TWO TRIUMPHS to GO, PLEASE… by John Shuck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belly Bracket

Bike Information and Sizes Fork Size Jack Belly Frame Fork Size Bike Name New Style Stand Bracket Size Old Style Suspension Suspension Size UPDATED LIST 04-22-16 2 parts - Leaf springs and 3 parts - Leaf springs & Suspension Fork Suspension Fork & Suspension arm A1 Honda GL 1500 (1988-2000) *** B Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” 3" 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A2 Honda GL 1200 (1984-1987) *** B Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 2 ½” 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A3 Honda GL 1100 (1980-1983) *** B Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 2 ½” 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A4 Honda Valkyrie (1997-2003) B Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” 3 ½” 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A5 Honda Shadow ACE 1100 (1995-1999) D Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” 3" 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs Honda Shadow Aero 1100 (1999-2002) D Short Solid Forks 16 ½” Short Forks 5” 3” (Note: Shadow Aero uses different rear axle 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs brackets) A6 Honda Shadow ACE 750 (Chain Drive)(1998-03) A Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 3" Honda Shadow Spirit 750 (VT750DC) (Chain 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs Drive) (2001-2007) Honda Shadow Black Widow 750 (2001-2003) A7 Honda Shadow Spirit 1100 (1996-2008) A Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 3" Honda Shadow Sabre 1100-(2000-2008 use D D 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs frame) 2000-08 Sabre 1100uses 2000-08 Sabre 1100 uses 3” Honda Shadow 1100 (‘85-‘96) without a center Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” stand 18 ½” -

American Thunder, from the Ashes of the Buell Motorcycle Company Rose a New Company – Erik Buell Racing

Published by: Chris & Jane Jessop. UK Buell Enthusiasts Group PO Box 271 Dewsbury Thunder WF12 0WA American Tel: 01924 518224 (evening) Newsletter Of The Independent [email protected] Spring 2010 UK Buell Enthusiasts Group UK Buell Enthusiasts Group Erik Buell Racing – American Racing Sportbikes As detailed in the Winter 2009/2010 issue of American Thunder, from the ashes of the Buell Motorcycle Company rose a new company – Erik Buell Racing. After just a few short months Erik Buell and his small team have redes- igned their web site and fully established the new company as a going concern. Their new web site contains full details of the 1125R DSB, 1125RR ASB and 1190RR race machines and a web shop where various Buell race com- ponents can be ordered on-line. The new web site address is www.ebracing.com With the kind permission of Erik Buell we‘ve reproduced some of the information from his new web site on pages 25 to 28. ———————————————— Erik Buell Racing 1190RR This issue contains a major feature on the Buell Thunderbolt series of motorcycles. Although not a very popular model on this side of the Atlantic, the S2/S3 Thunderbolts do have a small and dedicated following. See pages 6 to 19 for a full appraisal of this model. ———————————————— Also in this issue is a preview of our 2010 events calendar. One of UKBEG‘s main strengths has always been the number of Buell events it organises – see pages 20 to 24 for details. Contents: Page 2: UKBEG Emma Radford Memorial. Page 2 & 3: Buell Motorcycle Company – The Final Days. -

