Why the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How David Kelly of the Golden State Warriors Serves the Winning Team

Order in the Court: How David Kelly of the Golden State Warriors Serves the Winning Team Skills and Professional Development 1 / 7 As the general counsel of the Golden State Warriors, one of the NBA's best basketball teams, David Kelly lives the life of at least five different general counsel. He serves as a basketball lawyer, startup lawyer, consumer lawyer, real estate lawyer, and media lawyer. That is how the humble and multitalented Kelly oversees the legal needs of Golden State Warriors, an organization that is constantly in the public eye. Just like his team, he brings a focus on excellence and an easy grace, no matter what each day brings him. GC of a basketball team: When Joe Lacob and Peter Guber started looking for a general counsel in 2012 for the team they purchased at the end of 2010, David Kelly jumped at the opportunity. He had just made partner at Katten Muchin Rosenman, a well known Chicago sports and entertainment law firm, and he had done corporate work for various sports teams, including working as outside counsel for Lacob on Guber on their purchase of the team. Kelly explained, "I have always had a passion for the sports and entertainment industries and I had my eye on going in-house in one industry or the other. When I heard Lacob and Guber were going to hire a GC, I knew it would be my dream job. The Warriors were struggling as a franchise at the time, but I knew Lacob and Guber had the tools and a plan – and Stephen Curry – and would turn things around. -

How the Golden State Warriors Have Hyper-Commercialized Professional Sports

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2019 A “Steph” in The Process: How The Golden State Warriors Have Hyper-Commercialized Professional Sports Danielle Arena Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Arena, Danielle, "A “Steph” in The Process: How The Golden State Warriors Have Hyper- Commercialized Professional Sports" (2019). Senior Theses. 119. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arena 1 Dominican University of California A “Steph” in The Process: How The Golden State Warriors Have Hyper-Commercialized Professional Sports A Senior Capstone Submitted to The Faculty of the Division of Public Affairs In Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History Department of History By Danielle Arena Arena 2 Abstract This research aims to highlight the significant impact the Golden State Warriors have had on the commercialization of sports. This is especially relevant and corresponds to the Warriors back-to-back championships and their rise from an overlooked team to one of the most popular teams in the National Basketball League (NBA). According to Forbes, the Warriors have gone from NBA obscurity to the third most valuable team in the NBA. The objective of this research is to prove the importance of both physical prowess and business savvy in the sports world to become truly successful as a professional franchise. -

25 WNBA Facts

25 WNBA Facts Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts In celebration of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) 25th Season, Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast has developed 25 WNBA Facts for educational purposes. WNBA began its first season on June 21, 1997. 1 The first eight WNBA franchises were located in 2 cities with NBA teams. Currently, there are 12 WNBA teams: six in the eastern conference and 3 six in the western Sheryl Swoopes was the conference. first player signed to the 4 WNBA. Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts The eight teams with the best regular season record qualify for the 5 postseason. Houston Comets (defunct) won the first four WNBA 6 titles: (1997, 1998, 1999, 2000). The 3-point line is 22 feet, 1.75 inches. 7 Cynthia Cooper is the only player in WNBA 8 history to win back-to-back WNBA MVP awards. Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts The Houston Comets (defunct), the Minnesota Lynx, and the Seattle 9 Storm are tied with the most championship wins In its inaugural season, (4) in league history. WNBA attendance 10 exceeded one million fans. The tallest player is Margo Dydek (deceased). She was 7 feet, 2 inches. 11 Sue Bird became the first player in WNBA history to 12 win a championship in three different decades (2004, 2010, 2018, 2020). Copyright (c) 2021 Black Girls Talk Sports Podcast 25 WNBA Facts WNBA's regulation ball is 28.5 inches in circumference and one 13 inch smaller than the NBA’s regulation ball. -

