Student Activism at Eastern Michigan University 1961-1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMU Campus Map.Pdf

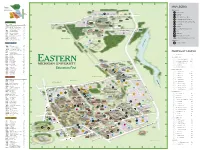

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Campus West MAP LEGEND Subdivisions L H and Color Code PARKING ICONS FACULTY/STAFF North Main Campus rs Mid RESERVED South NORTH HEWITT ROAD FAMILY HOUSING RESIDENT SICC COMMUTER/FACULTY/STAFF/GA OEST K RYNS K COMMUTER/FAC./STAFF/GA/RES. HALL WEST CAMPUS cv CONV OLDS COMMUTER _________________ABBR. NAME GRID IPF CONV Convocation Center K5 TEAM RESIDENT COOP Darrell H. Cooper Building J9 GUEST/PAID PARKING $1/HOUR IPF Indoor Practice Facility K8 COOP OEST Oestrike Stadium K8 UNIV w WEST w WESTVIEW STREET OLDS Olds/Marshall Track K7 w FREE RYNS Rynearson Stadium K6 J ws J HANDICAP SBC Softball Complex I6 SICC Paul Siccluna Soccer Field K8 w PARKING METER $1/HOUR TEAM Team Building K7 UNIV University House J3 WEST CAMPUS MOTORCYCLE GRIDS B5, E3, E4, C6, D8 WEST Westview Apartments J6 sc SBC OTHER ICONS NORTH CAMPUS EMERGENCY PHONE NORTH HURON RIVER DRIVE _________________ABBR. NAME GRID I I CENR Central Receiving G8 HURON RIVER CORN Cornell Court Apartments G7 CROSS Crossroads Market Place F8 DPS Department of Public Safety F8 A PARKING BY CAMPUS EEAT Eastern Eateries D8 INSLEY ST. (First Year Center) FLET Fletch er School/Autism Ctr. H6 __________________ TYPE CODE AND LOT NAME GRID HILL Hill Hall F8 HOYT Hoyt Hall G8 H H WEST CAMPUS LOTS LAKE Lakehouse E8 cv Convocation Center Lot K5 PHLP Phelps Hall D8 FLET PHYS Physical Plant D10 rs Rynearson Stadium Lot L6–L8 PITT Pittman Hall F8 CORNELL ROAD sc Softball Complex Lot I5 PUTN Putnam Hall C9 cc EASTBROOKcc VARS w Westview J5–J6 SCUL Sculpture Studio G8 CORN ws Westview Street Lot J8 SELL Sellers Hall D8 CENR MAYHEWcc STUD Student Center E7 cc NORTH CAMPUS LOTS UPRK University Park E7 G c SCUL G L VARS Varsity Field G8 Y b VILL MAN ST. -

Suspect in Country Meadows Apartment Complex Faces Charges

PG. X2 PG. X3 PG. X7 REFERSENATE HEAD MATCHES HERE REFERAN UPHILL HEAD BATTLE HERE AND REFEREMU FOOTBALL HEAD HERE AND ANDDONATIONS HERE AND FOR HEREFOR HEALTHCARE AND HERE AND HEREBECOMES AND HEREBOWL AND HERESTUDENT AND EMERGENCY HERE HERE AND HERE JJJJJ HEREELEGIBLE AND HERE JJJJJ ANDFUND HERE JJJJJ MONDAY,MONDAY, DECEMBER NOVEMBER 2 18 | VOLUME | VOLUME 136, 136, ISSUE ISSUE 12 11 SERVING EMU AND YPSILANTI SINCE 1881 Office of Wellness and Community Responsibility provides students with access to affordable health insurance MEGAN GIRBACH to determine if an individual is eligible to "We unfortunately live in dangerous STUDENT ORG. REPORTER receive free health insurance [Medicaid] times," Thomas said. "It's good to have or help reduce the cost of insurance coverage." An unexpected trip to the emergency [Marketplace insurance subsidies]." Thomas hopes that after the event, room can lead to expensive bills when "The overall goal is that all EMU students realize just how important health one doesn't have health insurance. To students have health insurance," Pomante insurance really is. help students avoid situations like these, added. "This event is one way we're "You can rack up a lot of medical the Office of Wellness and Community working toward that goal." bills," Thomas explained. "Young people Responsibility (OWCR) hosted an Many college students may not don't need damage to their credit. They affordable health insurance event on Nov. consider looking into health insurance. need to focus on their mental, physical 20 in room 250 of the Student Center. "Having health insurance coverage is and spiritual health." Certified enrollment agents from one of the most important things a student Brice Marich, a student looking to the Washtenaw Health Initiative (WHI) can do for their health and success in enroll at EMU, came to the event to learn spoke with students to help them look college," Pomante explained. -

