School Feeding: Investment in Effective Learning – Case Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

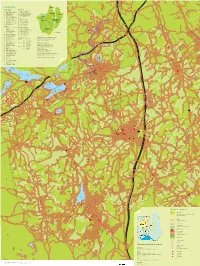

Nurmijärven Matkailu Ja Ulkoilukartta

NURMIJÄRVI NÄHTÄVYYDET RATSASTUS 1 Aleksis Kiven patsas 39 Islanninhevostalli Dynur 2 Aleksis Kiven syntymäkoti 55 Mintzun issikkatalli 3 Aleksis Kivi -huone 42 Nurmijärven Ratsastuskoulu 4 Klaukkalan kirkko 41 Perttulan Ratsastuskeskus 5 Museokahvila 44 Ratsastuskoulu Solbacka 6 Nukarin koulumuseo 53 Vuonotalli Solsikke 3 Nurmijärven Kirjastogalleria 7 Nurmijärven kirkko UINTI 2 Puupiirtäjän työhuone 45 Herusten uimapaikka 8 Pyhän Nektarioksen kirkko 46 Röykän uimapaikka 9 Rajamäen kirkko 35 Sääksjärven uimaranta 10 Taaborinvuoren museoalue 47 Tiiran uimaranta 11 Vanha hautausmaa 48 Vaaksin uimapaikka 49 Rajamäen uimahalli PALVELUT 12 Nurmijärven kunnanvirasto MAJOITUSPAIKKOJA Kirjastot 32 Holman kurssikeskus 13 Klaukkalan kirjasto 50 Hyvinvointikeskus Haukilampi 3 Nurmijärven pääkirjasto 34 Ketolan strutsitila 14 Rajamäen kirjasto 15 Hotelli Kiljavanranta 51 Lomakoti Kotoranta ELÄMYKSIÄ JA LUONTOA 54 Nukarin lomamökit 18 Alhonniitun ulkoilualue 53 Vuonotalli Solsikke 52 Ali-Ollin Alpakkatila 56 Bowling House TYÖPAIKKA-ALUEET MITEN MERKATAAN KUNTORADAT? 25 Maaniitun-Ihantolan Klaukkala A Järvihaka Kuntoratakartan värikoodit ei toimi tässä. liikuntapuisto B Pietarinmäki Numeroinnilla pelkästään?... 30 Frisbeegolfrata C Ristipakka Rajamäen liikuntapuisto Nurmijärvi D Alhonniittu 19 Isokallion ulkoilualue E Ilvesvuori Rajamäki – Kehityksen maja 20 Klaukkalan jäähalli F Karhunkorpi Kehityksen Majan kilpalatu 21 Klaukkalan urheilualue G Kuusimäki Märkiön lenkki (Kehityksen majalta) 22 Tarinakoru Rajamäki H Ketunpesä Matkun lenkki (Kehityksen -

Space to Live and to Grow in the Helsinki Region Welcome to Nurmijärvi

In English Space to live and to grow in the Helsinki region Welcome to Nurmijärvi Hämeenlinna 40 min Choose the kind of environment that you prefer to live in: an urban area close Tampere 1 h 20 min to services, or a rural environment close to nature. Hanko 2 h 10 min Kehä III Nurmijärvi centre Enjoy the recreational facilities on offer: there are cultural and other events – (Outer ring road) 12 min also for tourists, and there are possibilities to exercise and enjoy nature almost Hyvinkää 20 min outside your own front door. Services from the Helsinki Metropolitan Area add to Helsinki 30 min the offering. Estimated times from the E12 junction near the centre of Nurmijärvi Benefit from a wide range of services that take into account your life situation: from early childhood to basic education and further training, and later on, elderly General facts Main population people are offered a high standard of care. • Surface area: 367 km2 centres • Inhabitants: over 40 000 • Klaukkala: 40 % Your business will be ideally located, making logistics easy to arrange: a short • Under 15-yearsElinvoimaa old: 25 % ja• Nurmijärvielämisen centre: 20 % distance from the ports and airport, you’ll benefit from good road communications tilaa Helsingin• Rajamäki: seudulla 18 % in both east-west and north-south directions, while being away from the rush. Choose your workplace and your journey to work: apart from your own munici- HYVINKÄÄ pality, the Helsinki Metropolitan Area and the municipalities to the north are near Lahteen neighbours. Tampereelle MÄNTSÄLÄ 25 POR- Klaukkala Rajamäki NAI- Nurmijärvi offers all this – a large enough municipality to be able to provide the nec- JÄRVENPÄÄ NEN essary services and infrastructure for modern life, as well as to grow and develop E 12 Kirkonkylä continuously, but still small enough to provide a living space at a competitive cost. -

