Solway Moss 1542

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scottish Banner

thethethe ScottishScottishScottish Banner BannerBanner 44 Years Strong - 1976-2020 www.scottishbanner.com A’ Bhratach Albannach Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 VolumeVolumeVolume 44 36 Number36 Number Number 6 11 The 11 The world’sThe world’s world’s largest largest largest international international international Scottish Scottish Scottish newspaper newspaper newspaper December May May 2013 2013 2020 Celebrating US Barcodes Hebridean history 7 25286 844598 0 1 The long lost knitting tradition » Pg 13 7 25286 844598 0 9 US Barcodes 7 25286 844598 0 3 7 25286 844598 0 1 7 25286 844598 1 1 The 7 25286 844598 0 9 Stone of 7 25286 844598 1 2 Destiny An infamous Christmas 7 25286 844598 0 3 repatriation » Pg 12 7 25286 844598 1 1 Sir Walter’s Remembering Sir Sean Connery ............................... » Pg 3 Remembering Paisley’s Dryburgh ‘Black Hogmanay’ ...................... » Pg 5 What was Christmas like » Pg 17 7 25286 844598 1 2 for Mary Queen of Scots?..... » Pg 23 THE SCOTTISH BANNER Volume 44 - Number 6 Scottishthe Banner The Banner Says… Volume 36 Number 11 The world’s largest international Scottish newspaper May 2013 Publisher Contact: Scottish Banner Pty Ltd. The Scottish Banner Editor PO Box 6202 For Auld Lang Syne Sean Cairney Marrickville South, NSW, 2204 forced to cancel their trips. I too was 1929 in Paisley. Sadly, a smoking EDITORIAL STAFF Tel:(02) 9559-6348 meant to be over this year and know film canister caused a panic during Jim Stoddart [email protected] so many had planned to visit family, a packed matinee screening of a The National Piping Centre friends, attend events and simply children’s film where more than David McVey take in the country we all love so 600 kids were present. -

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans 1 2 Contents Page 2 Chairman’s Introduction Page 3 Arthuret Community Plan Introduction Page 4 Kirkandrews-on-Esk Plan Introduction Page 5 Arthuret Parish background and History Page 7 Brief outline of Kirkandrews on Esk Parish and History Page 9 Arthuret Parish Process Page 12 Kirkandrews on Esk Parish Process Page 18 The Action Plan 3 Chairman’s Introduction Welcome to the Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan – a joint Community Action Plan for the parishes of Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk. The aim is to encourage local people to become involved in ensuring that what matters to them – their ideas and priorities – are identified and can be acted upon. The Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan is based upon finding out what you value in your community. Then, based upon the process of consultation, debate and dialogue, producing an Action Plan to achieve the aspirations of local people for the community you live and work in. The consultation process took several forms including open days, questionnaires, workshops, focus group meetings, even a business speed dating event. The process was interesting, lively and passionate, but extremely important and valuable in determining the vision that you have for your community. The information gathered was then collated and produced in the following Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan. The Action Plan aims to show a balanced view point by addressing the issues that you want to be resolved and celebrating the successes we have achieved. It contains a range of priorities from those which are aspirational to those that can be delivered with a few practical steps which will improve life in our community. -

Kirkandrews on Esk: Introduction1

Victoria County History of Cumbria Project: Work in Progress Interim Draft [Note: This is an incomplete, interim draft and should not be cited without first consulting the VCH Cumbria project: for contact details, see http://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/] Parish/township: KIRKANDREWS ON ESK Author: Fay V. Winkworth Date of draft: January 2013 KIRKANDREWS ON ESK: INTRODUCTION1 1. Description and location Kirkandrews on Esk is a large rural, sparsely populated parish in the north west of Cumbria bordering on Scotland. It extends nearly 10 miles in a north-east direction from the Solway Firth, with an average breadth of 3 miles. It comprised 10,891 acres (4,407 ha) in 1864 2 and 11,124 acres (4,502 ha) in 1938. 3 Originally part of the barony of Liddel, its history is closely linked with the neighbouring parish of Arthuret. The nearest town is Longtown (just across the River Esk in Arthuret parish). Kirkandrews on Esk, named after the church of St. Andrews 4, lies about 11 miles north of Carlisle. This parish is separated from Scotland by the rivers Sark and Liddel as well as the Scotsdike, a mound of earth erected in 1552 to divide the English Debatable lands from the Scottish. It is bounded on the south and east by Arthuret and Rockcliffe parishes and on the north east by Nicholforest, formerly a chapelry within Kirkandrews which became a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1744. The border with Arthuret is marked by the River Esk and the Carwinley burn. 1 The author thanks the following for their assistance during the preparation of this article: Ian Winkworth, Richard Brockington, William Bundred, Chairman of Kirkandrews Parish Council, Gillian Massiah, publicity officer Kirkandrews on Esk church, Ivor Gray and local residents of Kirkandrews on Esk, David Grisenthwaite for his detailed information on buses in this parish; David Bowcock, Tom Robson and the staff of Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle; Stephen White at Carlisle Central Library. -