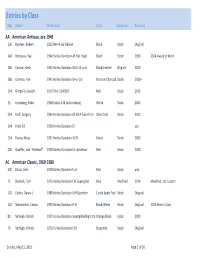

Entries by Class Reg Owner Motorcycle Color Condition Restored

Entries by Class Reg Owner Motorcycle Color Condition Restored AA American Antique, pre 1946 230 Batsleer, Robert 1922 Ner-A-Car Deluxe Black Stock Original Admin Notes: 146 Bordeaux, Ray 1940 Harley-Davidson 45 Flat Head Black Stock 1999 2014Admin Award Notes: of Merit 280 Cannon, Keith 1942 Harley Davidson WLA 45 cu in Black/Leather Original 2014 Admin Notes: 286 Cordero, Yoel 1941 Harley Davidson Servi-Car Maroon/Charcoal Stock 2016+ Admin Notes: 104 Gimpel Jr, Joseph 1913 Thor 13W393 Red Stock 2016 Admin Notes: 15 Grossberg, Mike 1938 Indian 438 (with sidecar) White Stock 2006 Admin Notes: 254 Kniff, Gregory 1943 Harley Davidson 42 WLA Solo-US Ar Olive Drab Stock 2012 Admin Notes: 304 Pratt, Ed 1929 Harley Davidson JD yes Admin Notes: 134 Rivera, Missy 1931 Harley Davidson VL74 Green Stock 2005 Admin Notes: 206 Stauffer, Jack "Flathead" 1940 Harley-Davidson UL w/sidecar Red Stock 2010 Admin Notes: AC American Classic, 1969-1980 300 Blood, John 1978 Harley Davidson FLH Red Stock unk Admin Notes: 72 Bodwell, Tom 1975 Harley Davidson FXE Superglide Blue Modified 2014 Modified,Admin Notes: not Custom 102 Corbin, Danny L 1980 Harley Davidson XLH Sportster Candy Apple Red Stock Original Admin Notes: 120 Manchester, Carson 1970 Harley Davidson FLH Black/White Stock Original 2014Admin Best Notes: in Class 80 McHugh, Patrick 1971 Harley Davidson Superglide/Night tra Orange/Black Stock 2009 Admin Notes: 79 McHugh, Patrick 1972 Harley-Davidson FLH Burgundy Stock Original Admin Notes: Sunday, May 15, 2016 Page 1 of 16 185 Sykes, Joseph 1975 Harley -

NOVEMBER BOOK.Indb

Complete Monterey Coverage 209 Cars Rated SportsKeith Martin’s Car Market The Insider’s Guide to Collecting, Investing, Values, and Trends Scruffy Talbot Miles Collier on history, patina, and $4.8m of charm ►► Ferrari,Ferrari, aa marketmarket inin transitiontransition ►► Gooding’sGooding’s BugattiBugatti bonanzabonanza ►► PhilPhil HillHill 1927–20081927–2008 November 2008 www.sportscarmarket.com Bike Buys BMW K-bike BMW’s Very Special K Early Ks were shunned by boxer purists like Amish with iPods. Only later were they accepted as exceptional, utterly reliable machines by Ed Milich hen the BMW K75 and ers of their time. The same K100 engine K100 made their U.S. powered “naked,” RS, and RT variants debut for the 1985 model of the bike. year, BMW motorcycle W K engines surpass life loyalists hailed the bikes as a sign of the apocalypse. of boxers Unlike their pushrod, 2-valve, air- The RS had a low sport fairing that cooled boxer twins, BMW’s K-bikes, created an effective pocket of still air (aka “Flying Bricks”) featured 3- or 4- around the rider, while the K100RT cylinder, DOHC, water-cooled motors. featured a large touring fairing. The machine still utilized the automo- The K100RT later evolved into tive-style dry clutch and shaft final the K100LT designation (colloquially drive found in boxers. Fit, function, known as “Light Truck”), with an all-en- and finish also remained impeccably compassing fairing, integral radio, and Bavarian. other comforts. K75s came in a “naked” But BMW seemed to abandon build- variant, a café-faired K75C, and also the ing “motorcycles for the proletariat” for desirable sporting K75S. -

Technical Regulations 2020

Technical Regulations 2020 Published on November 28, 2019 AIM • The aim of the European Endurance Legend Cup (EELC) is to enable all European classic race machines built up to and including December 1986 to race together in a true European classic endurance series. • Machines in all classes must have a classic period appearance and have a minimum engine size of 349cc. All machines will be eligible to race in the EELC with their home race club certification (Eligibility Certificate) or single event EELC eligibility. OVERARCHING CONTROL OF REGULATIONS • The interpretation of these regulations is entirely the province of the Series Organisers whose decisions on any matter concerning these regulations must be considered final and binding. • The Series Organisers reserve the right, in exceptional circumstances, to accept the entry of a motorcycle, which does not exactly comply with these regulations if they think that the bike will add significant value to any of the series events. Such machines may be eligible for awards but will not be eligible for Championship points. CONFORMITY • Any breach of these rules unless rectified before the start of any race, will be sanctioned by the disqualification of the team concerned for the event during which the infraction will be noted. The Jury's decision is irrevocAble And binding. TECHNICAL REGULATION 2020 [email protected] 1 CLASSES CLASSIC: 31/12/1968 to 31/12/1981 Engine 4-T air-cooled only 2-T air or water-cooled 2-Valve engine displacement limited to 1300cc 4-Valve engine displacement limited to 1000cc -