Print Entire Issue (PDF)

The National Library of Finland Bulletin 2009 http://www.kansalliskirjasto.fi/extra/bulletin/ THE NATIONAL LIBRARY of Finland Bulletin 2009 Minna Karvonen EDITORIAL The National Digital Library The National Digital Library is now making the information resources of libraries, archives and museums available, and preserving them for future users. Increased immaterial exchange and a profound change in the way information is produced and disseminated characterize the information and competence society. The mission of libraries, archives and museums as possessors, intermediaries and repositories of essential electronic information resources is of vital importance for such a society. National information society policy definitions emphasize the development of common infrastructures and services that promote the utilization of mainly publicly funded electronic information resources as efficiently as possible. The National Digital Library project Said about the National Library: managed by the Ministry of Education "In these times of unbridled (www.kdk2011.fi) is part of the development materialism, a place where one can still of national electronic infrastructures and find wisdom and spirituality, as well as customer-oriented electronic service entities. respite from the relentless pursuit of It is one of the public administration projects one's objectives, is more valuable than defined in the Ubiquitous Information Society Action Plan implementing the Government Resolution gold." on the Objectives of the National Information Society Policy 2007-2011. -

Kivenkyyti - Ajaisihan Sillä Myös Aleksis

Nurmijärven palveluliikenteen aikataulut Kivenkyyti - ajaisihan sillä myös Aleksis. 3.6.2013 alkaen Sisällysluettelo Matkan hinta ja maksaminen .........................4 Lipputuotteet ......................5 Palveluliikennereitit 2 Kirkonkylä ......................................................................6 3 Järvikierros ....................................................................7 5 Karhunkorpi-Nukari-Suomies ................................8 6 Palojoki-Raala............................................................... 9 7 Siippoo-Palojoki kotikauppakyyti ......................10 10 Klaukkala .....................................................................11 12 Lepsämän kotikauppakyyti ..................................12 16 Valkjärven koulu-Klaukkala ...................................13 20 Rajamäki ......................................................................14 27 Kirkonkylä-Rajamäki ................................................15 Liityntälinjat 34 Lepsämän ja Rinnekodin kesäliikenne ..............16 35/39/492 Klaukkala-Kirkonkylä-Klaukkala .............17 37 Rajamäki-Röykkä-Kirkonkylä ...............................18 46 Isokallion liityntä ......................................................19 Kartat: © Nurmijärven kunta, Kiinteistö- ja mittaustoimi Tilauspuhelin 09 - 274 6900 2 pvm/mpm Tervetuloa Kivenkyytiin, palveluliikenteen bussiin. Kivenkyyti palvelee kaikkia Nurmijärvellä liikkuvia. Matalalattia-autojen ansiosta Kivenkyyti sopii hyvin myös vanhuksille, liikuntaesteisille ja lastenvaunujen -

