Ives 2016 Spring Program Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margaret Madsen

Sunday, May 14, 2017 • 9:00 p.m Margaret Madsen Senior Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Sunday, May 14, 2017 • 9:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Margaret Madsen, cello Senior Recital SeungWha Baek, piano PROGRAM Mark O’Connor (b. 1961); arr. Mark O’Connor Appalachia Waltz (1993) Hans Werner Henze (1926-2012) Serenade (1949) Adagio rubato Poco Allegretto Pastorale Andante con moto, rubato Vivace Tango Allegro marciale Allegretto Menuett Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Theme and Variations for Solo Cello (1887) Intermission Samuel Barber (1910-1981) Cello Sonata, Op. 6 (1932) Adagio ma non troppo Adagio Allegro appassionato SeungWha Baek, piano Margaret Madsen • May 14, 2017 Program Johannes Brahms (1833-1897); arr. Alfred Piatti Hungarian Dances (1869) I. Allegro molto III. Allegretto V. Allegro; Vivace; Allegro SeungWha Baek, piano P.D.Q. Bach (1807-1742) Suite No. 2 for Cello All by Its Lonesome, S. 1b (1991) Preludio Molto Importanto Bourrée Molto Schmaltzando Sarabanda In Modo Lullabyo Menuetto Allegretto Gigue-o-lo Margaret Madsen is from the studio of Stephen Balderston. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Margaret Madsen • May 14, 2017 PROGRAM NOTES Mark O’Connor (b. 1961) Appalachia Waltz Duration: 4 minutes Besides recently becoming infamous for condemning the world-renowned late pedagogue Shinichi Suzuki as a fraud, Mark O’Connor is also known as an award-winning violinist, composer, and teacher. Despite growing up in Seattle, Washington, O’Connor always had a passion for Appalachian fiddling and folk tunes, winning competitions in fiddling, guitar, and mandolin as a teen and young adult. -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Ebony and Ivory—And Longevity a MASTER’S INFLUENCE REVERBERATES OVER SEVENTY-THREE YEARS at CURTIS

MEET THE FACULTY Ebony and Ivory—and Longevity A MASTER’S INFLUENCE REVERBERATES OVER SEVENTY-THREE YEARS AT CURTIS BY PETER DOBRIN Perched on the edge of a rocking chair with “Much better,” says Mrs. Sokoloff. a score opened before her, Eleanor Sokoloff This drill, the transfer of accumulated looks up into the air and shakes her head in knowledge from master to student, is time to the music. basically the one you hear in every studio “That’s a girl,” she says, her forceful alto at the Curtis Institute of Music. Except overpowering the Beethoven. “I could use that this master has been doing it longer a little more top. Ah. That makes all the than anyone else. difference in a phrase.” Much longer. Eleanor Sokoloff The French cuffs of Mrs. Sokoloff’s has held essentially the same job at the fifteen-year-old student glide over the world-renowned music conservatory Bösendorfer keyboard. And then Sokoloff for seventy-three years. stops her. If you count back to the first time she “Well …,” she says with distaste and walked through the doors as a frightened suspicion in her voice. “Why is that note seventeen-year-old student, Sokoloff, 95, so soft?” has been a presence at the school for nearly Yen Yu “Jenny” Chen tries it a eight decades. different way. “She was always here,” said former “No, that’s ugly. You know why? Curtis president Gary Graffman. It breaks the line.” “She’s kind of a colossal figure at Chen takes yet another stab at it. Curtis,” said Heather Connor, a student from 1992 to 1997. -

Barber–String Quartet

Samuel Barber (b. West Chester, PA, March 9, 1910; d. New York, NY, January 23, 1981) String Quartet, op. 11 (1936) Composed: 1936 Approximate duration: 16 minutes Since accompanying the radio announcement of President Franklin Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings has stood as arguably the most iconic work of American classical repertoire. As a compositional feat, the Adagio is nothing short of a minor miracle: melodically and harmonically concise, emotionally devastating. It epitomizes the fervent lyricism and expressive immediacy that have established Barber among the twentieth century’s most venerated American musical figures. While frequently performed in Barber’s version for string orchestra, the Adagio less often appears in its original form, as the second movement (marked Molto adagio) of his String Quartet, op. 11, composed in 1936. (Barber, nota bene, recognized what he had accomplished; on September 19 of that year, he wrote to the cellist Orlando Cole, “I have just finished the slow movement of my quartet today—it is a knockout! Now for a Finale.”) Yet its presentation in the context of the three-movement Quartet affords the listener a special opportunity. Played by just two violins, viola, and cello, the Adagio’s breathless lines burn with an intimate intensity muted by the quiet army of orchestral strings. Furthermore, framed by the Quartet’s outer movements—the angular Molto allegro e appassionato, and the concluding reprise of the first movement’s material—the ubiquitous slow movement takes on a more nuanced significance. For prefaced by the angular dissonance of the opening movement, the Adagio emerges as a response to worldly strife. -