Bike Info & Sizes

Bike Information and Sizes Fork Size Jack Belly Frame Fork Size Bike Name New Style Stand Bracket Size Old Style Suspension Suspension Size UPDATED LIST 04/05/18 2 parts - Leaf springs and 3 parts - Leaf springs & Suspension Fork Suspension Fork & Suspension arm A1 Honda GL 1500 (1988-2000) *** B Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” 3" 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A2 Honda GL 1200 (1984-1987) *** B Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 2 ½” 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A3 Honda GL 1100 (1980-1983) *** B Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 2 ½” 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A4 Honda Valkyrie (1997-2003) B Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” 3 ½” 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs A5 Honda Shadow ACE 1100 (1995-1999) D Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” 3" 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs Honda Shadow Aero 1100 (1999-2002) D Short Solid Forks 16 ½” Short Forks 5” 3” (Note: Shadow Aero uses different rear axle 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs brackets) A6 Honda Shadow ACE 750 (Chain Drive)(1998-03) A Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 3" Honda Shadow Spirit 750 (VT750DC) (Chain 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs Drive) (2001-2007) Honda Shadow Black Widow 750 (2001-2003) A7 Honda Shadow Spirit 1100 (1996-2008) A Med Solid Forks 17 ½” Medium Forks 6 ¼” 3" Honda Shadow Sabre 1100-(2000-2008 use D D 18 ½” leaf springs 18 ½” leaf springs frame) 2000-08 Sabre 1100uses 2000-08 Sabre 1100 uses 3” Honda Shadow 1100 (‘85-‘96) without a center Long Solid Forks 20 ½” Long Forks 9” stand 18 ½” -

BMW K1 Produzione

BMW Serie K 100 2V 4V Tabella riepilogativa della produzione year K100/1 K100RS K100RT K100LT K100/2 K1 K100RS 16V totali 1983 4.601 2.661 3 7.265 1984 4.089 11.149 8.234 23.472 1985 1.932 7.173 6.726 15.831 1986 630 5.656 3.622 1.236 11.144 1987 287 3.883 2.318 2.828 251 9.567 1988 10 3.074 1.014 2.306 566 12 6.982 1989 1.208 418 3.420 351 3.574 760 9.731 1990 3.158 154 2.120 5.976 11.408 1991 1.951 763 5.057 7.771 1992 310 873 1.183 1993 142 142 totali 11.549 34.804 22.335 14.899 1.322 6.921 12.666 104.496 year pezzi BMW K100 Basic 1983 4.601 1984 4.089 1985 1.932 1986 630 1987 287 1988 10 Produzione Pezzi anno mese Codice dal telaio al telaio Codice Start (US) End (US) EU US totale note 1982 5 501 0000001 0000019 19 - 19 1983 4 501 0000020 0000040 21 - 21 1983 5 501 0000041 0000146 106 - 106 1983 6 501 0000147 0000259 113 - 113 1983 8 501 0000260 0001015 756 - 756 1983 9 501 0001016 0002593 1.578 - 1.578 1983 10 501 0002594 0004094 1.501 - 1.501 1983 11 501 0004095 0004444 350 - 350 1983 12 501 0004445 0004697 253 - 253 1984 1 501 0004698 0005118 421 - 421 1984 2 501 0005119 0005727 609 - 609 1984 3 501 0005728 0006233 511 0030001 0030007 506 7 513 1984 4 501 0006234 0006616 511 0030008 0030008 383 1 384 1984 5 501 0006617 0006799 511 0030009 0030021 183 13 196 1984 7 501 0006800 0006828 511 0030022 0030337 29 316 345 1984 8 501 0006829 0006879 511 0030338 0030762 51 425 476 1984 9 501 0006880 0007010 511 0030763 0030915 131 153 284 1984 10 501 0007011 0007264 511 0030916 0031105 254 190 444 1984 11 501 0007265 0007290 26 - 26 1985 -

