From the Hills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Drafting Template

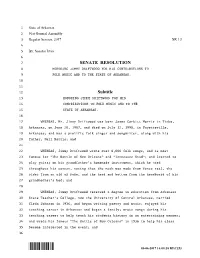

1 State of Arkansas 2 91st General Assembly 3 Regular Session, 2017 SR 13 4 5 By: Senator Irvin 6 7 SENATE RESOLUTION 8 HONORING JIMMY DRIFTWOOD FOR HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO 9 FOLK MUSIC AND TO THE STATE OF ARKANSAS. 10 11 12 Subtitle 13 HONORING JIMMY DRIFTWOOD FOR HIS 14 CONTRIBUTIONS TO FOLK MUSIC AND TO THE 15 STATE OF ARKANSAS. 16 17 WHEREAS, Mr. Jimmy Driftwood was born James Corbitt Morris in Timbo, 18 Arkansas, on June 20, 1907, and died on July 12, 1998, in Fayetteville, 19 Arkansas; and was a prolific folk singer and songwriter, along with his 20 father, Neil Morris; and 21 22 WHEREAS, Jimmy Driftwood wrote over 6,000 folk songs, and is most 23 famous for “The Battle of New Orleans” and “Tennessee Stud“; and learned to 24 play guitar on his grandfather’s homemade instrument, which he used 25 throughout his career, noting that the neck was made from fence rail, the 26 sides from an old ox yoke, and the head and bottom from the headboard of his 27 grandmother’s bed; and 28 29 WHEREAS, Jimmy Driftwood received a degree in education from Arkansas 30 State Teacher’s College, now the University of Central Arkansas, married 31 Cleda Johnson in 1936, and began writing poetry and music; enjoyed his 32 teaching career in Arkansas and began a family; wrote songs during his 33 teaching career to help teach his students history in an entertaining manner; 34 and wrote his famous “The Battle of New Orleans” in 1936 to help his class 35 become interested in the event; and 36 *KLC253* 03-06-2017 14:08:28 KLC253 SR13 1 WHEREAS, it was not until the -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Ryman Auditorium

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-9 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-S OMBNo. 1024-0018 RYMAN AUDITORIUM Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Ryman Auditorium Other Name/Site Number: Union Gospel Tabernacle 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 116 Fifth Avenue North Not for publication:__ City/Town: Nashville Vicinity:__ State: TN County: Davidson Code: 037 Zip Code: 37219 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: _ District: __ Public-State: _ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 ___ buildings ___ sites ___ structures ___ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of related multiple property listing: NPS Form 10-9 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-S OMBNo. 1024-0018 RYMAN AUDITORIUM Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking: or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected]

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS NOVEMBER 25, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Lady A’s Country Artists As Emotionally Torn Ocean Sails >page 4 By Impeachment As Their Fan Base “Old Town” Rode November Lee Greenwood might need to rewrite “God Bless the U.S.A.” in the current climate, and it’s particularly discouraging that Awards Nearly three years into a divisive presidency, the 53rd annual they have a difficult time even settling on reality. >page 10 Country Music Association Awards coincided with the start of “It’s he said/she said,” said LOCASH’s Chris Lucas. “I don’t impeachment hearings on Nov. 13. Judging from the reaction know who to believe or what to believe. There’s two sides, and of the genre’s artists, the opening line in Greenwood’s chorus — the two sides have figured out how to work [the media].” “I’m proud to be an Cash’s father, The Word From American” — is still Johnny Cash, was Garth Brooks a prominent belief. an outspoken sup- >page 11 But “I’m frustrated porter of inclusive to be an American” values, challeng- is hard on its heels as ing the ruling class Still In The Swing: a replacement. in his 1970 single An unscientific “What Is Truth.” Asleep At 50 LOCASH RAY CASH red-carpet poll of Just two years later, >page 11 the creative com- Rosanne cam- munity about the hearings found a wide range of awareness, paigned as a teenager for Democrat George McGovern in his from Rosanne Cash, who said she was “passionate” about bid to unseat Richard Nixon in the White House, and she has Makin’ Tracks: watching them, to a slew of artists who barely knew they were consistently stood up for progressive policies and politicians Tenpenny, Seaforth happening. -

