The Token and Atlantic Souvenir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

The Spirit of Cleavage: Pedagogy, Gender, and Reform In

THE SPIRIT OF CLEAVAGE: PEDAGOGY, GENDER, AND REFORM IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH WOMEN'S FICTION A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon BY Lisa M. Robson November 1997 O Copyright Lisa M. Robson. 1997. All rights reserved. National Library BiblioWque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellingtort OttawaON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la foxme de rnicrofiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts &om it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent Btre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Permission To Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freeIy available for inspection. -

Loving Thy Neighbor Immigration Reform and Communities of Faith

WASHINGTON PILGRIMAGE Loving Thy Neighbor Immigration Reform and Communities of Faith Sam Fulwood III September 2009 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Loving Thy Neighbor Immigration Reform and Communities of Faith Sam Fulwood III September 2009 And if a stranger sojourn with thee in your land, ye shall not vex him. But the stranger that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God Leviticus 19:33-34 Introduction and summary As a fresh immigration reform debate gears up in Washington, D.C., a wide range of faith groups are showing a new, unexpected, and grassroots-led social activism that’s rooted in theological and moral ground. While loud and shrill anti-immigrant voices dominate much of the media attention regarding immigrants and especially the undocumented faith com- munity activists are caring and praying in the shadows of public attention. These groups have worked for many years and across the country on immigration issues and as strong advocates for undocumented workers and their families. Their efforts include creating citizenship projects, offering educational and support services, fighting discrimination and exploitation, bridging gaps between immigrant and nonimmigrant communities, providing sanctuary for immigrant families, supporting comprehensive legislative reform, and more. Hundreds of diverse faith communities have been active independently and within larger organizations. Mainline Protestant denominations, Catholic parishes, Jewish congrega- tions, and others, along with groups such as PICO, the Interfaith Immigration Coalition, Sojourners, Catholic Social Services, Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, Families United, and Gamaliel have stood up and spoken out on behalf of immigrants and their families. -

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE Zobrazení Etnicity a Rasy Ve

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH VĚD Institut komunikačních studií a žurnalistiky Tereza Barešová Zobrazení etnicity a rasy ve vybraných science fiction seriálech Diplomová práce Praha 2015 Autor práce: Tereza Barešová Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Iva Baslarová, Ph.D. Datum obhajoby: 2015 Bibliografický záznam Barešová, Tereza. Zobrazení etnicity a rasy ve vybraných science fiction seriálech. Praha, 2015. 72 s. Diplomová práce (Mgr.) Univerzita Karlova, Fakulta sociálních věd, Institut komunikačních studií a žurnalistiky. Katedra mediálních studií. Vedoucí diplomové práce Mgr. Iva Baslarová, Ph.D. Anotace (abstrakt) Tato diplomová práce se věnuje zobrazením etnicity a rasy „ne-lidí“ v prvních dvou řadách science fiction seriálů Star Trek: The Next Generation, Battlestar Galactica a Defiance. Vychází při tom z postkolonialistické teorie, která se zabývá dominantním vztahem kolonizátorů ke kolonizovaným. Ten se vytvořil mezi lidmi ze západní společnosti při osidlování nově objevených území a domorodým obyvatelstvem. V případě science fiction jsou „ne-lidé“ v pozici kolonizovaných a lidé kolonizátory. Prostor je také věnován posthumanistické teorii, která představuje vizi bytosti založené na kombinaci biologických a mechanických částí. Vybrané seriály jsou zkoumány pomocí metody kvalitativní obsahové analýzy. Ukázalo se, že lidé jsou ve science fiction seriálech rasou, od které se odvíjí zobrazování všech ostatních „ne-lidských“ ras. Lidé jsou také ve většině případů jiným rasám nadřazeni, což se projevuje mnoha způsoby. Hodnoty, které uznává dnešní západní společnost, jsou prezentovány jako hodnoty celé lidské rasy. Od nich se odvíjí i vnímání „ne-lidí“ a jejich společností. Ve science fiction se také odrážejí problémy, které měla západní společnost v době jejich vzniku. Abstract The main focus of this diploma thesis is picturing ethnicity and race of “non- humans” in first two series of science fiction series Star Trek: The Next Generation, Battlestar Galactica a Defiance. -

