The Manchester Mill As 'Symbolic Form'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MANCHESTER WEEKENDER 14 Th/15 Th/16 Th/OCT

THE MANCHESTER WEEKENDER 14 th/15 th/16 th/OCT Primitive Streak Happy Hour with SFX Dr. Dee and the Manchester All The Way Home Infinite Monkey Cage Time: Fri 9.30-7.30pm, Sat 9.30-3.30pm Time: 5.30-7pm Venue: Royal Exchange Underworld walking tour Time: Fri 7.15pm, Sat 2.30pm & 7.15pm Time: 7.30pm Venue: University Place, & Sun 11-5pm Venue: Royal Exchange Theatre, St Ann’s Square M2 7DH. Time: 6-7.30pm Venue: Tour begins at Venue: The Lowry, The Quays M50 University of Manchester M13 9PL. Theatre, St Ann’s Square, window display Cost: Free, drop in. Harvey Nichols, 21 New Cathedral Street 3AZ. Cost: £17.50-£19.50. booking via Cost: Free, Booking essential through viewable at any time at Debenhams, M1 1AD. Cost: Ticketed, book through librarytheatre.com, Tel. 0843 208 6010. manchestersciencefestival.com. 123 Market Street. Cost: Free. jonathanschofieldtours.com. Paris on the Irwell Good Adolphe Valette’s Manchester Time: 6.30-8.30pm Venue: The Lowry, The Quays M50 3AZ. Cost: Free, Víctor Rodríguez Núñez Time: Fri 7.30pm, Sat 4pm & 8pm Time: 4-5.30pm Venue: Tour begins at booking essential thelowry.com. Time: 6.30pm Venue: Instituto Cervantes, Venue: Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester Art Gallery, Mosley Street, 326-330 Deansgate M3 4FN. Cost: Free, St Ann’s Square M2 7DH. Cost: £9-£33, M2 4JA. Cost: Ticketed, book through booking essential on 0161 661 4200. book through royalexchange.org.uk. jonathanschofieldtours.com. Culture Gym Unlocking Salford Quays Subversive Stitching Alternative Camera Club Crafternoon Tea Time: Various Venue: The Quays Cost: Time: 11am Venue: Meet in the foyer Time: 10am-12pm & 3-5pm Venue: Time: 11am-1pm Venue: Whitworth at The Whitworth £2.50. -

Manchester Metrolink Tram System

Feature New Promise of LRT Systems Manchester Metrolink Tram System William Tyson Introduction to Greater city that could be used by local rail into the city centre either in tunnel or on Manchester services—taking them into the central the street. area—to complete closure and I carried out an appraisal of these options The City of Manchester (pop. 500,000) is replacement of the services by buses. Two and showed that closure of the lines had at the heart of the Greater Manchester options were to convert some heavy rail a negative benefit-to-cost ratio, and that— conurbation comprised of 10 lines to light rail (tram) and extend them at the very least—they should be kept municipalities that is home to 2.5 million people. The municipalities appoint a Passenger Transport Authority (PTA) for the Figure 1 Metrolink Future Network whole area to set policies and the Greater 1 Victoria Manchester Passenger Transport Executive 2 Shudehill 3 Market Street Rochdale Town Centre 4 Mosley Street (GMPTE) to implement them. Buses Newbold Manchester 5 Piccadilly Gardens Drake Street Piccadilly Kingsway Business Park 6 Rochdale provide most public transport. They are 7 St Peter's Square Railway Milnrow Station deregulated and can compete with each 8 G-Max (for Castlefield) Newhey London 9 Cornbrook other and with other modes. There is a 0 Pomona Bury - Exchange Quay local rail network serving Manchester, and = Salford Quays Buckley Wells ~ Anchorage ! Harbour City linking it with the surrounding areas and @ Broadway Shaw and Crompton # Langworthy also other regions of the country. Street $ Tradfford Bar trams vanished from Greater Manchester % Old Trafford Radcliffe ^ Wharfside* & Manchester United* in 1951, but returned in a very different * Imperial War Museum for the North* ( Lowry Centre form in 1992. -

