FC-Austria.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Austria FULL Constitution

AUSTRIA THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF 1920 as amended in 1929 as to Law No. 153/2004, December 30, 2004 Table of Contents CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union CHAPTER II Legislation of the Federation CHAPTER III Federal Execution CHAPTER IV Legislation and Execution by the Länder CHAPTER V Control of Accounts and Financial Management CHAPTER VI Constitutional and Administrative Guarantees CHAPTER VII The Office of the People’s Attorney ( Volksanwaltschaft ) CHAPTER VIII Final Provisions CHAPTER I General Provisions European Union A. General Provisions Article 1 Austria is a democratic republic. Its law emanates from the people. Article 2 (1) Austria is a Federal State. (2) The Federal State is constituted from independent Länder : Burgenland, Carinthia, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tirol, Vorarlberg and Vienna. Article 3 (1) The Federal territory comprises the territories ( Gebiete ) of the Federal Länder . (2) A change of the Federal territory, which is at the same time a change of a Land territory (Landesgebiet ), just as the change of a Land boundary inside the Federal territory, can—apart from peace treaties—take place only from harmonizing constitutional laws of the Federation (Bund ) and the Land , whose territory experiences change. Article 4 (1) The Federal territory forms a unitary currency, economic and customs area. (2) Internal customs borders ( Zwischenzollinien ) or other traffic restrictions may not be established within the Federation. Article 5 (1) The Federal Capital and the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation is Vienna. (2) For the duration of extraordinary circumstances the Federal President, on the petition of the Federal Government, may move the seat of the supreme bodies of the Federation to another location in the Federal territory. -

Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective

CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.), Williamson (Guest Ed.) • 1914: Aus tria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I War of World the Origins, and First Year tria-Hungary, Austrian Federalism in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof AustrianFerdinand Federalism Karlhofer (Eds.) in Comparative Perspective Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Federalism in ŽŵƉĂƌĂƟǀĞWĞƌƐƉĞĐƟǀĞ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 24 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2015 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70148, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Book design by Allison Reu and Alex Dimeff Cover photo © Parlamentsdirektion Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011124 ISBN: 9783902936691 UNO PRESS Publication of this volume has been made possible through generous grants from the the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration, and Foreign Affairs in Vienna through the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York, as well as the Federal Ministry of Economics, Science, and Research through the Austrian Academic Exchange Service (ÖAAD). The Austrian Marshall Plan Anniversary Foundation in Vienna has been very generous in supporting Center Austria: The Austrian Marshall Plan Center for European Studies at the University of New Orleans and its publications series. -

Chapter 8 the Interface Between Subnational and National Levels Of

8. THE INTERFACE BETWEEN SUBNATIONAL AND NATIONAL LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT – 143 Chapter 8 The interface between subnational and national levels of government Multilevel regulatory governance – that is to say, taking into account the rule-making and rule-enforcement activities of all the different levels of government, not just the national level – is another core element of effective regulatory management. The OECD’s 2005 Guiding Principles for Regulatory Quality and Performance “encourage Better Regulation at all levels of government, improved co-ordination, and the avoidance of overlapping responsibilities among regulatory authorities and levels of government”. It is relevant to all countries that are seeking to improve their regulatory management, whether they are federations, unitary states or somewhere in between. In many countries local governments are entrusted with a large number of complex tasks, covering important parts of the welfare system and public services such as social services, health care and education, as well as housing, planning and building issues, and environmental protection. Licensing can be a key activity at this level. These issues have a direct impact on the welfare of businesses and citizens. Local governments within the boundaries of a state need increasing flexibility to meet economic, social and environmental goals in their particular geographical and cultural setting. At the same time, they may be taking on a growing responsibility for the implementation of EC regulations. All of this requires a pro active consideration of: • The allocation/sharing of regulatory responsibilities at the different levels of government (which can be primary rule-making responsibilities; secondary rule-making responsibilities based on primary legislation, or the transposition of EC regulations; responsibilities for supervision/enforcement of national or subnational regulations; or responsibilities for service delivery). -

European Rule of Law Mechanism

European Rule of Law Mechanism Austrian Input European Rule of Law Mechanism Austrian Input Vienna, May 2020 Imprint Austrian Federal Chancellery Ballhausplatz 2, 1010 Vienna +43 1 531 15-0 [email protected] bundeskanzleramt.gv.at Design: BKA Design & Grafik Vienna, 2020 Contents Introduction 5 I Justice System 7 A Independence 8 B Quality of justice 15 C Efficiency of the justice system 18 II Anti-corruption framework 25 A The institutional framework capacity to fight against corruption (prevention and investigation / prosecution) 25 B Prevention 28 C Repressive measures 37 III Media Pluralism 42 A Media regulatory authorities and bodies 43 B Transparency of media ownership and government interference 45 C Framework for journalists’ protection 47 IV Other institutional issues related to checks and balances 50 A The process for preparing and enacting laws 50 B Independent authorities 53 C Accessibility and judicial review of administrative decisions 58 D The enabling framework for civil society 61 Introduction Respect for the rule of law in the Member States and the Union is an important foun- dation for the cooperation within the EU. There can be no compromises on European fundamental values. In its 2020–2024 programme, the Austrian Federal Government emphasises the importance of respecting fundamental European values, advocates strengthening the instruments for safeguarding the rule of law at European level and provides for a number of initiatives at national level. Austria strongly supports the new Rule of Law Cycle proposed by the European Commis- sion in July 2019 and considers the regular and systematic review of all Member States to be an essential step towards strengthening the rule of law. -