The Little Minister

The Little Minister J.M. Barrie The Little Minister Table of Contents The Little Minister....................................................................................................................................................1 J.M. Barrie......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. THE LOVE−LIGHT...............................................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. RUNS ALONGSIDE THE MAKING OF A MINISTER.....................................................4 CHAPTER III. THE NIGHT−WATCHERS.................................................................................................8 CHAPTER IV. FIRST COMING OF THE EGYPTIAN WOMAN...........................................................14 CHAPTER V. A WARLIKE CHAPTER, CULMINATING IN THE FLOUTING OF THE MINISTER BY THE WOMAN.................................................................................................................19 CHAPTER VI. IN WHICH THE SOLDIERS MEET THE AMAZONS OF THRUMS...........................25 CHAPTER VII. HAS THE FOLLY OF LOOKING INTO A WOMAN'S EYES BY WAY OF TEXT..........................................................................................................................................................32 CHAPTER VIII. 3 A.M.MONSTROUS AUDACITY OF THE WOMAN.............................................37 CHAPTER IX. THE WOMAN CONSIDERED IN ABSENCEADVENTURES OF -

Northwoods Heritage Fest

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 only POSTAL PATRON POSTAL 499 GIBSON $ Hwy. 45 S., Eagle River Saturday, Saturday, June 6, 2015 6, June only (715) 479-4421 599 $ AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS ASTOR only northwoodsfurniture.com Store Hours: Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Sun. 11 a.m. - 3 p.m. Store Hours: Mon.-Sat. 9 a.m. - 5 p.m., Sun. 11 399 715-477-2573 FREE LOCAL • DELIVERY FREE REMOVAL $ A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A CONNER NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL ALL RECLINERS ARE NOT CREATED EQUAL CREATED ARE NOT RECLINERS ALL © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 Inc. Publications, NORTHWOODS HERITAGE FEST SUNDAY, JUNE 14, 2015 11:00 am - 9:00 pm Cy Williams Park, 1704 Superior Street, Three Lakes LIVE ENTERTAINMENT IN THE INTERNATIONAL BEER GARDEN “Parade of Flags” • International Beer & Wine Garden • Sprecher Fire 11:30 am – 1:30 pm BRET & FRISK Trucks • Three Lakes Tavern League “Bean Bag Competition” • Three • 1:30 pm – 2:00 pm PARADE OF FLAGS & NATIONAL ANTHEMS Lakes Fire Dept. Auxiliary “Cakewalk” “Find Your Heritage” with Three Lakes Genealogical Society • NATH - Northwoods Alliance for 2:30 pm – 5:00 pm DIAMOND PEPPER “Songs of Neil Diamond” Temporary Housing • Three Lakes Historical Society Exhibit • Nicolet 5:00 pm – 6:00 pm KINSELLA IRISH DANCERS Bird Club of Three Lakes • Face painting by Festive Faces • Playground 6:00 pm – 9:00 pm BIG ROAD in the park for the children • Free Admission “DIAMOND” PEPPER BRET & FRISK “Songs of Neil Diamond” Featuring German, Polish, Italian & Wisconsin, USA cuisines GERMAN MENU Beef Rouladen - Bacon & Onion rolled in Top Sirloin (no pickle) served with Spaetzle, Rich brown gravy & red cabbage. -

