Defender of the Gate: the Presidio of San

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclassified U.S

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Navy Master at Arms 1st Class Ekali Brooks (R) coordinates with a U.S. Soldier to provide security while he and his dog Bak search for explosives in nearby classrooms, Sep. 10, 2008. Iraqi soldiers and U.S. Troops from 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, and Bravo Company, 52nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 25th Infantry Division conducted a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, to provide medical treatment to the local Iraqi people. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Daniel Herrera/Released) 080910-A-8725H-220 UNCLASSIFIED An Iraqi soldier interacts with local children, Sep. 10, 2008. Iraqi soldiers and U.S. Troops from 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, and Bravo Company, 52nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, conducted a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, to provide medical treatment to the local Iraqi people. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Daniel Herrera/Released) 080910-A-8725H-502 UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Army Sgt. Susan McGuyer, 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, searches Iraqi women before they can be treated by medical personnel, Sep. 10, 2008. Iraqi soldiers and U.S. Troops from 2nd Squadron, 14th Cavalry Regiment, and Bravo Company, 52nd Anti-Tank Regiment, 25th Infantry Division conducted a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, to provide medical treatment to the local Iraqi people. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Daniel Herrera/Released) 080910-A-8725H-335 UNCLASSIFIED Iraqi soldiers conduct a cooperative medical engagement at a local elementary school in Hor Al Bosh, Iraq, Sep. -

Citizenship: ‘It’S Like Being Reborn’ Play Dual Role Tary

The Expeditionary Times Proudly serving the finest Expeditionary service members throughout Iraq Vol. 4 Issue 27 November 17, 2010 www.armyreserve.army.mil/103rdESC Flip-Flops A 6th grade class donates sandals Page 5 Teachers U.S. Army photo by Lee Craker, United States Forces-Iraq Public Affairs Office Spc. Jehan Custodio Martinez, a supply clerk with the 1st Squadron, 6th Cavalry Regiment, receives a congratulatory hug from another service member after becoming a U.S. citizen. United States Forces-Iraq held a Naturalization Ceremony on Veterans Day in the Al Faw Palace at Camp Vic- tory, Iraq, and 50 service members took the Oath of Allegiance to became U.S. citizens. Service members Citizenship: ‘It’s like being reborn’ play dual role tary. Roland Lefevre, a light vehicle mechanic with STORY BY SPC. ZANE CRAIG “I feel like I’m officially part of the family A Company, 199th Brigade Support Battalion, Page 6 EXPEDITIONARY TIMES STAFF now,” said Spc. Michelle Canas, a supply 224th Sust. Bde., 103rd ESC, and a Paris, clerk with the 110th Combat Services Support France, native. VICTORY BASE COMPLEX, Iraq— Fifty Battalion, 224th Sustainment Brigade, 103rd Five Soldiers with units under the 103rd ESC U.S. service members from Sustainment Command (Expeditionary). Canas took the Oath of Citizenship: Canas; Lefevre; 21 different countries became is originally from the Philippines but has lived in Sgt. Mallcom Rochelle with A Co. 199th BSB; JAG 5K United States Citizens at the Georgia since 2004. Staff Sgt. Louis Greaves with the 110th Combat United States Forces-Iraq “I feel like it means a lot more to be natural- Sustainment Support Battalion, 224th Sust. -

The Historical Sketch & Roster Series

1 The Historical Sketch & Roster Series These books contain information for researching the men who served in a particular unit. The focus is for genealogical rather than historical research. TABLE OF CONTENTS: List of Officers with biographical sketches List of companies and the counties where formed Officers of each company Military assignments Battles engaged in the war Historical sketch of the regiment's service Rosters / compiled service records of each company Bibliography of sources Hardback - $45.00 (SPECIAL ORDER. ALLOW 6 WEEKS FOR DELIVERY) Paperback - $25.00 CD-ROM - $15.00 EBOOK - $12.95 – PDF format of the book delivered by EMAIL – NO SHIPPING CHARGE Shipping is $5.00 per order regardless of the number of titles ordered. Order From: Eastern Digital Resources 5705 Sullivan Point Drive Powder Springs, GA 30127 (803) 661-3102 Order on Line http://www.researchonline.net/catalog/crhmast.htm [email protected] 2 Alabama Historical Sketch and Roster Series 85 Volumes Total - Set Price Hardback $3195.00 1st Battalion Alabama 10th Infantry Regiment 36th Infantry Regiment Cadets 11th Cavalry Regiment 37th Infantry Regiment 1st Infantry Regiment 11th Infantry Regiment 38th Infantry Regiment 1st Mobile Infantry 12th Cavalry Regiment 39th Infantry Regiment 1st Cavalry Regiment 12th Infantry Regiment 40th Infantry Regiment 2nd Artillery Battalion 13th Infantry Regiment 41st Infantry Regiment 2nd Cavalry Regiment 14th Infantry Regiment 42nd Infantry Regiment 2nd Infantry Regiment 15th Battalion 43rd Infantry Regiment 2nd Regiment -