Kuninkaantie2019 Kartta

S A L K Ä 8 E Ypäjänkylä 140 L P 7 U S S Pulsa Simola Putsaari Karjalankylä l.puisto Otsola 284 Susikas Hyvikkälä Janakkalan kk. Herrala A 21 A L P A Luumäen kk. 28 Kalanti Uusikartano Oripää JOKIOINEN 13 Oinaala Hietoinen 5 Pasina U S Hiisiö Kuusaa S Tani 11 10 28 16 S E Ranta-Utti Salmi Nästi Loimaa 17 L 6 33 Raippo 388 Uusikaupunki Teuro 20 Tanttala Löyttymäki Pennala K Ä 1 Somerharju Rikkilä 62 Tillola 15 Kaitjärvi Lahti 54 23 Heinämaa Kymintehdas Heimala Suo-Anttila YPÄJÄ Forssa Kaukjärvi Nummenkylä 3 Jokimaa 62 Luhtikylä 4 28 Kausala Kaipiainen Nystad 8 34 Myllykylä 283 Järvelä 12 Rannanmäki 41 Kauhanoja 19 29 13 196 Karjalan kk. Kalela 89 10 213 Ypäjä Minkiö Leppäkoski Kuivanto 9 Utti Saaramaa 25 Vainikkala Pihlava KÄRKÖLÄ Keituri Virenoja Perheniemi Luotola Sairinen 16 290 Haminankylä 54 9 360 Enäjärvi Kaloinen Isokari Vehmalainen 85 Mellilä Vaulammi 24 Ahoinen Lappila E75 14 24 Koskunen Koria 25 Suoknuuti Nutikka 14 92 204 Tammela 13 Kouvola Mättö 1 9 11 17 10 13 24 14 1 Lietsa Tervakoski Turkhauta 5 20 21 16 Enskär Varanpää Kivikylä MYNÄMÄKI Kurjenrahkan 19 Pöytyän kk. 11 22 5 Lohja – Järvikaupunki Järvikylä ORIMATTILA Sääskjärvi 23 22 Mattinen Nikinoja 4 kans.puisto Ryttylä Mommila 19 46 Savero 375 Hyttilä E8 16 24 22 Jokioinen Vojakkala 130 7 Marttila Orimattila 16 Rautakorpi 92 Patolahti 11 14 TAMMELA 23 Huhdanoja 19 Haapa-Kimola Värälä Villala Vehmaan kk. Takkulankulma Kuusjoki Lohja on elämyksellinen järvikaupunki, keskellä11 vehmasta uusmaalaista luontoa, vain puo- 20 Ylämaa 9 Vehmaa PÖYTYÄ 295 4ZLQR Isoperä Porras 20 Oitti 172 Niinikoski Hietana Haapala 194 Korvensuu Riihivalkama 14 8 Vähikkälä 11 164 23 18 Takamaa 359 KOUVOLA Tarvainen Riihikoski Topeno len tunnin ajomatkan päässä Helsingistä. -

Nurmijärven JOUKKOLIIKENTEEN AIKATAULUT

Nurmijärven JOUKKOLIIKENTEEN AIKATAULUT 7.1. – 31.5.2020 Liikennöintikauden vaihtumisessa on vaihtelua liikennöitsijöittäin. Tarkista aikataulut tarvittaessa liikennöitsijältä tai Matkahuollosta. Koosteen on tuottanut: NURMIJÄRVEN KUNTA Kunta ei vastaa aikataulukirjan sisällöstä. MATKUSTAJALLE Tähän Nurmijärven kunnan julkaisemaan koosteeseen on kerätty aikataulut tärkeimmistä asukkaita palvelevista joukkoliikenneyhteyksistä ajalle 7.1.–31.5.2020. Liikennöintikauden vaihtumisessa voi olla liikennöitsijäkohtaisia eroja. Aikataulujulkaisu ei sisällä Nurmijärven kunnan palvelulinjojen reitti- tai aikataulutietoja. Aikataulujulkaisu on tehty liikennöitsijöiden ilmoittamien muutostietojen avulla. Nurmijärven kunta ottaa mielellään vastaan tietoja puutteista tai virheistä sekä aikataulun kehitysideoita. Joukkoliikenteen aikataulut ja muuta tietoa mm. lipputuotteista on tarjolla Uudenmaan joukkoliikenteen infosivuilla www.uudenmaanjoukkoliikenne.fi. Liikennöitsijöiden Internet-sivuilta löydät tuoreimmat aikataulutiedot ja tiedot mahdollisista muutoksista. Lisäksi joukkoliikennetietoa löytyy kuntien sivuilta: www.jarvenpaa.fi www.pornainen.fi www.nurmijarvi.fi www.mantsala.fi www.tuusula.fi www.hyvinkaa.fi Tässä aikataulukoosteessa esitettyjen linjojen lisäksi Nurmijärven yhteyksiä palvelevat Keski-Uudenmaan ja pääkaupunkiseudun väliset linjat. Katso aikataulujulkaisu ”Keski-Uudenmaan ja pääkaupunkiseudun välinen bussiliikenne”. NURMIJÄRVEN KUNNAN YHTEYSHENKILÖ: Riku Hellgren, [email protected], puh. 040 317 2357 LIIKENNÖITSIJÖIDEN -