Reflections on Bill Monroe T/Te Mhenian Staff

Page four, THE ATHENIAN, October 1996 30th Annual Fiddlers Reflections on Bill Monroe (cont'd from page one). and around every corner of the campus. Experts and Combined reports by David Robinson, Jim Patterson, novices, friends and strangers, and young and old will and The Music of Bill Monroe MCA join together for jam sessions. Teaching, learning, listening and enjoying will be the order of the day. You Bill Monroe was looking for the men in charge may never even make it to the stages because the jam of WSM radio station. He was ready to take his music sessions provide some of the best entertainment around. from the Carolinas and the east coast, where he had Bring your instrument and join in. beenplaying, to thebroaderaudience that WSM offered. A variety of food will be on sale by Athens State WSM could be heard from the Rocky Mountains to the College clubs and organizations. The convention Atlantic Ocean, but it also had another interesting provides these organizations with the opportunity to draw for Bill Monroe, "WSM has the same initials I raise funds for operating expenses and scholarships. have. That's William Smith Monroe." Arts and crafts will also be available for purchase from He found those men and was hired the same about 150 vendors. Every effort is made to avoid a "flea day. The Grand Ole Opry career that started on market" atmosphere, all vendors are by invitation only October 28, 1939, came to a close just short of fifty- and all exhibits are screened to ensure they are in seven years later on September 9, 1996, when Bill keeping with the traditional music theme. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS NOVEMBER 23, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 18 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Stapleton, Wallen Country By The Glass: The Genre’s Songwriters Reign Page 4 Grapple With Alcohol’s Abundance Bluegrass Turns 75 Country fans might not see all the world through “Whis- so long. Ironically, drinking is one of them.” Page 10 key Glasses,” but they’re definitely hearing it through Getting drunk is such a stereotypical activity in the genre that alcoholic earbuds. it was listed among the elements of the “perfect country and The 2019 Morgan Wallen hit “Whiskey Glasses” brought western song” in David Allan Coe’s “You Never Even Called Me songwriter Ben Burgess the BMI country song of the year title by My Name,” but alcohol has not always been prominent. When Rhett, Underwood on Nov. 9, and the Country Airplay chart dated Nov. 24 reveals Randy Travis reenergized traditional country in the mid-1980s Make Xmas Special a format that remains whiskey bent, if not hellbound. Seven of while mostly avoiding adult beverages as a topic, the thirst for Page 11 the songs on that list liquor dwindled. The — including HAR- trend turned around DY’s “One Beer” so strongly that three (No. 5), Lady A’s hits in the late-1990s FGL’s Next Album Is “Champagne Night” — Collin Raye’s ‘Wrapped’ (No. 12) and Kelsea “Little Rock,” Dia- Page 11 Ballerini’s “Hole in mond Rio’s “You’re the Bottle” (No. 14) Gone” and Kenny — posit an alcohol Chesney’s “That’s Makin’ Tracks: reference boldly in Why I’m Here” — took ‘Hung Up’ On the title. -

NEW DEAL • Summer 2014

Carry It On Carry It On Local 1000 Local 1000 Chorus D=170 ChorusG G /B C D G G D=170 Voice G G /B C D G G Voice Pay it for ward car ry it on! car ry it for ward 'til the day is done Pay it for ward Voice Pay it for ward car ry it on! car ry it for ward 'til the day is done Pay it for ward Voice Pre-Chorus 6 G /B C D G D Pre-Chorus V. 6 G /B C D G D V. car ry it on! car ry it for ward 'til the day is done. Car ry it on V. car ry it on! car ry it for ward 'til the day is done. Car ry it on Oh my Sis V. 12 G D Oh my Sis V. 12 G D Why didn’tCar ry it on we thinkCar ry itof on this earlier?Car ry it on V. V. by Steve Eulberg Car ry it on Car ry it on Car ry it on ters Oh myForBro the thirdthers time, members gathered Ohandmy JohnPar McCutcheon.ents for V. hat is the question I kept asking for a few days at the historic Highlander We dreamed of our near and long- myself afterters we completedVerse the Oh 1Center,my Bro in Newthers Market, Tennessee. Ohtermmy Parfuture as anents interwoven webfor T17finalG portion of our MembersG They came from across the continent, of musical artists, supportingD G and Retreat at Highlander this past May.Verse 1this time to ponder how to “Carry It On.” challenging each other to Carry It On. -