Lfre Enormous Sucess of the Kl00 Has Nruyed Tfrc Br Nrny Riihrs

lfreenormous sucess as independentas the BMW Boxer. ofthe Kl00 has nruYed The BMW compact drive system - that meansa highly compact,length- tfrc br nrny riihrs, through pure innovation. wise-mountedo water-cooled, four- cylinderin-line engine which is sofehigh_-perf,olmon@ The K 100gave the highestmotor- extremelyeasyto service.An engine ole morc cycle categorywhat demanding which not only providesthe most /cles riders have always looked for: dynamicof riderswith the perform- nilthan engine reasonableand, more particularly, anceand torque they demand,but controllable h igh performance. which can also work in completehar- ourpur As fascinating as high performances mony with this style of riding thanks wereon the one hand,they also gave to its light weight and low centre :"t rise to concern,since this category of gravity.The logicaldireet drive to of machinecan normallyonly fully the universalshaft eliminatesthe loss exploit its primaryfeature - maximum of power which otheruviseoccurs powerwith top enginespeed and due to the double reversalof the drive. hecticgear changing - on closed Anyonewho knows how to evaluate motorcycle racetracks. A dubious motorcycle "pleasure", engineswill immediately and normallyonly possi- recognizethat the BMW K engine ble by increasingthe risk of problems unit is speciallydesigned to meetthe in handlingand controllability. demandsof a powerful motorcycle. The disadvantagesof this develop- From now on, this unique,advanced ment are particularlynoticeable in technologyis also availablein the those areaswhere motorcycling is at 750class. After extensive studies and its most fascinating- on winding tests, we have now transferred this roads,uphill and down.The advan- trend-settingconcept to the 3-cylinder tages now offered by BMWare based in-lineengines of the new K75. -

Getting to Know Neil Warden

In this piece, Neil Warden, a key player in our Group, having been Chairman on at least 3 occasions, is currently our Group Secretary as well as one of our Local Observer Assessors and Bike Observer Liaison. Here Neil tells us about his machines and experiences. When did you pass your bike test and what was your first machine? I passed my bike test back in the 90'. I had a Honda 125cc, a great little bike. What particular things do you remember about your early biking years? 2 stroke engines, noisy, smells and not much power, but good fun Honda VFR 750 Can you tell us all the different bikes that you’ve ridden / owned? • Honda's ER50 Honda 90 (super cub), no clutch, had a step through gear system, took a bit of getting used to. • Honda 250 Super dream • Yamaha 125 DT MX • Kawasaki chopper • Kawasaki 400 • Kymco 125 Honda ST 1300 Current bikes in the fleet? • Honda ST 1300 Pan European, recently purchased • Honda ST1100 Pan European (Currently being rebuild/restored • Honda VFR 750, owned for over 15 years • BMW K100 LT, I used this as my training bike when I taught learners and still have it. Ex police bike. Honda ST 1100 What is or has been the best bike that you’ve owned and why? Honda VFR, very agile and great all-round bike. You can go touring with it one day then do a track day the next. Do you regret selling any particular bike? No What has been your most exhilarating moment on a bike? Doing the NC 500 around Scotland with my son and his friend. -

Technical Regulations

Technical Regulations ENGINES • Engines are preferred to have working starter motors and generators • Any machine not having a working starter motor will start at the back/rear of the grid irrelevant of the team’s qualification time • Engine tuning or modification in the Superstock class is forbidden. Superstock machines engines must remain as manufactured. Only replacement / aftermarket clutch springs, plates and oil filters are allowed • It is mandatory to preserve the particularities of the series models such as the number of cylinders, the number of gear ratios, the number of camshafts, etc • The engine crankcases must remain in conformity with the original. However, internal modifications to these housings are permitted • The cylinder block, cylinder head and cylinder head cover must correspond to the original model of the engine • Crankshaft and rods are free • Camshafts are free • The addition of a pump to create a vacuum in the crankcase is forbidden • Side covers can be modified or replaced • Ducati 900SS engines up to 1989, prior to but not including the DS or EVO engine are allowed (Appendix 2) CLUTCH • The original clutch can be changed or replaced • No electric source may be used for clutch operations • The clutch system (in oil bath or dry) and its control (cable / hydraulic) must remain as standard fitment • No form of slipper clutch or traction control is permitted TRANSMISSIONS • All gears, shafts, shift drum and shift forks are free • The gearbox output gear shall be covered by a metal guard • A metal casing must completely cover the primary chain on motorcycles with a separate box. -