Playoff Individual Superlatives

2020 WNBA Playoffs Individual Single-Game Superlatives (Final) Points Rebounds Assists Pts Player, Team Date Reb Player, Team Date Ast Player, Team Date 37 Breanna Stewart, Sea. Oct 2 15 Breanna Stewart, Sea. Oct 2 16 Sue Bird, Sea. Oct 2 31 Breanna Stewart, Sea. Sep 27 15 DeWanna Bonner, Con. Sep 27 10 Danielle Robinson, L.V. Oct 4 31 Jasmine Thomas, Con. Sep 20 15 Napheesa Collier, Min. Sep 27 10 Sue Bird, Sea. Oct 4 29 Angel McCoughtry, L.V. Sep 27 14 Brianna Turner, Pho. Sep 17 9 Sue Bird, Sea. Sep 27 29 A'ja Wilson, L.V. Sep 22 14 Candace Parker, L.A. Sep 17 9 Diana Taurasi, Pho. Sep 17 28 Jewell Loyd, Sea. Oct 2 13 A'ja Wilson, L.V. Sep 27 8 Sue Bird, Sea. Sep 22 28 Diana Taurasi, Pho. Sep 17 13 DeWanna Bonner, Con. Sep 17 8 Alyssa Thomas, Con. Sep 15 28 Alyssa Thomas, Con. Sep 15 13 Alyssa Thomas, Con. Sep 15 26 Breanna Stewart, Sea. Oct 6 Steals Blocks Turnovers Stl Player, Team Date Blk Player, Team Date TO Player, Team Date 5 DeWanna Bonner, Con. Sep 29 7 A'ja Wilson, L.V. Sep 22 6 Alyssa Thomas, Con. Sep 29 5 Alyssa Thomas, Con. Sep 20 6 Napheesa Collier, Min. Sep 22 6 DeWanna Bonner, Con. Sep 22 4 Brionna Jones, Con. Sep 29 4 Breanna Stewart, Sea. Oct 2 5 Lindsay Allen, L.V. Oct 6 4 Damiris Dantas, Min. Sep 22 4 Brianna Turner, Pho. Sep 15 5 Angel McCoughtry, L.V. -

Coaches Handbook

City of Buckeye COMMUNITY SERVICES DEPARTMENT -Recreation Division- COACHES HANDBOOK Important dates Opening day: Saturday, June 16th Picture day: Tuesday, June 19th and Thursday, June 21st Last day: Saturday, July 28th Peter Piper pizza party nights: TBD Community Services Department’s Vision and Mission Statement Our Vision “Buckeye Is An Active, Engaged and Vibrant Community.” Our Mission We are dedicated to enriching quality of life, managing natural resources and creating memorable experiences for all generations. .We do this by: Developing quality parks, diverse programs and sustainable practices. Promoting volunteerism and lifelong learning. Cultivating community events, tourism and economic development. Preserving cultural, natural and historic resources. Offering programs that inspire personal growth, healthy lifestyles and sense of community. Dear Coach: Thank you for volunteering to coach with the City of Buckeye Youth Sports Program. The role of a youth sports coach can be very rewarding, but can be challenging at times as well. We have included helpful information in this handbook to assist in making this an enjoyable season for you and your team. Our youth sports philosophy is to provide our youth with a positive athletic experience in a safe environment where fun, skill development, teamwork, and sportsmanship lay its foundation. In addition, our youth sports programs is designed to encourage maximum participation by all team members; their development is far more important than the outcome of the game. Please be sure to remember you are dealing with children, in a child’s game, where the best motivation of all is enthusiasm, positive reinforcement and team success. If the experience is fun for you, it will also be fun for the kids on your team as well as their parents. -

Notre Dame Athletics

NOTRE DAME Women’s Basketball 2008-09 2001 NCAA Champions • 1997 NCAA Final Four 7 NCAA Sweet 16 Berths • 15 NCAA Tourney Appearances 2008-09 Schedule 2008-09 ND Women’s Basketball: Game 6 5-0 / 0-0 BIG EAST #11/10 Notre Dame Fighting Irish (5-0 / 0-0 BIG EAST) vs. N5 Gannon (exhibition) W, 96-30 Eastern Michigan Eagles (2-4 / 0-0 Mid-American) N16 (16/14) @ LSU (24/22)1-ESPN2 W, 62-53 uDATE: December 2, 2008 uRADIO: Pulse FM (96.9/92.1) N19 (15/15) Evansville W, 96-61 uTIME: 7:00 p.m. ET UND.com N23 (15/15) @ Boston College W, 102-54 uAT: Ypsilanti, Mich. Bob Nagle, p-b-p N25 (14/10) Georgia Southern W, 85-36 Convocation Center (8,824) uLIVE STATS: emueagles.com N29 Michigan State 2:00 ET uSERIES: ND leads 2-0 uTEXT ALERT: UND.com u1ST MTG: ND 75-58 (12/15/82) uTICKETS: (734) 487-2282 D2 @ Eastern Michigan 7:00 ET uLAST MTG: ND 70-59 (11/30/84) D7 Purdue 2:00 ET D10 @ MichiganBTN 7:00 ET Storylines Web Sites D13 @ Valparaiso 1:35 CT u Notre Dame will take on Eastern Michigan u Notre Dame: http://www.UND.com D20 Loyola-Chicago 2:00 ET for the first time in more than 24 years, with u Eastern Michigan: http://www.emueagles.com D28 @ CharlotteESPNU 2:00 ET the Eagles being the lone MAC opponent on u BIG EAST: http://www.bigeast.org D30 @ Vanderbilt 7:00 CT this year’s Irish schedule. -

