REA for the Door County Parks Planning Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARDINAL-HICKORY CREEK 345 Kv TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT MACRO-CORRIDOR STUDY

CARDINAL-HICKORY CREEK 345 kV TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT MACRO-CORRIDOR STUDY Submitted to: United States Department of Agriculture’s Rural Utilities Service (“RUS”) Applicant to RUS: Dairyland Power Cooperative Other participating utilities in the Cardinal-Hickory Creek Transmission Line Project: • American Transmission Company LLC, by its corporate manager ATC Management Inc. • ITC Midwest LLC September 28, 2016 Macro-Corridor Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page No. 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Basis for this Macro-Corridor Study.................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Environmental Review Requirements and Process ............................................. 1-2 1.3 Project Overview ................................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 Overview of Utilities’ Development of a Study Area, Macro-Corridors and Alternative Corridors ........................................................................................... 1-4 1.5 Purpose and Need ................................................................................................ 1-2 1.6 Outreach Process .................................................................................................. 1-2 1.7 Required Permits and Approvals ......................................................................... 1-3 2.0 TECHNICAL ALTERNATIVES UNDER EVALUATION .................................. -

Microplastics in Beaches of the Baja California Peninsula

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Chemical Sciences and Engineering Department MICROPLASTICS IN BEACHES OF THE BAJA CALIFORNIA PENINSULA TERESITA DE JESUS PIÑON COLIN FERNANDO WAKIDA KUSUNOKI Sixth International Marine Debris Conference SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA, UNITED STATES 7 DE MARZO DEL 2018 OUTLINE OF THE PRESENTATION INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGY RESULTS CONCLUSIONS OBJECTIVE. The aim of this study was to investigate the occurrence and distribution of microplastics in sandy beaches located in the Baja California peninsula. STUDY AREA 1200 km long and around 3000 km of seashore METHODOLOGY SAMPLED BEACHES IN THE BAJA CALIFORNIA PENINSULA • . • 21 sampling sites. • 12 sites located in the Pacific ocean coast. • 9 sites located the Gulf of California coast. • 9 sites classified as urban beaches (U). • 12 sites classified as rural beaches (R). SAMPLING EXTRACTION METHOD BY DENSITY. RESULTS Bahía de los Angeles. MICROPLASTICS ABUNDANCE (R) rural. (U) urban. COMPARISON WITH OTHER PUBLISHED STUDIES Area CONCENTRATIÓN UNIT REFERENCE West coast USA 39-140 (85) Partícles kg-1 Whitmire et al. (2017) (National Parks) United Kigdom 86 Partícles kg-1 Thompson et al. (2004) Mediterranean Sea 76 – 1512 (291) Partícles kg-1 Lots et al. (2017) North Sea 88-164 (190) Particles Kg-1 Lots et al. (2017) Baja California Ocean Pacific 37-312 (179) Particles kg-1 This study Gulf of 16-230 (76) Particles kg-1 This study California MORPHOLOGY OF MICROPLASTICS FOUND 2% 3% 4% 91% Fibres Granules spheres films Fiber color percentages blue Purple black Red green 7% 2% 25% 7% 59% Examples of shapes and colors of the microplastics found PINK FILM CABO SAN LUCAS BEACH POSIBLE POLYAMIDE NYLON TYPE Polyamide nylon type reference (Browne et al., 2011). -

Doggin' America's Beaches

Doggin’ America’s Beaches A Traveler’s Guide To Dog-Friendly Beaches - (and those that aren’t) Doug Gelbert illustrations by Andrew Chesworth Cruden Bay Books There is always something for an active dog to look forward to at the beach... DOGGIN’ AMERICA’S BEACHES Copyright 2007 by Cruden Bay Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cruden Bay Books PO Box 467 Montchanin, DE 19710 www.hikewithyourdog.com International Standard Book Number 978-0-9797074-4-5 “Dogs are our link to paradise...to sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring - it was peace.” - Milan Kundera Ahead On The Trail Your Dog On The Atlantic Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Gulf Of Mexico Beaches 6 Your Dog On The Pacific Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Great Lakes Beaches 0 Also... Tips For Taking Your Dog To The Beach 6 Doggin’ The Chesapeake Bay 4 Introduction It is hard to imagine any place a dog is happier than at a beach. Whether running around on the sand, jumping in the water or just lying in the sun, every dog deserves a day at the beach. But all too often dog owners stopping at a sandy stretch of beach are met with signs designed to make hearts - human and canine alike - droop: NO DOGS ON BEACH. -

