City Wide Historical and Architectural Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washtenaw County Historic District Commission

WASHTENAW COUNTY HISTORIC DISTRICT COMMISSION MEETING AGENDA DATE: Thursday, January 4, 2017 TIME: 5:30 pm – 7:00pm PLACE: Eastern County Government Center Office of Community & Economic Development – 2nd Floor 415 W. Michigan Avenue, Ypsilanti, MI Call to Order/Roll Call – Consent Agenda Approval of: • Minutes of November 2, 2017 • Agenda • Staff Report Public Comment Business: • Introductions and swearing in of Commissioners Snyder, Remensnyder, Ralph, and Cook by Edwin Peart, Washtenaw County Deputy Clerk • Commissioner Elections • Staffing Update • Local Historic Districts Updates o Existing Districts o Potential Designations . Thornoaks (Ann Arbor Township) • Current/Pending COAs o None at this time • Affidavit on Historic District Deeds o Update on Instrument . Adler signature notarized-12-5-17 . 8 of the 14 districts have affidavits filed with the County Clerk • Programming o Update on Current Legislation o Ongoing Heritage Tourism partnership with Convention & Visitors Bureau . Black Ypsi Storymap- Intern Tiffany worked with the Ypsilanti signage project to develop a story map from the content developed with a 2017 Michigan Humanities Council Grant. The signs are scheduled to be places in Spring 2018 http://washtenaw.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Shortlist/index.html?appid=43e7143e1fe7482aa82875 7fa2981bbd • Other Updates from Commissioners & Staff – All Adjournment Next Meeting: Thursday, March 1, 2017 Washtenaw County Eastern County Government Center Second Floor -- Above the 14A2 District Court, next to the Police Station 415 West Michigan -

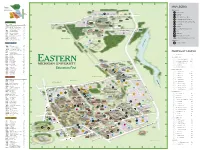

EMU Campus Map.Pdf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Campus West MAP LEGEND Subdivisions L H and Color Code PARKING ICONS FACULTY/STAFF North Main Campus rs Mid RESERVED South NORTH HEWITT ROAD FAMILY HOUSING RESIDENT SICC COMMUTER/FACULTY/STAFF/GA OEST K RYNS K COMMUTER/FAC./STAFF/GA/RES. HALL WEST CAMPUS cv CONV OLDS COMMUTER _________________ABBR. NAME GRID IPF CONV Convocation Center K5 TEAM RESIDENT COOP Darrell H. Cooper Building J9 GUEST/PAID PARKING $1/HOUR IPF Indoor Practice Facility K8 COOP OEST Oestrike Stadium K8 UNIV w WEST w WESTVIEW STREET OLDS Olds/Marshall Track K7 w FREE RYNS Rynearson Stadium K6 J ws J HANDICAP SBC Softball Complex I6 SICC Paul Siccluna Soccer Field K8 w PARKING METER $1/HOUR TEAM Team Building K7 UNIV University House J3 WEST CAMPUS MOTORCYCLE GRIDS B5, E3, E4, C6, D8 WEST Westview Apartments J6 sc SBC OTHER ICONS NORTH CAMPUS EMERGENCY PHONE NORTH HURON RIVER DRIVE _________________ABBR. NAME GRID I I CENR Central Receiving G8 HURON RIVER CORN Cornell Court Apartments G7 CROSS Crossroads Market Place F8 DPS Department of Public Safety F8 A PARKING BY CAMPUS EEAT Eastern Eateries D8 INSLEY ST. (First Year Center) FLET Fletch er School/Autism Ctr. H6 __________________ TYPE CODE AND LOT NAME GRID HILL Hill Hall F8 HOYT Hoyt Hall G8 H H WEST CAMPUS LOTS LAKE Lakehouse E8 cv Convocation Center Lot K5 PHLP Phelps Hall D8 FLET PHYS Physical Plant D10 rs Rynearson Stadium Lot L6–L8 PITT Pittman Hall F8 CORNELL ROAD sc Softball Complex Lot I5 PUTN Putnam Hall C9 cc EASTBROOKcc VARS w Westview J5–J6 SCUL Sculpture Studio G8 CORN ws Westview Street Lot J8 SELL Sellers Hall D8 CENR MAYHEWcc STUD Student Center E7 cc NORTH CAMPUS LOTS UPRK University Park E7 G c SCUL G L VARS Varsity Field G8 Y b VILL MAN ST. -

