City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDICE -.:: Biblioteca Virtual Espírita

INDICE A CIÊNCIA DO FUTURO......................................................................................................................................... 4 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPIRITISMO................................................................................................................................ 5 A PALAVRA DOS CIENTISTAS ..................................................................................................................... 6 UMA NOVA CIÊNCIA...................................................................................................................................... 7 O ESPIRITISMO ............................................................................................................................................. 8 O ESPIRITISMO E A METAPSÍQUICA........................................................................................................... 8 O ESPIRITISMO E PARAPSICOLOGIA ......................................................................................................... 9 A CIÊNCIA E O ESPÍRITO .................................................................................................................................... 10 A CIÊNCIA ESPÍRITA OU DO ESPÍRITO ............................................................................................................. 13 1. ALLAN KARDEC E A DEFINIÇÃO DO ESPIRITISMO, SOB O ASPECTO CIENTÍFICO......................... 14 2. A CIÊNCIA E SEUS MÉTODOS. ............................................................................................................. -

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

Encyclopedia of Ancient and Forbidden Secrets Nye Abraham, the Jew: (Alchemist and Magician, Circa, 1400)

www.GetPedia.com Encyclopedia of Ancient and Forbidden Secrets Nye Abraham, The Jew: (Alchemist and magician, circa, 1400). work this consisting of some account of Abraham's youth and early Comparatively few biographical facts are forthcoming concerning travels in search of wisdom, along with advice to the young man this German Jew, who was at once alchemist, magician and aspiring to become skilled in occult arts. The second part, on the philosopher; and these few facts are mostly derived from a very other hand, is base on the documents which the Egyptian sage curious manuscript, now domiciled in the Archives of the handed the Jew, or at least on the confidences wherewith the Bibliotheque de l'Arsenal, Paris, an institution rich in occult former favoured the latter; and it may be fairly accurately defined documents. This manuscript is couched throughout in French, but as dealing with the first principles of magic in general, the titles of purports to be literally translated from Hebrew, and the style of the some of the more important chapter being as follows: " How Many, handwriting indicates that the scribe lived at the beginning of the and what are the Classe of Veritable Magic ? " - What we Ought to eighteenth century, or possibly somewhat earlier. Take int Consideration before the Undertaking of the Operation, " Concerning the Convocation of the Spirits, " and " I what Manner A distinct illiteracy characterises the French script, the we ought to Carry out the Operations. punctuation being inaccurate, indeed frequently conspicuous by its absence, but an actual description of the document must be Passing to the third and last part, this likewise is most derived waived till later. -

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: a Late Modern Enchantment

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: A Late Modern Enchantment Daniel S. Wise New Haven, CT Bachelor oF Arts, Florida State University, 2010 Master oF Arts, Florida State University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty oF the University oF Virginia in Candidacy For the Degree oF Doctor oF Philosophy Department oF Religious Studies University oF Virginia November, 2020 Committee Members: Erik Braun Jack Hamilton Matthew S. Hedstrom Heather A. Warren Contents Acknowledgments 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 5 Chapter 2 From Spiritualism to Ghost Hunting 27 Chapter 3 Ghost Hunting and Scientism 64 Chapter 4 Ghost Hunters and Demonic Enchantment 96 Chapter 5 Ghost Hunters and Media 123 Chapter 6 Ghost Hunting and Spirituality 156 Chapter 7 Conclusion 188 Bibliography 196 Acknowledgments The journey toward competing this dissertation was longer than I had planned and sometimes bumpy. In the end, I Feel like I have a lot to be thankFul For. I received graduate student Funding From the University oF Virginia along with a travel grant that allowed me to attend a ghost hunt and a paranormal convention out oF state. The Skinner Scholarship administered by St. Paul’s Memorial Church in Charlottesville also supported me For many years. I would like to thank the members oF my committee For their support and For taking the time to comb through this dissertation. Thank you Heather Warren, Erik Braun, and Jack Hamilton. I especially want to thank my advisor Matthew Hedstrom. He accepted me on board even though I took the unconventional path oF being admitted to UVA to study Judaism and Christianity in antiquity. -

Spiritualism : Is Communication with the Spirit World an Established Fact?