Tectonic Evolution of the Svecofennian Crust in Southern Finland

Tectonic evolution of the Svecofennian crust in southern Finland – a basis for characterizing bedrock technical properties Edited by Matti Pajunen Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper 47, 15–160, 2008. TECTONIC EVOLUTION OF THE SVECOFENNIAN CRUST IN SOUTHERN FINLAND by Matti Pajunen*, Meri-Liisa Airo, Tuija Elminen, Irmeli Mänttäri, Reijo Niemelä, Markus Vaarma, Pekka Wasenius and Marit Wennerström Pajunen, M., Airo, M.-L., Elminen, T., Mänttäri, I., Niemelä, R., Vaarma, M., Wasenius, P. & Wennerström, M. 2008. Tectonic evolution of the Svecofennian crust in southern Finland. Geological Survey of Finland, Special Paper 47, 15–160 , 53 figures, 1 table and 9 appendices. The present-day constitution of the c. 1.9–1.8 Ga old Svecofennian crust in south- ern Finland shows the result of a complex collision of arc terranes against the Ar- chaean continent. The purpose of this study is to describe structural, metamorphic and magmatic succession in the southernmost part of the Svecofennian domain in Finland, in the Helsinki area. Correlations are also carried out with the Pori reference area in southwestern Finland. A new tectonic model on the evolution of the southern Svecofennian domain is presented. The interpretation is based on field analyses of structural successions and magmatic and metamorphic events, and on interpretation of the kinematics of the structures. The structural successions are linked to new TIMS and SIMS analyses performed on eight samples and to published age data. The Svecofennian structural succession in the study area is divided into deforma- tion phases DA-DI; the post-Svecofennian events are combined as a DP phase. Kinemat- ics in the progressively-deforming transtensional or transpressional belts complicates analysis of the overprinting relations due to their simultaneous contractional and exten- sional structures. -

Author's Response

1 Dear Editor Seibert, 2 3 We would like to thank You and the reviewer for comments. Detailed comments addressing all 4 questions/comments/suggestions of the reviewer #2 are listed below. We have also made additional 5 changes to the manuscript, these changes with justifications are listed below the reviewer #2 6 comments. We hope that these additional changes improve the manuscript. We have added the 7 tracked manuscript below the all corrections. The page and line numbers given below are correct in 8 tracked version. 9 Sincerely 10 Anne Rautio 11 12 Non-public comments to the Author: 13 p3l23, were instead of was 14 Done 15 p4l11, delete the before TIR 16 Done 17 p5l21, add the before field study sites 18 Done 19 p8l13 was->were, what does T_minr refer to here? reformulate? 20 We still prefer the “was” and have left this as previous form. Tminr refers to explanation why Tminr was 21 selected instead of image sampling or weighted averages. We have reformulated the sentence as 22 followingly. 23 Tminr was selected for this study instead of the extraction methods based on image sampling or 24 weighted averages used in previous studies (Torgersen et al., 2001 Cristea and Burges, 2009) to more 25 efficiently localize the anomalously cold temperatures in the main stream channel indicating GW 26 contributions into the river flow. 27 p9,l18, add the explanation of DSi here again, your reader will appreciate this 28 We have added the dissolved silica in the sentence. 29 p13l20, please use the normal notation for ƍPearson (I suggest, r_Pearson _indicating subscript 30 We have used the rPearson. -