Coming Soon MAY 2016 BOARDING LOCATIONS Blake Transit Center 328 S Fifth Ave, Ann Arbor

Coming Soon MAY 2016 BOARDING LOCATIONS Blake Transit Center 328 S Fifth Ave, Ann Arbor Key Boarding locations 1 Liberty St 21 F F ou 33 i f th r th 3 FEDERAL A A BUILDING v v 30 29 31 PARKING STRUCTURE FOU 32 R 28 TH & 24 6 25 26 27 WILLIAM 5 BLAKE TRANSIT CENTER 4 22 AirRide 23 STOP William St Ypsilanti Transit Center 220 Pearl St, Ypsilanti Key Boarding 1 locations YPSILANTI TRANSIT CENTER 45 42 6 3 ST WASHINGTON ADAMS ST ADAMS 46 44 43 5 4 47 PEARL ST EMU COLLEGE 41 OF BUSINESS MICHIGAN AV TheRide operates two transit centers. In Ann Arbor most routes originate at the Blake Transit Center and in Ypsilanti most routes originate at the Ypsilanti Transit Center. Most buses at both transit centers leave at :03, :18, :33, or :48 minutes past the hour to coordinate transfers. *Boarding locations at both transit centers are subject to change. Version 1 12/22/15 COMMON DESTINATIONS GET READY! MEDICAL SOCIAL SERVICES Use this guide to help prepare Bortz Health Care 44 American Red Cross 5A/5D Glacier Hills Life-Care 65,66(Sat) Catholic Social Services 5A/5D for May 2016 service improvements. Maple Medical Center 31,32A,60 Center for Independent Living 6 St. Joseph-Mercy Hospital 3,24 Community Action Network 24 U-M Hospital 3,4A,23,32B,60,63,64 County Human Services 5A/5B/5C,6 VA Medical Center 3,66 County Towner Center 44 Routes NEW ROUTES Peace Neighborhood Ctr 32A,60 through Starting May 1, 2016 PARK & RIDE LOTS Women’s Center of Southeast MI 28,30,32A Green Road 65,66,23(evenings) Washtenaw United Way 24 April 30, 2016 your new route(s) -

100 Years of High School Basketball Tournaments – 1916-2016

Official publication of the Ypsilanti Historical Society, featuring articles and reminiscences of the people and places in the Ypsilanti area SPRING 2016 In This Issue... 100 Years of High School Basketball Tournaments – 1916-2016 ................1 By Eric Pedersen Council approves Eagle Statue ........6 Newspaper Reports Providing for the Family During the Great Depression: An Interview with Virginia Davis-Brown .......................8 By Eric Selzer A Travel Through Time: Riverside Park .................................12 By Jan Anschuetz April Movie Nights .........................17 By James Mann Michigan State Normal College Gymnasium. 100 YEARS George Ridenour - An Appreciation .............................18 of Michigan High School By Peg Porter Basketball Tournaments – 1916-2016 Summer and Winter Fun at Riverside Park .................................................20 BY ERIK PEDERSEN By Robert & Eric Anschuetz Sweet Memories .............................24 he Michigan State Normal School By Rodney Belcher Gymnasium in Ypsilanti was the Wilber Bowen was site of the first basketball game the person respon- Senator Alma Wheeler Smith ........26 T sible for bringing By Jacqueline Goodman to be held west of the Allegheny Moun- basketball teams to tains. Wilber Bowen, head of the newly Ypsilanti to help cele- Johnson Smith Catalogs .................28 brate the dedication established Physical Education major of the new Michigan By Gerry Pety program at the Normal School, was the State Normal School The Map Hoax ................................30 gymnasium. person responsible for bringing James By Jacqueline Goodman Naismith and his Springfield College Ypsilanti’s Forgotten Hero .............32 student basketball team to Ypsilanti By Jacqueline Goodman to help celebrate the dedication of the Basketball will celebrate a very spe- new Michigan State Normal School cial anniversary on March 23 -25, 2016. -