2007-2008 Master Class-Orlando Cole (Cello)

UPCOMING EVENTS Tuesday, November 20 th STUDENT RECITALS 5:30 pm Valentin Mansurov , violinist, performs his Master of Music Recital with pianist, Tao Lin, Artist Faculty and Head of the Collaborative Piano Program. 7:30 pm Aziz Sapaev, cellist, performs his Junior Degree Recital in collaboration with pianist, Ni Peng, performing works of Bach, Beethoven and Haydn. Time: 5:30 pm and 7:30 pm Location: Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Tickets: FREE Tuesday, November 27 th STUDENT RECITALS 6:00 pm Nikola Nikolovski, trumpet player performs works of Hummel and Hansen in his Junior Recital. 7:30 pm Madeleine Leslie, double bassist, performs her Master of Music Recital performing works of Bottesini, Eccles and Saint Saëns. Time: 6:00 pm and 7:30 pm Location: Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Tickets: FREE Thursday, November 29 th STRING CONCERT #1 Treat yourself to an enjoyable evening of music featuring performances by Conservatory of Music string students. Hear violinists, violists, cellists and bassists chosen to showcase the conservatory’s outstanding strings department. Time: 7:30 p.m. Location: Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Tickets: $10 Tuesday, December 4th STUDENT RECITALS 6:00 pm Bud Holmes, tuba player, performs his Junior Recital with Yang Shen, collaborative pianist. 7:30 pm Oksana Rusina, cellist, performs her PPC Recital with pianist, Yang Shen. Time: 6:00 pm and 7:30 pm Location: Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall Tickets: FREE 2007 2008 Season CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC AT LYNN UNIVERSITY CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC AT LYNN UNIVERSITY 3601 N. Military Trail, When talent meets inspiration, Boca Raton, FL 33431 the results are extraordinary. -

ALBAN Gerhardt ANNE-Marie Mcdermott

THE KINDLER FOUNDATION TRUST FUND iN tHE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS ALBAN GERHARDT ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT Saturday, January 16, 2016 ~ 2 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building In 1983 the KINDLER FOUNDATION TRUST FUND in the Library of Congress was established to honor cellist Hans Kindler, founder and first director of the National Symphony Orchestra, through concert presentations and commissioning of new works. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Saturday, January 16, 2016 — 2 pm THE KINDLER FOUNDATION TRUST FUND iN tHE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS ALBAN GERHARDT, CELLO ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT, PIANO • Program SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) Sonata for cello and piano, op. 6 (1932) Allegro ma non troppo Adagio—Presto—Adagio Allegro appassionato BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) Sonata in C major for cello and piano, op. 65 (1960-1961) Dialogo Scherzo-pizzicato Elegia Marcia Moto perpetuo LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) Capriccio (1946) iNtermission 1 LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918-1990) Three Meditations from Mass for cello and piano (1971) Meditation no. -

May 1941) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 5-1-1941 Volume 59, Number 05 (May 1941) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 59, Number 05 (May 1941)." , (1941). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/250 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M . N»J " '** fifty jM( * 'H it' » f A f ’\Jf ? I» ***v ASCAP STATES ITS POLICY OF CO-OPERATION WITH ALL MUSIC EDUCATORS, ASSOCIATIONS, AND RELATED GROUPS: music educators, teachers, _, HERE HAS BEEN some misunderstanding upon the part of institutions, and others, music of our members has been withdrawn by ASCAP from use by X to the effect that the copyrighted educational and civic programs. This is not the fact. broadcasters in non-commercial religious, stations (network controlled) will not permit The radio networks and most of the important to be per- by any member of ASCAP, regardless of the nature of the formed on their airwaves, any music composed and presented by a church, school, club, civic group, or music program, even if entirely non-commercial, students or classes. -