Early Christian' Archaeology of Cumbria

Durham E-Theses A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. How to cite: O'Sullivan, Deirdre M. (1980) A reassessment of the early Christian' archaeology of Cumbria, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7869/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Deirdre M. O'Sullivan A reassessment of the Early Christian.' Archaeology of Cumbria ABSTRACT This thesis consists of a survey of events and materia culture in Cumbria for the period-between the withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain circa AD ^10, and the Viking settlement in Cumbria in the tenth century. An attempt has been made to view the archaeological data within the broad framework provided by environmental, historical and onomastic studies. Chapters 1-3 assess the current state of knowledge in these fields in Cumbria, and provide an introduction to the archaeological evidence, presented and discussed in Chapters ^--8, and set out in Appendices 5-10. -

Eden and Lyne Buzz June and July 2017

Eden and Lyne Buzz Eden and Lyne Buzz June and July 2017 FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF ROCKCLIFFE, CARGO, HARKER, BLACKFORD,WESTLINTON AND ALL POINTS IN BETWEEN BRITISH PIE NIGHT EVERY WEDNESDAY FROM 5pm 3 PIES AVAILABLE £7 PER MEAL SOLAR OR NUCLEAR—IS THAT THE QUESTION?” 24 Eden and Lyne Buzz Eden and Lyne Buzz “Detectives” is the whole-school topic this IN THIS EDITION LIST OF ADVERTISED SERVICES Cover Photo— Stormy Dawn at Blackrigg Accountant—Page 16 term’; the children are investigating many Page 2 - Constitution, Advertisers, Copy Date Boiler Servicing, Repairs and Installation—Page 19 different areas. The infants have been on a Page 3— Editorial, What’s On Building Society/Bank—Page 22 minibeast hunt around the school grounds Page 4— Blackford WI and PCC Catering—Page 14 and then researched facts about their Page 5—The Carlisle Patriot 1815 and the Litterpick Chimney Sweeps—Pages 8 and 15 finds. They have also made moving models of snails and LYNEFOOT KENNELS Page 7— Children’s Page Chiropodist—Page 10 caterpillars whilst practicing their cutting and sticking skills. http://lynefootkennelsltd.co.uk Page 9 — The High Tides of 1967 Coffee Mornings—Page 6 At playtimes, there are many minibeast homes being cre- Page 11– Presentation of a BEM Computer repairs etc—10 ated on the school field from all kinds of materials. Established in 2009 Lynefoot Kennels is a family run Page 12— Rockcliffe Parish Council Domestic Appliances Repairs and Sales—11 The junior children are being history detectives and are business. With help from a small, dedicated team, Page 13 — Kingmoor PC and Westlinton PC Electrical Repairs etc— Page 6 investigating the impact that the Romans had on the local we want you to leave your dog knowing that they Page 14— Westlinton AGM Report Firewood/Logs—Page 16 area. -

