Download PDF (916.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

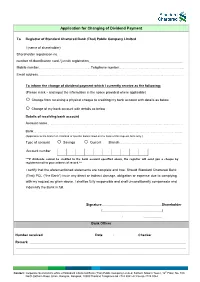

Application for Changing of Dividend Payment

Application for Changing of Dividend Payment To Registrar of Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) Public Company Limited I (name of shareholder) Shareholder registration no. number of identification card / juristic registration Mobile number………………………………………………….……….....Telephone number…………………..……………………………………….……………….. Email address……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………… To inform the change of dividend payment which I currently receive as the following: (Please mark and input the information in the space provided where applicable) Change from receiving a physical cheque to crediting my bank account with details as below Change of my bank account with details as below Details of receiving bank account Account name………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….….. Bank………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………….... (Applicable to the branch in Thailand of specific banks listed on the back of this request form only.) Type of account Savings Current Branch…………………………………………………….……………………. Account number ***If dividends cannot be credited to the bank account specified above, the registrar will send you a cheque by registered mail to your address of record.*** I certify that the aforementioned statements are complete and true. Should Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) PCL (“the Bank”) incur any direct or indirect damage, obligation or expense due to complying with my request as given above. I shall be fully responsible and shall unconditionally compensate and indemnify the Bank in full. Signature Shareholder ( ) / / Bank Officer Number received Date / / Checker Remark Contact: Corporate Secretariat’s office of Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) Public Company Limited, Sathorn Nakorn Tower, 12th Floor, No. 100 North Sathorn Road, Silom, Bangrak, Bangkok, 10500 Thailand Telephone 66 2724 8041-42 Fax 66 2724 8044 Documents to be submitted for changing of dividend payment (All photocopies must be certified as true) For Individual Person 1. -

Investor Presentation As of 1Q13

KASIKORNBANK Investor Presentation as of 1Q13 July 2013 For further information, please contact the Investor Relations Unit or visit our website at www.kasikornbankgroup.com or www.kasikornbank.com 1 KASIKORNBANK at a Glance Established on June 8, 1945 with registered capital of Bt5mn (USD 0.17mn) Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) since 1976 Consolidated (as of March 2013) Asse ts Bt2,110bn (USD72.0bn) Ranked #4 with 14.7% market share** Loans* Bt1,356bn (USD46.3bn) Ranked #4 with 14.8% market share** Deposits Bt1,428bn (USD48.7bn) Ranked #4 with 15.1% market share** CAR 15.79% *** ROE (1Q13) 21.23% ROA (1Q13) 1.93% Number of Branches 877 Number of ATMs 7,689 Number of Employees 17,718 Share Information SET Symbol KBANK, KBANK-F Share Capital: Authorized Bt30.5bn (USD1.0bn) Issued and Paid-up Bt23.9bn (USD0.8bn) Number of Shares 2.4bn shares Market Capitalization Bt498bn (USD17.0bn) Ranked #2 in Thai banking sector 1Q13 Avg. Share Price: KBANK Bt204.75 (USD6.99) KBANK-F Bt206.72 (USD7.05) EPS (1Q13) Bt4.22 (USD0.14) BVPS Bt81.85 (USD2.79) Notes: * Loans = Loans to customers less Deferred revenue ** Assets, loans and deposits market share is based on C.B.1.1 (Monthly statement of assets and liabilities) *** Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) has been reported in accordance with Basel III Capital Requirement from 1 January 2013 onwards. CAR is based on KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE. KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE means the company under the Notification of the Bank of Thailand re: Consolidated Supervision, consisted of KBank, K Companies and subsidiaries operating in supporting KBank, Phethai Asset Management Co., Ltd. -