ti n Is Communhatm with Be an established fact? flRH ^H^^^^^H^K^^^^^^^^^^I^^B^^H^^^I^^^^^^^B^^^^HI^^^^^H bl™' ^^^^^H^^HHS^^ffiiyS^^H^^^^^^^^^I^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^BH^^BiHwv^ 1 f \ 1 PRO—WAKE COOK^H hi ''^KSBm 1 CON FRANK P0DM0rE9I i 1 l::| - ; Hodgson, AMEfilC^^ secret; ^, FLAub, B BOYLSTOtl BOSTOxM, MASS. Boston Medical Library 8 The Fenway The Pro and Con Series EDITED BY HENRY MURRAY VOL. II. /l 6 Br SPIRITUALISM " ^ SPIRITUALISM IS COMMUNICATION WITH THE SPIRIT WORLD AN ESTABLISHED FACT? PRO—E. WAKE COOK AUTHOR OF '•' THE OEGANISATION OF MAlfKIND " 'THE INCREASING PURPOSE" ETC. CON—FRANK PODMORE AUTHOR OF " MODERN SPIRITUALISM " " STUDIES IN PSYCHICAL RESEARCH" ETC. AUDI ALTERAM PARTEM LONDON ISBISTER AND COMPANY LIMITED 15 & 16 TAVISTOCK ST. COVENT GARDEN 1903 / 9. cA:/d9, Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> Co. London <&» Edinburgh '-OCIETY FO.- KEbt-i^i^^^- f5 BOVi-^S-V.ss. BOSTON. SPIRITUALISM—PRO BY E. WAKE COOK A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/spiritualismiscoOOcook SPIRITUALISM IS COMMUNICATION WITH THE SPIRIT-WORLD AN ESTABLISHED FACT? PRO PAKT I The mystery of Existence deepens. Physical Science, whose splendid advance promised to make all things clear, is taking us into mys- terious wonder-worlds, revealing profounder depths than were ever dreamt of in our philosophies, and making greater and greater demands on our powers of belief. Materialism, never either philosophically or scientifically sound, seems now to be suspended in mid-air like Mahomet's coffin. What is matter ? No one can tell us ; Sir Oliver Lodge asserting that we know more of electricity than of matter. -

Note on the Intellectual Work of William Stainton Moses

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 596–603, 2018 0892-3310/18 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Note on the Intellectual Work of William Stainton Moses CARLOS S. ALVARADO Parapsychology Foundation [email protected] Submitted February 13, 2018; Accepted March 14, 2018; Published September 30, 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31275/2018/1300 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC-ND Abstract—Most discussions about William Stainton Moses have focused on his mediumship. This note is a reminder that, in addition to medium- ship, such as the spirit communication recorded in Spirit Teachings (1883), he contributed in other ways to the study of psychic phenomena, includ- ing studies of direct writing, materializations, and spirit photography. Furthermore, Moses wrote about apparitions of the living and out-of-body experiences, and veridical mediumistic communications, and criticized the writings of others, among them physiologist William B. Carpenter. A con- sideration of this and other neglected aspects of Moses’ work, enlarges our view of his contributions to Nineteenth-Century British Spiritualism and psychical research. Introduction In a previous paper published in the JSE, I discussed the fact that some individuals connected to the history of psychical research are sometimes neglected in historical accounts (Alvarado 2012). I also mentioned that some historical figures are only partially remembered for aspects of their work, to the detriment of others. One example I briefly discussed, and which I would like to present more information about here, is William Stainton Moses. Reverend William Stainton Moses (1839–1892) has generally been discussed as a medium (e.g., Myers 1894–1895, Tymn 2015). -