EMU Alumni Magazine, December 1967 Eastern Michigan University

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 1967 EMU Alumni Magazine, December 1967 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "EMU Alumni Magazine, December 1967" (1967). Alumni News. 80. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALUMNI MAGAZINE Volume XX • Number 2 • December, 1967 "A noble tradition of excellence has been estab lished •.Now we have the responsibility not only to cor.tinue that legacy but also to enlarge and enrich it."-President Harold E. Sponberg Eastern's Freshman Class Excels "This year's freshman class is the finest in Eastern Michigan University's history," according to the Dean of Admissions and Financial Aids, Ralph F. Gilden. "The class is about the same size as last year's freshman class-approximately 3,000 students. Of these students, about 97 per cent live in Michigan." "Each year since 1957, approximately 90 per cent of the members of freshman classes have ranked in the top one-half of their high school classes, and 75 per cent were in the top quarter of their classes," Dean Gilden added. Almost 15,000 students are enrolled at the University this fall. Of this number, 11,700 are undergraduates and 3,300 are graduate students. The Office of Admissions received 7,208 new applications for admission for the fall semester. -

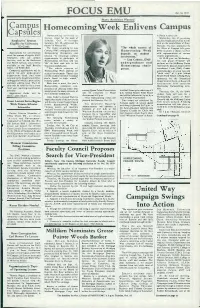

Focus EMU, October 16, 1979

FOCUS EMU Oct. 16, 1979 Many Activities Planned Campus Homecomin Week Enlivens Campus C 1 g a sues Homecoming activities at in Pease Auditorium. Eastern, slated for the week of Wednesday, Oct. 17, an all-day Employees' Spouses Sunday, Oct. 14 through Student Organizations Fair will be ... Eligible for University Saturday, Oct. 20, will feature the held on the second floor of Pray- theme "A Natural Hi!" ID Cards Harrold. The fair, sponsored by The theme, according to Lisa "The whole succes s of the Office of Campus Life, gives Coberly,EMU undergraduate and Homecoming Week EMU students a chance to meet Applications for identification Homecoming chairperson, was depend s on student with representatives of various cards for spouses of regular EMU selected "to encourage campus in volvement." student organizations. employees who use campus organizations to participate in At 12:30 p.m. on Wednesday, ,. facilities, such as the Bookstore Homecoming activities and say - Lisa Coberly, EMU the rock group "Frosted" will and Health Service, are currently 'Hi!' in their own way to the undergrad U ate and perform on the McKenny Union available in the Staff Benefits University community. Homecoming ch air- mall and the Queen's Court will be Office, 112 Welch Hall. "The whole success of per son. introduced. Later, EMU Greeks Completed applications will be Homecoming Week depends on will participate in a keg toss and signed by the appropriate student involvement. There's just "chick relay" at 4 p.m. behind department head and then not the student initiative in college Bowen Field House. A Bong Show returned to the Registration Office that's found in high school," sponsored by the Intramural in Briggs Hall where a photo of the Coberly added. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Submission Listings Michigan

