Martin Heidegger's Notion of the Work of Art As Welteröffnung

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ontological-Ontic Character of Mythology

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-25-2017 12:00 AM The Ontological-Ontic Character of Mythology Jeffrey M. Ray The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. John Verheide The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Jeffrey M. Ray 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, and the Metaphysics Commons Recommended Citation Ray, Jeffrey M., "The Ontological-Ontic Character of Mythology" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 4821. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/4821 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis submission interrogates the concept of mythology within the opposing philosophical frameworks of the world as either an abstract totality from which ‘truth’ is derived, or as a chaotic background to which the subject brings a synthetic unity. Chapter One compares the culturally dominant, classical philosophical picture of the world as a necessary, knowable totality, with the more recent conception of the ‘world’ as a series of ideational repetitions (sense) grafted on to material flows emanating from a chaotic background (non-sense). Drawing on Plato, Kant, and Heidegger, I situate mythology as a conception of the false—that which fails to correlate with the ‘world’ as a necessary whole. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Depopulation: on the Logic of Heidegger's Volk

Research research in phenomenology 47 (2017) 297–330 in Phenomenology brill.com/rp Depopulation: On the Logic of Heidegger’s Volk Nicolai Krejberg Knudsen Aarhus University [email protected] Abstract This article provides a detailed analysis of the function of the notion of Volk in Martin Heidegger’s philosophy. At first glance, this term is an appeal to the revolutionary mass- es of the National Socialist revolution in a way that demarcates a distinction between the rootedness of the German People (capital “P”) and the rootlessness of the modern rabble (or people). But this distinction is not a sufficient explanation of Heidegger’s position, because Heidegger simultaneously seems to hold that even the Germans are characterized by a lack of identity. What is required is a further appropriation of the proper. My suggestion is that this logic of the Volk is not only useful for understanding Heidegger’s thought during the war, but also an indication of what happened after he lost faith in the National Socialist movement and thus had to make the lack of the People the basis of his thought. Keywords Heidegger – Nazism – Schwarze Hefte – Black Notebooks – Volk – people Introduction In § 74 of Sein und Zeit, Heidegger introduces the notorious term “the People” [das Volk]. For Heidegger, this term functions as the intersection between phi- losophy and politics and, consequently, it preoccupies him throughout the turbulent years from the National Socialist revolution in 1933 to the end of WWII in 1945. The shift from individual Dasein to the Dasein of the German People has often been noted as the very point at which Heidegger’s fundamen- tal ontology intersects with his disastrous political views. -

Outline of a Sociological Theory of Art Perception∗

From: Pierre Bordieu The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature ©1984, Columbia University Press Part III: The Pure Gaze: Essays on Art, Chapter 8 Outline of a Sociological Theory of Art Perception∗ PIERRE BOURDIEU 1 Any art perception involves a conscious or unconscious deciphering operation. 1.1 An act of deciphering unrecognized as such, immediate and adequate ‘comprehension’, is possible and effective only in the special case in which the cultural code which makes the act of deciphering possible is immediately and completely mastered by the observer (in the form of cultivated ability or inclination) and merges with the cultural code which has rendered the work perceived possible. Erwin Panofsky observes that in Rogier van der Weyden’s painting The Three Magi we immediately perceive the representation of an apparition’ that of a child in whom we recognize ‘the Infant Jesus’. How do we know that this is an apparition? The halo of golden rays surrounding the child would not in itself be sufficient proof, because it is also found in representations of the nativity in which the Infant Jesus is ‘real’. We come to this conclusion because the child is hovering in mid-air without visible support, and we do so although the representation would scarcely have been different had the child been sitting on a pillow (as in the case of the model which Rogier van der Weyden probably used). But one can think of hundreds of pictures in which human beings, animals or inanimate objects appear to be hovering in mid-air, contrary to the law of gravity, yet without giving the impression of being apparitions. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