The History Spiritualism

THE HISTORY of SPIRITUALISM by ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, M.D., LL.D. former President d'Honneur de la Fédération Spirite Internationale, President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science Volume Two With Eight Plates Sir Arthur Conon Doyle CHAPTER I THE CAREER OF EUSAPIA PALLADINO The mediumship of Eusapia Palladino marks an important stage in the history of psychical research, because she was the first medium for physical phenomena to be examined by a large number of eminent men of science. The chief manifestations that occurred with her were the movement of objects without contact, the levitation of a table and other objects, the levitation of the medium, the appearance of materialized hands and faces, lights, and the playing of musical instruments without human contact. All these phenomena took place, as we have seen, at a much earlier date with the medium D. D. Home, but when Sir William Crookes invited his scientific brethren to come and examine them they declined. Now for the first time these strange facts were the subject of prolonged investigation by men of European reputation. Needless to say, these experimenters were at first sceptical in the highest degree, and so-called ‘tests’ (those often silly precautions which may defeat the very object aimed at) were the order of the day. No medium in the whole world has been more rigidly tested than this one, and since she was able to convince the vast majority of her sitters, it is clear that her mediumship was of no ordinary type. -

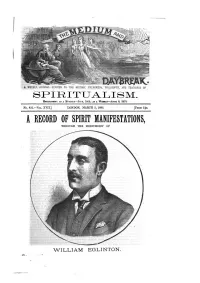

The Medium and Daybreak

A WEEKLY JOURNAL DEVOTED TO THE HISTORY, PHENOMENA, PHILOSOPHY, AND TEACHINGS OF . .. SPIRITUALISM. EsTilLISB.ED: AS A MoNTHLY-Juu, 1868; AS A W&ULY-APBIL 8, 1870. No. 831.-VoL. XVII.] LONDON, MARCH 5, 1886. [PlllCB lin. A RECORD OF SPIRIT MANIFESTATIONS, THROUGH THE MEDIUMSHIP OF \/VILLIAM .EGLINTON: ~ -·: 146 THE MED1t1M: AND I>AYBREAK. MuoH 5, 1886. sitters, retain the services of a medium and uevelop as be WILLIAM EGLINTON'S MEDIUMSHIP. develops, then the phenomena may take place in the circle and amongst the sitters, because the sphere of manifestation Unlike many other remarkable. mediums, 1'_fr. Eglinton's includes the whole. Mentally, the sitters are prepared by wonderful gifts cannot be traced as hereditary, though their past experiences for whatever may occur. There are possibly it may be found that indications of mediumship no suspicions nor doubts ; and the personal emanations are existed on his mother's side. His descent is traced from the kept in sympathy and fulness of degree. · Thie is the true Montgomeries, of Eglinton Castle, Ayrshire. This may be spirit circle; and when Spiritualists becom~ true to their regarded as a positive quality of temperament, which when title they will have no other : then spirits will manifest dnly blended with the sensitive, gives the best balance and the spontaneously, and in a variety of forms-solid, semi-solid soundest basis for mediumship. or di4phanoue. Such things have occurred with many Mr. Eglinton's early training kept his mind free from mediums. But the "investigator" wants to pluck the fruit theological prejudices, his bias, if any, being in the opposite before it is ripe. -

Hamiltont.Pdf

1 A critical examination of the methodology and evidence of the first and second generation elite leaders of the Society for Psychical Research with particular reference to the life, work and ideas of Frederic WH Myers and his colleagues and to the assessment of the automatic writings allegedly produced post-mortem by him and others (the cross- correspondences). Submitted by Trevor John Hamilton to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Publication (PT) in June 2019.This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and no material has been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature…………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis outlines the canons of evidence developed by the elite Cambridge- based and educated leaders of the Society for Psychical Research to assess anomalous phenomena, and second, describes the gradual shift away from that approach, by their successors and the reasons for such a partial weakening of those standards, and the consequences for the general health of the SPR .It argues that, for a variety of reasons, this methodology has not always been fully appreciated or described accurately. Partly this is to do with the complex personality of Myers who provoked a range of contradictory responses from both contemporaries and later scholars who studied his life and work; partly to do with the highly selective criticisms of his and his colleagues’ work by TH Hall (which criticisms have entered general discourse without proper examination and challenge); and partly to a failure fully to appreciate how centrally derived their concepts and approaches were from the general concerns of late-Victorian science and social science. -