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY SUBMISSION LISTINGS MICHIGAN FINDING AID Old Fire House No. 4, Kalamazoo Multiple Resource Area, Photo by Gary Cialdella, Kalamazoo Historical Society Prepared by National Park Service - Intermountain Region Museum Services Program Tucson, Arizona February 2015 National Register of Historic Places – Multiple Property Submission Listings - Michigan 2 National Register of Historic Places – Multiple Property Submission Listings - Michigan Scope and Content Note: The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. - From the National Register of Historic Places site: http://www.nps.gov/nr/about.htm The Multiple Property Submission (MPS) listings records are unique in that they capture historic properties that are related by theme, general geographic area, and/or period of time. The MPS is the current terminology for submissions of this kind; past iterations include Thematic Resource (TR) and Multiple Resource Area (MRA). Historic properties nominated under the MPS rubric will contain individualized nomination forms and will be linked by a Cover Sheet for the overall group. Historic properties nominated under the TR and MRA rubric are nominated as part of the whole group and will contain portions of nominations that come directly from the group Cover Sheet. -

The Eastern Edge, Fall 1999" (1999)

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 1999 The aE stern Edge, Fall 1999 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "The Eastern Edge, Fall 1999" (1999). Alumni News. 226. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/226 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Eastern EASTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY·Office for Alumni Relations• Volume 3, Number 1 Fall Issue 1999 Alumni and friends "Come Back To The Future" and celebrate 150 years of learning at Eastern Michigan University. In this issue you will find a tentative schedule of Sesquicentennial Homecoming events taking place October 4 through 10. Homecoming Week will include Family Day, the EMU vs WMU football game and ending the week'sactivities will be the student concert at Pease Auditorium featuring "The Roots" Sunday, October 10. Mark your calendars now and come back to celebrate Eastern Michigan University's past and take a look at its future. Getting their hands andfeet Thefootball team is dirty, Eastern readyfor action and Michigan will take on the University Western Michigan students started UniversityBroncos, a new tradition Saturday, October 9. on campus last year with an ' OozeballMud Volleyball Tournament. ceived a mar riage proposal from Home coming King Matt Long The EMU Cheer Team will be on hand to share their during half "Go Green" spiritfor an Eagle's victory over Western time ofthe Michigan. -

Eastern, Winter 1982 Eastern Michigan University

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 1982 Eastern, Winter 1982 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "Eastern, Winter 1982" (1982). Alumni News. 240. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/240 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !- 1- Office for Alumni Relations BULK RATE 1: Eastern Michigan University Non-Profit Organization i Ypsilanti, Michigan 48197 ,-•"i U.S. POSTAGE ,. , PAID ,-,: Ypsilanti, Michigan . Permit No. 139 •i. Volume 5, Number 2, Winter, 1982 :· A Publication for Alumni and Friends of Eastern Michigan University FEBRUARY 2-7 EMU Players present "The Night of the Iguana" 7 p.m. Sunday Quirk Theater 4 Orchestra Concert 8 p.m. Pease Auditorium 7 Symphonic Band Concert 8 p.m. Pease Auditorium 7 Symphonic Band Concert 8 p.m. Pease Auditorium 14 Jazz Ensemble Concert 8 p.m. Pease Auditorium 21 University Choir Concert 8 p.m. Pease Auditorium MARCH 7 Michigan Opera Theater Pease Auditorium 14 Alumni Concert Band 4 p.m. Pease Auditorium 16 Faculty Recital Series IV 8 p.m. New Alexander Recital Hall 18-20 National Conference on Spanish for Bilingual Careers in Business Hoyt Conference Center 21 Concert Winds 8 p.m. Pease Auditorium 26-28 EMU Players present "Kiss Me Kate" 8 p.m., 7 p.m. Sunday Quirk Theater 29 Alvin Ailey Dance Company 8 p.m. -