Criffel Creek 07.06.2015 41 Songs, 1.7 Hours, 238.4 MB

Page 1 of 2 Criffel Creek 07.06.2015 41 songs, 1.7 hours, 238.4 MB Name Time Album Artist 1 Cripple Creek 1:32 Blue Grass Favorites The Scottsville Squirrel Barkers 2 I'll Meet You In Church Sunday Morning 2:47 The Father Of Bluegrass Bill Monroe 3 Here Comes A Broken Heart Again 2:59 Band Of Ruhks (M) Band Of Ruhks 4 Wide River To Cross 4:01 Papertown Balsam Range 5 Ashoken Farewell 3:09 Anything Goes Bonnie Phipps 6 Criffel ... (Pause) ... Son Into Your Sunday - DRY 0:05 Jingles Alive Radio 7 Already There 3:02 Anna Laube Anna Laube 8 Old Brown County Barn 2:44 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Michael Cleveland 9 You'd Better Get Right 1:50 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… The Vern Williams Band 10 Voice From On High 2:21 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Joe Val & The New England Bluegrass Boys 11 Lonesome Moonlight Waltz 3:52 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… The Bluegrass Album Band 12 Dog House Blues 3:17 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Nashville Bluegrass Band 13 Criffel ... Bluegrass & Americana - DRY 0:05 Jingles Alive Radio 14 Walls Of Time 3:49 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… The Johnson Mountain Boys 15 Big Mon 2:52 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Tony Rice 16 Footprints In The Snow 2:39 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… IIIrd Tyme Out 17 Jerusalem Ridge 4:39 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Michael Cleveland 18 Mansions For Me 3:38 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Bobby Osborne 19 In Despair 2:13 Bill Monroe Centennial Celebration: A Classic Blueg… Ralph Stanley & The Clinch Mountain Boys 20 Criffel .. -

B Uegrass Canada I

BUEGRASS CANADA I The official magazine of the Bluegrass Music Association of Canada www.bluegrasscanada.ca SELDOM SCENE 2012 1976 VOLUME 6 ISSUE 3 AUGUST 2012 WHAT"S INSIDE President Secretary Denis Chadbourn Leann Chadbourn Editor's Message-Pg 2 705-776-7754 705-776-7754 President's Message-Pg 3 Vice-president Treasurer Tips for Bands-Pg 4 Dave Porter Roland Aucoin The Western Perspective-Pg 6 905-635-1818 Feature Article-SELDOM SCENE-Pgs. 7-9 Q & A's With Steep Canyon Rangers-Pgs. 10-13 Maritime Notes Pg. 16 Providence Bay 2012 Pg-18 Directors at Large Advertising Rates Pg 19 Gord deVries Murray Hale 705-4 7 4-2217 Organizational Memberships -Pgs. 20 & 21 519-668-0418 Donald Tarte Tasha Heart-Social Media Just A Bluegrass Wife-Pgs. 23-26 877 -876-3369 Wilson Moore Congratulations to Spinney Brothers-Pg 26 Bill Blance Jerry Murphy, Region 1 SPECIAL NOTICE-Pg. 27 Representative 905-451-9077 Tim's CD Reviews-(Unavailable for this publication) Rick Ford- Region 4 Music Biz Article (Unavailable for this publication) Representative Advertising Pages-various pages Editor's Message - Any bands wishing to have this information included must provide itto me before September 15th, 2012. The Leann Chadbourn email address to send it to is at the bottom of this page We have some great articles in this issue with our trusty and on the Notice. writers, Gord DeVries, Denis Chadbourn, Diana van Holten, Wilson Moore & Darcy Whiteside. Since it's vacation time I Again, BMAC welcomes any interesting articles or infor took it seriously, and didn't get out reminders to everyone for mation relevant to Bluegrass and are hopeful to start receiv our deadline dates so we will be missing our Music Biz Arti ing articles from Coast to Coast. -

