How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guarani and Kaiowá Peoples' Human Right to Adequate Food And

THE GUARANI AND KAIOWÁ PEOPLES’ HUMAN RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD AND NUTRITION NUTRITION FOOD AND ADEQUATE HUMAN RIGHTTO AND KAIOWÁPEOPLES’ THE GUARANI A A HOLISTIC APPROACH THE GUARANI AND KAIOWÁ PEOPLES’ HUMAN RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD AND NUTRITION A HOLISTIC APPROACH | Executive Summary Executive Summary Executive MISSIONARY COUNCIL FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES THE GUARANI AND KAIOWÁ PEOPLES’ HUMAN RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD AND NUTRITION A HOLISTIC APPROACH | Executive Summary Support: This Executive Summary is a publication of FIAN Brazil, with FIAN International and the Conselho Indigenista Missionário (CIMI): Missionary Council of Indig- enous Peoples, with support from HEKS/EPER, Brot für die Welt and Misereor. Author Photography Thaís Franceschini Ruy Sposati/CIMI Alex del Rey/FIAN International Revision Valéria Burity/FIAN Brazil Valéria Burity Flavio Valente Graphic Design Angélica Castañeda Flores www.boibumbadesign.com.br Felipe Bley Folly Lucas Prates This document is based on “The Guarani and Kaiowá Peoples’ Human Right to Adequate Food and Nutrition – a holistic approach”, which was written by Thaís Franceschini and Valéria Burity and revised by Flavio Valente and An- gélica Castañeda Flores. The document in which this Executive Summary is based offers an interpretation of the socio-economic and nutritional research that FIAN Brazil and CIMI-MS (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - Regional Mato Grosso do Sul: Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples - Mato Grosso do Sul Region) carried out in 2013 in three emblematic communities – Guaiviry, Ypo’i and Kurusu Ambá. The research in reference was coordinated by Célia Varela (FIAN Brazil) and CIMI-MS, and it was carried out by a team of specialists, consultants and contributors responsible for the fieldwork and the data system- atization. -

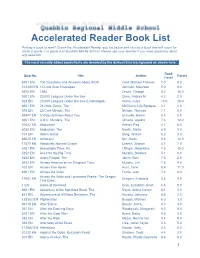

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

To Download The

4 x 2” ad EXPIRES 10/31/2021. EXPIRES 8/31/2021. Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! E dw P ar , N d S ay ecu y D nda ttne August 19 - 25, 2021 , DO ; Bri ; Jaclyn Taylor, NP We offer: INSIDE: •Intimacy Wellness New listings •Hormone Optimization and Testosterone Replacement Therapy Life for for Netlix, Hulu & •Stress Urinary Incontinence for Women Amazon Prime •Holistic Approach to Weight Loss •Hair Restoration ‘The Walking Pages 3, 17, 22 •Medical Aesthetic Injectables •IV Hydration •Laser Hair Removal Dead’ is almost •Laser Skin Rejuvenation Jeffrey Dean Morgan is among •Microneedling & PRP Facial the stars of “The Walking •Weight Management up as Season •Medical Grade Skin Care and Chemical Peels Dead,” which starts its final 11 starts season Sunday on AMC. 904-595-BLUE (2583) blueh2ohealth.com 340 Town Plaza Ave. #2401 x 5” ad Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 One of the largest injury judgements in Florida’s history: $228 million. (904) 399-1609 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN ‘The Walking Dead’ walks What’s Available NOW On into its final AMC season It’ll be a long goodbye for “The Walking Dead,” which its many fans aren’t likely to mind. The 11th and final season of AMC’s hugely popular zombie drama starts Sunday, Aug. 22 – and it really is only the beginning of the end, since after that eight-episode arc ends, two more will wrap up the series in 2022. -

Evil in the 'City of Angels'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! April 24 - 30, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 W L M C A B L R G R C S P L N Your Key 2 x 3" ad P E Y S W Z A Z O V A T T O F L K D G U E N R S U H M I S J To Buying D O I B N P E M R Z Y U S A F and Selling! N K Z N U D E U W A R P A N E 2 x 3.5" ad Z P I M H A Z R O Q Z D E G Y M K E P I R A D N V G A S E B E D W T E Z P E I A B T G L A U P E M E P Y R M N T A M E V P L R V J R V E Z O N U A S E A O X R Z D F T R O L K R F R D Z D E T E C T I V E S I A X I U K N P F A P N K W P A P L Q E C S T K S M N T I A G O U V A H T P E K H E O S R Z M R “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lewis (Michener) (Nathan) Lane Supernatural Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Magda (Natalie) Dormer (1938) Los Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Tiago (Vega) (Daniel) Zovatto (Police) Detectives Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Evil in the Peter (Craft) (Rory) Kinnear Murder County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Maria (Vega) (Adriana) Barraza Espionage Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘City of Angels’ for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com Natalie Dormer stars in “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels,” All specials are pre-paid. -