The Fundamentals of Shooting the Basketball

The Fundamentals of Shooting the Basketball The objective of the offense in Basketball is accuracy of each attempted shot. Most players recognize this; but, only the better shooters learn how to practice correctly and work at improvement year round. Since most of this practice sessions are alone, every player must be his own critic. This means he\she must understand the proper mechanics that affect the success, or failure, of every shot. Every player must know his range and know what is a good shot. Therefore, before examining the techniques associated with the various shots, a good basketball player is expected to have in his arsenal, here are the principles at work in every scoring shot from anywhere on a basketball court. These are divided into two parts, the mental aspect and the physical aspect: 1. Mental. At no time is psychological conditioning more critical than when shooting the basketball in a game. Knowing when to shoot and being able to do it effectively under pressure distinguishes the great shooter from the ordinary. Regardless of how much he practices, or how well he conditions himself, only a modest amount of improvement is possible in speed, reflexes, or strength. History gives many examples of players able to achieve greatness despite mediocre physical talent. Usually, however, such successes are due to determination. a. Concentration: is the fixing of attention on the job at hand and is characteristic of every great athlete. Through continuous practice, good shooters develop their concentration to the extent that they are oblivious to every distraction. Ability to relax: is closely related to concentration. -

Apartment Insider LAS VEGAS MULTIFAMILYJULY 2017 MARKET REPORT

Apartment Insider LAS VEGAS MULTIFAMILYJULY 2017 MARKET REPORT ISSUE 21 | 2019 CONTENTS FEATURED LISTING - 01 ECHELON AT CENTENNIAL HILLS IS VEGAS THE SPORTS 03 CAPITAL OF THE WORLD? Q1-19 MULTIFAMILY 11 MARKET RECAP CARL SIMS TAYLOR SIMS Executive Director Director Direct: +1 702 688 6921 Direct: +1 702 688 6957 [email protected] [email protected] FEATURED LISTING Echelon at Centennial Hills Courtyard Clubhouse Pool / Spa Dog Park Gym Inside Parking 62 2008 UNITS BUILT 9501 ECHELON POINT DRIVE, LAS VEGAS, NV 89149 CONTACT: Taylor Sims | Director | +1 702 688 6957 | [email protected] 1 2 IS LAS VEGAS BECOMING THE SPORTS CAPITAL OF THE WORLD? Only a few years ago all that Las Vegas had to offer in sports was the occasional people) dedicated to the hospitality sector. Visitor growth (in both volume and spending) championship boxing match. How things have changed in just a few years. Today we continues to rise month over month, and the industry is healthy with many companies have hockey, football, baseball, soccer, basketball, national rodeo finals, & racing events. competing to add new workers. 2018 visitor volume was over 42M and trending strong. Southern Nevada continues its long winning streak. The activity surrounding sports is Visitors are seeking entertainment and Southern Nevada continues to diversify by focusing fruitful for the market’s main export, tourism, with 30% of the area’s work force (nearly 400k on sports. Let’s take a look at the current & upcoming sports that call Vegas home. 3 - Taylor Sims 4 HOCKEY FOOTBALL LAS VEGAS GOLDEN KNIGHTS LAS VEGAS RAIDERS A unicorn inaugural season was demonstrated While the franchise has 50 years under its belt, the infrastructure in Las Vegas is literally with flare and [Marc-André] Fleury when the and figuratively getting placed. -

Remarks Honoring the 2000 Women's National Basketball Association Champion Houston Comets May 14, 2001