Download Brochure

RE – DEFINING THE WORK – PLACE Located on Quay Street, Bauhaus is an impressive Grade A office building that has been transformed to provide creative, flexible space for modern working. — 10 REASONS TO REDEFINE YOUR WORK PLACE LUXURY WELL CERTIFIED - GOLD CHANGING FACILITIES 3,000 SQ FT WIRED SCORE COMMUNAL PLATINUM ROOF TERRACE BUILDING INSIGHT SYSTEM OURHAUS – CONTINUOUS TESTING OF THE 1,400 SQ FT AIR QUALITY, HUMIDITY, CO-WORKING LOUNGE TEMPERATURE ULTRA-FAST FIBRE DEDICATED CONCIERGE BROADBAND SERVICE & ON-SITE BUILDING CONNECTIVITY MANAGEMENT TEAM FLEXIBLE SPACE CYCLING SCORE VARIETY OF LEASING OPTIONS PLATINUM 1:8 SQ M OCCUPATIONAL RATIO A new, warm and welcoming reception area allows occupiers to meet and greet in stylish surroundings. The informal meeting spaces in Ourhaus, our co-working business lounge area, allow a variety of interactions for your clients. — CONSIDERED OFFICES ARE CONDUCIVE TO GOOD WORK & WELLBEING The ground co-working business lounge area provides – Collaboration and co-working spaces ample scope for informal meetings and secluded work – Refurbished office floors to inspire areas, away from the main working space. creativity and efficiency This flexibility reduces an occupier’s need for in-situ – New impressive communal areas bespoke meeting rooms and allows variety and choice to be introduced to the working day. The roof terrace works as an — OUTDOOR excellent communal space for all our tenants, providing the perfect place for exercise and SOCIAL SPACES well-being, informal meetings PROMOTE HEALTH and social events. AND FITNESS WITHIN AN URBAN ENVIRONMENT The remodeled and upgraded building places — DESIGNED FOR the emphasis on workability and amenity. -

For Public Transport Information Phone 0161 244 1000

From 27 January Bus 84 New hourly Monday to Saturday daytime route introduced between 84 Chorlton Green, Chorlton, Hulme and Manchester city centre Easy access on all buses Chorlton Green Chorlton Whalley Range Hulme Manchester From 27 January 2019 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Diamond PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 19-0074–G84–2000–0119 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Diamond large print, Braille or recorded information Unit 22/23 Chanters Industrial Estate, phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Atherton M46 9BE Easy access on buses Telephone 01942 888893 Journeys run with low floor buses have no steps at the entrance, making getting on Travelshops and off easier. Where shown, low floor Manchester Piccadilly Gardens buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Sunday 10am to 6pm bus. The bus operator will always try to provide Public hols 10am to 5.30pm easy access services where these services are Manchester Shudehill Interchange scheduled to run. Mon to Sat 7am to 6pm Sunday Closed Using this timetable Public hols 10am to 1.45pm Timetables show the direction of travel, bus and 2.30pm to 5.30pm numbers and the days of the week. Main stops on the route are listed on the left. -

The Factory, Manchester

THE FACTORY, MANCHESTER The Factory is where the art of the future will be made. Designed by leading international architectural practice OMA, The Factory will combine digital capability, hyper-flexibility and wide open space, encouraging artists to collaborate in new ways, and imagine the previously unimagined. It will be a new kind of large-scale venue that combines the extraordinary creative vision of Manchester International Festival (MIF) with the partnerships, production capacity and technical sophistication to present innovative contemporary work year-round as a genuine cultural counterweight to London. It is scheduled to open in the second half of 2019. The Factory will be a building capable of making and presenting the widest range of art forms and culture plus a rich variety of technologies: film, TV, media, VR, live relays, and the connections between all of these – all under one roof. With a total floor space in excess of 15,000 square meters, high-spec tech throughout, and very flexible seating options, The Factory will be a space large enough and adaptable enough to allow more than one new work of significant scale to be shown and/or created at the same time, accommodating combined audiences of up to 7000. It will be able to operate as an 1800 seat theatre space as well as a 5,000 capacity warehouse for immersive, flexible use - with the option for these elements to be used together, or separately, with advanced acoustic separation. It will be a laboratory as much as a showcase, a training ground as well as a destination. Artists and companies from across the globe, as well as from Manchester, will see it as the place where they can explore and realise dream projects that might never come to fruition elsewhere. -