52 Philosophy in a Dark Time: Martin Heidegger and the Third Reich

52 Philosophy in a Dark Time: Martin Heidegger and the Third Reich TIMOTHY O’HAGAN Like Oscar Wilde I can resist everything except temptation. So when I re- ceived Anne Meylan’s tempting invitation to contribute to this Festschrift for Pascal Engel I accepted without hesitation, before I had time to think whether I had anything for the occasion. Finally I suggested to Anne the text of a pub- lic lecture which I delivered in 2008 and which I had shown to Pascal, who responded to it with his customary enthusiasm and barrage of papers of his own on similar topics. But when I re-read it, I realized that it had been written for the general public rather than the professional philosophers who would be likely to read this collection of essays. So what was I to do with it? I’ve decided to present it in two parts. In Part One I reproduce the original lecture, unchanged except for a few minor corrections. In Part Two I engage with a tiny fraction of the vast secondary literature which has built up over the years and which shows no sign of abating. 1. Part One: The 2008 Lecture Curtain-Raiser Let us start with two dates, 1927 and 1933. In 1927 Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (volume II) was published. So too was Martin Heidegger’s magnum opus Being and Time. In 1933 two appointments were made: Hitler as Chancellor of the German Reich and Heidegger as Rector of Freiburg University. In 1927 it was a case of sheer coincidence; in 1933 the two events were closely linked. -

Temporality and Historicality of Dasein at Martin Heidegger

Sincronía ISSN: 1562-384X [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara México Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Javorská, Andrea Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Sincronía, no. 69, 2016 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=513852378011 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Filosofía Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Andrea Javorská [email protected] Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Eslovaquia Abstract: Analysis of Heidegger's work around historicity as an ontological problem through the existential analytic of Being Dasein. It seeks to find the significant structure of temporality represented by the historicity of Dasein. Keywords: Heidegger, Existentialism, Dasein, Temporality. Resumen: Análisis de la obra de Heidegger en tornoa la historicidad como problema ontológico a través de la analítica existencial del Ser Dasein. Se pretende encontrar la estructura significativa de temporalidad representada por la historicidad del Dasein. Palabras clave: Heidegger, Existencialismo, Dasein, Temporalidad. Sincronía, no. 69, 2016 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Martin Heidegger and his fundamental ontology shows that the question Received: 03 August 2015 Revised: 28 August 2015 of history belongs among the most fundamental questions of human Accepted: -

MF-Romanticism .Pdf

Europe and America, 1800 to 1870 1 Napoleonic Europe 1800-1815 2 3 Goals • Discuss Romanticism as an artistic style. Name some of its frequently occurring subject matter as well as its stylistic qualities. • Compare and contrast Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine reasons for the broad range of subject matter, from portraits and landscape to mythology and history. • Discuss initial reaction by artists and the public to the new art medium known as photography 4 30.1 From Neoclassicism to Romanticism • Understand the philosophical and stylistic differences between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. • Examine the growing interest in the exotic, the erotic, the landscape, and fictional narrative as subject matter. • Understand the mixture of classical form and Romantic themes, and the debates about the nature of art in the 19th century. • Identify artists and architects of the period and their works. 5 Neoclassicism in Napoleonic France • Understand reasons why Neoclassicism remained the preferred style during the Napoleonic period • Recall Neoclassical artists of the Napoleonic period and how they served the Empire 6 Figure 30-2 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Coronation of Napoleon, 1805–1808. Oil on canvas, 20’ 4 1/2” x 32’ 1 3/4”. Louvre, Paris. 7 Figure 29-23 JACQUES-LOUIS DAVID, Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ 10” x 13’ 11”. Louvre, Paris. 8 Figure 30-3 PIERRE VIGNON, La Madeleine, Paris, France, 1807–1842. 9 Figure 30-4 ANTONIO CANOVA, Pauline Borghese as Venus, 1808. Marble, 6’ 7” long. Galleria Borghese, Rome. 10 Foreshadowing Romanticism • Notice how David’s students retained Neoclassical features in their paintings • Realize that some of David’s students began to include subject matter and stylistic features that foreshadowed Romanticism 11 Figure 30-5 ANTOINE-JEAN GROS, Napoleon at the Pesthouse at Jaffa, 1804. -