All Remaining Docks & Lifts

NORTH WOODS A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW POSTAL PATRON AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS PRSRT STD 1651 Hwy. 45North,Eagle River 1651 Hwy. Labor DayWeekendSale Labor DayWeekendSale ECRWSS • Boatwinterizing&storage U.S. Postage PAID ALL REMAININGDOCKS &LIFTS Saturday, Permit No. 13 Eagle River www.tracksideinc.com Aug. 23, 2014 TRACK SIDE & POLARIS ARE DONATING $20 FOR EACH RIDE OF AN ATV, RANGER,RZROR RIDEOFANATV, $20FOREACH SIDE&POLARISAREDONATING TRACK JOIN US SATURDAY, AUG. 30, 9 A.M. TO 3P.M. 30,9A.M.TO AUG. JOIN USSATURDAY, SALES SERVICE RENTALS SALES SERVICE Friday, Aug. 29 thru Monday, Sept.1 Aug. 29thruMonday, Friday, (715) 479-4421 Fundraiser for Youth Hockey @ Eagle River Ice Arena, Highway70East Hockey@EagleRiverIce Youth Fundraiser for © Eagle River Publications, Inc. 1972 THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING of Eagle River • We arestatelicensed&bonded • We ParsonsParsons 715-479-2200 50% off 50% off • Indoorcold&heatedoroutdoorstorageavailable snowmobiles Labor Day Hours: on display & clothing Open Friday, Aug. 29 8 a.m. - 6 p.m. Closed Saturday-Monday 2015 now Open Tuesday, Sept. 2 8 a.m.-6 p.m. ACE 437 W. DivisionSt., EagleRiver 437 W. 2015 Chevy Silverado 2014 Chevy Silverado 1500 Crew Cab www.eaglerivermarine.com 2014 Chevy Impala LT 2500 Reg. Cab Utility Body Upfit LT, All Star Edition Package, 2.5L Engine, Backup Camera, 18" Tires, LED Cargo Lights Remote Start Brand FX Utility Body, 6.0L V8, Power Windows & Locks, 17" All-Terrain Tires MSRP $43,135 MSRP $30,860 Stk #2136 Stk #6324 MSRP $45,769 Labor -

Wives and Widows Or the Broken Life by Ann S

Wives and Widows Or The Broken Life By Ann S. Stephens WIVES AND WIDOWS. CHAPTER I. LEAVING MY HOME. At ten years of age I was the unconscious mistress of a heavy stone farm- house and extensive lands in the interior of Pennsylvania, with railroad- bonds and bank-stock enough to secure me a moderate independence. I shall never, never forget the loneliness of that old house the day my mother was carried out of it and laid down by her husband in the churchyard behind the village. The most intense suffering of life often comes in childhood. My mother was dead; I could almost feel her last cold kisses on my lip as I sat down in that desolate parlor, waiting for the guardian who was expected to take me from my dear old home to his. The window opened into a field of white clover, where some cows and lambs were pasturing drowsily, as I had seen them a hundred times; but now their very tranquillity grieved me. It seemed strange that they would stand there so content, with the white clover dropping from their mouths, and I going away forever. My mother's canary-bird, which hung in the window, began to sing joyously over my head, as if no funeral had passed from that room, leaving its shadows behind, and, more grievous still, as if it did not care that I might never sit and listen to it again. One of the neighbors had kindly volunteered to take charge of the gloomy old house till my guardian came, but her presence disturbed me more than funereal stillness would have done. -

Robert Lee Goins Recipient of Veterans Service Award Second Annual Recognition Named After Bill Norwood by JOYANNA LOVE Service to Veterans Or Their Families

MONDAY 161st YEAR • NO. 21 MAY 25, 2015 CLEVELAND, TN 22 PAGES • 50¢ Inside Today Robert Lee Goins recipient of veterans service award Second annual recognition named after Bill Norwood By JOYANNA LOVE service to veterans or their families. Goins was recommended by Banner Senior Staff Writer “There was consistent agreement Bradley County Veterans Affairs that this was the best one,” Heidel Director Larry McDaris. The Bill Norwood Service Award was said of the committee’s decision. In a previous interview with the presented to Robert Lee Goins today Heidel said Goins levels the graves, Cleveland Daily Banner, Goins said at Bradley County’s annual Memorial cleans headstones, trims shrubbery, taking care of the Veterans Cemetery Day ceremony on the Courthouse removes old flags and sets the head- was a way to honor the veterans. Plaza. stones. “I do this now because I feel like I Goins was nominated for his 19 Goins’ father is one of many veter- should do something for these guys. Edwards breaks years of volunteer service in caring for ans buried in the fenced-in area of the It’s the least I can do since I didn’t get the veterans area of Fort Hill cemetery designated for local veter- to serve,” Goins said. victory drought Cemetery. ans. Goins had received a draft notice in Banner file photo Carl Edwards drove to Victory Award committee member Cid Cleveland Mayor Tom Rowland also 1968, but was in the hospital recover- ROBERT GOINS, kneeling at his father’s head- Lane for the first time in two sea- Heidel said the recipient was selected recognized Goins for his efforts in stone, has voluntarily cared for the veterans’ sec- sons, with a win in the Coca-Cola based on the type and duration of 2006. -

