The Ecology of Dry River Beds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Assessment of Agricultural Potential of Soils in the Gulf Region, North Queensland

REPORT TO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES REGIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT (RID), NORTH REGION ON An Assessment of Agricultural Potential of Soils in the Gulf Region, North Queensland Volume 1 February 1999 Peter Wilson (Land Resource Officer, Land Information Management) Seonaid Philip (Senior GIS Technician) Department of Natural Resources Resource Management GIS Unit Centre for Tropical Agriculture 28 Peters Street, Mareeba Queensland 4880 DNRQ990076 Queensland Government Technical Report This report is intended to provide information only on the subject under review. There are limitations inherent in land resource studies, such as accuracy in relation to map scale and assumptions regarding socio-economic factors for land evaluation. Before acting on the information conveyed in this report, readers should ensure that they have received adequate professional information and advice specific to their enquiry. While all care has been taken in the preparation of this report neither the Queensland Government nor its officers or staff accepts any responsibility for any loss or damage that may result from any inaccuracy or omission in the information contained herein. © State of Queensland 1999 For information about this report contact [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors thank the input of staff of the Department of Natural Resources GIS Unit Mareeba. Also that of DNR water resources staff, particularly Mr Jeff Benjamin. Mr Steve Ockerby, Queensland Department of Primary Industries provided invaluable expertise and advice for the development of the agricultural suitability assessment. Mr Phil Bierwirth of the Australian Geological Survey Organisation (AGSO) provided an introduction to and knowledge of Airborne Gamma Spectrometry. Assistance with the interpretation of AGS data was provided through the Department of Natural Resources Enhanced Resource Assessment project. -

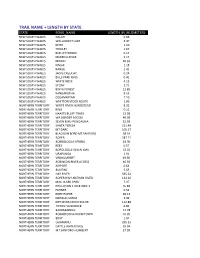

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

When the River Runs Dry: Human and Ecological Values of Dry Riverbeds

CONCEPTS AND QUESTIONS 202 When the river runs dry: human and ecological values of dry riverbeds Alisha L Steward1,2*, Daniel von Schiller3, Klement Tockner4, Jonathan C Marshall1, and Stuart E Bunn2 Temporary rivers and streams that naturally cease to flow and dry up can be found on every continent. Many other water courses that were once perennial now also have temporary flow regimes due to the effects of water extraction for human use or as a result of changes in land use and climate. The dry beds of these temporary rivers are an integral part of river landscapes. We discuss their importance in human culture and their unique diversity of aquatic, amphibious, and terrestrial biota. We also describe their role as seed and egg banks for aquatic biota, as dispersal corridors and temporal ecotones linking wet and dry phases, and as sites for the storage and processing of organic matter and nutrients. In light of these valuable functions, dry riverbeds need to be fully integrated into river management policies and monitoring programs. We also identify key knowledge gaps and suggest research questions concerning the values of dry riverbeds. Front Ecol Environ 2012; 10(4): 202–209, doi:10.1890/110136 (published online 29 Mar 2012) ivers that intermittently cease to flow and “run dry” mobilize, deposit, and scour bed sediments. They can also R have been described as being more representative of be exposed to intense solar radiation, wind, and extreme the world’s river systems than those with perennial flows temperatures (Steward et al. 2011). Dry riverbeds may be (Williams 1988). -

