A Reinterpretation of the Gatehouse at Tonbridge Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Designs Through History: from Simple Mounds to Strong Towers

https://www.exploring-castles.com/castle_designs/ Castle Designs Through History: From Simple Mounds to Strong Towers Castle designs have changed over history. This is because of changes in technology over time – as well as changes to the function and purpose of castles. The first castles were simply ‘mounds’ of earth, and medieval castle designs improved on these basics – adding ditches in the Motte & Bailey design. As technology advanced – and as attackers got more sophisticated – elaborate concentric castle designs emerged, creating a fortress almost impregnable to its enemies. Nowadays, castles are designed for prestige, for fantasy, and to embellish a romantic view of the life of kings, queens and nobles from years gone by. This page gives a brief overview of the history of castles, and explains why different castle designs came about. Fundamentally, these changing designs were due to the changes in the purpose and significance of castles. Early Medieval Times From Norman Times: Motte & Bailey Castles – Simple designs that were quick to build The first castles, built in the Early Middle Ages (early Medieval period), were ‘earthworks’ – mounds of earth primarily built for defence, as enemies struggled to climb them. During the 1000s, the Normans developed these into Motte and Bailey castle designs. Effectively, a ‘Motte’ was a large mound of earth, and a ‘Bailey’ was the flattened area beside the mound. The ‘Motte’ could be surrounded with a ditch, and buildings could be placed on the bailey – made of timber or, if time permitted, stone. The key benefit of Motte & Bailey castles was that they were very quick to build, but pretty difficult to attack. -

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Our Castle, Our Town

Our Castle, Our Town An n 2011 BACAS took part in a community project undertaken by Castle Cary investigation Museum with the purpose of exploring a selection of historic sites in and around into the the town of Castle Cary. archaeology of I Castle Cary's Using a number of non intrusive surveying methods including geophysical survey Castle site and aerial photography, the aim of the project was to develop the interpretation of some of the town’s historic sites, including the town’s castle site. A geophysical Matthew survey was undertaken at three sites, including the Castle site, the later manorial Charlton site, and a small survey 2 km south west of Castle Cary, at Dimmer. The focus of the article will be the main castle site centred in the town (see Figure 1) which will provide a brief history of the site, followed by the results of the survey and subsequent interpretation. Location and Topography Castle Cary is a small town in south east Somerset, lying within the Jurassic belt of geology, approximately at the junction of the upper lias and the inferior and upper oolites. Building stone is plentiful, and is orange to yellow in colour. This is the source of the River Cary, which now runs to the Bristol Channel via King’s Sedgemoor Drain and the River Parrett, but prior to 1793 petered out within Sedgemoor. The site occupies a natural spur formed by two conjoining, irregularly shaped mounds extending from the north east to the south west. The ground gradually rises to the north and, more steeply, to the east, and falls away to the south. -

Place-Names in and Around the Fleet Valley ==== D ==== Daffin Daffin Is a Farm at the Head of the Cleugh of Doon Above Carsluith

Place-names in and around the Fleet Valley ==== D ==== Daffin Daffin is a farm at the head of the Cleugh of Doon above Carsluith. There is a Daffin Tree marked on the 1st edition OS map at Killochy in Balmaclellan parish, and Daffin Hill in this location on current OS maps, across the Dee from Kenmure Castle; Castle Daffin is a hill in Parton parish and a house by Auchencairn. This is likely to be Gaelic *Dà pheiginn ‘two pennylands’. Peighinn is ‘a penny’, but in place-names it refers to a unit of land, based on yield rather than area. It probably originated in the Gaelic-Norse context of Argyll and the southern Hebrides, and was introduced into the south-west by the Gall- Ghàidheil (see Ardwell above). It occurs in place-names in Galloway and, especially, Carrick as ‘Pin- ‘ as first element, ‘-fin’ with ‘softened ‘ph’ after a numeral or other pre-positioned adjective. Originally a pennyland was a relatively small division of a davoch (dabhach, see Cullendoch above), but in the south-west places whose names contain this element appear in mediaeval records as holdings of relatively substantial landowners, comprising good extents of pasture, meadow and woodland as well as the arable core, and yielding much higher taxes than the pennylands further north. Indeed, peighinn may have come to be used more generally in the region for a fairly substantial estate without implying a specific valuation. *Dà pheiginn ‘two pennylands’ would, then, have been a large and productive landholding. However, a Scots origin is also possible, or if the origin was Gaelic, reinterpretation by Scots speakers is possible: daffin or daffen is a Scots word for ‘daffodil’, but as a verb, daffin(g) is ‘playing daft, larking about’. -