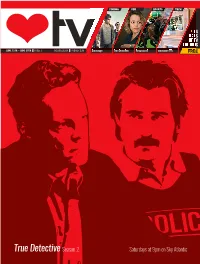

True Detectiveseason 2

CINEMA VOD SPORTS TECH + 14 DAYS OF TV LISTINGS JUNE 15TH – JUNE 28TH ISSUE 3 TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM Entourage True Detective Royal Ascot Innovative TVs FREE True Detective Season 2 Saturdays at 9pm on Sky Atlantic TV Guide Magazine Issue 3 V20.indd 1 12/06/2015 10:13 JUNE 15TH – JUNE 28TH ISSUE 3 Contents TVGUIDE.CO.UK TVDAILY.COM EDITOR’S LETTER 4 News 16 Fashion The times are changing The biggest news from the world of television. Steal the style of the most bad-ass characters in the film industry. In on television. This week’s theme: the races. 2015, film actors at the height of their careers are habitually hopping across to television. Sometime in the last ten years, the 17 Drinks old barren wastelands Drink like the characters of Mad Men with of space between film and television were tips on tipples and local watering holes. developed into a high- speed rail service. No show illustrates this better than True Detective, which Sports returns to our screens on 18 June 22. To celebrate its Race information, quirky facts and hot tips return, we’ve dedicated a feature to the hit on horses for this year’s Royal Ascot. crime-drama (p. 6), and a 6 True Detective second on the intertwining trajectories of film and television (p. 14). Long Transforms TV 21 Youtube may TV reign! How HBO’s True Detective changed television Susan Brett, Editor Our guide to the best gaming channels. for the better when it fi rst aired in 2014. -

Deep Secret Diana Wynne Jones

Deep Secret Diana Wynne Jones A 3S digital back-up edition 1.0 click for scan notes and proofing history Contents |1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9|10|11|12|13|14| |15|16|17|18|19|20|21|22|23|24|25| “I’d vote for Diana Wynne Jones as a British National Treasure.” —Locus “Unusual seriocomic science fantasy.” —Booklist on Dogsbody (An ALA Notable Book) DEEP SECRET All over the Multiverse (the universe that is in the shape of Infinity, like a figure eight laid on its side), the Magids, powerful magicians, are at work to maintain the balance between positive and negative magic for the good of all. They use their magical talents to push people into doing the right thing at the right time. Rupert Venables is the junior Magid assigned to Earth and to the troublesome planets of the Koyrfonic Empire as well. The Empire is situated right at the twist at the center of the Multiverse. There is a problem of succession when the Emperor dies without a known heir, paralleled by a more personal problem on Earth when Rupert’s senior dies and appoints him senior. Now Rupert must search the Earth for an appropriate new Magid, while helping part-time to prevent the descent of the Empire into chaos. And then the problems become intertwined when Rupert finds that he can meet all five of the potential Magids on Earth by attending one SF convention in England. And that other forces, some of them completely out of control, will be there too. -

The Reflections of Ambrosine, by Elinor Glyn 1

The Reflections of Ambrosine, by Elinor Glyn 1 The Reflections of Ambrosine, by Elinor Glyn The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Reflections of Ambrosine, by Elinor Glyn This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Reflections of Ambrosine A Novel Author: Elinor Glyn Release Date: March 18, 2004 [EBook #11624] Language: English The Reflections of Ambrosine, by Elinor Glyn 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE REFLECTIONS OF AMBROSINE *** Produced by Charles Aldarondo, Keren Vergon, William Flis and PG Distributed Proofreaders The Reflections of Ambrosine A Novel by Elinor Glyn NOTE In thanking the readers who were kind enough to appreciate my "Visits of Elizabeth," I take this opportunity of saying that I did not write the two other books which appeared anonymously. The titles of those works were so worded that they gave the public the impression that I was their author. I have never written any book but the "Visits of Elizabeth." Everything that I write will be signed with my name, ELINOR GLYN BOOK I I I have wondered sometimes if there are not perhaps some disadvantages in having really blue blood in one's veins, like grandmamma and me. For instance, if we were ordinary, common people our teeth would chatter naturally with cold when we have to go to bed without fires in our rooms in December; but we pretend we like sleeping in "well-aired rooms"--at least I have to.