Fixed Income Investor Presentation

KASIKORNBANK Fixed Income Investor Presentation September 2019 For further information, please contact the Investor Relations Unit or visit our website at www.kasikornbank.com 1 KASIKORNBANK at a Glance Established on June 8, 1945 with registered capital of Bt5mn (USD0.16mn) Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) since 1976 Consolidated (as of June 2019) Assets Bt3,256bn (USD105.9bn) Ranked #3 with 15.5% market share** Loans* Bt1,933bn (USD62.9bn) Ranked #4 with 15.1% market share** Deposits Bt2,005bn (USD65.2bn) Ranked #3 with 15.8% market share** CAR 18.55% *** ROE (1H19) 10.35% ROA (1H19) 1.25% Number of Branches 882 Number of ATMs 8,840 Number of K PLUS Users 11.1mn Number of Employees 20,352 Share Information SET Symbol KBANK, KBANK-F Share Capital: Authorized Bt30.5bn (USD1.0bn) Issued and Paid-up Bt23.9bn (USD0.8bn) Number of Shares 2.4bn shares Market Capitalization Bt449bn (USD14.6bn) Ranked #2 in Thai banking sector 2Q19 Avg. Share Price: KBANK Bt190.00 (USD6.18) KBANK-F Bt190.58 (USD6.20) EPS (1H19) Bt8.35 (USD0.27) BVPS Bt165.40 (USD5.38) Notes: * Loans = Loans to customers less deferred revenue ** Assets, loans and deposits market share is based on C.B.1.1 (Monthly statement of assets and liabilities) of 14 Thai commercial banks as of June 2019 *** Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) has been reported in accordance with Basel III Capital Requirement from 1 January 2013 onwards. CAR is based on KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE. KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE means the company under the Notification of the Bank of Thailand re: Consolidated Supervision, consisted of KBank, K Companies and subsidiaries operating in supporting KBank, Phethai Asset Management Co., Ltd. -

For the Year Ended 31 December 2019 Siam Commercial Bank

Annual Registration Statement (Form 56-1) For the Year Ended 31 December 2019 Siam Commercial Bank Public Company Limited The Siam Commercial Bank Public Company Limited 9 Ratchadapisek Road, Jatujak, Bangkok 10900 Thailand Tel. +66 2 544-1000 Website: www.scb.co.th Siam Commercial Bank Public Company Limited Annual Registration Statement (Form 56-1) Ended 31 December 2019 Contents PART 1 COMPANY'S BUSINESS 1. Policy and Business Overview ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Nature of Business Performance ...................................................................................................... 4 3. Risk Factors .................................................................................................................................... 18 4. Business Assets ............................................................................................................................. 37 5. Legal Dispute .................................................................................................................................. 44 6. General Information ........................................................................................................................ 45 PART 2 MANAGEMENT AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 7. Securities and Shareholders .......................................................................................................... 49 8. Organization Structure ................................................................................................................... -

Investor Presentation As of 2Q17

KASIKORNBANK Investor Presentation as of 2Q17 August 2017 For further information, please contact the Investor Relations Unit or visit our website at www.kasikornbank.com 1 KASIKORNBANK at a Glance Established on June 8, 1945 with registered capital of Bt5mn (USD 0.14mn) Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) since 1976 Consolidated (as of June 2017) Assets Bt2,853bn (USD84.0bn) Ranked #4 with 15.1% market share** Loans* Bt1,752bn (USD51.6bn) Ranked #4 with 15.2% market share** Deposits Bt1,839bn (USD54.1bn) Ranked #4 with 15.8% market share** CAR 17.63% *** ROE (1H17) 11.68% ROA (1H17) 1.34% Number of Branches 1,056 Number of ATMs 9,026 Number of Employees 20,760 Share Information SET Symbol KBANK, KBANK-F Share Capital: Authorized Bt30.5bn (USD0.9bn) Issued and Paid-up Bt23.9bn (USD0.7bn) Number of Shares 2.4bn shares Market Capitalization Bt475bn (USD14.0bn) Ranked #2 in Thai banking sector 2Q17 Avg. Share Price: KBANK Bt190.43 (USD5.60) KBANK-F Bt191.07 (USD5.62) EPS (1H17) Bt8 (USD0.24) BVPS Bt139.62 (USD4.11) Notes: * Loans = Loans to customers less Deferred revenue ** Assets, loans and deposits market share is based on C.B.1.1 (Monthly statement of assets and liabilities) of 14 Thai commercial banks as of June 2017 *** Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) has been reported in accordance with Basel III Capital Requirement from 1 January 2013 onwards. CAR is based on KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE. KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE means the company under the Notification of the Bank of Thailand re: Consolidated Supervision, consisted of KBank, K Companies and subsidiaries operating in supporting KBank, Phethai Asset Management Co., Ltd. -