Interdisciplinary Journal of the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric

Interdisciplinary Journal of the William J. Perry Volume 14 2013 Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies ISSN: 1533-2535 Special Issue: The Drug Policy Debate FOREIGN POLICY AND SECURITY ISSUES THE DRUG POLICY DEBATE Michael Kryzanek, China, United States, and Latin A Selection of Brief Essays Representing America: Challenges and Opportunities the Diversity of Opinion, Contributors: Marilyn Quagliotti, Timothy Lynch, Hilton McDavid and Noel M. Cowell, A Peter Hakim (with Kimberly Covington), Perspective on Cutting Edge Research for Crime and Craig Deare, AMB Adam Blackwell, and Security Policies and Programs in the Caribbean General (ret.) Barry McCaffrey Tyrone James, The Growth of the Private Security Industry in Barbados: A Case Study BOOK REVIEWS Phil Kelly, A Geopolitical Interpretation of Security Joseph Barron: Review of Max Boot, Concerns within United States–Latin American Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Relations Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present Emily Bushman: Review of Mark FOCUS ON BRAZIL Schuller, Killing With Kindness: Haiti, Myles Frechette and Frank Samolis, A Tentative International Aid, and NGOs Embrace: Brazil’s Foreign and Trade Relations with Philip Cofone: Review of Gastón Fornés the United States and Alan Butt Philip, The China–Latin Salvador Raza, Brazil’s Border Security Systems America Axis: Emerging Markets and the Initiative: A Transformative Endeavor in Force Future of Globalisation Design Cole Gibson: Review of Rory Carroll, Shênia K. de Lima, Estratégia Nacional de Defesa Comandante: -

Shots in the Mirror. Crime Films and Society

SHOTST IN THE MIRROR This page intentionally left blank SHOTS IN THE MIRROR Crime Films and Society Nicole Rafter OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2000 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2000 by Nicole Rafter Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rafter, Nicole Hahn, 1939- Crime films and society/ Nicole Rafter, p. cm. Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical reference and index. ISBN 0-19-512982-2; 0-19-512983-0 (pbk.) 1. Gangster films—History and criticism. 2. Police films-—History and criticism. 3. Prison films—History and criticism. 4, justice, Administration of, in motion pictures. 5. Motion pictures—Social aspects—United States. I. Title. PN1995.9. G3R34 2000 791.43'655— dc21 9933411 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper FOR CHARLES ALEXANDER HAHN This page intentionally left blank Preface Some will say I wrote this book so I could spend a couple of years watching movies. While there may be some truth to that, I prefer to think that the book grew out of my misgivings about the way my col- leagues and I were teaching criminology courses. -

Sunday Morning, May 19

SUNDAY MORNING, MAY 19 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Your Voice, Your Paid This Week With George Stepha- Paid Paid 2/KATU 2 2 Vote nopoulos (N) (cc) (TVG) 5:30 Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) Busytown Mys- On the Money Paid Garden Time 6/KOIN 6 6 teries (TVY7) With Bartiromo NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) Cycling Tour of California, Stage 8. (N) (Live) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Zebra trek across the NOVA Analysis of the Neander- 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Makgadikgadi Pans. (TVPG) thal genome. (cc) (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Paid Paid Paid Zoom ★ (‘06) Tim Allen, Courteney Cox Arquette. 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) An ex-superhero mentors ragtag children. ‘PG’ Paid Paid David Jeremiah Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- David Jeremiah Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With Time for a 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (cc) Hagin (TVG) (cc) (TVG) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

Sunday Morning, Feb. 24

SUNDAY MORNING, FEB. 24 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Your Voice, Your NBA Countdown NBA Basketball Los Angeles Lakers at Dallas Mavericks. (N) (Live) 2/KATU 2 2 Vote (N) (Live) (cc) Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation (N) (cc) Paid Bull Riding PBR Built Ford Tough College Basketball Cincinnati at 6/KOIN 6 6 Invitational. (Taped) (cc) Notre Dame. (N) (Live) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Golf Central Live PGA Tour Golf WGC Accenture 8/KGW 8 8 (N) (cc) Match Play Championship, Finals. Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature A Murder of Crows. Crows NOVA What motivates people to 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge are intelligent animals. (TVPG) kill. (cc) (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) Fusion Evolution 2013 Daytona 500 (N) (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) (N) (cc) Paid Paid David Jeremiah Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- David Jeremiah Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With Time for Change 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (cc) Hagin (TVG) (cc) (TVG) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

Maggie Siff Still Enjoys Handling 'Billions'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! May 1 - 7, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 S L P E I F W P S L Z A R V E Your Key 2 x 3" ad C Y K O Q Q U E N D O R E C N U B V C H U C K W L W Y N K A To Buying R N O L E N R C U E S A V I N and Selling! M D L B A W Y L H W N X T W J 2 x 3.5" ad B U K I B B E X L I C R H E T A C L L V Y W N M S K O I K S W L A S U A B O D U T M S E O A E P T W U D S B Y E Y I S G U N U O H C A P I T A L F K N C E V L B E G A B V U P F A E R M W L V K R B W G R F O W F “Billions” begins its G I A M A T T I R I V A L R Y fifth season Sunday D E Z E B I F A N R J K L F E on Showtime. -