Shell Keeps-Catalogue1

Shell-keeps - The Catalogue Fig. 1. Plan of Berkeley Castle prepared for G. T Clark, published in Vol. 1 of Mediaeval Military Architecture, 1884, opposite. p. 229. Berkeley 2. Berkeley er (knocking out an earlier “bastion”) comprising two, Published interpretations of the shell-keep have as- joined rectangular towers which may be an early ex- sumed the following sequence: (a) the motte was part ample of an artillery emplacement and (ii) additions of the castle of William fitzOsbern, documented in and alterations to the forebuilding and (iii) encasement the late 11th century, bearing a structure of which no of the south “bastion” by the new gatehouse to the trace now remains; (b) with the assent and direction inner bailey (e) the siege of 1645 and the slighting of of Henry II in 1154, the new owner, Robert fitzHard- 1646 inflicted damage to the motte and its masonry ing (a rich Bristol merchant, from an English family, structures which were patched up around 1700 (f) who supported the Angevin cause and died in 1170) various 18th- to 20th-century alterations and additions truncated the motte-top, encased the motte in a shell- further masked and/or destroyed the structures, both in keep with battered plinth, a series of pilaster buttress- the domestic ranges (the east range of which is wholly es, (probably) four semi-circular “bastions” and (soon 1920s, as is the rebuilding of the chapel) and in Thor- afterwards) a forebuilding with defended stair rising pe's Tower. from ground level to a doorway on the motte-top, the The castle is unusual in having charter evidence latter being leveled up with the spoil created by relating to its revival under new ownership in the truncating the motte; (c) this shell-keep rose above 1150s, although the authenticity of these charters as the motte, with domestic buildings against its inside contemporary record has been questioned. -

KO DT Y3 Castles

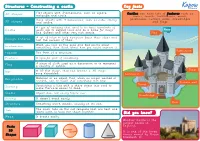

Structures - Constructing a castle Key facts Flat objects with 2-dimensions, such as square, 2D shapes Castles can have lots of features such as rectangle and circle. towers, turrets, battlements, moats, Solid objects with 3-dimensions, such as cube, oblong gatehouses, curtain walls, drawbridges 3D shapes and sphere. and flags. A type of building that used to be built hundreds of Castle years ago to defend land and be a home for Kings and Queens and other very rich people. Flag A set of rules to help designers focus their ideas and Design criteria test the success of them. When you look at the good and bad points about Evaluation something, then think about how you could improve it. Battlement Façade The front of a structure. Feature A specific part of something. Flag A piece of cloth used as a decoration or to represent a country or symbol. Tower Net A 2D flat shape, that can become a 3D shape once assembled. Gatehouse Recyclable Material or an object that, when no longer wanted or needed, can be made into something else new. Curtain wall Turret Scoring Scratching a line with a sharp object into card to make the card easier to bend. Stable Object does not easily topple over. Drawbridge Strong It doesn't break easily. Moat Structure Something which stands, usually on its own. Tab The small tabs on the net template that are bent and glued down to hold the shape together. Did you know? Weak It breaks easily. Windsor Castle is the largest castle in Basic England. -

Gloucestershire Castles

Gloucestershire Archives Take One Castle Gloucestershire Castles The first castles in Gloucestershire were built soon after the Norman invasion of 1066. After the Battle of Hastings, the Normans had an urgent need to consolidate the land they had conquered and at the same time provide a secure political and military base to control the country. Castles were an ideal way to do this as not only did they secure newly won lands in military terms (acting as bases for troops and supply bases), they also served as a visible reminder to the local population of the ever-present power and threat of force of their new overlords. Early castles were usually one of three types; a ringwork, a motte or a motte & bailey; A Ringwork was a simple oval or circular earthwork formed of a ditch and bank. A motte was an artificially raised earthwork (made by piling up turf and soil) with a flat top on which was built a wooden tower or ‘keep’ and a protective palisade. A motte & bailey was a combination of a motte with a bailey or walled enclosure that usually but not always enclosed the motte. The keep was the strongest and securest part of a castle and was usually the main place of residence of the lord of the castle, although this changed over time. The name has a complex origin and stems from the Middle English term ‘kype’, meaning basket or cask, after the structure of the early keeps (which resembled tubes). The name ‘keep’ was only used from the 1500s onwards and the contemporary medieval term was ‘donjon’ (an apparent French corruption of the Latin dominarium) although turris, turris castri or magna turris (tower, castle tower and great tower respectively) were also used. -

Great Chalfield, Wiltshire: Archaeology and History (Notes for Visitors, Prepared by the Royal Archaeological Institute, 2017)