“Lost Restaurants” of Ypsilanti

Official publication of the Ypsilanti Historical Society, featuring historical articles and reminisces FALL 2010 of the people and places in the Ypsilanti area. In This Issue... “Lost Restaurants” of Ypsilanti “Lost Restaurants” of Ypsilanti _____1 Readers share their memories of restaurants that By Peg Porter were once part of the town’s business & social life. Dining in the Museum ___________6 Introduction: The summer issue of Gleanings stools and a kitchen behind. Popular with The YHS Museum was recently the site of a included a call to our readers to share their the downtown lunch time crowd, the menu gala dinner cooked by John Kirkendall. memories of restaurants that had once been consisted primarily of hamburgers, hot dogs, Marilyn Begole Chose Love ________8 Marilyn Begole declined an invitation to go to an important element of the town’s social and and soup. Often there would be a bean dish, New York and pursue a career in dancing. business life. A number of readers responded such as chili, prepared ahead of time. Maxe Reed Organ Donated to the Museum _ 9 including three who live in other parts of the Obermeyer recalls a line outside waiting A beautiful 1907 Ferrand reed organ was country. In our research we found that close to for a stool to open up. Joe’s Snappy Service recently donated to the Museum. 100 restaurants have opened and closed since would continue on Michigan Avenue until River Street Neighbor’s Gossip th and the Hutchinson Marriage _____10 the beginning of the 20 Century. We focused on the early seventies. -

Focus EMU, November 6, 1990

Produced�$ Volume 37, Number 15 Public Information Nov. 6, 1990 ]1�0CUS EMU and Publications Rebuilt Sherzer Hall back in fine form Only 19 months after 11 was near the start of tl:e 1990 fall semester. ly destroyed by fire, Sherzer Hall is The construction of the original back in fine form and was officially Sherzer Hall was funded by a rededicated Oct. 27 in ceremonies $55,000 appropriation from the attended by EMU President Michigan Legislature and was built William E. Shelton as part of on land donaced by the people of Homecoming/P'arents Day 1990. Ypsilanti. When it opened it was The historic 1903 structure was known as the Normal College nearly destroyed by fire March 9, Science Builc.ing and it wasn't until 1989, less than one month after the 1958, after the building underwent EMU Board of Regents approved a significant renovations, that it was program statement to submit to the renamed Sherzer Hall in honor of state for funding its renovation and Dr. William H. Sherzer, who serv restoration. Although considered ed as geology professor and head for demolition, a decision was of the NaturaJ Science Department made in April of that year to re at EMU from 1892 until his death build Sherzer to its original glory. in 1932. After the fire, approximately 50 Except for an astronomy class percent of the building remained in room and the observatory on the tact and more than 70 percent of fourth floor, the building is used the original exterior masonry shell exclusively for art instruction and remained, including the unique hosts offices for some art faculty members on the fourth floor. -

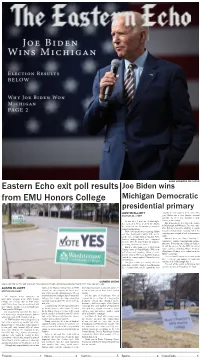

Eastern Echo Exit Poll Results from EMU Honors College

GAGE SKIDMORE ON FLICKR Eastern Echo exit poll results Joe Biden wins from EMU Honors College Michigan Democratic presidential primary AUSTIN ELLIOTT majority of rural counties in the state. This EDITOR-IN-CHIEF year, Biden was a clear favorite in rural counties. As of 1 a.m., Sanders is only At just after 9 p.m. on election night, leading in one county. the Associated Press declared Joe Biden Biden has also been declared the winner the winner of the Democratic presidential in Mississippi and Missouri. The wins come primary in Michigan. after Biden’s impressive showing in South With 100% of precincts reporting, Biden Carolina and on Super Tuesday, when his has won Washtenaw County with 47.6% campaign was catapulted back to frontrunner of the vote, leading Sanders who has 45%. status. Sanders underperformed here compared Biden’s wins on “Super Tuesday 2” to 2016, when he beat Clinton by about 12 tonight have solidified his frontrunner status, percentage points in the county. and some Democrats are calling for Sanders Biden is also doing very well in Kent to exit the race or for the DNC to cancel County, home of Grand Rapids. With over future debates, including House Majority half of precincts reporting, Biden is in the Whip James Clyburn, a key endorsement for lead by about 1,500 votes. In 2016, Sanders Biden’s campaign. carried the county against Clinton by over There are still 31 states and territories that 17,000 votes. have yet to vote, and primary elections will Tonight’s results were starkly different continue to be held through June 6.