Ifn Sector Correspondents Ifn Country

IFNIFN COUNTRY SECTOR CORRESPONDENTS A positive first quarter IFN Country Correspondents AUSTRALIA: Gerhard Bakker director, Madina Village Community Services QATAR its joint venture Maran Nakilat Co., has BAHRAIN: Dr Hatim El-Tahir director of Islamic Finance Knowledge Center, Deloitt e & added three new LNG vessels to its fl eet. Touche By Amjad Hussain BANGLADESH: Md Shamsuzzaman Barwa Real Estate Company, a Qatar executive vice president, Islami Bank Bangladesh Exchange-listed Shariah compliant real BELGIUM: Prof Laurent Marliere Qatar recently announced its budget CEO, ISFIN estate investor has signed a deal worth for 2014-15 at around US$62 billion, BERMUDA: Belaid A Jheengoor around US$2.08 billion to sell its Barwa director of asset management, PwC an increase of around 3.5% over the BRUNEI: James Chiew Siew Hua City real estate project to Labregah senior partner, Abrahams Davidson & Co last fi scal year. While the budget has a CANADA: Jeff rey S Graham Real Estate, a wholly-owned subsidiary signifi cant focus on the infrastructure partner, Borden Ladner Gervais Qatari Diar. Qatar's largest telecoms EGYPT: Dr Walid Hegazy sector, its growth is indicative of the managing partner, Hegazy & Associates operator Ooredoo has also signed three FRANCE: Kader Merbouh government’s support for the growth co head of the executive master of the Islamic fi nance, Paris- one-year Murabahahs of US$166 million: of the wider economy and particularly Dauphine University one with each of Qatar Islamic Bank, HONG KONG & CHINA: Anthony Chan that of the fi nancial sector. This can founder, New Line Capital Investment Limited Masraf Al-Rayyan and Barwa Bank. -

RF Islamic Finance 112009.Book

Bala Shanmugam Monash University Zaha Rina Zahari RBS Coutts A Primer on Islamic Finance Statement of Purpose The Research Foundation of CFA Institute is a not-for-profit organization established to promote the development and dissemination of relevant research for investment practitioners worldwide. Neither the Research Foundation, CFA Institute, nor the publication’s editorial staff is responsible for facts and opinions presented in this publication. This publication reflects the views of the author(s) and does not represent the official views of the Research Foundation or CFA Institute. The Research Foundation of CFA Institute and the Research Foundation logo are trademarks owned by The Research Foundation of CFA Institute. CFA®, Chartered Financial Analyst®, AIMR-PPS®, and GIPS® are just a few of the trademarks owned by CFA Institute. To view a list of CFA Institute trademarks and the Guide for the Use of CFA Institute Marks, please visit our website at www.cfainstitute.org. ©2009 The Research Foundation of CFA Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. ISBN 978-1-934667-24-8 4 December 2009 Editorial Staff Elizabeth Collins Book Editor David L. -

Thai Commercial Banks and Specialized Financial Institutions (Sfis)