Great Chalfield, Wiltshire: archaeology and history (notes for visitors, prepared by the Royal Archaeological Institute, 2017) Great Chalfield manor belonged to a branch of the Percy family in the Middle Ages. One of them probably had the moat dug and the internal stone wall, of which a part survives, built, possibly in the thirteenth century. Its bastions have the remains of arrow-slits, unless those are later romanticizing features. The site would have been defensible, though without a strong tower could hardly have been regarded as a castle; the Percy house was a courtyard, with a tower attached to one range, but its diameter is too small for that to have been much more than a staircase turret. The house went through various owners and other vicissitudes, but was rescued by a Wiltshire business-man, who employed W. H. Brakspear as architect (see Paul Jack’s contribution, below). It is now owned by the National Trust (plan reproduced with permission of NT Images). Security rather than impregnability is likely to have been the intention of Thomas Tropenell, the builder of most of the surviving house. He was a local man and a lawyer who acquired the estate seemingly on a lease, and subsequently and after much litigation by purchase, during the late 1420s/60s (Driver 2000). In the house is the large and impressive cartulary that documents these struggles, which are typical of the inter- and intra-family feuding that characterized the fifteenth century, even below the level of royal battles and hollow crowns. Tropenell was adviser to Lord Hungerford, the dominant local baron; he was not therefore going to build anything that looked like a castle to challenge nearby Farleigh. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

The Construction of Northumberland House and the Patronage of Its Original Builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1603–14

The Antiquaries Journal, 90, 2010,pp1 of 60 r The Society of Antiquaries of London, 2010 doi:10.1017⁄s0003581510000016 THE CONSTRUCTION OF NORTHUMBERLAND HOUSE AND THE PATRONAGE OF ITS ORIGINAL BUILDER, LORD HENRY HOWARD, 1603–14 Manolo Guerci Manolo Guerci, Kent School of Architecture, University of Kent, Marlowe Building, Canterbury CT27NR, UK. E-mail: [email protected] This paper affords a complete analysis of the construction of the original Northampton (later Northumberland) House in the Strand (demolished in 1874), which has never been fully investigated. It begins with an examination of the little-known architectural patronage of its builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton from 1603, one of the most interesting figures of the early Stuart era. With reference to the building of the contemporary Salisbury House by Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the only other Strand palace to be built in the early seventeenth century, textual and visual evidence are closely investigated. A rediscovered eleva- tional drawing of the original front of Northampton House is also discussed. By associating it with other sources, such as the first inventory of the house (transcribed in the Appendix), the inside and outside of Northampton House as Henry Howard left it in 1614 are re-configured for the first time. Northumberland House was the greatest representative of the old aristocratic mansions on the Strand – the almost uninterrupted series of waterfront palaces and large gardens that stretched from Westminster to the City of London, the political and economic centres of the country, respectively. Northumberland House was also the only one to have survived into the age of photography. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Research Issues1 Wybrane Zespoły Bramne Na Śląsku

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS 3/2019 ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING DOI: 10.4467/2353737XCT.19.032.10206 SUBMISSION OF THE FINAL VERSION: 15/02/2019 Andrzej Legendziewicz orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-296X [email protected] Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Technology Selected city gates in Silesia – research issues1 Wybrane zespoły bramne na Śląsku – problematyka badawcza Abstract1 The conservation work performed on the city gates of some Silesian cities in recent years has offered the opportunity to undertake architectural research. The researchers’ interest was particularly aroused by towers which form the framing of entrances to old-town areas and which are also a reflection of the ambitious aspirations and changing tastes of townspeople and a result of the evolution of architectural forms. Some of the gate buildings were demolished in the 19th century as a result of city development. This article presents the results of research into selected city gates: Grobnicka Gate in Głubczyce, Górna Gate in Głuchołazy, Lewińska Gate in Grodków, Krakowska and Wrocławska Gates in Namysłów, and Dolna Gate in Prudnik. The obtained research material supported an attempt to verify the propositions published in literature concerning the evolution of military buildings in Silesia between the 14th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Relicts of objects that have not survived were identified in two cases. Keywords: Silesia, architecture, city walls, Gothic, the Renaissance Streszczenie Prace konserwatorskie prowadzone na bramach w niektórych miastach Śląska w ostatnich latach były okazją do przeprowadzenia badań architektonicznych. Zainteresowanie badaczy budziły zwłaszcza wieże, które tworzyły wejścia na obszary staromiejskie, a także były obrazem ambitnych aspiracji i zmieniających się gustów mieszczan oraz rezultatem ewolucji form architektonicznych.