2020 Winter BMAM Newsletter

Bluegrass Music Association of Maine Winter 2020 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF BLUEGRASS BOOKS ABOUT BLUEGRASS MUSIC by Stan Keach I can think of three reasons why writing a short article covering books about bluegrass music might be a good idea for the winter newsletter: 1. There’s just not much current “news” about bluegrass music — not here in Maine, and not anywhere. Bands are mostly pretty inactive; there are no jams. 2. Some people have more time to read than usual, because there are no live concerts right now, no festivals, no jams. And, though I think a lot of bluegrass fans don’t realize this, there are many excellent books available about our fa- vorite subject. 3. If we can get this edition of The Bluegrass Express out early enough, it may spur a few Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs on the Grand Ole Opry, Dec. 8, 1945 people to buy a book or 2 for their favorite blue- grass music fans for a holiday gift. Seventy-five years ago, on December 8th, 1945, Bill Monroe and the So . here are seven of my favorite books Bluegrass Boys appeared on the Grand Ole Opry with a new line-up that related to bluegrass music. Most of these books, included 21-year-old Earl Scruggs playing a style of syncopated 3-finger though not brand new, are readily available from picking on the banjo that had never been heard before, and it absolutely booksellers of all kinds. And even if your local electrified the audience. Scruggs’ fiery banjo picking, Monroe’s frantic library doesn’t have one of these books, it can mandolin picking, and Chubby Wise’s bluesy fiddling, all done at a blis- likely get it through interlibrary loan; ask your tering pace; the bass thumping on the down beat, Monroe’s chop on the off librarian about that. -

“The Stories Behind the Songs”

“The Stories Behind The Songs” John Henderson The Stories Behind The Songs A compilation of “inside stories” behind classic country hits and the artists associated with them John Debbie & John By John Henderson (Arrangement by Debbie Henderson) A fascinating and entertaining look at the life and recording efforts of some of country music’s most talented singers and songwriters 1 Author’s Note My background in country music started before I even reached grade school. I was four years old when my uncle, Jack Henderson, the program director of 50,000 watt KCUL-AM in Fort Worth/Dallas, came to visit my family in 1959. He brought me around one hundred and fifty 45 RPM records from his station (duplicate copies that they no longer needed) and a small record player that played only 45s (not albums). I played those records day and night, completely wore them out. From that point, I wanted to be a disc jockey. But instead of going for the usual “comedic” approach most DJs took, I tried to be more informative by dropping in tidbits of a song’s background, something that always fascinated me. Originally with my “Classic Country Music Stories” site on Facebook (which is still going strong), and now with this book, I can tell the whole story, something that time restraints on radio wouldn’t allow. I began deejaying as a career at the age of sixteen in 1971, most notably at Nashville’s WENO-AM and WKDA- AM, Lakeland, Florida’s WPCV-FM (past winner of the “Radio Station of the Year” award from the Country Music Association), and Springfield, Missouri’s KTTS AM & FM and KWTO-AM, but with syndication and automation which overwhelmed radio some twenty-five years ago, my final DJ position ended in 1992. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center, our multimedia, folk-related archive). All recordings received are included in Publication Noted (which follows Off the Beaten Track). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention Off The Beaten Track. Sincere thanks to this issues panel of musical experts: Roger Dietz, Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Andy Nagy, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Elijah Wald, and Rob Weir. liant interpretation but only someone with not your typical backwoods folk musician, Jodys skill and knowledge could pull it off. as he studied at both Oberlin and the Cin- The CD continues in this fashion, go- cinnati College Conservatory of Music. He ing in and out of dream with versions of was smitten with the hammered dulcimer songs like Rhinordine, Lord Leitrim, in the early 70s and his virtuosity has in- and perhaps the most well known of all spired many players since his early days ballads, Barbary Ellen. performing with Grey Larsen. Those won- To use this recording as background derful June Appal recordings are treasured JODY STECHER music would be a mistake. I suggest you by many of us who were hearing the ham- Oh The Wind And Rain sit down in a quiet place, put on the head- mered dulcimer for the first time.