The Changing Topography of Contemporary French Policier in Visual and Narrative Media

Deathly Landscapes: The Changing Topography of Contemporary French Policier in Visual and Narrative Media DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paige M. Piper, M.A. Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret C. Flinn, Advisor Jennifer Willging Patrick Bray Copyrighted by Paige M. Piper 2016 Abstract This dissertation explores spatio-temporal shifts in twenty-first century French crime narratives, through a series of close readings of contemporary crime films, television, literature, and comics. The works examined rely on the formal properties of the policier genre but adapt its standard conventions, most notably with deviations in the use and function of space. In this dissertation, I demonstrate that the modern policier is one that embraces its spatio-temporal, social, and generic non-fixity. The textual/visual constructions of many hyper-contemporary crime narratives contain multiple modes of decomposition within: a decentralization of space, which moves the action away from the genre’s traditionally urban location to boundless rural spaces and border zones; a de- concentration of the policier genre, through the incorporation of tropes from other literary styles and works; and a devolution of social cohesion and community identity in the narratives. Chapter 1 examines works where historic references and urban legends of the 19th century fantastique literary genre unfold in modern rural locations. The past and the present converge to problematize modern ideals, identity, and community unity in rural spaces where reason is pitted against the supernatural. -

RML Spring 2021 Rights Guide

NON-FICTION TO STAND AND STARE: How To Garden While Doing Next to Nothing Andrew Timothy O’Brien There’s a lot of advice out there that would tell you how to do numerous things in your garden. But not so much that invites you to think about how to be while you’re out there. With increasingly busy lives, yet another list of chores seems like the very last thing any of us needs when it comes to our own practice of self-care, relaxation and renewal. After all, aren’t these the things we wanted to escape to the garden for in the first place? Put aside the ‘Jobs to do this week’ section in the Sunday papers. What if there were a more low-intervention way to On submission Spring 2021 garden, some reciprocal arrangement through which both you and your soil get fed, with the minimum degree of fuss, effort and guilt on your part, and the maximum measure of healthy, organic growth on that of your garden? In To Stand and Stare, Andrew Timothy O’Brien weaves together strands of botany, philosophy and mindfulness to form an ecological narrative suffused with practical gardening know-how. Informed by a deep understanding and appreciation of natural processes, O’Brien encourages the reader to think from the ground up, as we follow the pattern of a plant’s growth through the season – roots, shoots, and fruits – while advocating an increased awareness of our surroundings. ANDREW TIMOTHY O’BRIEN is an online gardening coach, blogger and host of the critically acclaimed Gardens, Weeds & Words podcast. -

Napavine Man Who Risked Life Trying to Save Driver from Burning Vehicle Gets Prestigious Honor / Main 14

Toledo Schools Hoping to Approve Deal With Ron Reynolds / Main 3 $1 Midweek Edition Thursday, Aug. 23, 2012 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com A ‘Mystery’ No More Napavine Man Who Risked Life Trying to Save Driver From Burning Vehicle Gets Prestigious Honor / Main 14 Twin Cities Survives Pool Play at World Series / Sports 1 Judge to Determine if Murder Suspect Will Stand Trial / Main 6 New Church Moving Into Old Centralia Temple / Main 4 Pete Caster / [email protected] United States Navy Chief Hull Maintenance Technician Aaron Lyons, 33, Napavine, holds his Navy Marine Corps Medal he received after he attempted to save a man from his burning semi-truck last last year. Weather Final Resting Place Deaths Green, Lynnette Maydene, 69, Centralia TONIGHT: Low 50 Coroner’s Office Buries Tryon, Jerry E., 83, Vader Tenino Police TOMORROW: High 70 Unclaimed Remains / Main 16 Boone, Richard A., 80, Toledo Partly Cloudy Spencer, Jean, 78, Winlock see details on page Main 2 Chief Hopes to Weather picture by Dillon The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Stabilize His Coleman, fifth grade, Lewis County Area Since 1889 Onalaska Elementary Department / School Main 5 CH475848cz.cg Main 2 The Chronicle, Centralia/Chehalis, Wash., Thursday, Aug. 23, 2012 COMMUNITY CALENDAR / WEATHER Community Calendar Editor’s Best Bet Lunch, noon, $3 suggested donation Today Pinochle tournament, 1 p.m. Morton Senior Center, 496-3230 Pacific County Tai Chi exercise, 8:30-9 a.m. Open recreation, pool, 9 a.m.-3 p.m. Fair Continues Pinochle, 10 a.m. Through Saturday Crafters 10 a.m.-2:20 p.m.