Into Queensland, to Within 45 Km of the Georgina River Floodout Complex

into Queensland, to within 45 km of the Georgina River floodout complex. As a consequence, it is correctly included in the Georgina Basin. There is one river of moderate size in the Georgina basin that does not connect to any of the major rivers and that is Lucy Creek, which runs east from the Dulcie Ranges and may once have connected to the Georgina via Manners Creek. Table 7. Summary statistics of the major rivers and creeks in Lake Eyre Drainage Division Drainage Major Tributaries Initial Interim Highest Point Height of Lowest Straight System Bioregion & in Catchment highest Point Line Terminal (m asl) Major in NT Length Bioregions Channel (m asl) (km) (m asl) Finke River Basin: Finke R. Hugh R., Palmer R., MAC FIN, STP, 1,389 700 130 450† Karinga Ck., SSD Mt Giles Coglin Ck. Todd River Basin: Todd R. Ross R. BRT MAC, SSD 1,164 625 220 200 Mt Laughlin Hale R. Cleary Ck., Pulya Ck. MAC SSD 1,203 660 200 225 Mt Brassey Illogwa Ck. Albarta Ck. MAC BRT, SSD 853 500 230 140 Mt Ruby Hay River Basin: Plenty R. Huckitta Ck., Atula MAC BRT, SSD 1,203 600 130 270 Ck., Marshall R. Mt Brassey Corkwood (+ Hay R.) Bore Hay R. Marshall R., Arthur MAC, BRT, SSD 594 440 Marshal 70 355 Ck. (+ Plenty R.) CHC 340 Arthur Georgina River Basin: Georgina R. Ranken R., James R., MGD, CHC, SSD 220 215 190 >215 † (?Sandover R.) (?BRT) Sandover R. Mueller Ck., Waite MAC, BRT, BRT, 996 550 260 270 Ck., Bundey R., CHC, DAV CHC, Bold Hill Ooratippra Ck. -

IR 519 Preliminary Analysis of Streamflow Characteristics of The

internal report 519 Preliminary analysis of streamflow characteristics of the tropical rivers region DR Moliere February 2007 (Release status - unrestricted) Preliminary analysis of streamflow characteristics of the tropical rivers region DR Moliere Hydrological and Geomorphic Processes Program Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist Supervising Scientist Division GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 February 2007 Registry File SG2006/0061 (Release status – unrestricted) How to cite this report: Moliere DR 2007. Preliminary analysis of streamflow characteristics of the tropical rivers region. Internal Report 519, February, Supervising Scientist, Darwin. Unpublished paper. Location of final PDF file in SSD Explorer \Publications Work\Publications and other productions\Internal Reports (IRs)\Nos 500 to 599\IR519_TRR Hydrology (Moliere)\IR519_TRR hydrology (Moliere).pdf Contents Executive summary v Acknowledgements v Glossary vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Climate 2 2 Hydrology 5 2.1 Annual flow 5 2.2 Monthly flow 7 2.3 Focus catchments 11 2.3.1 Data 11 2.3.2 Data quality 18 3 Streamflow classification 19 3.1 Derivation of variables 19 3.2 Multivariate analysis 24 3.2.1 Effect of flow data quality on hydrology variables 31 3.3 Validation 33 4 Conclusions and recommendations 35 5 References 35 Appendix A – Rainfall and flow gauging stations within the focus catchments 38 Appendix B – Long-term flow stations throughout the tropical rivers region 43 Appendix C – Extension of flow record at G8140040 48 Appendix D – Annual runoff volume and annual peak discharge 52 Appendix E – Derivation of Colwell parameter values 81 iii iv Executive summary The Tropical Rivers Inventory and Assessment Project is aiming to categorise the ecological character of rivers throughout Australia’s wet-dry tropical rivers region. -

Regional Flood Methods Database Used to Develop ARR RFFE Technique

Australian Rainfall & Runoff Revision Projects PROJECT 5 Regional Flood Methods Database Used to Develop ARR RFFE Technique STAGE 3 REPORT P5/S3/026 MARCH 2015 Engineers Australia Engineering House 11 National Circuit Barton ACT 2600 Tel: (02) 6270 6528 Fax: (02) 6273 2358 Email:[email protected] Web: http://www.arr.org.au/ AUSTRALIAN RAINFALL AND RUNOFF PROJECT 5: REGIONAL FLOOD METHODS: DATABASE USED TO DEVELOP ARR RFFE TECHNIQUE 2015 MARCH, 2015 Project ARR Report Number Project 5: Regional Flood Methods: Database used to develop P5/S3/026 ARR RFFE Technique 2015 Date ISBN 4 March 2015 978-0-85825-940-9 Contractor Contractor Reference Number University of Western Sydney 20721.64138 Authors Verified by Ataur Rahman Khaled Haddad Ayesha S Rahman Md Mahmudul Haque Project 5: Regional Flood Methods ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was made possible by funding from the Federal Government through Geoscience Australia. This report and the associated project are the result of a significant amount of in kind hours provided by Engineers Australia Members. Contractor Details The University of Western Sydney School of Computing, Engineering and Mathematics, Building XB, Kingswood Locked Bag 1797, Penrith South DC, NSW 2751, Australia Tel: (02) 4736 0145 Fax: (02) 4736 0833 Email: [email protected] Web: www.uws.edu.au P5/S3/026 : 4 March 2015 ii Project 5: Regional Flood Methods FOREWORD ARR Revision Process Since its first publication in 1958, Australian Rainfall and Runoff (ARR) has remained one of the most influential and widely used guidelines published by Engineers Australia (EA). The current edition, published in 1987, retained the same level of national and international acclaim as its predecessors. -