EMU Today, November 26, 2013 Eastern Michigan University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Eastern Michigan University: Digital Commons@EMU Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU EMU Today EMU Today Fall 11-26-2013 EMU Today, November 26, 2013 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/emu_today Recommended Citation "EMU Today, November 26, 2013." Eastern Michigan University Division of Communications. EMU Archives, Digital Commons @ EMU (http://commons.emich.edu/emu_today/286). This University Communication is brought to you for free and open access by the EMU Today at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in EMU Today by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuesday, November 26, 2013 SPECIAL NOTICES: BOARD OF REGENTS MEETING: The EMU Board of Regents will hold its December board meeting on Tuesday, Dec. 10 , at 1:30 p.m., in room 201, Welch Hall. Below is the schedule for the committee meetings. All meetings are in Welch Hall. • Faculty Affairs: 8:00 - 8:45 a.m., Room 205 • Athletic Affairs: 9:00 - 9:45 a.m., Room 201 • Educational Policies: 9:00 - 9:45 a.m., Room 205 • Student Affairs: 10:00 - 10:45 a.m., Room 205 • Finance, Audit and Investment: 11:30 - 12:15 p.m., Room 201 For additional information, please visit the Board of Regents homepage or contact Vicki Reaume at 487-2410 or email [email protected] . EXHIBITION TAKES A LOOK AT THE EVOLUTION OF TRACK & FIELD AT EMU: The University Archives has an exhibit on the third floor in Halle Library (ourside Archives). -

Focus EMU, March 17, 2009

1 \ � ,·· im;·�· 1:. 1r,,;-;.1n1 ,-. r,.._,,... ll \''i\.� 1 '�;.· fJ.-.i'!J:' r;iT"'..V ·.�f:.,,v, ,'.:.,1r::"-: ·'>I � r; • ',:..:,.:/·,\ � l!J, , 1,-, w:;), I I EMU HOME Featured EMU celebrates 160 years this month; longtime employees reflect on Articles campus changes through the years Editor's Note: Eastern Michigan University celebrates its 160th anniversary this month. FOCUS EMU talked to some longtime EMU employees about their reflections and the changes they've seen on campus from the 1960s to the present. :::EMU celebrates 160 years this month; Today, Sally McCracken reflects and sees Eastern Michigan University as a choice school longtime employees for high school students in southeastern Michigan, especially the Detroit suburban area. reflect on campus changes through the But when the commication, media and years theater arts professor first came to EMU :::iNew EMU Ph.D. helps 40 years ago, she saw dollar signs. She OLLEGE of educators understand initially came to EMU because the impact of environment university offered $300 more than The on learning University of Southern California-Long :::EMU to celebrate Salute Beach. to Excellence Week "Isn't that awful," she laughs. "I was March 23-27 mercenary." :::Wunder discusses benefits of Healing In recognition of the university's 160th Foods Pyramid during anniversary, some longtime faculty and National Nutrition Month staff shared their reflections on their ::Presidential Scholars EMU experience, how the university has pursue passions, explore changed, and even how it hasn't. options :::Obits: Former EMU "We're regional, and that's never football great, special changed. What has changed is we're I 8 4 9 2 0 0 9 projects crewperson die comprehensive now," McCracken said. -

Focus EMU, February 6, 2007

EASTERN MICHIGAN UN fVERSITY EMU HOME Feb. 6, 2007 Volume 54, No. 21 FOCU Featured Bowen Field House indoor track facility repaired; op.en for use Articles At approximately 1 :30 p.m. Jan. 27, a group of mile runners fro11 Eastern Michigan University, Central Michigan and the University of Detroit Mercy circled the 200-meter oval in Bowen Field House, marking the inaugural lap of the ne� Tartan surface track. ::.2Bowen Field House It was a far cry from the scene last September when the track and surrounding surface indoor track facility in Bowen resembled a giant waterbed after an underground pipe burst and flooded the repaired; open for use facility. So much water rose, the track surface actually was floating in some spots while =iEMU reviews court outside areas in the corners near the long jump pit and mechan cal room actually ruling prohibiting same dropped two feet during the Sept. 8 incident, said Dan Salk, EMJ's assistant director, sex partner benefits risk management and worker's compensation. =iEMU student to serve on BBC Oscar panel "Certain areas of the floor ElFriends of the Library were heaving," Salk complete inaugural year recalled. "Larry Ward :2Presidential Scholars (director of facility planned to attend EMU; maintenance) described it scholarship is just icing as the largest waterbed on the cake you've ever seen." :JEMU's College of Business signs agreement with As a result, the facility was university in Macao, closed for repairs and a few China EMU athletic events ciPhoto: Lecturer Frank scheduled in early January Fedel and skeleton were either moved to other brave cold temperatures venues or canceled. -