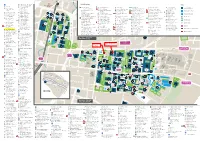

Building Key Key P

T S BAR ING S D TREET N L EE E R I G F K R IC I D W 35 Cordingley Lecture Theatre A RD A F 147 Building key A Key 86 Core Technology Facility Manchester Piccadilly Bus 78 Academy Station stop B 42 Cosmo Rodewald ERRY S cluster 63 Alan Gilbert 47 Coupland Building 3 83 Grove House 16 Manchester 53 Roscoe Building 81 The Manchester 32 Access Summit Concert Hall T Campus buildings Learning Commons 31 Crawford House 29 Harold Hankins Building Interdisciplinary Biocentre 45 Rutherford Building Incubator Building Disability Resource 01 Council Chamber cluster 46 Alan Turing Building 33 Crawford House Lecture 74 Holy Name Church 44 Manchester Museum cluster 14 The Mill Centre (Sackville Street) 01 Sackville Street Building University residences Theatres 76 AQA 80 Horniman House cluster 65 Mansfield Cooper Building 67 Samuel Alexander Building 37 University Place 37 Accommodation Office 51 Council Chamber cluster (Whitworth Building) 3 10 36 Arthur Lewis Building 867 Denmark Building 35 Humanities Bridgeford 42 Martin Harris Centre for 56 Schunck Building 38 Waterloo Place 31 Accounting and Finance A cluster cluster Principal car parks 6 15 P 68 Council Chamber 75 AV Hill Building T 41 Dental School and Hospital Street Music and Drama 11 Weston Hall 01 Aerospace Research E 54 Schuster Building (Students’ Union) E 30 Devonshire House AD 40 Information Technology 25 Materials Science Centre Centre (UMARI) 73 Avila House RC ChaplaTinRcy RO 59 Simon Building 84 Whitworth Art PC clusters S SON cluster 31 Counselling Service 2 G 70 Dover Street BuildWinAg -

Leading Artists Commissioned for Manchester International Festival

Press Release LEADING ARTISTS COMMISSIONED FOR MANCHESTER INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL High-res images are available to download via: https://press.mif.co.uk/ New commissions by Forensic Architecture, Laure Prouvost, Deborah Warner, Hans Ulrich Obrist with Lemn Sissay, Ibrahim Mahama, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Rashid Rana, Cephas Williams, Marta Minujín and Christine Sun Kim were announced today as part of the programme for Manchester International Festival 2021. MIF21 returns from 1-18 July with a programme of original new work by artists from all over the world. Events will take place safely in indoor and outdoor locations across Greater Manchester, including the first ever work on the construction site of The Factory, the world-class arts space that will be MIF’s future home. A rich online offer will provide a window into the Festival wherever audiences are, including livestreams and work created especially for the digital realm. Highlights of the programme include: a major exhibition to mark the 10th anniversary of Forensic Architecture; a new collaboration between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Lemn Sissay exploring the poet as artist and the artist as poet; Cephas Williams’ Portrait of Black Britain; Deborah Warner’s sound and light installation Arcadia allows the first access to The Factory site; and a new commission by Laure Prouvost for the redeveloped Manchester Jewish Museum site. Manchester International Festival Artistic Director & Chief Executive, John McGrath says: “MIF has always been a Festival like no other – with almost all the work being created especially for us in the months and years leading up to each Festival edition. But who would have guessed two years ago what a changed world the artists making work for our 2021 Festival would be working in?” “I am delighted to be revealing the projects that we will be presenting from 1-18 July this year – a truly international programme of work made in the heat of the past year and a vibrant response to our times. -