Martin Heidegger's Phenomenology and the Science of Mind

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Martin Heidegger's phenomenology and the science of mind Charles Dale Hollingsworth Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hollingsworth, Charles Dale, "Martin Heidegger's phenomenology and the science of mind" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2713. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2713 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARTIN HEIDEGGER’S PHENOMENOLOGY AND THE SCIENCE OF MIND A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of Philosophy by Charles Dale Hollingsworth B.A., Mississippi State University, 2003 May 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................................................iii Chapter 1 The Computational Model of Mind and its Critics..........1 2 One Attempt at a Heideggerean Approach to Cognitive Science...........................................................................14 3 Heidegger on Scientific -

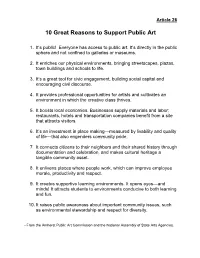

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

The Ontic Account of Scientific Explanation

Chapter 2 The Ontic Account of Scientific Explanation Carl F. Craver Abstract According to one large family of views, scientific explanations explain a phenomenon (such as an event or a regularity) by subsuming it under a general representation, model, prototype, or schema (see Bechtel, W., & Abrahamsen, A. (2005). Explanation: A mechanist alternative. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 36(2), 421–441; Churchland, P. M. (1989). A neurocomputational perspective: The nature of mind and the structure of science. Cambridge: MIT Press; Darden (2006); Hempel, C. G. (1965). Aspects of scientific explanation. In C. G. Hempel (Ed.), Aspects of scientific explanation (pp. 331– 496). New York: Free Press; Kitcher (1989); Machamer, P., Darden, L., & Craver, C. F. (2000). Thinking about mechanisms. Philosophy of Science, 67(1), 1–25). My concern is with the minimal suggestion that an adequate philosophical theory of scientific explanation can limit its attention to the format or structure with which theories are represented. The representational subsumption view is a plausible hypothesis about the psychology of understanding. It is also a plausible claim about how scientists present their knowledge to the world. However, one cannot address the central questions for a philosophical theory of scientific explanation without turning one’s attention from the structure of representations to the basic commitments about the worldly structures that plausibly count as explanatory. A philosophical theory of scientific explanation should achieve two goals. The first is explanatory demarcation. It should show how explanation relates with other scientific achievements, such as control, description, measurement, prediction, and taxonomy. The second is explanatory normativity. -

C. Aesthetics of Existence Nietzsche and Heidegger

C. AESTHETICS OF EXISTENCE NIETZSCHE AND HEIDEGGER CI) LIFE AND ETERNAL RECURRENCE NIETZSCHE Introduction Nietzsche revalues the question of freedom in response to what he considers the repressive, life-denying moral laws underwritten by an over-bearing conceptual ratio since the time of Socrates and Plato. What has become the culturally instilled dualism of body and mind, an exclusion of somatic drives from any determining influence in the process of so-called rational thought, Nietzsche argues, continues to distort the modern questions of freedom and moral truth. Critical of the transcendental a priori character of Kant's categorical imperative and the dialectical rationality governing Hegel's secular metaphysics of Spirit, Nietzsche severs any necessary link between freedom and the conceptual ratio. Freedom now finds expression in the existential poiesis of an inner, self-reflexive pathos of aesthetic sensibility. This means that freedom is no longer tied to normative social relations with others nor to a metaphysical telos altogether beyond reach, but rather to values which best suit an individual's particular existential goals. No longer governed by any conceptually determinate, legislative moral judgement, these goals and the values supporting them are determined through a process of aesthetic evaluation. The actions resulting from this self-reflexive, aesthetic evaluation resemble those of an artist when producing a work of art. Indeed Nietzsche considers the actualisation of freedom to be indistinguishable from the actualisation of life as a work of art. Nietzsche thereby revalues the will to freedom as a self-styled evaluative aesthetics. What sustains this specifically aesthetic revaluation of freedom, Nietzsche indicates_ is a faith in the fateful principle of eternal recurrence.