Emergency Operations Center (EOC) Plan Procedures

Emergency Operations Center Procedure Rev. 1.02 May 2010 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK CONTENTS Record of Revisions ..................................................................................................... iii Distribution List ............................................................................................................ iv I. Purpose ........................................................................................................... 1 II. Situation and Assumptions ............................................................................ 1 A. Situation .......................................................................................................... 1 B. Assumptions ................................................................................................... 2 III. Concept of Operations .................................................................................... 2 A. EOC Location .................................................................................................. 2 B. Types of Emergencies .................................................................................... 2 C. Emergency Classification Levels ................................................................... 3 IV. Organization & Assignment of Responsibilities ........................................... 4 A. University President ....................................................................................... 4 1. Declaration of a Campus State of Emergency ............................................. -

Focus EMU, January 27, 1998

... - . REGENTS. ISSUE_ . FOCUS EMU News for Volume 45 Eastern Michigan University Number23 Jan.27, 1998 Faculty and Staff Education secretary Riley slated as commencement speaker U.S. Secretary of Education Richard W. Riley will be the commencement speaker at Eastern Michigan lncarnati re-elected chairman of EMU Board of Regents University this spring, following action at the Jan. 20 Philip A. lncarnati, president and chief execu Dr. Gayle Thomas, a dentist from Dearborn,was Board of Regents meeting. tive officer of McLaren Health Care Corp. of Flint, re-elected vice chair. She has been a regent since Riley, who has served as a member of President was re-elected chairman of the Eastern Michigan 1991 and served as vice chair of the board in 1992 Clinton's Cabinet since 1992, will present the morning University Board of Regents at its regular meeting and 1997. She has had a general dentistry practice in commencement address Sunday, April 26, when East Jan. 20. Dearborn since 1983 and was a part-time assistant ern will host graduation exercises in Bowen Field lncarnati, a resident of Fenton, has been an professor at the University of DetroitMercy School House. U.S. Representative Lynn N. Rivers of Ann Arbor EMU regent since 1992 and chair of the Board of of Dentistry for 14 years. will present the commencement address during after Regents since 1995. He earned a business admin Re-elected as secretary to the board was Dana noon ceremonies. Both Riley and Rivers will receive istration degree in 1976 and a master's degree in Aymond, and re-elected treasurer was Patrick J. -

The Edge, Fall 2005

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 2005 The dE ge, Fall 2005 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "The dE ge, Fall 2005" (2005). Alumni News. 195. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/195 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cllris Hoiles (left) and Carl Thomas ('00) bring pro insights to EMU athletes. L___ _______________________ -- Who we are Welcoming a chance to serve My goal: Strengthening EMU through the support of its alumni I first visited EMU as a high school junior from Novi in 1988 , with my best friend. After a campus cour, we both enrolled that day. That visit began my 17-year e relationship with EMU, from a prospective student co VolumeThe3, Issue Eda 1 b Fall 2005 Alumni Association president. I graduated in 1993 with a journalism degree and ADVANCEMENT STAFF Vice president of advancement during my time on campus, I was edicor of the Aurora (interim) yearbook, a writer for the Eastern Echo and served as Thomas R. Stevick Executive director of execurive vice president of my sorority, Sigma Kappa. alumni relations My EMU experience has provided me excellent Vicki Reaume ('91, '96) Director of alumni programs opportunities, lifelong friends and memories of college Amy (Schulz) Spooner life chat I wouldn't trade with anyone. -

Focus EMU, November 6, 1990

Produced�$ Volume 37, Number 15 Public Information Nov. 6, 1990 ]1�0CUS EMU and Publications Rebuilt Sherzer Hall back in fine form Only 19 months after 11 was near the start of tl:e 1990 fall semester. ly destroyed by fire, Sherzer Hall is The construction of the original back in fine form and was officially Sherzer Hall was funded by a rededicated Oct. 27 in ceremonies $55,000 appropriation from the attended by EMU President Michigan Legislature and was built William E. Shelton as part of on land donaced by the people of Homecoming/P'arents Day 1990. Ypsilanti. When it opened it was The historic 1903 structure was known as the Normal College nearly destroyed by fire March 9, Science Builc.ing and it wasn't until 1989, less than one month after the 1958, after the building underwent EMU Board of Regents approved a significant renovations, that it was program statement to submit to the renamed Sherzer Hall in honor of state for funding its renovation and Dr. William H. Sherzer, who serv restoration. Although considered ed as geology professor and head for demolition, a decision was of the NaturaJ Science Department made in April of that year to re at EMU from 1892 until his death build Sherzer to its original glory. in 1932. After the fire, approximately 50 Except for an astronomy class percent of the building remained in room and the observatory on the tact and more than 70 percent of fourth floor, the building is used the original exterior masonry shell exclusively for art instruction and remained, including the unique hosts offices for some art faculty members on the fourth floor. -