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Evolution of Glacial & Coastal Landforms

1 GEOMORPHOLOGY 201 READER PART IV : EVOLUTION OF GLACIAL & COASTAL LANDFORMS A landform is a small to medium tract or parcel of the earth’s surface. After weathering processes have had their actions on the earth materials making up the surface of the earth, the geomorphic agents like running water, ground water, wind, glaciers, waves perform erosion. The previous sections covered the erosion and deposition and hence landforms caused by running water (fluvial geomorphology) and by wind (aeolian geomorphology). Erosion causes changes on the surface of the earth and is followed by deposition, which likewise causes changes to occur on the surface of the earth. Several related landforms together make up landscapes, thereby forming large tracts of the surface of the earth. Each landform has its own physical shape, size, materials and is a result of the action of certain geomorphic processes and agents. Actions of most of the geomorphic processes and agents are slow, and hence the results take a long time to take shape. Every landform has a beginning. Landforms once formed may change their shape, size and nature slowly or fast due to continued action of geomorphic processes and agents. Due to changes in climatic conditions and vertical or horizontal movements of landmasses, either the intensity of processes or the processes themselves might change leading to new modifications in the landforms. Evolution here implies stages of transformation of either a part of the earth’s surface from one landform into another or transformation of individual landforms after they are once formed. That means, each and every landform has a history of development and changes through time. -

Grass Varieties for North Dakota

R-794 (Revised) Grass Varieties For North Dakota Kevin K. Sedivec Extension Rangeland Management Specialist, NDSU, Fargo Dwight A. Tober Plant Materials Specialist, USDA-NRCS, Bismarck Wayne L. Duckwitz Plant Materials Center Manager, USDA-NRCS, Bismarck John R. Hendrickson Research Rangeland Management Specialist, USDA-ARS, Mandan North Dakota State University Fargo, North Dakota June 2011 election of the appropriate species and variety is an important step in making a grass seeding successful. Grass species and varieties differ in growth habit, productivity, forage quality, drought resistance, tolerance Sto grazing, winter hardiness, seedling vigor, salinity tolerance and many other characteristics. Therefore, selection should be based on the climate, soils, intended use and the planned management. Planting a well-adapted selection also can provide long-term benefi ts and affect future productivity of the stand. This publication is designed to assist North Dakota producers and land managers in selecting perennial grass species and varieties for rangeland and pasture seeding and conservation planting. Each species is described following a list of recommended varieties Contents (releases). Variety origin and the date released are Introduction. 2 included for additional reference. Introduced Grasses . 3 A Plant Species Guide for Special Conditions, found Bromegrass . 3 near the end of this publication, is provided to assist Fescue . 4 in selection of grass species for droughty soils, arid Orchardgrass . 4 Foxtail. 5 or wet environments, saline or alkaline areas and Wheatgrass . 5 landscape/ornamental plantings. Several factors should Timothy. 7 be considered before selecting plant species. These Wildrye . 7 include 1) a soil test, 2) herbicides previously used, Native Grasses . -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

LIGHTHOUSES Pottawatomie Lighthouse Rock Island Please Contact Businesses for Current Tour Schedules and Pick Up/Drop Off Locations

