Samuel Barber's Contribution to Twentieth-Century Violoncello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

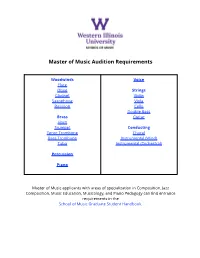

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Margaret Madsen

Sunday, May 14, 2017 • 9:00 p.m Margaret Madsen Senior Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Sunday, May 14, 2017 • 9:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Margaret Madsen, cello Senior Recital SeungWha Baek, piano PROGRAM Mark O’Connor (b. 1961); arr. Mark O’Connor Appalachia Waltz (1993) Hans Werner Henze (1926-2012) Serenade (1949) Adagio rubato Poco Allegretto Pastorale Andante con moto, rubato Vivace Tango Allegro marciale Allegretto Menuett Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Theme and Variations for Solo Cello (1887) Intermission Samuel Barber (1910-1981) Cello Sonata, Op. 6 (1932) Adagio ma non troppo Adagio Allegro appassionato SeungWha Baek, piano Margaret Madsen • May 14, 2017 Program Johannes Brahms (1833-1897); arr. Alfred Piatti Hungarian Dances (1869) I. Allegro molto III. Allegretto V. Allegro; Vivace; Allegro SeungWha Baek, piano P.D.Q. Bach (1807-1742) Suite No. 2 for Cello All by Its Lonesome, S. 1b (1991) Preludio Molto Importanto Bourrée Molto Schmaltzando Sarabanda In Modo Lullabyo Menuetto Allegretto Gigue-o-lo Margaret Madsen is from the studio of Stephen Balderston. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Margaret Madsen • May 14, 2017 PROGRAM NOTES Mark O’Connor (b. 1961) Appalachia Waltz Duration: 4 minutes Besides recently becoming infamous for condemning the world-renowned late pedagogue Shinichi Suzuki as a fraud, Mark O’Connor is also known as an award-winning violinist, composer, and teacher. Despite growing up in Seattle, Washington, O’Connor always had a passion for Appalachian fiddling and folk tunes, winning competitions in fiddling, guitar, and mandolin as a teen and young adult. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Barber Piano Sonata In E-flat Minor, Opus 26 Comparative Survey: 29 performances evaluated, September 2014 Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) is most famous for his Adagio for Strings which achieved iconic status when it was played at F.D.R’s funeral procession and at subsequent solemn occasions of state. But he also wrote many wonderful songs, a symphony, a dramatic Sonata for Cello and Piano, and much more. He also contributed one of the most important 20th Century works written for the piano: The Piano Sonata, Op. 26. Written between 1947 and 1949, Barber’s Sonata vies, in terms of popularity, with Copland’s Piano Variations as one of the most frequently programmed and recorded works by an American composer. Despite snide remarks from Barber’s terminally insular academic contemporaries, the Sonata has been well received by audiences ever since its first flamboyant premier by Vladimir Horowitz. Barber’s unique brand of mid-20th Century post-romantic modernism is in full creative flower here with four well-contrasted movements that offer a full range of textures and techniques. Each of the strongly characterized movements offers a corresponding range of moods from jagged defiance, wistful nostalgia and dark despondency, to self-generating optimism, all of which is generously wrapped with Barber’s own soaring lyricism. The first movement, Allegro energico, is tough and angular, the most ‘modern’ of the movements in terms of aggressive dissonance. Yet it is not unremittingly pugilistic, for Barber provides the listener with alternating sections of dreamy introspection and moments of expansive optimism. The opening theme is stern and severe with jagged and dotted rhythms that give a sense of propelling physicality of gesture and a mood of angry defiance. -

A Performer's Guide to Hertl's Concerto for Double Bass

A Performer's Guide To Frantisek Hertl's Concerto for Double Bass Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Roederer, Jason Kyle Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 15:16:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194487 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HERTL’S CONCERTO FOR DOUBLE BASS by Jason Kyle Roederer ________________________ Copyright © Jason Kyle Roederer 2009 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Jason Kyle Roederer entitled A Performer’s Guide to Hertl’s Concerto for Double Bass and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Patrick Neher _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Mark Rush _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Thomas Patterson Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition Edward Charity Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Summer 6-30-2014 Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition Edward Charity Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Charity, Edward, "Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition" (2014). Research Papers. Paper 551. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/551 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION by Edward Charity B.M., Northwestern State University, 2011. A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale August 2014 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION By Edward Charity A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Performance Approved by: Michael Barta, Chair Eric Lenz Jacob Tews Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale June 28, 2014 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Edward Charity, for the Master of Music degree in Music Performance, presented on June 30, 2014, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION MAJOR PROFESSOR: Michael Barta Three seminal works of the violin repertory will be examined: J.S. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973)