting sites in Napal were examined for cestodes. The cestodes found were: Lineolepis soriculi sp. now., Lineolepis brevis sp. nov., Lineolepis serrata sp. nov., Ditestolepis macrostrobila sp. nov., Staphylocystis (Staphylocystis) kunisakii sp. nov., Vampirolepis nepalensis sp. nov., Vampirolepis magniovifera sp. nov., Coronacanthus parvihamata Sawada et Koyasu, 1990 and Choanotaenia sp. The cestode was observed in 67% of 33 shrews examined. Key words: Soriculus spp.; Suncus sp.; hymenolepidid cestode; Nepal. Introduction were autopsied as soon as they were captured, and their guts were fixed in Carnoy's fluid and main The cestode parasites of Nepalese shrews have tained until examination was made in Japan. The been little known except for three species recorded methods used are described in the previous paper by Sawada and Koyasu (1991 c), and Sawada, Koyasu (Sawada and Koyasu, 1990). The host specimens and Shrestha (1993), who described Pseudhymeno- were identified in accordance with Abe's descrip lepis nepalensis, Staphylocystis {Staphylocystis) tions (1971). All measurements are given in kathmanduensis and S. (S.) trisuliensis from the millimeters. house shrew, Suncus murinus. It is therefore prov able that the present paper is the first to deal with Results cestodes from the mountain shrews in Nepal, Soriculis caudatus, S. -

Karnali Report Introduction

Karnali Report Introduction Nepal is one of the mountainous country that lies in the Himalayan region and one of the climate sensitive country which is tagged as the fourth most vulnerable country of the world in the aspect of climate. Therefore the most of the areas of country has the extreme topographic as well as climatic variability. The country itself has a vast difference in the northern territory filled with huge mountains ranges to the highest in the world The Mount Everest Peak 8848 meters amsl to the southern flat planes of 70m amsl. This obviously shows the life and the cultural diversity with adverse platforms of living standards within the upper northern and lower southern parts of Nepal. Karnali is the zone of the country lying in the Mid-western development region. The area of the zone is 21351 km2 (13266.89 sq mi). The population count according to 2001 census is 309,084. Jumla is headquarter of Karnali zone. Karnali Zone is the largest zone of Nepal with the largest district Mugu, with two national parks. Shey Phoksundo National Park Shey Phoksundo (with Phoksundo Lake-- the deepest lake of Nepal), famous for the snow leopard, is Nepal's largest park with an area of 3,555 km2. Rara National Park surrounds Rara Lake -- at 10.2 km2, Nepal's largest lake known as the "Pearl of Nepal". Karnali among all the other 14 zones in the country is one of the least reachable zone where the hills and mountains are the barriers for the development of the place in the developing country like Nepal with various natural hazards, but of course the people living there have the best effort to the agriculture and animal husbandry. -

Value Chain Analysis of Choerospondias Axillaries “Lapsi” (A Case Study from Three Vdcs of Parbat District, Nepal) Research Investigator Jiwan Paudel

Value Chain Analysis of Choerospondias axillaries “Lapsi” (A case study from three VDCs of Parbat District, Nepal) Research Investigator Jiwan Paudel Tribhuvan University Institute of Forestry Pokhara A Research Project Paper submitted to Tribhuvan University, Institute of Forestry, Nepal for the partial fulfillment of Bachelor of Science in Forestry December, 2012 Value Chain Analysis of Choerospondias axillaries “Lapsi” (A case study from three VDCs of Parbat District, Nepal) Research Investigator Jiwan Paudel B.Sc. Forestry Student Institute of Forestry, Pokhara Email: [email protected] Advisor Lecturer Shrikanta Khatiwada Institute of Forestry, Pokhara Co-Advisor Associate Professor Yajna Prasad Timilsina Institute of Forestry, Pokhara A Research Project Paper submitted to Tribhuvan University, Institute of Forestry, Nepal for the partial fulfillment of Bachelor of Science in Forestry December, 2012 © Jiwan Paudel E-mail: [email protected]. Tribhuvan University Institute of Forestry, Pokhara Campus P.O.Box 43, Pokhara, Nepal Tel: +977-61-430469/431685 Fax: +977-61-430387 Website: www.iof.edu.np Citation: Paudel, J. 2012. Value Chain Analysis of Choerospondias axillaries “Lapsi”. (A case study from three VDCs of Parbat District, Nepal). B.Sc. Forestry research project paper submitted to Tribhuvan University, Institute of Forestry, Pokhara, Nepal DECLARATION I hereby declare that this project paper, “Value Chain Analysis of Choerospondias axillaries - Lapsi, A case study from three VDCs of Parbat District, Nepal” is my -

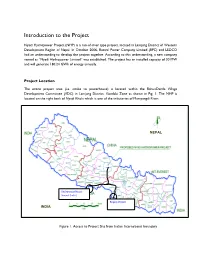

Introduction to the Project

Introduction to the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project (NHP) is a run-of-river type project, located in Lamjung District of Western Development Region of Nepal. In October 2006, Butwal Power Company Limited (BPC) and LEDCO had an understanding to develop the project together. According to this understanding, a new company named as “Nyadi Hydropower Limited” was established. The project has an installed capacity of 30 MW and will generate 180.24 GWh of energy annually. Project Location The entire project area (i.e. intake to powerhouse) is located within the BahunDanda Village Development Committee (VDC) in Lamjung District, Gandaki Zone as shown in Fig. 1. The NHP is located on the right bank of Nyadi Khola which is one of the tributaries of Marsyangdi River. NEPAL Bhairahawa (Nepal) Sunauli (India) Birganj (Nepal) INDIA Raxaul (India) Figure 1. Access to Project Site from Indian International boundary Fig. 2. Project location in Lamjung Access to Project site: The nearest road head to project site from district headquarter of Lamjung; Besisahar is located at Thakenbesi 22 km gravel road of Besisahar-Chame road. Road upto district headquarter Besisahar is blacktop. Besisahar is 185 km west from the Kathmandu and reach by the prithivi highway up to Dumre and Besisahar is 45 km from Dumre. Nearest Road head from Project Site be reached in following ways from the different parts of the Country. Technical Features of the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project is a run-of-the-river type project. The proposed system of the power plant will be run for its full capacity of 30 MW for about 5 months of the year.