Official Directory. 2111

DIRECTORY.] OFFICIAL DIRECTORY. 2111 Nli. W CROSS WARD. WITHINGTON W ARD~ Alderman. Alderman. llWilliam Birkbeck, 70 North Porter street :j:Thomall Turnbull, 88 Mosley street Councillors. CauncIllorll. :l:Joseph Grime. 9 Albert square tStephen Edwards, 22 Alan road, Withington !John ThoUlas Jones, 2 Crescent grove, Levenshulme 0Harry Derwent Sirnpson. III ':it. Ann street • Arthur Ta) lor, 17 Hloom street tMiBB Margaret Ashton, 8 Kinnaird rd. Withington .Thom.... Wilson. 32 Corporation street Marked thus t retire in November l!lll tNathan Meadowcroft, 15 Oak street Marked thus" retire in November 1912 tThomas Robert Marr, 31 J;;ast avenue, Garden village, Burnage lane, Marked thus! retire in November 1913 Levensbulme Marked thus ~ retire in November 1!1l6 NEWTON HEATH WARD. Alderman not as~igned to a Ward-~Ohristopher Hornby, Lindum Alderman. House, Park road, Ashton·on Mersey UWilliam Trevor, 7 George street Quarterly Meetings of the Council for the Year 1911 :-Wednesdays, Councillors. 1st February, 3rd May, 2nd August· :l:Fredorlck Josepb West, Woningworth, Newton Heath 0Walter Butterworth, Barker street, Newton Heath tJoseph Arthur Moston, 83'1 Oldham rd. Newton Heath COMMITTEES OF THE COUNCIL. Appointed for the year 1910-1nl. OPENSHAW WARD. Alderman. ART GALLERY (fourteen members nominated by the Council) :j:JameB Filde~, Oak Lynn, South Downs road, Bowdon The Lord Mayor; Aldermen Carter, Goldschmidt and MOBS; Coun· Coui'l£ilwrs. cillors Abbott, Butterworth, J. W. Cook, HinchliIle, Lecomber, Litton, :j:George Frank Titt, 25 Cleveland avenue, Levenshulme Megson, Sir T. Thornhill Shann, Sirnpson and Todd; Marcus S. 0Tom Cook, Old Olough lane, Worsley Bles, 32 Ohorlton street: Professor S. -

Newsletter July/August 2018

‘What’s On’ Newsletter July/August 2018 A snapshot of activities going on in South Manchester Information compiled by the Community Inclusion Service Connect When it comes to wellbeing, other people matter. Evidence shows that good relationships with family, friends and the wider community, are important for mental wellbeing. Peer support social network group Tuesday Battery Park, Wilbraham Rd, M21 Drop in, in the morning Free. Drop-In, Tuesday The Tree of Life Centre Drop-in, Greenbrow Road, Newall Green, M23 2UE (meet at the café) 12-2pm. Friday Social Networking morning at the ‘Parrswood’, Parrswood Road, Didsbury Free Cafe Q, lunch meet up, Church Road, Northenden 12.00 Drop In at St Andrews House, Brownley Road M22 ODW 12.00 – 2.00 Saturday Self Help Drop-In, 9 Self Help Services, Wythenshawe Forum 10–12:00 Sunday Hall Lane Drop-In, 157 Hall Lane, Manchester, M23 1WD. 12-15.30 The free summer festival coming to a hidden square in Manchester Summer Jam 2018 will take place on Saturday 25th August between 12pm and 10pm The annual summer music festival that champions up-and-coming bands, street food and fun times will return to Sadler's Yard this month. Sadler's Yard Summer Jam, now in its third year, will have a brand new look and line-up for the bank holiday weekend celebrations. The festival is free but you'll need to register for a ticket. www.visitmanchester.com Sadler's Yard, Hanover Street, Manchester M60 0AB. Over 50s Barlow Moor Community Centre Over 60s Club 23 Mersey Bank Avenue, Chorlton, M21 7NT Phone: 0161 446 4805. -