Administration of George W. Bush, 2001 / May 14 749 details have caused too many families to bury NOTE: The President spoke at 11:32 a.m. at the the next generation. And for all our children’s Pennsylvania Convention Center. In his remarks, sake, this Nation must reclaim our neighbor- he referred to Mayor John F. Street of Philadel- hoods and our streets. phia; and Gov. Tom Ridge, Lt. Gov. Mark S. Schweiker, and Attorney General Mike Fisher of We need a national strategy to assure that Pennsylvania. every community is attacking gun violence with focus and intensity. I’m here today to announce a national initiative to help cities Remarks Honoring the 2000 like Philadelphia fight gun violence. The pro- Women’s National Basketball gram I propose, we call Project Safe Neigh- Association Champion Houston borhoods, will establish a network of law en- Comets forcement and community initiatives tar- May 14, 2001 geted at gun violence. It will involve an un- precedented partnership between all levels Well, thank you all for coming. It’s my of government. It will increase accountability honor to welcome the first Texas team to the within our systems. And it will send an un- White House since I’ve been fortunate mistakable message: If you use a gun illegally, enough to be the President. It seems like it’s you will do hard time. becoming quite a habit. This Nation must enforce the gun laws Thank you very much, Nancy, for coming. which exist on the books. Project Safe Neigh- It’s my honor to welcome two Texas Con- borhoods incorporates and builds upon the gressmen: Ken Bentsen and John Culberson. -

The History of Arizona Women's Basketball

All-Time Series Records Series First Last Last Series First Last Last Opponent Record Meeting Meeting Result Opponent Record Meeting Meeting Result Alabama 0-1 11/29/87 11/29/87 L 74-80 Northern Illinois 2-1 12/22/92 12/15/99 W 78-46 American 0-0 12/6/03 Northwestern 1-0 3/23/96 3/23/96 W 79-63 Arizona State 28-36 2/2/73 2/22/03 W 72-52 Notre Dame 1-3 12/3/88 3/23/03 L 47-59 Arkansas 1-0 3/22/96 3/22/96 W 80-77 Oakland 2-0 12/29/88 12/29/89 W 75-65 Auburn 0-1 12/19/00 12/19/00 L 66-69 Ohio State 1-1 11/21/01 12/15/02 L 65-84 Baylor 2-0 12/22/81 12/29/97 W 86-73 Oklahoma 1-0 11/19/99 11/19/99 W 75-59 Biola 1-1 12/9/78 1/27/83 W 82-47 Oklahoma State 0-2 12/3/81 12/4/94 L 40-64 Boston College 0-1 12/30/87 12/30/87 L 64-79 Old Dominion 0-2 1/7/86 1/4/88 L 68-82 Bowling Green 1-0 12/8/00 12/8/00 W 99-43 Oregon 14-22 1/3/81 2/1/03 W 71-66 Brigham Young 3-5 2/24/73 11/18/00 W 76-71 Oregon State 18-19 12/7/83 3/8/03 W 70-56 California 25-13 12/17/77 3/1/03 W 68-51 Pacific 1-2 11/21/81 1/4/84 L 79-84 UC Irvine 3-3 12/14/81 11/28/93 W 73-67 Pacific Christian 1-0 12/10/81 12/10/81 W 84-60 UC Riverside 1-0 12/7/02 12/7/02 W 95-66 Pepperdine 5-2 12/29/82 11/25/02 W 80-68 UC Santa Barbara 6-4 1/3/80 1/14/02 L 80-94 Pittsburgh 0-1 12/2/01 12/2/01 L 80-81 Cal Poly-Pomona 0-6 11/19/77 11/20/82 L 66-74 Portland State 3-2 12/18/83 11/30/91 L 76-85 Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo 1-0 1/9/96 1/9/96 W 75-39 Providence 2-0 12/29/92 12/30/95 W 97-83 Cal State Fullerton 5-9 1/10/80 12/8/95 W 87-33 Puerto Rico-Mayaguez 1-0 12/20/00 12/20/00 W 105-41 Cal State Northridge 2-1 12/1/78 2/16/94 W 98-57 Purdue 0-2 12/20/97 11/19/98 L 58-65 Chico State 1-0 12/7/79 12/7/79 W 64-61 Rice 2-0 11/28/00 12/8/01 W 74-65 Cleveland State 0-1 11/28/82 11/28/82 L 43-61 Rutgers 0-2 1/2/88 3/14/99 L 47-90 Colorado 3-5 2/21/75 11/24/91 L 53-77 Sacramento State 1-0 12/17/94 12/17/94 W 105-50 Colorado State 6-2 2/22/75 12/6/99 W 89-75 St. -