The Provisional Government of Austria

RICE UNIVERSITY THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF AUSTRIA April 27 to December 12. ®y Mary Ann Pro bus Anzelmo A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Thesis Director's Signature: Houston, Texas May, 1968 ABSTRACT THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OP AUSTRIA April 27 to December 13* 19^5 Mary Arm Probus Anzelmo Austria's future in the closing days of World War II was uncertain. The Allies had expected to find a political vacuum. Yet, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, an Austrian provisional government emerged from • the postwar rubble within one-month after Allied liber¬ ation. This study examines the atmosphere which made pos¬ sible such a rapid congealing of political forces, the . initial formation of the government, the difficulties presented by the Soviets on the one hand and the western powers on the other, and the many factors which enabled the government to overcome these difficulties. The importance of the provisional government has frequently been underestimated. For its success in lay¬ ing the foundation for viable Austrian independence, it deserves more credit than its achievements as an interim government suggest. DEDICATION This study I dedicate to those two who have always mattered most:- Sam and Margaret PREFACE The creation of the Austrian Provisional Government in the fascinating milieu, of post World War II Vienna has occupied my interests for the last two years. In the story of the evolution of this interim governmental agency per¬ haps lies the key to Austria’s emergence as an independent nation--free from the domination of any power, east or west. -

PDF-Dokument

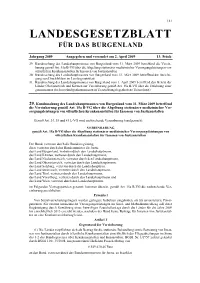

141 LANDESGESETZBLATT FÜR DAS BURGENLAND Jahrgang 2009 Ausgegeben und versendet am 2. April 2009 13. Stück 29. Kundmachung des Landeshauptmannes von Burgenland vom 31. März 2009 betreffend die Verein- barung gemäß Art. 15a B-VG über die Abgeltung stationärer medizinischer Versorgungsleistungen von öffentlichen Krankenanstalten für Insassen von Justizanstalten 30. Kundmachung des Landeshauptmannes von Burgenland vom 31. März 2009 betreffend die Berichti- gung von Druckfehlern im Landesgesetzblatt 31. Kundmachung des Landeshauptmannes von Burgenland vom 1. April 2009 betreffend den Beitritt der Länder Oberösterreich und Kärnten zur Vereinbarung gemäß Art. 15a B-VG über die Errichtung einer gemeinsamen Sachverständigenkommission in Tierzuchtangelegenheiten (Tierzuchtrat) 29. Kundmachung des Landeshauptmannes von Burgenland vom 31. März 2009 betreffend die Vereinbarung gemäß Art. 15a B-VG über die Abgeltung stationärer medizinischer Ver- sorgungsleistungen von öffentlichen Krankenanstalten für Insassen von Justizanstalten Gemäß Art. 34, 35 und 81 L-VG wird nachstehende Vereinbarung kundgemacht: VEREINBARUNG gemäß Art. 15a B-VG über die Abgeltung stationärer medizinischer Versorgungsleistungen von öffentlichen Krankenanstalten für Insassen von Justizanstalten Der Bund, vertreten durch die Bundesregierung, diese vertreten durch den Bundesminister für Justiz, das Land Burgenland, vertreten durch den Landeshauptmann, das Land Kärnten, vertreten durch den Landeshauptmann, das Land Niederösterreich, vertreten durch den Landeshauptmann, das Land -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) CJEU (Case C-208/09: Ilonka Sayn-Wittgenstein v Landeshauptmann von Wien: respecting constitutional identity in the EU) Besselink, L.F.M. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Published in Common Market Law Review Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Besselink, L. F. M. (2012). CJEU (Case C-208/09: Ilonka Sayn-Wittgenstein v Landeshauptmann von Wien: respecting constitutional identity in the EU). Case note on: CJEU, 22/12/10 Common Market Law Review, 2012(2), 671-693. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 COMMON MARKET LAW REVIEW CONTENTS Vol. 49 No. 2 April 2012 Editorial comments, Fundamental rights and EU membership: Do as I say, not as I do! 481–488 Articles A. -

Self-Determination Along the Austrian Frontier, 1918-1920: Case Studies of German Bohemia, Vorarlberg, and Carinthia