PREMISES with DPS AS of 18 February 2019 12:56 Club

PREMISES with DPS AS OF 18 February 2019 12:56 Club Premises Certificate With Alcohol DPS Licence Details CP002 Commences 24/11/2005 Premise Details Longtown Social Club - 12 -14 Swan Street Longtown Cumbria CA6 5UY Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder LONGTOWN SOCIAL CLUB DPS Licence Details CP003 Commences 24/11/2005 Premise Details Denton Holme Working Mens Conservative Club Limited - 1 Morley Street Denton Holme Carlisle Cumbria Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder DENTON HOLME WORKING MENS CONSERVATIVE CLUB LTD DPS Licence Details CP005 Commences 24/11/2005 Premise Details Courtfield Bowling Club - River Street Carlisle Cumbria Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder COURTFIELD BOWLING CLUB DPS Licence Details CP007 Commences 20/12/2017 Premise Details Dalston Bowling Club - The Recreation Field Dalston Cumbria CA5 7NL Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder DALSTON BOWLING CLUB COMMITTEE DPS Licence Details CP008 Commences 28/03/2006 Premise Details Cummersdale Village Hall - Cummersdale Carlisle Cumbria CA2 6BH Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder EMBASSY CLUB DPS Licence Details CP009 Commences 04/03/2010 Premise Details Linton Bowling Club - Sandy Lane Great Corby Carlisle Cumbria CA4 8NQ Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder THE COMMITTEE LINTON BOWLING C DPS Licence Details CP010 Commences 24/11/2011 Premise Details Carlisle Subscription Bowling Club - Myddleton Street Carlisle Cumbria CA1 2AA Expires 31/12/9999 Telephone licence Holder CARLISLE SUBSCRIPTION BOWLING DPS Licence Details CP011 -

Now the War Is Over

Pollard, T. and Banks, I. (2010) Now the wars are over: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields. International Journal of Historical Archaeology,14 (3). pp. 414-441. ISSN 1092-7697. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/45069/ Deposited on: 17 November 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Now the Wars are Over: the past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Tony Pollard and Iain Banks1 Suggested running head: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Centre for Battlefield Archaeology University of Glasgow The Gregory Building Lilybank Gardens Glasgow G12 8QQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)141 330 5541 Fax: +44 (0)141 330 3863 Email: [email protected] 1 Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland 1 Abstract Battlefield archaeology has provided a new way of appreciating historic battlefields. This paper provides a summary of the long history of warfare and conflict in Scotland which has given rise to a large number of battlefield sites. Recent moves to highlight the archaeological importance of these sites, in the form of Historic Scotland’s Battlefields Inventory are discussed, along with some of the problems associated with the preservation and management of these important cultural sites. 2 Keywords Battlefields; Conflict Archaeology; Management 3 Introduction Battlefield archaeology is a relatively recent development within the field of historical archaeology, which, in the UK at least, has itself not long been established within the archaeological mainstream. Within the present context it is noteworthy that Scotland has played an important role in this process, with the first international conference devoted to battlefield archaeology taking place at the University of Glasgow in 2000 (Freeman and Pollard, 2001). -

HENRY VIII TRAIL the Story of Henry’S Visit with His Allegedly Adulterous Queen, Catherine Howard in 1541

HENRY VIII TRAIL The story of Henry’s visit with his allegedly adulterous Queen, Catherine Howard in 1541. The King sat nearly 2 weeks, ulcerous, syphilitic and constipated, fuming and waiting for his nephew James V of Scotland to attend a peace conference that never happened. Lavish preparations were made for the King’s reception by a City Council so terrified of the King after the Pilgrimage of Grace that they grovelled in the mud to meet him. Henry also closed down all the Monasteries and hospitals in York, even the public lavatories, because of alleged hanky-panky by the monks and nuns. St Leonards Hospital This was founded by King Athelstan in 935 AD as the Hospital of St Peter’s and may go back even further. It was refounded as the Hospital of St Leonard by King Stephen after the great fire of York in 1137. At its height the Hospital stretched almost the Minster-the Theatre Royal is built on its Undercrofts and the Red House incorporates part of its gatehouse. The Time Team Excavation of 1999 and At its height it had over 200 people in its care ranging from the poor to those who chose to retire there to live out their days. It had 13 Augustinian Canons, 8 Nuns plus Lay Brothers and servants making perhaps 300 people in all. It was surrendered to the Crown in 1539 and all had to leave. It was the last of the great religious house in York to close on 1st Dec 1540. The last Master, Thomas Magnus, got a manor at Beningbrough Grange. -

1 Print Culture, State Formation and an Anglo-Scottish Public, 1640-1648

Print culture, state formation and an Anglo-Scottish public, 1640-1648 Jason Peacey The civil war newsbook the Scotish Dove – which appeared weekly from the London press of Laurence Chapman between October 1643 and the end of 1646 – has recently been described as the voice of the Scottish interest, and even as the “first Scottish newspaper.” It is said to have prompted “a consistently and resolutely Scottish perspective,” and one of its prime aims is said to have been to “describe, defend, celebrate and when necessary apologise for” the Scots and the army of the covenant. Commentators agree that this involved “cloying piety” and “unpleasantness,” and that its author was “a blue nose, a Puritan in the worst sense of the word,” even if they might not all go as far as to suggest that it was the mouthpiece for the Scottish commissioners in London, or that it represented “effective public relations” for the Scottish political and religious agenda.1 It has proved tempting, in other words, to see the Dove as part of a wider story which centres upon the Scots as aggressive appropriators and exploiters of print culture, and as being peculiarly interested in, and capable of, using texts to reach out to different groups in different countries. According to this version of the “print revolution,” the “explosion” of print that occurred in the mid-seventeenth century involved “a forest fire, started in Edinburgh,” and one of “the most systematic and concerted campaigns hitherto attempted by a foreign power to bombard a separate kingdom with propaganda, thereby using the printed word to manipulate political opinion and fundamentally to alter the 1 A. -