KASIKORNBANK Investor Presentation as of 3Q18 October 2018 For further information, please contact the Investor Relations Unit or visit our website at www.kasikornbank.com 1 KASIKORNBANK at a Glance Established on June 8, 1945 with registered capital of Bt5mn (USD0.15mn) Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) since 1976 Consolidated (as September of 2018) Assets Bt3,054bn (USD94.3bn) Ranked #4 with 15.2% market share** Loans* Bt1,849bn (USD57.1bn) Ranked #4 with 15.0% market share** Deposits Bt1,921bn (USD59.3bn) Ranked #4 with 15.6% market share** CAR 18.96% *** ROE (9M18) 11.65% ROA (9M18) 1.41% Number of Branches 1,000 Number of ATMs 9,228 Number of K PLUS Users 9.4mn Number of Employees 20,599 Share Information SET Symbol KBANK, KBANK-F Share Capital: Authorized Bt30.5bn (USD0.9bn) Issued and Paid-up Bt23.9bn (USD0.7bn) Number of Shares 2.4bn shares Market Capitalization Bt464bn (USD14.0bn) Ranked #1 in Thai banking sector 3Q18 Avg. Share Price: KBANK Bt209.55 (USD6.47) KBANK-F Bt212.57 (USD6.56) EPS (9M18) Bt13.13 (USD0.41) BVPS Bt154.82 (USD4.78) Notes: * Loans = Loans to customers less deferred revenue ** Assets, loans and deposits market share is based on C.B.1.1 (Monthly statement of assets and liabilities) of 14 Thai commercial banks as of September 2018 *** Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) has been reported in accordance with Basel III Capital Requirement from 1 January 2013 onwards. CAR is based on KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE. KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE means the company under the Notification of the Bank of Thailand re: Consolidated Supervision, consisted of KBank, K Companies and subsidiaries operating in supporting KBank, Phethai Asset Management Co., Ltd. -

Three Essays in Banking Sector of Thailand A

THREE ESSAYS IN BANKING SECTOR OF THAILAND A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Itthipong Mahathanaseth August 2011 © 2011 Itthipong Mahathanaseth THREE ESSAYS IN BANKING SECTOR OF THAILAND Itthipong Mahathanaseth, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation consists of three essays. The first essay examines the cost efficiency and production technology in the banking sector of Thailand using a stochastic frontier approach. The empirical results indicate that banks with lower Non-performing-loan- to-total-loan ratio, higher equity-to-total-asset ratio, higher liquid-asset-to-total-asset ratio, and more branches are likely to be more efficient. The second essay investigates the degree of competition in the banking industry using the new empirical industrial organization approach. The empirical results indicate that, despite the Thailand government’s efforts to increase competition in the banking industry by relaxing restrictions on entry to the market after the financial crisis, the oligopolistic degree of the biggest four banks has intensified. The third essay links the results of the first and second essays, cost efficiency and competition in the banking sector, to the transmission mechanism of monetary policy in Thailand using Vector Autoregression approach. The empirical results indicate that an unexpected tightening monetary policy shock leads to higher financial costs in the banking industry, forcing banks to compete more fiercely and operate more efficiently, significantly helping strengthen the transmission of monetary policy. Hence, the policy implication is that Thai government should exert more effort to enhance efficiency and competition in the banking sector. -

KTB: Krung Thai Bank Public Company Limited | Annual Report

A N U L R E P O T 2 0 1 3 K r u n g h a i B k c l . TRANS FORMA TION 35 Sukhumvit Road, Klong Toey Nua Subdistrict, Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Tel : +662 255-2222 Fax : +662 255-9391-3 KTB Call Center : 1551 Swift : KRTHTHBK http://www.ktb.co.th Annual Report 2013 K T B T r a n s f o r m a t i o n This annual report uses Green Read paper for low-eye strain and is printed with soybean ink that reduces carbon dioxide emission and has light weight for less energy consumed in delivery. Produced by : Business Risk Research Department Risk Management Sector Risk Management Group Krung Thai Bank Pcl. Designed by : Work Actually Co., Ltd. Printed by : Plan Printing Co., Ltd. Transformation…for a Sustainable Growth KTB has transformed its internal operation process and improve people capability for greater efficiency in customer services and business expansion under accurate and efficient risk management that will lead to enhanced competitiveness and readiness to make a sustainable leap together with customers, society, shareholders and stakeholders. K T B T r a n s f o r m a t i o n KTB e-Certificate ของ่าย ได้เร็ว ขอหนังสือรับรอง นิติบุคคล การประกอบธุรกิจ คนต่างด้าว สมาคมและหอการค้า 4 KTB สินเชื่อ SME เพื่อรับงานภาครัฐ หนังสือคํ้าประกันทันใจ แค่ 1 วัน Net Free Zero รับได้เลย จาก KTB netbank แบบอั้นๆ หลบไปเลย....Net Free Zero ค่าธรรมเนียม ฟรี ไม่มีอั้น ตัวจริง! มาแล้ว Annual Report 2013 Krung Thai Bank Pcl. สินเชื่อกรุงไทย 3 สบาย สินเชื่อบุคคล ที่ ให้ ชีวิต มีแต่เรื่อง สบายๆ บริการโอนเงินต่างประเทศ มุมไหนใน โลก ก็ โอนถึง ใน 1 วัน 5 สินเชื่ออเนกประสงค์ -