Buffalo Chamber Music Society 1924-2019 Ensembles – Artists

BUFFALO CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY 1924-2019 ENSEMBLES – ARTISTS ACADEMY OF ST. MARTIN IN THE FIELDS, IONA BROWN, Director and violin soloist ACADEMY OF ST. MARTIN IN THE FIELDS OCTET Kenneth Sillito, violin, leader; Harvey de Souza, violin; Mark Butler, violin; Paul Ezergailis, violin Robert Smissen, viola; Duncan Ferguson, viola; Stephen Orton, cello; John Heley, cello AIZURI QUARTET Emma Frucht & Miho Saegusa, violins; Ayane Kozasa, viola; Karen Ouzounian, cello ; ALBENERI TRIO Alexander Schneider, violin; Benar Heifetz, cello; Erich Itor Kahn, piano – 1945, 1948 Giorgio Ciompi, violin; Benar Heifetz, cello; Erich Itor Kahn, piano 1951, 1952,1955 Giorgio Ciompi, violin; Benar Heifetz, cello, Ward Davenny, piano 1956, 1958 Giorgio Ciompi, violn; Benar Heifetz, cello; Arthur Balsam, piano 1961 ALEXANDER SCHNEIDER AND FRIENDS Alexander Schneider, violin; Ruth Laredo, piano; Walter Trampler, viola, Leslie Parnas, cello 1973 Alexander Schneider, violin; Walter Trampler, viola; Laurence Lesser, cello; Lee Luvisi, piano 1980 ALEXANDER STRING QUARTET Eric Pritchard, violin; Frederick Lifsitz, violin; Paul Yarbrough, viola; Sandy Wilson, cello 1988 Ge-Fang Yang, violin; Frederick Lifsitz, violin; Paul Yarbrough, viola; Sandy Wilson, cello 1994 Zakarias Grafilo, violin; Frederick Lifsitz, violin; Paul Yarbrough, viola; Sandy Wilson, cello 2006 ALMA TRIO Andor Toth, violin; Gabor Rejto, cello; Adolph Baller, piano 1967 Andor Toth, violin; Gabor Rejto, cello; William Corbett Jones, piano 1970 ALTENBERG TRIO Claus-Christian Schuster, piano; Amiram Ganz, -

Chambermusic

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Samuel Barber, circa 1960 The Some of the composer’s best-known Chamber works for small ensemble, written in his youth, entered the repertoire early and remained there. Music of by Barbara Heyman oncert audiences know Samuel Barber for his large-scale orchestral works—the Overture to The School for Scandal, Cthe violin and cello concertos, Knoxville: Summer of 1915, the symphonies, and the three Essays. His chamber music oeuvre is small, but some of these works remain favorites in the repertoire. String players revere the String Quartet in B Minor, Dover Beach, and the Cello Sonata. And wind players know that Barber’s penchant for writing solos for flute, clarinet, and oboe (his signature instrument) Samuel in orchestral works also expresses itself in such small-scale works as Summer Music, Capricorn Concerto, and the 1959 Elegy for Flute and Piano. In recent years I have been assembling a complete thematic catalog of Barber’s works, and in the process have come across some early, unpublished ensemble works that few are familiar with. Among these, the most important is certainly the third movement of Barber’s Sonata in F minor for Violin and Piano, rediscovered in 2006. Masquerading under the title page Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, the music turned up in the estate of the Barber Pennsylvania artist Tom Bostell, who had been a boarder in the Barber family’s West Chester, Pennsylvania, home. When asked to view the 17 pages of manuscript, I recognized the first three pages as those that were missing from the autograph manuscript of the Cello Sonata at the Library of Congress. -

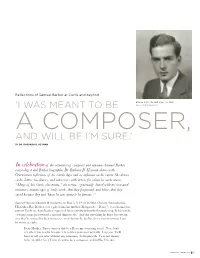

Reflections of Samuel Barber at Curtis and Beyond

Reflections of Samuel Barber at Curtis and beyond Barber in his student days, ca. 1932 ‘I WAS MEANT TO BE PHOTO: CURTIS ARCHIVES A COMPOSER, AND WILL BE I’M SURE.’ BY DR. BARBARA B. HEYMAN In celebration of the centenary of composer and alumnus Samuel Barber, musicologist and Barber biographer Dr. Barbara B. Heyman shares with Overtones reflections of his Curtis days and its influence on his career. She draws on his letters, his diaries, and interviews with artists for whom he wrote music. “Many of his Curtis classmates,” she writes, “generously shared with me treasured memories, manuscripts of early works that they performed, and letters that they saved because they just ‘knew he was going to be famous.’” Samuel Osmond Barber II was born on March 9, 1910, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father, Roy Barber, was a physician; his mother, Marguerite (“Daisy”), was an amateur pianist. Early on, Sam Barber expressed his creativity primarily through song. In his words, “writing songs just seemed a natural thing to do.” And the one thing he knew for certain was that he wanted to be a composer, an ambition he declared in a now-infamous letter he wrote at eight: Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don’t cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell you now without any nonsense. To begin with, I was not meant to be an athlet [sic]. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I’m sure. -