Historiallisen Ajan Muinaisjäännösten Inventointi 5.5

Nurmijärvi Historiallisen ajan muinaisjäännösten inventointi 5.5. – 23.5.2008 Tapani Rostedt Museovirasto Rakennushistorian osasto 2 Arkisto- ja rekisteritiedot Kunta: Nurmijärvi Tutkimuksen laatu:inventointi Kohteiden ajoitus: historiallinen Peruskartat: 2041 07, 2041 11, 2041 12, 2042 10, 2043 03, 2043 06, 2044 01, 2044 04 Projekti: Nurmijärvi, historiallisen ajan muinaisjäännösten inventointi Tutkimuslaitos: Museovirasto, rakennushistorian osasto (MV/RHO) Tutkija: FM Tapani Rostedt Kenttätyöaika: 5.5. – 23.5.2008 Tutkimuskustannukset: 11 200 € Tutkimusten kustantaja: Nurmijärven kunta Löydöt: - Diapositiivit: - Mustavalkonegatiivit: 125 937:1–125 Digikuvat: 125 939:1–139 Inventointiraportin sivumäärä: 142 s. Liitteet: Muinaisjäännösten kohdeluettelo, muinaisjäännöksiin liittyvät gps- pisteet, mustavalkonegatiivien luettelo, digikuvien luettelo, karttaluettelo, kartat Alkuperäisen kaivauskertomuksen säilytyspaikka: Museovirasto, rakennushistorian osaston arkisto, Helsinki 3 Sisällysluettelo Arkisto- ja rekisteritiedot......................................................................................... 2 Sisällysluettelo....................................................................................................... 3 Tiivistelmä.............................................................................................................. 6 1. Johdanto............................................................................................................ 7 2. Ympäristö.......................................................................................................... -

Vantaanjoki Virtaus Sallii Melomisen Molempiin Suuntiin, Alueita, Ja Lupien Myyntipaikat Löydät Esitteen Yhdistää Etelä-Hämeen Suomenlahteen

10. painos, 2018 10. painos, Tervetuloa Vantaanjoelle! alkusyksyllä joen virtaama on usein vain ajan kalastuksen mahdollisuudet ovat parantu- muutama kuutiometri sekunnissa. Vähäinen neet. Vesistöalueella on useita kalastuslupa- Sadan kilometrin pituinen Vantaanjoki virtaus sallii melomisen molempiin suuntiin, alueita, ja lupien myyntipaikat löydät esitteen yhdistää Etelä-Hämeen Suomenlahteen. mutta toisaalta se hidastaa kulkua koskissa kääntöpuolelta. Useaan kalastuskohteeseen Vesireittiä ovat käyttäneet niin kivikauden ja virtapaikoissa. Virtaamahuippujen aikaan istutetaan kirjolohta. Vantaanjoki luokitellaan eränkävijät kuin hämäläiset kauppamatkoil- alkukeväällä ja loppusyksyllä virtaama vaelluskalavesistöksi, jossa tarvitsee aina laan. Virran voimaa valjastettiin pyörittä- alajuoksulla saattaa olla jopa 300 m3/s. vesialueen omistajan luvan kalastaessa koski- ja mään myllyjä ja sahoja. Asutus ja teollisuus Vantaanjoen suurimmat kosket ovat virta-alueilla. Muualla on eräitä poikkeuksia kuormittivat voimakkaasti vesistöä. Viime koskimelojien suosiossa tulva-aikoina. lukuun ottamatta sallittu onkia ja pilkkiä vuosikymmeninä vesiensuojelu on tehostu- Melontareitin varrella, välillä Hyvinkään jokamiehenoikeudella sekä viehekalastaa nut ja veden laatu on parantunut huomatta- Vaiveronkosket – Nurmijärven Myllykoski – kalastonhoitomaksulla. vasti. Lukuisia koskia ja uomia on kunnostet- Helsingin Ruutinkoski – Vanhankaupungin- Vantaanjoen rannoilla on runsaasti tu. Nyt Vantaanjoki tarjoaa monipuolisen koski, on ohitus- ja rantautumispaikoissa -