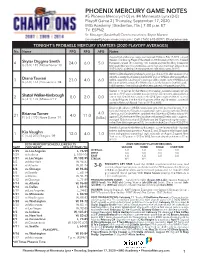

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) Vs

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) vs. #4 Minnesota Lynx (0-0) Playoff Game 2 | Thursday, September 17, 2020 IMG Academy | Bradenton, Fla. | 7:00 p.m. ET TV: ESPN2 Sr. Manager, Basketball Communications: Bryce Marsee [email protected] | Cell: (765) 618-0897 | @brycemarsee TONIGHT'S PROBABLE MERCURY STARTERS (2020 PLAYOFF AVERAGES) No. Name PPG RPG APG Notes Aquired by the Mercury in a sign-and-trade with Dallas on Feb. 12, 2020...named Western Conference Player of the Week on 9/8 for week of 8/31-9/6...finished 4 Skylar Diggins-Smith 24.0 6.0 5.0 the season ranked 7th in scoring, 10th in assists and tied for 4th in three-point G | 5-9 | 145 | Notre Dame '13 field goals (46)...scored a postseason career-high and team-high 24 points on 9/15 vs. WAS...picked up her first playoffs win over Washington on 9/15 WNBA's all-time leader in postseason scoring and ranks 3rd in all-time assists in the playoffs...6 assists shy of passing Sue Bird for 2nd on WNBA's all-time playoffs as- 3 Diana Taurasi 23.0 4.0 6.0 sists list...ranked 5th in the league in scoring and 8th in assists...led the WNBA in 3-pt G | 6-0 | 163 | Connecticut '04 field goals (61) this season, the 11th time she's led the league in 3-pt field goals... holds a perfect 7-0 record in single elimination games in the playoffs since 2016 Started in 10 games for the Mercury this season..scored a career-high 24 points on 9/11 against Seattle in a career-high 35 mimutes...also posted a 2 Shatori Walker-Kimbrough 8.0 2.0 0.0 career-high 5 steals this season in the 8/14 game against Atlanta...scored G | 6-1 | 170 | Missouri '19 in double figures 5 of the final 8 games of the regular season...scored 8 points in Mercury's Round 1 win on 9/15 vs. -

LSU Women's Basketball LSU Combined Team Statistics (As of Nov 26, 2007) All Games

2007-008 LSU WOMEN’S BASKETBALL TONIGHT’S GAME QUICK FACTS LSU head coach: Van Chancellor Game #7 Chancellor’s career record: 443-156 (20th year) Chancellor’s LSU record: 4-2 (1st year) (4-2, 0-0 SEC) Houston Itm. head coach: Danny Hughes LSU Lady Tigers School record: 2-5 (1st year) No. 8 AP/No. 7 Coaches Career record: 2-5 (1st year) at Series record: LSU leads 4-3 Last meeting: LSU defeated Houston, 88-44, on Nov. 28, 1998 in Baton Rouge. Houston Cougars (2-5, 0-0 C-USA) Television: none Satellite feed: None NR AP/NR Coaches Radio: LSU Sports Radio Network (Patrick Wright & Brian Miller) Nov. 29, 2007 • Hofheinz Pavilion (8,479) Officials: Jeff Caudle, Gator Parrish, David Houston, Texas • 7 p.m. CST Kramer LSU Sports Information: Brian Miller LADY TIGERS’ PROBABLE STARTERS C: 225-939-0204 E-mail: [email protected] G 5 Erica White 5-3 Sr. 4.8 ppg 1.6 rpg 3.0 apg Houston Sports Information: Ryan Koslen • Has started 61 games in her career C: 713-598-8666 E-mail: [email protected] G 12 RaShonta LeBlanc 5-7 Sr. 6.2 ppg 4.5 rpg 2.7 spg • Has started 60 games in her career G 15 Quianna Chaney 5-11 Sr. 16.7 ppg 2.8 rpg 3.0 apg • Has started 44 games in her career SCHEDULE/RESULTS F 54 Ashley Thomas 6-0 Sr. 2.5 ppg 3.3 rpg 1.5 spg • Has started 61 games in her career OCTOBER C 34 Sylvia Fowles 6-6 Sr.