Investor Presentation As of 4Q20

KASIKORNBANK Investor Presentation as of 4Q20 January 2021 For further information, please contact the Investor Relations Unit or visit our website at www.kasikornbank.com 1 KASIKORNBANK at a Glance Established on June 8, 1945 with registered capital of Bt5mn (USD0.17mn) Listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) since 1976 Consolidated (as of December 2020) Assets Bt3,659bn (USD121.8bn) Ranked #4 with 15.5% market share** Loans* Bt2,245bn (USD74.7bn) Ranked #3 with 16.4% market share** Deposits Bt2,345bn (USD78.1bn) Ranked #4 with 16.2% market share** CAR 18.80% *** ROE 7.10% **** ROA 0.85% Number of Branches 860 Number of E-Machine (ATM/RCM) 10,981 Number of K PLUS Users 14.4mn Number of Employees 19,862 Share Information SET Symbol KBANK, KBANK-F Share Capital: Authorized Bt30.2bn (USD1.0bn) Issued and Paid-up Bt23.7bn (USD0.8bn) Number of Shares 2.4bn shares Market Capitalization Bt268n (USD8.9bn) Ranked #2 in Thai banking sector 4Q20 Avg. Share Price: KBANK Bt94.89 (USD3.16) KBANK-F Bt95.10 (USD3.17) EPS Bt5.60 (USD0.19) BVPS Bt179.00 (USD5.96) Notes: * Loans = Loans to customers less deferred revenue ** Assets, loans and deposits market share is based on C.B.1.1 (Monthly statement of assets and liabilities) of 14 Thai commercial banks as of December 2020 *** Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) has been reported in accordance with Basel III Capital Requirement from 1 January 2013 onwards. CAR is based on KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE. KASIKORNBANK FINANCIAL CONGLOMERATE means the company under the Notification of the Bank of Thailand re: Consolidated Supervision, consisted of KBank, K Companies and subsidiaries operating in supporting KBank, Phethai Asset Management Co., Ltd. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report Financial Consumer Protection Assessment Report

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Financial Consumer Protection Assessment Report Kingdom of Thailand: TA7998 (THA) - Development of a Strategic Framework for Financial Inclusion in Thailand (Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction) October 2013 Prepared by: Robert Hickson and Patamawadee Suzuki Microfinance Services Pty Ltd Gold Coast, Australia For: Fiscal Policy Office Bureau of Financial Inclusion Development Policy This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS US$1.00 = THB 31.36 ABBREVIATIONS A2II Access to Insurance Initiative POS (electronic) Points of Sale ADB Asian Development Bank BIS Bank for International Settlements BAAC Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives BOT Bank of Thailand FIPD Bureau of Financial Inclusion Policy and Development CBFI Community Based Financial Institution CBFI Community Based Financial Institution CBO Community Based Organization CDD Community Development Department (MOI) CODI Community Organizations Development Institute CPD Cooperative Promotion Department (Min. Agriculture & Coops) CAD Cooperatives Audit Department (Min. Agriculture & Cooperatives) CULT Credit Union League of Thailand DPA Deposit Protection Agency Act EA Executing Agency (of Government) FCP Foundation for Consumer Protection FIBA Financial Institutions Business Ac FIDF Financial Institutions Development Fund FSMP Financial Sector Master Plan FPO Fiscal Policy Office