Wells School of Music

1 OUR HISTORY In 2019-2020, Tri-County Concerts Association proudly celebrates its 79th year as one of the region’s most significant venues for chamber music. In December 1941, chamber music in the Philadelphia area received a remarkable boost from Ellen Winsor and Rebecca Winsor Evans when the two sisters decided to sponsor the original Curtis String Quartet in a free public concert at Radnor Junior High School. An early program says that “its aim was to bring the spiritual peace and the beauty of music in the lives of our fellow-citizens who were living under the shadow of war; thus strengthening them with the knowledge that music is the great international language which unites all peoples in the common bond of friendship.” The musicians were enthusiastically received and the Tri-County Concerts Association was successfully launched. In 1943, the fledgling organization held its first Youth Music Festival and assumed a vital position in the area’s cultural life. From the early 1950s to the late 1970s, the driving force behind Tri-County Concerts was Guida Smith. Her energies were devoted to bringing top musical artists to the community, as well as relatively unknown virtuosi who later became internationally renowned. In 1979 Jean Wetherill of Radnor assumed leadership of the organization and fostered its continued health during a period of transition. That year, the Association became a nonprofit corporation in order to strengthen its mission and its increasingly important fundraising functions. When Radnor Middle School 80 Years of Unparalleled Opportunities underwent renovations in 1980, the concert series was relocated to Delaware County Community College. -

Rachmaninoff Barber

RACHMANINOFF ♦ BARBER CELLO SONATAS DE 3574 Jonah Kim, cello ♦ Sean Kennard, piano 1 DELOS DE 3574 DELOS DE 3574 RACHMANINOFF ♦ BARBER CELLO SONATAS JONAH KIM, CELLO ♦ SEAN KENNARD, PIANO ♦ SEAN KENNARD, JONAH KIM, CELLO JONAH KIM, CELLO ♦ SEAN KENNARD, PIANO ♦ SEAN KENNARD, JONAH KIM, CELLO RACHMANINOFF ♦ BARBER: CELLO SONATAS ♦ BARBER: CELLO RACHMANINOFF RACHMANINOFF ♦ BARBER: CELLO SONATAS ♦ BARBER: CELLO RACHMANINOFF Sergei Rachmaninoff 11 Sonata for Piano and Violoncello, Op. 19 11 eno llero moderao ● llero cherando ● ndane ● llero moo Samuel Barber 1111 Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, Op. 6 1 llero ma non roppo ● daio reo di noo daio ● llero appaionao Jonah Kim, cello ♦ Sean Kennard, piano Toal lain ime 1 DE 3574 © 2020 Delos Producti ons, Inc., P.O. Box 343, Sonoma, CA 95476-9998 (800) 364-0645 • (707) 996-3844 [email protected] • www.delosmusic.com RACHMANINOFF ♦ BARBER CELLO SONATAS Jonah Kim, cello ♦ Sean Kennard, piano Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Sonata for Piano and Violoncello, Op. 19 (1901) (33:06) 1. Lento; Allegro moderato (9:50) 2. Allegro scherzando (6:43) 3. Andante (5:55) 4. Allegro mosso (10:36) Samuel Barber (1910–1981) Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, Op. 6 (1932) (19:42) 5. Allegro ma non troppo (8:51) 6. Adagio; Presto; di nuovo Adagio (5:03) 7. Allegro appassionato (5:47) Total Playing Time: 52:51 8 Notes on the Program qualities of the cello featured in broad, rhapsodic strokes. Sean Kennard writes, Sergei Rachmaninoff, suffering from the “Rachmaninoff’s Sonata has achieved a critical attacks on his Symphony No. 1 af- universal reputation as one of the great- ter its premiere in 1897, fell into a deep est and most difficult works in its genre.” depression and stopped composing al- together.