Issue 21 2016

POLICE LINE - DO NOT CROSS - POLICE LINE - DO NOT CROSS -POLICE LINE www.policebikes.org.uk 2016 issue 21 HISTORIC MOTORCYCLE POLICE GROUP NEWSLETTER HPMG are sponsored by HISTORIC POLICE MOTORCYCLE GROUP NEWSLETTER www.hgbmotorcycles.co.uk www.honda.co.uk www.yamaha-motor.eu/uk POLICE LINE - DO NOT CROSS - POLICE LINE - DO NOT CROSS -POLICE LINE HISTORIC POLICE MOTORCYCLE GROUP David’s Page Welcome everyone to 2016 First of all we have to thank everyone who attended the events and shows in 2015, they put on an excellent display and the feed back was very helpful, well done. Remember that by showing of your ex-police motorcycles, you are giving the public a chance to see something unique and rare. It doesn’t matter whether it is still in police livery or has been put back into civilian trim, they were all working bikes and deserve to be appreciated. Please check out the full list of events on the back page for this year and come along to as many as you can. The more vehicles on show the better. Check out the photo's as shown in this newsletter and if you locate any new or unusual ones please pass on to Paul for future display in the newsletter. Have a great summer and see you all at the events. Remember, Enjoy Yourselves. David Bragg Pictures from the Archive - Home Office 2 HISTORIC POLICE MOTORCYCLE GROUP Pictures from the Archive - Home Office The pictures on both pages are from the Home Office and are dated between 1992 and 1993 and show various demonstrators from Suzuki together with the final police spec models from BMW and Honda. -

Shaft Drive Lines November 2011

Member of BMW Clubs International Council www.bmw-clubs-international.com Shaft Drive Lines November 2011 Look Out For The Club meets at the Harmonie German Club Canberra, 49 Jerrabomberra Avenue Narrabundah ACT. November, Friday 4 - Sunday 6. 17th Trout Rally at Three Mile Dam. November Sunday 6. Alternate Breakfast at Captains Flat November Saturday 19 – Sunday 20. Overnight ride to Cootamundra and Temora Aviation Show on Sunday before returning to Canberra. December Friday 9. Club Awards Night & Christmas Dinner. Book Now! SHAFT DRIVE LINES ABOUT THE CLUB VOLUME 31, NOVEMBER 2011 Meetings: 7.45 pm, fourth Monday of each month at the Harmonie German Club 2011-12 COMMITTEE Canberra 49 Jerrabomberra Ave, Narrabundah, ACT or by Google Map. Membership: Check this magazine for a membership form or down load one President: Mark Edwards - R1200GS from the Club’s website http://bmwmccact.org.au/. (02) 6125 5530 (w) Web Site: Check the Club’s website http://www.bmwmccact.org.au for updates to 04282 58676 rides and social events and keep in touch by joining one of our Yahoo groups: [email protected] • BMWMCCACT: http://autos.groups.yahoo.com/group/actbmwmcc/. Vice President: • ACTGravelsurfers: http://autos.groups.yahoo.com/group/ACTGravelsurfing/. Ian Warren - K1200GT H 02 6166 1466 C 04 1478 9632 Activities: The Club endeavours to have at least one organized run and social event per month and listed on the What’s On page and welcomes suggestions for [email protected] rides or social events. Send your suggestions to the Ride Coordinator or Social Secretary. Secretary: Gary Melling – R1200GSA Whilst we make every effort to keep the What’s On page accurate, changes to 0410 142 835 meeting times and places can occur between publication dates.