Download an Issue

ISSN 2311 – 3448 and RELIGION STATE, CHURCH ation R STATE, dminist a RELIGION ublic P and ARTICLES and Yury Khalturin. Esotericism and the Mapping the Worldview of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth- Imaginaire at the Frontiers of Science: Century Russian Freemasonry: Toward The Quest for Universal Unity at the Turn conomy CHURCH a Conceptualization e of the Twentieth Century (Review Article) Ekateryna Zorya. Magic in the Post-Soviet Russian Rodnoverie: Neo-Paganism and ational Markers n Nationalism in Today’s Russia. (Russkoe rodnoverie: Neoiazichestvo i natsionalizm of Alexey Glushaev. “Without Preachers, in a Corner of the Barracks”: Protestant v sovremennoi Rossii). Moscow: “Barracks Congregations” in the Perm-Kama Region in the Second Half of cademy a the 1940s through the Early 1960s Orthodox Galina Zelenina. “One’s Entire Life among Christianity and the Institutions of Power Books”: Soviet Jewry on the Path from and Civil Society in Russia. (Pravoslavie, instituty vlasti i grazhdanskogo esidential R LECTURE P Bernice Martin. Religion, Secularity and Cultural Memory in Brazil ussian R R ussian PR esidential a cademy of n ational e conomy and Public a dministR ation RELIGION CHURCH Vol. 1 Vol. STATE, and Moscow, 2014 Moscow, ISSN (2) 2311 2014 – 3448 EDITORS Dmitry Uzlaner (editor-in-chief ), Christopher Stroop (editor), Alexander Agadjanian, Alexander Kyrlezhev DESIGN Sergey Zinoviev, Ekaterina Trushina LAYOUT Anastasia Akimova State, Religion and Church is an academic peer- reviewed journal devoted to the interdisciplinary scholarly study of religion. Published twice yearly under the aegis of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration. EDITORIAL BOARD Alexey Beglov (Russia), Mirko Blagojević (Serbia), Thomas Bremer (Germany), Grace Davie (UK), Vyacheslav Karpov (USA), Vladimir Malyavin (China), Brian Horowitz (USA), Vasilios Makrides (Germany), Bernice Martin (UK), David Martin (UK), Alexander Panchenko (Russia), Randall A. -

Human Levitation

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2005 Human levitation Simon B. Harvey-Wilson Western Australian College of Advanced Education Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Harvey-Wilson, S. B. (2005). Human levitation. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/642 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/642 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2005 Human levitation Simon B. Harvey-Wilson Western Australian College of Advanced Education Recommended Citation Harvey-Wilson, S. B. (2005). Human levitation. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/642 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/642 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Historical Notes on Psychic Phenomena in Specialised Journals

European Journal of Parapsychology c 2006 European Journal of Parapsychology Volume 21.1, pages 58–87 ISSN: 0168-7263 Historical Notes on Psychic Phenomena in Specialised Journals Carlos S. Alvarado∗, Massimo Biondi∗∗ and Wim Kramer† ∗Division of Perceptual Studies, University of Virginia Health System ∗∗Rome, Italy †Bunnik, The Netherlands Abstract This paper presents brief information about the existence and ori- entation of selected journals that have published articles on psychic phenomena. Some journals emphasize particular theoretical ideas, or methodological approaches. Examples include the Journal du magn´etismeand Zoist, in which animal magnetism was discussed, and the Revue Spirite, and Luce e Ombra, which focused on discar- nate agency. Nineteenth-century journals such as the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research and the Annales des Sciences Psychiques emphasized both methodology and the careful accumu- lation of data. Some publications, such as the Journal of the Amer- ican Society for Psychical Research and the Dutch Tijdschrift voor Parapsychologie, were influenced by the agenda of a single individ- ual. Other journals represented particular approaches or points of view, such as those of spiritualism (Luce e Ombra and Psychic Sci- ence), experimental parapsychology (Journal of Parapsychology), or skepticism (Skeptical Inquirer). An awareness of the differing char- acteristics of these publications illustrates aspects of the development of parapsychology as a discipline. Correspondence details: Carlos S. Alvarado, Division of Perceptual Studies, Department of Psychi- atric Medicine, University of Virginia Health System, P.O. Box 800152, Charlottesville, VA, 22908, USA. Email: [email protected]. 58 Alvarado, Biondi & Kramer Introduction With the rise of modern interest in psychic phenomena, several spe- cialised journals were created both to put on record the existence and investigation of such happenings, and to provide a venue for serious discussion of them.