Enjoy Free Travel Around Manchester City Centre on a Free

Every 10 minutes Enjoy free travel around (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) Monday to Friday: 7am – 10pm GREEN free QUARTER bus Manchester city centre Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm Every 12 minutes Manchester Manchester Victoria on a free bus Sunday and public holidays: Arena 9:30am – 6pm Chetham’s VICTORIA STATION School of Music APPROACH Victoria Every 10 minutes GREENGATE Piccadilly Station Piccadilly Station (Every 15 minutes after 6:30pm) CHAPEL ST TODD NOMA Monday to Friday: 6:30am – 10pm ST VICTORIA MEDIEVAL BRIDGE ST National Whitworth Street Sackville Street Campus Saturday: 8:30am – 10pm QUARTER Chorlton Street The Gay Village ootball Piccadilly Piccadilly Gardens River Irwell Cathedral Chatham Street Manchester Visitor Every 12 minutes useum BAILEYNEW ST Information Centre Whitworth Street Palace Theatre Sunday and public holidays: orn The India House 9:30am – 6pm Exchange Charlotte Street Manchester Art Gallery CHAPEL ST Salford WITHY GROVEPrintworks Chinatown Portico Library Central MARY’S MARKET Whitworth Street West MMU All Saints Campus Peak only ST Shudehill GATE Oxford Road Station Monday to Friday: BRIDGE ST ST Exchange 6:30 – 9:10am People’s Suare King Street Whitworth Street West HOME / First Street IRWELL ST History Royal Cross Street Gloucester Street Bridgewater Hall and 4 – 6:30pm useum Barton Exchange Manchester Craft & Manchester Central DEANSGATE Arcade/ Arndale Design Centre HIGH ST Deansgate Station Castlefield SPINNINGFIELDS St Ann’s Market Street Royal Exchange Theatre Deansgate Locks John Suare Market NEW Centre -

Infra Mancrichard Brook + Martin Dodge PICC-VIC TUNNEL

Futurebound Services HELIPORT MANCUNIAN WAY Infra_MANCRichard Brook + Martin Dodge PICC-VIC TUNNEL GUARDIAN EXCHANGE Catalogue to accompany the exhibition CUBE Gallery | RIBA Hub Spring 2012 Infra_MANC Infra_MANC Post-war infrastructures of Manchester The catalogue of Infra_MANC. An exhibition at the RIBA Hub / CUBE Gallery, Portland Street Manchester from 27th February – 17th March 2012. Curated by Richard Brook and Martin Dodge Richard Brook Manchester School of Architecture, John Dalton West, Chester Street, Manchester. M1 5GD, UK. Martin Dodge Department of Geography, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK. Infra_MANC Prelims Second edition 2012 © Richard Brook and Martin Dodge 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Richard Brook and Martin Dodge have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors and editors of this work. Published by bauprint 34 Milton Road Prestwich Manchester M25 1PT ISBN 978-0-9562913-2-5 Prelims Infra_MANC Table of contents Acknowledgements Curator biographies Introduction and overview map Timeline Ch.001 Helicopter Dreaming Ch.002 Mancunian Way [A57(M)] Our Highway in the Sky Ch.003 The Picc-Vic Tunnel Ch.004 Guardian Underground Telephone Exchange Bibliography List of exhibits Exhibition photos Infra_MANC Prelims ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Copyright The exhibition and catalogue are an academic project and were undertaken on a non-commercial basis. We have assembled visual materials from a large number of sources and have endeavoured to secure suitable permissions. -

Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society Vol

Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society Vol. 111, 2019 Wyke, Terry; Robson, Brian & Dodge, Martin, Manchester: mapping the city. Edinburgh: Berlinn, 2018. 256p, maps, plans, photos, tables. Hbk. £30.00. ISBN 978-1-78027-530-7. ‘The purpose of this volume is to invite readers to use their eyes and imagination to look at a selection of the published and manuscript maps and plans of the rich and extensive cartography of Manchester, ranging from the eighteenth century to the present day’. This aim, from the Introduction to this book, is more than realised, as you would expect from this triumvirate of writers, all experts in their field. Terry Wyke is Honorary Research Fellow at Manchester Metropolitan University, one of the founder-editors of the Manchester Region History Review, and has written and published extensively on the history of the Manchester area. Brian Robson is Emeritus Professor at Manchester University and has published extensively on urban regeneration. In 1983 he founded the Centre for Urban Policy Studies; now retired, he researches a long-held interest in historic urban cartography. Martin Dodge, Senior Lecturer in Geography at Manchester University, currently researches on Manchester and has curated a number of high-profile public exhibitions about the city. Most of the maps come from the city’s various and varied collections – Chetham’s Library, Manchester Libraries and Archives, and the University of Manchester Library, whose map collection numbers in excess of 150,000 items including a significant collection of maps relating to Manchester and the surrounding area, together with items from the authors’ own collections, and those of other local individuals and organisations – while some are from further afield: the National Library of Scotland, the British Library, the Government Art Collection, and The National Archives are credited sources.