LIGHTHOUSE SCENIC TOURS Towering over 300 miles of picturesque shoreline, you LIGHTHOUSES Pottawatomie Lighthouse Rock Island Please contact businesses for current tour schedules and pick up/drop off locations. Bon Voyage! will find historic lighthouses standing testament to of Door County Washington Island Bay Shore Outfitters, 2457 S. Bay Shore Drive - Sister Bay 920.854.7598 Door County’s rich maritime heritage. In the 19th and Gills Rock Plum Island Range Bay Shore Outfitters, 59 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.818.0431 early 20th centuries, these landmarks of yesteryear Ellison Bay Light Pilot Island Chambers Island Lighthouse Lighthouse Classic Boat Tours of Door County, Fish Creek Town Dock, Slip #5 - Fish Creek 920.421.2080 assisted sailors in navigating the lake and bay waters Sister Bay Rowleys Bay Door County Adventure Rafting, 4150 Maple St. - Fish Creek 920.559.6106 of the Door Peninsula and surrounding islands. Today, Ephraim Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Cana Island Lighthouse Door County Kayak Tours, 8442 Hwy 42 - Fish Creek 920.868.1400 many are still operational and welcome visitors with Fish Creek Egg Harbor Baileys Harbor Door County Maritime Museum, 120 N. Madison Ave. - Sturgeon Bay 920.743.5958 compelling stories and breathtaking views. Relax and Old Baileys Harbor Light step back in time. Plan your Door County lighthouse Baileys Harbor Range Light Door County Tours, P.O. Box 136 - Baileys Harbor 920.493.1572 Jacksonport Carlsville Door County Trolley, 8030 Hwy 42 - Egg Harbor 920.868.1100 tour today. Sturgeon Bay Sherwood Point Lighthouse Ephraim Kayak Center, 9999 Water St. - Ephraim 920.854.4336 Visitors can take advantage of additional access to Sturgeon Bay Canal Station Lighthouse Fish Creek Scenic Boat Tours, 9448 Spruce St. -

Conservation Assessment of Greater Sage-Grouse and Sagebrush Habitats

Conservation Assessment of Greater Sage-grouse and Sagebrush Habitats J. W. Connelly S. T. Knick M. A. Schroeder S. J. Stiver Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies June 2004 CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT OF GREATER SAGE-GROUSE and SAGEBRUSH HABITATS John W. Connelly Idaho Department Fish and Game 83 W 215 N Blackfoot, ID 83221 [email protected] Steven T. Knick USGS Forest & Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center Snake River Field Station 970 Lusk St. Boise, ID 83706 [email protected] Michael A. Schroeder Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife P.O. Box 1077 Bridgeport, WA 98813 [email protected] San J. Stiver Wildlife Coordinator, National Sage-Grouse Conservation Framework Planning Team 2184 Richard St. Prescott, AZ 86301 [email protected] This report should be cited as: Connelly, J. W., S. T. Knick, M. A. Schroeder, and S. J. Stiver. 2004. Conservation Assessment of Greater Sage-grouse and Sagebrush Habitats. Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Unpublished Report. Cheyenne, Wyoming. Cover photo credit, Kim Toulouse i Conservation Assessment of Greater Sage-grouse and Sagebrush Habitats Connelly et al. Author Biographies John W. Connelly Jack has been employed as a Principal Wildlife Research Biologist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game for the last 20 years. He received his B.S. degree from the University of Idaho and M.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Washington State University. Jack is a Certified Wildlife Biologist and works on grouse conservation issues at national and international scales. He is a member of the Western Sage and Columbian Sharp-tailed Technical Committee and the Grouse Specialists’ Group. -

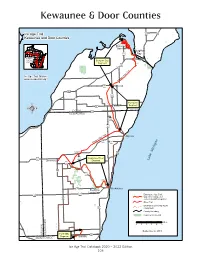

Sturgeon Bay Segment 13.7 Mi

Kewaunee & Door Counties Ice Age Trail 42 57 Kewaunee and Door Counties Potawatomi State Park Sturgeon PD Bay Kewaunee and Door Sturgeon Bay Counties Segment 42 57 il ra T te ta S Ice Age Trail Alliance e pe www.iceagetrail.org na Ah H Maplewood 57 42 C Forestville Forestville Segment J DOOR X KEWAUNEE M D il ra T Algoma ate St ee p 54 n na K Ah a g i h c i M Casco 42 e k 54 C Kewaunee River a Luxemburg Segment L A AB C F Kewaunee Bruemmer County Park 29 29 Existing Ice Age Trail, subject to change as it AB evolves toward completion Other Trail Unofficial Connecting Route 42 (unmarked) County Boundary Public or IATA Land E E Miles N 0 1 2 3 4 5 N U A W O W September 4, 2019 E R K B Tisch Mills BB Segment Tisch Mills MANITOWOC Ice Age Trail Databook 2020 – 2022 Edition 103 87°28' 87°26' 87°24' 87°22' GREEN BAY Sawyer Harbor Shoreline Rd. Eastern Terminus Ice Age Trail P DK2 0.7 Potawatomi P 0.7 Sturgeon State Park 44°52' Rd. Bay N . y 44°52' Norwa 0.3 P 0.3 DK3 0.4 Group P B Camp HH 0.4 L a S r . DK4 s N Rd. o orway n C re Egg Harbor Rd. ek PD M 1.3 Sturgeon Bay Segment 13.7 mi Michigan St. Duluth Av. Duluth GREEN 42 C 57 44°50' BAY Joliet Hickory BUS Av. -