Self-Determination along the Austrian Frontier, 1918-1920: Case Studies of German Bohemia, Vorarlberg, and Carinthia Matthew Vink A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Victoria University of Wellington 2013 ii Abstract The First World War led to the collapse of a number of prominent European empires, allowing for the spread of new ideas into Europe. US President Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric of national self-determination attracted particular symbolic importance because it legitimised popular sovereignty through the use of plebiscites. German-Austrians, like other national groups within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, used self-determination to justify establishing independent successor states after the war. The German-Austrian Republic, founded in 1918, claimed all German-speaking regions of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire on the basis of self- determination. This thesis examines claims to self-determination in three different cases: German Bohemia, Vorarlberg, and Carinthia. Representatives from each region took their case to the Paris Peace Conference, appealing to the Allied delegations to grant international recognition. These representatives faced much opposition, both from local non-German populations and occasionally even from the German-Austrian government itself. German-Austrian politicians in the Czech lands opposed the incorporation of German- majority lands into Czechoslovakia, and instead sought to establish an autonomous German Bohemian province as part of German-Austria. In Paris, Allied delegations supported the historic frontier of the Czech lands, and therefore opposed local German self-determination outright, refusing demands for a plebiscite in German Bohemia. Vorarlberg representatives sought Vorarlberg’s secession from German-Austria, hoping instead for union with Switzerland. -

The Results of the Edict of Toleration in the Southern Austrian Province of Carinthia During the Reign of Joseph II

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 The Results of the Edict of Toleration in the Southern Austrian Province of Carinthia During the Reign of Joseph II. Barry Royce Barlow Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Barlow, Barry Royce, "The Results of the Edict of Toleration in the Southern Austrian Province of Carinthia During the Reign of Joseph II." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4895. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4895 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Law, Time, and Sovereignty in Central Europe: Imperial Constitutions, Historical Rights, and the Afterlives of Empire

Law, Time, and Sovereignty in Central Europe: Imperial Constitutions, Historical Rights, and the Afterlives of Empire Natasha Wheatley Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Natasha Wheatley All rights reserved ABSTRACT Law, Time, and Sovereignty in Central Europe: Imperial Constitutions, Historical Rights, and the Afterlives of Empire Natasha Wheatley This dissertation is a study of the codification of empire and its unexpected consequences. It returns to the constitutional history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire — a subject whose heyday had passed by the late 1920s — to offer a new history of sovereignty in Central Europe. It argues that the imperatives of imperial constitutionalism spurred the creation a rich jurisprudence on the death, birth, and survival of states; and that this jurisprudence, in turn, outlived the imperial context of its formation and shaped the “new international order” in interwar Central Europe. “Law, Time, and Sovereignty” documents how contemporaries “thought themselves through” the transition from a dynastic Europe of two-bodied emperor-kings to the world of the League of Nations. The project of writing an imperial constitution, triggered by the revolutions of 1848, forced jurists, politicians and others to articulate the genesis, logic, and evolution of imperial rule, generating in the process a bank or archive of imperial self-knowledge. Searching for the right language to describe imperial sovereignty entailed the creative translation of the structures and relationships of medieval composite monarchy into the conceptual molds of nineteenth-century legal thought. While the empire’s constituent principalities (especially Hungary and Bohemia) theoretically possessed autonomy, centuries of slow centralization from Vienna had rendered that legal independence immaterial. -

Monitoring of the European Charter of Local Self-Government in Austria

STATUTORY FORUM Report CG-FORUM(2020)01-03final 28 September 2020 Monitoring of the European Charter of Local Self-Government in Austria Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the European Charter of Local Self-Government (Monitoring Committee) Rapporteurs:1 Marc COOLS, Belgium (L, ILDG) Andrew DISMORE, United-Kingdom (R, SOC/G/PD) Recommendation 446 (2020) ........................................................................................................................ 2 Explanatory memorandum ............................................................................................................................ 5 Summary This report was prepared following the second monitoring visit to Austria since the country ratified the Charter in 1987. It welcomes the constitutional and legal recognition and substantial implementation of the principle of local self-government in Austria, the introduction of the Länder Administrative Courts to strengthen Austrian federalism, the extension of the competences of the associations of local authorities to co-operate and the reforms carried out since 2011 with a view to clarifying the distribution of competences between the Federation, the Länder and local authorities. The adoption of the New Government Plan with the objective, among other things, to tackle some of the outstanding issues reflected in this report has also been welcomed. At the same time, the rapporteurs stress that in Austria there is still a high degree of complexity in the allocation of -

Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Directorate for Education Education and Training Policy Division Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers Country Note: Austria Françoise Delannoy, Phillip McKenzie, Stefan Wolter and Ben van der Ree1 This report is based on a study visit to Austria in April-May 2003, and background documents prepared to support the visit. A draft report was sent to Austria for feedback in November 2003. Following the receipt of feedback in April 2004, minor revisions were made to the draft. The report is based on the situation in Austria up to the period April – May 2003. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Austria, the OECD or its Member countries. 1. Ben van der Ree died on 29 June, 2003. He made substantial contributions to the work during the Austrian visit and in preparing drafts for this report. He was a fine educator and a valued team member, and he is deeply missed. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purposes of the OECD Review ........................................................................................................ 4 1.2 The Participation of Austria ............................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Structure of the Country Note .........................................................................................................