Eastern Today, Volume VIII, Number 3, 1991 Eastern Michigan University

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 1991 Eastern Today, Volume VIII, Number 3, 1991 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "Eastern Today, Volume VIII, Number 3, 1991" (1991). Alumni News. 159. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/159 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume VIII, number 3 Eastern Today is published quarterly for members of the Alumni Associationof Easrern Michigan University and produced by the Officeof Public Information and University Publications. Pleasedirect questionsor comments to the Officefor Alumni Relations. Eastern Michigan University, c 0 N T E N T s Ypsilanti, Michigan 48197; (313) 487-0250. EASTERN TODAY Viewpoints ....................................................................... 2 EDITORlAL COMMIIT£E Preparing the University for the 21st Century .................. 4 George G. Beaudette, direcror of alumni relations Carole Lick, assistant director of alumni relations You Ase What You Eat ................................................... 10 BeverlyFarl ey, assistant direccor of university development Alumni Work co Promote Fimess ................................... 12 Eugene Smith, director of athletics Jim Streeter, spores information director No Rocking Chair for This Alumnus ............................. 14 Kathleen Tinney, assistant vice president, e.xecutive division Sue McKenzie, associate director of university publications D E R T M E N T Karen M. Pirron, editor p A s Nancy J. Mida, staff writer and alumni association representative Campus Commentary ...................................................... 1 S. Jhoanna Robledo. srudent writer Campus News ................................................................ -

Eastern Today, Summer 1989 Eastern Michigan University

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 1989 Eastern Today, Summer 1989 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "Eastern Today, Summer 1989" (1989). Alumni News. 33. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. resenting r. William E. Shelton, MU's new president e 1988 Honor Roll :umnus Tim McBride the White House &stern 1/Jday is published four times a �ar for alumni and friends of &stern Michigan Uniwrsity and produced by rht Office of Public lnfonnarion and CONTENTS Uniwrsiry Publications. Please dirt!ct questions or comments ro rhe Officefor Alumni &larions, E:asrtrn Michigan Uniwrsity, lpsilanri, Michigan 48197; (313) 487-<J250. EASTERN TOIMY EDITORIAL COMMllTEE Jack Slater, dirt!c/Or of alumni rt!lations and uniwrsiry dew,lopmtnt Par Moron, associate dirtctor of alumni rt!larions Carole lick, assistant dirt!cror of alumni rtlarions Eugene Smirh, dirtctor of arhltrics Karhlun Tinney, tlirt!clor of uniwrsiry communications Sue McKLnve, associatedirt!ctor of uniwrsity pub/icarions Diane KLl/u, alumni associarion rt!prt!senrariw NancyJ. Mida, alumni association rt!prtsenrariw Jody Lynn &illy, srudent wriru Page 4 Page 7 Page 13 liz Cobbs, ediror GRAPmC ARTlS1S Lott/It Otis ThomJJ.r David Kiefi A heritage of teaching attracted Dr. William E. Shelton to EMU . -

Resource Design Group Ann Arbor, Michigan Princip

CITY -WIDE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY Ypsilanti, Michigan prepared by: Resource Design Group Ann Arbor, Michigan .. principals: Richard Macias ASLA Malcolm L. Collins AIA Richard A. Neumann AIA Robert A. Schweitzer Archeological Consultant: W. R. Stinson Black History Consultant: A. P. Marshall July 12, 1983 This project has been funded, in part, through a grant from the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service (under provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act) through the Michigan Department of State. TABLE OF CONTENTS I I. Introduction . • • • • • • 1 II. Statements of Significance • • 6 I A. Architecture 6 B. History ••• 30 I C. Archaeology • . 55 III. Review of Previous Surveys 61 I IV. Survey Methodology • . 61 v. Analysis of Problems • • 63 I VI. List of Sites 65 1 VII. Nominated Resources . '. • 67 VIII. Bibliography ••.• • 89 1 I I I I I. Introduction The following written, graphic and photographic material represents a survey of historically and architecturally significant properties in the 1 City of Ypsilanti, Michigan. The study area for this project consisted of the present (1982-83) incorporated area of the City of Ypsilanti. I While historical and architectural resources are described in some I detail and on the basis of extensive research and field work, archaeological resources are described only briefly in an overview statement of past i activity. No attempt was made to identify, document or nominate archae- ological resources as part of the study. 1 1 The survey of Ypsilanti and the resulting National Register of Historic Places Multiple Resource Nomination meet several requirements; but the 1 primary reason for carrying out this project was to utilize all of the ., tools that historic preservation offers for city development.