(Eds.) Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference

H. Li, R. Suomi, Á. Pálsdóttir, R. Trill, H. Ahmadinia (Eds.) Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Well-Being in the Information Society: Fighting Inequalities (WIS 2018) Turku Centre for Computer Science TUCS Lecture Notes No 28, August 2018 Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Well-Being in the Information Society: Fighting Inequalities (WIS 2018) Hongxiu Li, Reima Suomi, Ágústa Pálsdóttir, Roland Trill, and Hamed Ahmadinia (Eds.) 27 – 29 August, 2018 Turku, Finland Editors Hongxiu Li Tampere University of Technology Finland Reima Suomi University of Turku Finland Ágústa Pálsdóttir University of Iceland Iceland Roland Trill Fachhochschule Flensburg Germany Hamed Ahmadinia Åbo Akademi University Finland ISBN 978-952-12-3727-0 ISSN 1797-8831 PREFACE This publication contains selected and reviewed abstracts that were presentded at the Well- Being In the Information Society - WIS 2018 conference, which took place in Turku in Finland, during 27-29 August, 2018. The conference, which started in 2006, is a biannual event that is now being held for the seventh time. The conference is multidisciplinary in nature. It brings together scientist and practitioners from several academic disciplines and professional specializations from around the world who share their current expertise and experiences, and exchange their views on the latest developments within the field. The focal point of the WIS conference has from the beginning been the use of information technology to promote equality in well-being. This, together with the main theme of the conference this year, ‘fighting inequalities’, is reflected in the content and emphasis in the publication. We would like to express our gratitude to all of those who have contributed to the WIS 2018 conference. -

Nurmijärven Liikenneturvallisuus- Suunnitelma

UUDENMAAN ELINKEINO-, LIIKENNE- JA YMPÄRISTÖKESKUKSEN JULKAISUJA x | 2010 Nurmijärven liikenneturvallisuus‐ suunnitelma Mahdollinen alaotsikko Tekijän nimi Mahdollisen toisen tekijän nimi Helsinki 2010 Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskus Uudenmaan elinkeino‐,liikenne‐ ja ympäristökeskuksen julkaisuja X | 200X 1 (Huom. tämän sekä kansilehden alareunassa on "näkymätön" laatikko, joka peittää alatunnisteen. Älä poista niitä!) UUDENMAAN ELINKEINO-, LIIKENNE- JA YMPÄRISTÖKESKUKSEN JULKAISUJA X | 2010 Uudenmaan elinkeino-, liikenne- ja ympäristökeskus Kannen taitto: xxxxxxxxxxx Kannen kuva: xxxxxxxxx Paino, paikkakunta, 2010 (tämä rivi pois, jos julkaisu on vain sähköisessä muodossa) Julkaisu on saatavana myös internetistä: http://www.ely-keskus.fi/uusimaa/julkaisut ISSN xxxxxxxxxx (painettu) (tämä rivi pois, jos julkaisu on vain sähköisessä muodossa) ISBN xxxxxxxxxx (painettu) (tämä rivi pois, jos julkaisu on vain sähköisessä muodossa) ISSN xxxxxxxxxx (verkkojulkaisu) ISBN xxxxxxxxxx (verkkojulkaisu) 2 Uudenmaan elinkeino‐, liikenne ja ympäristökeskuksen raportteja X | 200X SISÄLLYS 1 Lähtökohdat ..................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Taustaa ................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Suunnittelualue ................................................................................................. 6 1.2.1 Liikenneverkko ..........................................................................................