Trail Location by Postcode

TRAIL LOCATION BY POSTCODE STATE POSTCODE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NORTHERN TERRITORY 0822 NUMBULWAR 9 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 1 135 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 80 0 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BAKER 2 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BALAMURRA 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BARRABARRAC 36 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BASEDOW 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BATTEN 5 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BAWUDA 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFO 77 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BLYTH 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BOROLOOLA‐CALVERT H96 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 30 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BOROLOOLA‐SPRING CR 122 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BORROLOOLA‐CALVERT HILL 38 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 128 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BRAY 2 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BROAD ARROW 43 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BUCHANAN 0 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BULLITA‐TIMBER 92 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BUNDEY 2 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 BUNTINE 11 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 DOWNER 2 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 DRY RIVER STOCK ROUTE 226 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 ELSEY 5 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 FURNER 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 GIBBIE CREEK 63 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 GORRIE‐DRY 329 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 HODGSON RIVER 120 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 HOME 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 HOOKER CK‐TANAMI MI 48 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 HOOKER CREEK‐TANAMI 41 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 HOWE 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 HUMBERT 136 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 JAMUNBUK 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 KING 1 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 LAJAMANU 162 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 MOROAK 36 NORTHERN TERRITORY 0852 MT SANFORD‐HUMBERT 116 NORTHERN -

Freshwater Fishes of the Burdekin Dry Tropics Acknowledgements

Freshwater Fishes of the Burdekin Dry Tropics Acknowledgements Much of the information about fish species and their distribution in the Burdekin Dry Tropics NRM region is based on the work of Dr Brad Pusey (Griffith University). The Australian Centre for Tropical Freshwater Research (ACTFR) provided access to their Northern Australian Fish (NAF) database which contains the most current fish survey data for tropical Australia. Dr Allan Webb (ACTFR) provided information on the exotic fish species recorded from the immediate Townsville region. Thanks to Alf Hogan from Fisheries Queensland for providing data on species distribution. Thanks also to Bernard Yau and efishalbum for their image of the Threadfin Silver Biddy. Published by NQ Dry Tropics Ltd trading as NQ Dry Tropics. Copyright 2010 NQ Dry Tropics Ltd ISBN 978-921584-21-3 The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study research, news reporting, criticism, or review. Selected passages, tables or diagrams may be reproduced for such purposes provided acknowledgement of the source is included. Major extracts of the entire document may not be reproduced by any process without the written permission of the Chief Executive Officer, NQ Dry Tropics. Please reference as: Carter, J & Tait, J 2010, Freshwater Fishes of the Burdekin Dry Tropics, Townsville. Further copies may be obtained from NQ Dry Tropics or from our Website: www.nqdrytropics.com.au Cnr McIlwraith and Dean St P.O Box 1466, Townsville Q 4810 Ph: (07) 4724 3544 Fax: (07) 4724 3577 Important Disclaimer: The information contained in this report has been compiled in good faith from sources NQ Dry Tropics Limited trading as NQ Dry Tropics believes to be reliable. -

Western Queensland

Western Queensland - Gulf Plains, Northwest Highlands, Mitchell Grass Downs and Channel Country Bioregions Strategic Offset Investment Corridors Methodology Report April 2016 Prepared by: Strategic Environmental Programs/Conservation and Sustainability Services, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. -