And Sand Bluestem (Andropogon Hallii) Performance Trials North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota

United States Prairie Sandreed Department of Agriculture (Calamovilfa longifolia) Natural Resources and Conservation Service Sand Bluestem Plant Materials Center (Andropogon hallii) June 2011 Performance Trials North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota Who We Are Plants are an important tool for conservation. The Bismarck Plant Materials Center (PMC) is part of the United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resouces Conservation Service (USDA, NRCS). It is one of a network of 27 centers nationwide dedicated to providing vegetative solutions to conservation problems. The Plant Materials program has been providing conservation plant materials and technology since 1934. Contact Us USDA, NRCS Plant Materials Center 3308 University Drive Bismarck, ND 58504 Phone: (701)250-4330 In this photo: Fax: (701)250-4334 Sand bluestem seed that http://Plant-Materials.nrcs.usda.gov has not been debearded Acknowledgements Cooperators and partners in the warm-season grass evaluation trials, together with the USDA, NRCS Plant Materials Center at Bismarck, ND, included: U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service (J. Clark Salyer National Wildlife Refuge near Upham, ND; Wetland Management District at Fergus Falls, MN; and Karl E. Mundt National Wildlife Refuge near Pickstown, SD); South Dakota Department of Agriculture Forestry Division; South Dakota Department of Game, Fish, and Parks; Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Forestry; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; USDA, NRCS field and area offices and Soil and Water Conservation District offices located at Bottineau, ND; Fergus Falls, MN; Lake Andes, SD; Onida, SD; Rochester, MN; and Pierre, SD; Southeastern Minnesota Association of Soil and Water Conservation Districts; Hiawatha Valley Resource Conservation and Development In this photo: Area (Minnesota); and North Central Resource Prairie sandreed seed Conservation and Development Office (South with fuzz removed Dakota). -

Door County Lighthouse Map

Door County Lighthouse Map Canal Station Lighthouse (#3) Sherwood Point Lighthouse (#4) Compliments of the Plum Island Range Light (#6) www.DoorCounty.com Pilot Island Lighthouse (#9) Door County Lighthouses # 2 Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Location: Follow Hwy. 42 to the North end of The Door County Peninsula’s 300 miles of Fish Creek to the entrance of Peninsula State shoreline, much of it rocky, gave need for th Park. You must pay a park admission fee the lighthouses so that sailors of the 19 when you enter the park. Inquire about the th and early 20 centuries could safely directions to the lighthouse at the park’s front navigate the lake and bay waters around entrance. History: The lighthouse was the Door peninsula & surrounding islands. established in 1868 and automated in 1926. Restoration began in 1960 by the Door County # 1 Cana Island Lighthouse Historical Society. The lighthouse has been open for tours since 1964. Welcome: Tours are $4 for adults, $1 for students, and children 5 and under are free. Tour hours are daily from 10-4, late May through mid-October. Tours depart every 30 minutes. The park maintains a parking lot and restrooms adjacent to the grounds. Information: Phone (920) 839-2377 or online at www.EagleBluffLighthouse.org. Maintained and operated by the Door County Historical Society. Tower is only open to public during Lighthouse Walk weekend in May # 3 Canal Station / Pierhead Light Location: Take County Q at the North edge of Baileys Harbor to Cana Island Rd. two and Location: This fully operating US Coast a half miles (Note: Sharp Right Turn on Cana Guard station is located at the Lake Michigan Island Rd).