Eden and Lyne Buzz Eden and Lyne Buzz APRIL and MAY 2018

Eden and Lyne Buzz Eden and Lyne Buzz APRIL AND MAY 2018 THE EDEN AND LYNE BUZZ ANNUAL ACCOUNTS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF ROCKCLIFFE, CARGO, HARKER, Our thanks to Mrs Janette Fisher who has maintained our accounts on a voluntary basis throughout the first year. Shown BLACKFORD,WESTLINTON AND ALL POINTS IN BETWEEN below are the figures of income, expenditure and balances for the first year’s issues of the Eden and Lyne Buzz. DONATIONS - £650 in April was donated by a number of benefactors who wanted a Community Magazine to be £5 per year (6 Issues) Or £1-50 resurrected. £450 in July was donated by the Cumberland Building Society Community Fund to sponsor the printing of the Aug/Sep issue and £500 in August came from the Westlinton Parish Council’s grant from the Burn Beck Windfarm Fund. SUBSCRIPTIONS - £1775 equals subscriptions paid and small amounts donated by individual subscribers. Over 300 subscriptions have actually been paid but some copies have been distributed on a complimentary basis. ADVERTISING – Self explanatory. EXPENDITURE – The first 2 issues were printed by local charity in Carlisle (£486 and £479); when their services were no longer available, tenders were sent out and “Print Out” provided the best quote and got the job for 6 issues at approx. £290 per edition. Extra printing was paid for in February 2018, £150 was a remuneration to the person who does most of the layout of the magazine and £23.45 was spent on plastic stands for sales of the magazine at varous outlets. The Trustees recommend that the £650 start up donations and the £500 from the Beck Burn Grant are retained within the accounts and that £800 be given to local good causes, organisations or charities nominated by the readership in accordance with the Constitution. -

13 Annex to Appendix B

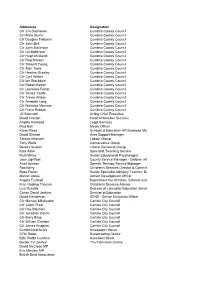

Addressee Designation Cllr Jim Buchanan Cumbria County Council Clrl Anne Burns Cumbria County Council Cllr Douglas Fairbairn Cumbria County Council Cllr John Bell Cumbria County Council Cllr John Mallinson Cumbria County Council Cllr Liz Mallinson Cumbria County Council Cllr Hugh McDevitt Cumbria County Council Cllr Reg Watson Cumbria County Council Cllr Stewart Young Cumbria County Council Cllr Alan Toole Cumbria County Council Cllr Heather Bradley Cumbria County Council Cllr Cyril Weber Cumbria County Council Cllr Ian Stockdale Cumbria County Council Cllr Robert Betton Cumbria County Council Clr Lawrence Fisher Cumbria County Council Cllr James Tootle Cumbria County Council Cllr Trevor Allison Cumbria County Council Cllr Amanda Long Cumbria County Council Cllr Nicholas Marriner Cumbria County Council Cllr Fiona Robson Cumbria County Council Jill Stannard Acting Chief Executive David Claxton Head of Member Services Angela Harwood Legal Services Paul Bell Media Officer Karen Rees Schools & Education HR Business Man David Sheard Area Support Manager Teresa Atkinson Labour Group Tony Wolfe Conservative Group Derek Houston Liberal Democrat Group Kate Astle Specialist Teaching Service Ruth Willey Senior Educational Psychologist Joan Lightfoot County Service Manager - Children wit Ana Harrison Speech Therapy Service Manager Ros Berry Children's Services Director & Commis Rose Foster Senior Specialist Advisory Teacher: De Marion Jones Autism Development Officer Angela Tunstall Department foe Children, Schools and Fran Gosling Thomas Children's -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring.