Male Gaze Theory and Ratmansky: Exploring Ballet's Ability to Adapt to a Feminist Viewpoint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danc Scapes Choreographers 2015

dancE scapes Choreographers 2015 Amy Cain was born in Jacksonville, Florida and grew up in The Woodlands/Spring area of Texas. Her 30+ years of dance training include working with various instructors and choreographers nationwide and abroad. She has also been coached privately and been inspired for most of her dance career by Ken McCulloch, co-owner of NHPA™. Amy is in her 22nd year of partnership in directing NHPA™, named one of the “Top 50 Studios On the Move” by Dance Teacher Magazine in 2006, and has also been co-director of Revolve Dance Company for 10 years. She also shares her teaching experience as a jazz instructor for the upper level students at Houston Ballet Academy. Amy has danced professionally with Ad Deum, DWDT, and Amy Ell’s Vault, and her choreographic works have been presented in Italy, Mexico, and at many Houston area events. In June 2014 Amy’s piece “Angsters”, performed by Revolve Dance Company, was presented as a short film produced by Gothic South Productions at the Dance Camera estW Festival in L.A. where it received the “Audience Favorite” award. This fall “Angsters” will be screened on Opening Night at the San Francisco Dance Film Festival in California, and on the first screening weekend at the Sans Souci Festival of Dance Cinema in Boulder, Colorado. Dawn Dippel (co-owner) has been dancing most of her life and is now co-owner of NHPA™, co-Director and founding member of Revolve Dance Company, and a former member of the Dominic Walsh Dance Theatre. She grew up in the Houston area, graduated from Houston’s High School for the Performing & Visual Arts Dance Department, and since then has been training in and outside of Houston. -

KC Dance Day Saturday, August 24Th Kansas City Ballet, Producer at the Todd Bolender Center for Dance & Creativity

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ellen McDonald 816.213.4355 [email protected] For Tickets: 816.931.8993 or www.kcballet.org KC Dance Day Saturday, August 24th Kansas City Ballet, Producer at the Todd Bolender Center for Dance & Creativity KANSAS CITY, MO (July 18, 2019) — Kansas City Ballet will kick-off its 62nd season with the 9th Annual KC Dance Day at the Todd Bolender Center for Dance & Creativity (500 W. Pershing, Kansas City, MO 64108) on Saturday, Aug. 24th from 9:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. The entire day will feature FREE dance performances, classes, demonstrations and FUN for the whole family. In addition, attendees may relax under a tent with food and beverages on sale from Two Guys and a Grill. “KC Dance Day is THE kick-off event of the new season,” Artistic Director Devon Carney said. “Well over a thousand Kansas Citians will join us for this open house and fun-filled day of dance featuring a multitude of Kansas City area dance organizations as well as many opportunities to join the fun. And as a bonus, our Company and Kansas City Ballet Second Company dancers will be in rehearsals so guests will get to see excerpts from the upcoming season.” KC Dance Day Schedule August 24, 2019 For more information, please visit our website at www.kcballet.org. FREE Children’s and Adult Dance Classes Doors open at 8:30 a.m. Classes start at 9:15 a.m. KC Dance Day Presented by Kansas City Ballet at the Todd Bolender Center for Dance & Creativity on Aug. -

October 2020 New York City Center

NEW YORK CITY CENTER OCTOBER 2020 NEW YORK CITY CENTER SUPPORT CITY CENTER AND Page 9 DOUBLE YOUR IMPACT! OCTOBER 2020 3 Program Thanks to City Center Board Co-Chair Richard Witten and 9 City Center Turns the Lights Back On for the his wife and Board member Lisa, every contribution you 2020 Fall for Dance Festival by Reanne Rodrigues make to City Center from now until November 1 will be 30 Upcoming Events matched up to $100,000. Be a part of City Center’s historic moment as we turn the lights back on to bring you the first digitalFall for Dance Festival. Please consider making a donation today to help us expand opportunities for artists and get them back on stage where they belong. $200,000 hangs in the balance—give today to double your impact and ensure that City Center can continue to serve our artists and our beloved community for years to come. Page 9 Page 9 Page 30 donate now: text: become a member: Cover: Ballet Hispánico’s Shelby Colona; photo by Rachel Neville Photography NYCityCenter.org/ FallForDance NYCityCenter.org/ JOIN US ONLINE Donate to 443-21 Membership @NYCITYCENTER Ballet Hispánico performs 18+1 Excerpts; photo by Christopher Duggan Photography #FallForDance @NYCITYCENTER 2 ARLENE SHULER PRESIDENT & CEO NEW YORK STANFORD MAKISHI VP, PROGRAMMING CITY CENTER 2020 Wednesday, October 21, 2020 PROGRAM 1 BALLET HISPÁNICO Eduardo Vilaro, Artistic Director & CEO Ashley Bouder, Tiler Peck, and Brittany Pollack Ballet Hispánico 18+1 Excerpts Calvin Royal III New York Premiere Dormeshia Jamar Roberts Choreography by GUSTAVO RAMÍREZ -

Dance Top Ten for 2015

Dance Top 10 for 2015: Women had an outsized role on this year's list Aparna Ramaswamy, co-artistic director of Ragamala Dance, in "Song of the Jasmine." (Alice Gebura) Laura Molzahn With shows by Wendy Whelan in January, Carrie Hanson in March, Onye Ozuzu in August, Twyla Tharp in November, and the female choreographers of Hubbard Street's winter program this weekend — well, 2015 has proved the year of the woman. That shouldn't be remarkable, because women predominate in dance, but it is. You'll find an unusually high number of additional picks by women in my chronological list below of the top 10 dance works of the last year — along with some fine representatives of the other sex. "Song of the Jasmine," Ragamala Dance, April at the Museum of Contemporary Art: Minneapolis-based mother-daughter team Ranee and Aparna Ramaswamy, collaborating with innovative composer-saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa, commingled jazz, carnatic music and bharata natyam dance in this synergistic, utterly contemporary evening-length piece. As a performer, Ramaswamy elicited the essence of the feminine; moving precisely, delicately, she used her hands and face so wholeheartedly you could smell heavenly jasmine yourself. "A Streetcar Named Desire," Scottish Ballet, May at the Harris Theater: In a brilliantly structured reimagining of the Tennessee Williams classic, choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, aided by theater and film director Nancy Meckler, wasted not a moment or a step as she created empathy with Blanche (no easy task) and with the story's gay lovers (unseen in the play). In this lush, emotional work — Lopez Ochoa's first full-length narrative ballet — the sparing use of point work gave it all the more impact. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria

Friday 24 April Sadler’s Wells Digital Stage An Evening with Natalia Osipova Valse Triste, Qutb & Ave Maria Natalia Osipova is a major star in the dance world. She started formal ballet training at age 8, joining the Bolshoi Ballet at age 18 and dancing many of the art form’s biggest roles. After leaving the Bolshoi in 2011, she joined American Ballet Theatre as a guest dancer and later the Mikhailovsky Ballet. She joined The Royal Ballet as a principal in 2013 after her guest appearance in Swan Lake. This showcase comprises of three of Natalia’s most captivating appearances on the Sadler’s Wells stage. Featuring Valse Triste, specially created for Natalia and American Ballet Theatre principal David Hallberg by Alexei Ratmansky, and the beautifully emotive Ave Maria by Japanese choreographer Yuka Oishi set to the music of Schubert, both of which premiered in 2018 at Sadler’s Wells’ as part of Pure Dance. The programme will also feature Qutb, a uniquely complex and intimate work by Sadler’s Wells Associate Artist Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, which premiered in 2016 as part of Natalia’s first commission alongside works by Arthur Pita and fellow Associate Artist Russell Maliphant. VALSE TRISTE, PURE DANCE 2018 Natalia Osipova Russian dancer Natalia Osipova is a Principal of The Royal Ballet. She joined the Company as a Principal in autumn 2013, after appearing as a Guest Artist the previous Season as Odette/Odile (Swan Lake) with Carlos Acosta. Her roles with the Company include Giselle, Kitri (Don Quixote), Sugar Plum Fairy (The Nutcracker), Princess Aurora (The Sleeping Beauty), Lise (La Fille mal gardée), Titania (The Dream), Marguerite (Marguerite and Armand), Juliet, Tatiana (Onegin), Manon, Sylvia, Mary Vetsera (Mayerling), Natalia Petrovna (A Month in the Country), Anastasia, Gamzatti and Nikiya (La Bayadère) and roles in Rhapsody, Serenade, Raymonda Act III, DGV: Danse à grande vitesse and Tchaikovsky Pas de deux. -

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 Pm

New York City Ballet MOVES Tuesday and Wednesday, October 24–25, 2017 7:30 pm Photo:Photo: Benoit © Paul Lemay Kolnik 45TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON 2017/2018 Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PETER MARTINS ARTISTIC ADMINISTRATOR JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH THE DANCERS PRINCIPALS ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING CHASE FINLAY ABI STAFFORD SOLOIST UNITY PHELAN CORPS DE BALLET MARIKA ANDERSON JACQUELINE BOLOGNA HARRISON COLL CHRISTOPHER GRANT SPARTAK HOXHA RACHEL HUTSELL BAILY JONES ALEC KNIGHT OLIVIA MacKINNON MIRIAM MILLER ANDREW SCORDATO PETER WALKER THE MUSICIANS ARTURO DELMONI, VIOLIN ELAINE CHELTON, PIANO ALAN MOVERMAN, PIANO BALLET MASTERS JEAN-PIERRE FROHLICH CRAIG HALL LISA JACKSON REBECCA KROHN CHRISTINE REDPATH KATHLEEN TRACEY TOURING STAFF FOR NEW YORK CITY BALLET MOVES COMPANY MANAGER STAGE MANAGER GREGORY RUSSELL NICOLE MITCHELL LIGHTING DESIGNER WARDROBE MISTRESS PENNY JACOBUS MARLENE OLSON HAMM WARDROBE MASTER MASTER CARPENTER JOHN RADWICK NORMAN KIRTLAND III 3 Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop Photo © Paul Kolnik for all of your instrument, EVENT SPONSORS accessory, and service needs! RICHARD AND MARY JO STANLEY ELLIE AND PETER DENSEN ALLYN L. MARK IOWA HOUSE HOTEL SEASON SPONSOR WEST MUSIC westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Photo: Miriam Alarcón Avila Season Sponsor! Play now. Play for life. We are proud to be your locally-owned, 1-stop shop for all of your instrument, accessory, and service needs! westmusic.com Cedar Falls • Cedar Rapids • Coralville Decorah • Des Moines • Dubuque • Quad Cities PROUD to be Hancher’s 2017-2018 Season Sponsor! THE PROGRAM IN THE NIGHT Music by FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN Choreography by JEROME ROBBINS Costumes by ANTHONY DOWELL Lighting by JENNIFER TIPTON OLIVIA MacKINNON UNITY PHELAN ABI STAFFORD AND AND AND ALEC KNIGHT CHASE FINLAY ADRIAN DANCHIG-WARING Piano: ELAINE CHELTON This production was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. -

Premieres on the Cover People

PDL_REGISTRATION_210x297_2017_Mise en page 1 01.06.17 10:52 Page1 Premieres 18 Bertaud, Valastro, Bouché, BE PART OF Paul FRANÇOIS FARGUE weighs up four new THIS UNIQUE ballets by four Paris Opera dancers EXPERIENCE! 22 The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas MIKE DIXON considers Daniel de Andrade's take on John Boyne's wartime novel 34 Swan Lake DEBORAH WEISS on Krzysztof Pastor's new production that marries a slice of history with Reece Clarke. Photo: Emma Kauldhar the traditional story P RIX 38 Ballet of Difference On the Cover ALISON KENT appraises Richard Siegal's new 56 venture and catches other highlights at Dance INTERNATIONAL BALLET COMPETITION 2017 in Munich 10 Ashton JAN. 28 TH – FEB. 4TH, 2018 AMANDA JENNINGS reviews The Royal DE Ballet's last programme in London this Whipped Cream 42 season AMANDA JENNINGS savours the New York premiere of ABT's sweet confection People L A U S ANNE 58 Dangerous Liaisons ROBERT PENMAN reviews Cathy Marston's 16 Zenaida's Farewell new ballet in Copenhagen MIKE DIXON catches the live relay from the Royal Opera House 66 Odessa/The Decalogue TRINA MANNINO considers world premieres 28 Reece Clarke by Alexei Ratmansky and Justin Peck EMMA KAULDHAR meets up with The Royal Ballet’s Scottish first artist dancing 70 Preljocaj & Pite principal roles MIKE DIXON appraises Scottish Ballet's bill at Sadler's Wells 49 Bethany Kingsley-Garner GERARD DAVIS catches up with the Consort and Dream in Oakland 84 Scottish Ballet principal dancer CARLA ESCODA catches a world premiere and Graham Lustig’s take on the Bard’s play 69 Obituary Sergei Vikharev remembered 6 ENTRE NOUS Passing on the Flame: 83 AUDITIONS AND JOBS 78 Luca Masala 101 WHAT’S ON AMANDA JENNINGS meets the REGISTRATION DEADLINE contents 106 PEOPLE PAGE director of Academie de Danse Princesse Grace in Monaco Front cover: The Royal Ballet - Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle in Ashton's Marguerite and Armand. -

Miami City Ballet 37

Miami City Ballet 37 MIAMI CITY BALLET Charleston Gaillard Center May 26, 2:00pm and 8:00pm; Martha and John M. Rivers May 27, 2:00pm Performance Hall Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez Conductor Gary Sheldon Piano Ciro Fodere and Francisco Rennó Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra 2 hours | Performed with two intermissions Walpurgisnacht Ballet (1980) Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Music Charles Gounod Staging Ben Huys Costume Design Karinska Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Katia Carranza, Renato Penteado, Nathalia Arja Emily Bromberg, Ashley Knox Maya Collins, Samantha Hope Galler, Jordan-Elizabeth Long, Nicole Stalker Alaina Andersen, Julia Cinquemani, Mayumi Enokibara, Ellen Grocki, Petra Love, Suzette Logue, Grace Mullins, Lexie Overholt, Leanna Rinaldi, Helen Ruiz, Alyssa Schroeder, Christie Sciturro, Raechel Sparreo, Christina Spigner, Ella Titus, Ao Wang Pause Carousel Pas de Deux (1994) Choreography Sir Kenneth MacMillan Music Richard Rodgers, Arranged and Orchestrated by Martin Yates Staging Stacy Caddell Costume Design Bob Crowley Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Jennifer Lauren, Chase Swatosh Intermission Program continues on next page 38 Miami City Ballet Concerto DSCH (2008) Choreography Alexei Ratmansky Music Dmitri Shostakovich Staging Tatiana and Alexei Ratmansky Costume Design Holly Hynes Lighting Design Mark Stanley Dancers Simone Messmer, Nathalia Arja, Renan Cerdeiro, Chase Swatosh, Kleber Rebello Emily Bromberg and Didier Bramaz Lauren Fadeley and Shimon Ito Ashley Knox and Ariel Rose Samantha -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Gp 3.Qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4

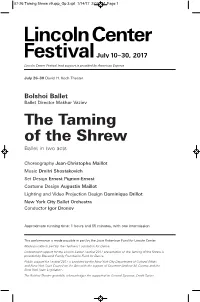

07-26 Taming Shrew v9.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/14/17 2:07 PM Page 1 Page 4 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 26–30 David H. Koch Theater Bolshoi Ballet Ballet Director Makhar Vaziev The Taming of the Shrew Ballet in two acts Choreography Jean-Christophe Maillot Music Dmitri Shostakovich Set Design Ernest Pignon-Ernest Costume Design Augustin Maillot Lighting and Video Projection Design Dominique Drillot New York City Ballet Orchestra Conductor Igor Dronov Approximate running time: 1 hours and 55 minutes, with one intermission This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Made possible in part by The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2017 presentation of The Taming of the Shrew is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2017 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. The Bolshoi Theatre gratefully acknowledges the support of its General Sponsor, Credit Suisse. 07-26 Taming Shrew.qxp_Gp 3.qxt 7/18/17 12:10 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2017 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Wednesday, July 26, 2017, at 7:30 p.m. The Taming of the Shrew Katharina: Ekaterina Krysanova Petruchio: Vladislav Lantratov Bianca: Olga Smirnova Lucentio: Semyon Chudin Hortensio: Igor Tsvirko Gremio: Vyacheslav Lopatin The Widow: Yulia Grebenshchikova Baptista: Artemy Belyakov The Housekeeper: Yanina Parienko Grumio: Georgy Gusev MAIDSERVANTS Ana Turazashvili, Daria Bochkova, Anastasia Gubanova, Victoria Litvinova, Angelina Karpova, Daria Khokhlova SERVANTS Alexei Matrakhov, Dmitry Dorokhov, Batyr Annadurdyev, Dmitri Zhuk, Maxim Surov, Anton Savichev There will be one intermission.