NT Learning Adventures Guide

NT Learning Adventures NT Learning Adventures | 1 Save & Learn in the NT Tourism NT recognises that costs and timing are major factors when planning an excursion for your students. The NTLA Save & Learn program provides funding to interstate schools to help with excursion costs - making it easier to choose an NT Learning Adventure for your next school trip. The NT welcomes school groups year round! Go to ntlearningadventures.com to see the current terms and conditions of the NTLA Save & Learn program. Kakadu Darwin Arnhem Land Katherine Tennant Creek For more information and to download Alice Springs a registration form visit: W ntlearningadventures.com Uluru E [email protected] T 08 8951 6415 Uluru Icon made by Freepik. www.flaticon.com is licensed under Creative Commons BY 3.0 2 | NT Learning Adventures Contents Disclaimer This booklet has been produced by Tourism NT NT Learning Adventures 2 to promote the Northern Territory (NT) as an educational tourism destination, in the service of the community and on behalf of the educational Suggested Itineraries 4 tourism sector, to encourage school group visitation to the region. Tour & Travel Operators 12 The material contained in this booklet provides general information, for use as a guide only. It is not Alice Springs Region 27 intended to provide advice and should not be relied upon as such. You should make further enquires and seek independent advice about the appropriateness Learning Adventures 28 of each experience for your particular needs and to inform your travel decisions. Accommodation 36 Climatic conditions and other environmental factors in the NT may impact on travel plans and a person’s ability to engage in activities. -

COAG National Bushfire Inquiry

Appendix D Fire history in Australia This appendix summarises the available information on major bushfire events in each state and territory as far back as records allow. There are many inconsistencies and gaps in the available information because there are no nationally agreed criteria for defining a ‘significant fire year’ or a ‘major fire event’. The available information shows the following: • Major fire events are a periodic feature in all states and territories. • The areas of land that are affected by fire continue to be significant. • There have been 59 recorded bushfire events where there has been loss of life, with a positive trend being the significant decline in the loss of life from bushfires in the last 20 years. • There have been 24 fire events resulting in major stock losses (defined as more than 1000 head). • There have been 21 fire events resulting in large-scale loss of houses (defined as more than 50 houses). Table D.1 Fire history in Australia, by state and territory No. of Area of fire Date deaths (ha) Losses Location(s) Northern Territory 1968–1969 40 000 000 Killarney – Top Springs 1969–1970 45 000 000 Dry River – Victoria River fire 1974–1975 45 000 000 Barkly Tableland, Victoria River district, near Newcastle Waters 2002 38 000 000 Queensland 1917 3 Large fires near Hughenden, followed by a fire on Warenda Station 1918 October 2 >100 000 sheep Fires spread over a huge area from Charleville to Blackall, Barcaldine, Hughenden 1918 October 5 Saltern Creek 1926 Forests, farms, sugar South-east corner of Queensland -

Alice Springs Telegraph Station Fact Sheet And

Alice Springs Telegraph Station Historical Reserve The Alice Springs Telegraph Station An entry fee, which includes a Historical Reserve marks the self-guided tour map, is payable Safety and Comfort original site of the first European for access to the buildings in the • Observe park safety signs. settlement in Alice Springs. Historical Precinct (free for locals). • Carry and drink plenty of water. Established in 1872 to relay Access to the remainder of the • Wear a shady hat (or helmet if cycling), sunscreen, insect messages between Darwin and Reserve is free. repellent, suitable clothing and Adelaide, it is the best preserved When to visit footwear. of the twelve stations along the The Reserve is accessible all year • Avoid strenuous activity during Fact Sheet Overland Telegraph Line. The site round. The cooler months (April to the heat of the day. was first recorded by surveyor September) are the most pleasant. • Consider your health and fitness William Mills in March 1871, who when choosing a walk or ride. The Reserve is open between 8am was in search of a suitable route Please Remember and 9pm every day of the year. for the Overland Telegraph Line • Keep to designated roads and through the MacDonnell Ranges. The Historical Precinct is open tracks. Construction of the Telegraph 9am - 5pm every day except • All historic, cultural items and Station began in November 1871. Christmas Day. wildlife are protected. • Use the barbecues provided. The township of Alice Springs What to do obtained its name from the • Put your rubbish in the bins Picnicking - The shaded provided or take it with you.