Ohio Historical Newspapers by Region

OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSPAPER INDEX UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES, WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY Alphabetical by Region Arcanum Arcanum Time (weekly) May 11, 1899 - Jan 2, 1902 Aug. 27, 1903 - Dec. 20, 1905 April 26, 1906 – Dec. 22, 1910 May 2, 1912 – Jan 19, 1950 April 20, 1950 – Feb 9, 1961 Oct. 18 – 25, 1962 Darke Times Feb 16, 1961 – Dec 27, 1962 June 6, 1968 – Jan 23, 1969 July 3, 1969 –June 26, 1970 Early Bird (weekly) Nov 1, 1971- May 3,1977 Nov 16, 1981- Dec 27,1993 Early Bird Shopper June 2, 1969 – Oct 25,1971 Bath Township BZA Minutes 1961-1973 Trustees Minutes v.1 – 13 1849 – 1869 1951 – 1958 Beavercreek Beavercreek Daily News 1960-1962 1963 -1964 Jan 1975 – June 1978 March 1979 – Nov 30, 1979 Beavercreek News Jan 1965 – Dec 1974 Bellbrook Bellbrook Moon Sept 14, 1892 – June 23, 1897 Bellbrook-Sugarcreek Post May 19, 1965 – April 7, 1971 Bellefontaine Bellefontaine Gazette Feb 25, 1831 – Feb 29, 1840 Bellefontaine Gazette and Logan Co. Advertiser Jan 30, 1836 – Sept 16, 1837 Bellefontaine Republican Oct. 27,1854 – Jan 2 1894 Feb 26, 1897 – June 3, 1898 Sept. 28, 1900 – May 29, 1904 Bellefontaine Republican and Logan Register July 30, 1830 – Jan 15, 1831 Logan County Gazette June 9, 1854 – June 6, 1857 June 9, 1860 – Sept 18, 1863 Logan County Index Nov 19, 1885 – Jan 26, 1888 Logan Democrat Jan 4, 1843 – May 10, 1843 Logan Gazette Apr 4, 1840 – Mar 6, 1841 Jun 7, 1850 – Jun 4, 1852 Washington Republican and Guernsey Recorder July 4, 1829 – Dec 26, 1829 Weekly Examiner Jan 5, 1912 – Dec 31, 1915 March -

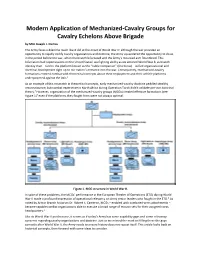

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J. Dumas The Army faces a dilemma much like it did at the onset of World War II: although the war provided an opportunity to rapidly codify cavalry organizations and doctrine, the Army squandered the opportunity to do so in the period before the war, when the branch bifurcated and the Army’s mounted arm floundered. This bifurcation had repercussions on the United States’ warfighting ability as we entered World War II, as branch identity then – tied to the platform known as the “noble companion” (the horse) – stifled organizational and doctrinal development right up to our nation’s entrance into the war. Consequently, mechanized-cavalry formations entered combat with theoretical concepts about their employment and their vehicle platforms underpowered against the Axis.1 As an example of this mismatch in theoretical concepts, early mechanized-cavalry doctrine peddled stealthy reconnaissance, but combat experience in North Africa during Operation Torch didn’t validate pre-war doctrinal theory.2 However, organization of the mechanized-cavalry groups (MCGs) created effective formations (see Figure 1)3 even if the platforms they fought from were not always optimal. Figure 1. MCG structure in World War II. In spite of these problems, the MCGs’ performance in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during World War II made a profound impression of operational relevancy on Army senior leaders who fought in the ETO.4 As noted by Armor Branch historian Dr. Robert S. Cameron, MCGs – enabled with combined-arms attachments – became capable combat organizations able to execute a broad range of mission sets for their assigned corps headquarters.5 Like its World War II predecessor, it seems as if today’s Army has some capability gaps and some relevancy concerns regarding cavalry organizations and doctrine. -

Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park 4011 Grant Drive Earlimart, CA 93219 (661) 849-3433

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is Colonel to provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping n 1908 a group of to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological I Allensworth diversity, protecting its most valued natural and African Americans cultural resources, and creating opportunities State Historic Park for high-quality outdoor recreation. led by Colonel Allen Allensworth founded a town that would combine pride of ownership, California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who equality of opportunity, need assistance should contact the park at (661) 849-3433. If you need this publication in an and high ideals. alternate format, contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park 4011 Grant Drive Earlimart, CA 93219 (661) 849-3433 © 2007 California State Parks (Rev. 2017) I n the southern San Joaquin Valley, music teacher, and the colony of Allensworth a modest but growing assemblage of gifted musician, began to rise from the flat restored and reconstructed buildings marks and they raised two countryside — California’s the location of Colonel Allensworth State daughters. In 1886, first town founded, financed, Historic Park. A schoolhouse, a Baptist church, with a doctorate of and governed by businesses, homes, a hotel, a library, and theology, Allensworth African Americans. various other structures symbolize the rebirth became chaplain to The name and reputation of one man’s dream of an independent, the 24th Infantry, one of Colonel Allensworth democratic town where African Americans of the Army’s four inspired African Americans could live in control of their own destiny. -

Annotated Bibliography -- Trailtones

Annotated Bibliography -- Trailtones Part Three: Annotated Bibliography Contents: Abdul, Raoul. Blacks in Classical Music. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1977. [Mentions Tucson-born Ulysses Kay and his 'New Horizons' composition, performed by the Moscow State Radio Orchestra and cited in Pravda in 1958. His most recent opera was Margeret Walker's Jubilee.] Adams, Alice D. The Neglected Period of Anti-Slavery n America 1808-1831. Gloucester, Massachusetts: Peter Smith, 1964. [Charts the locations of Colonization groups in America.] Adams, George W. Doctors in Blue: the Medical History of the Union Army. New York: Henry Schuman, 1952. [Gives general information about the Civil War doctors.] Agee, Victoria. National Inventory of Documentary Sources in the United States. Teanack, New Jersey: Chadwick Healy, 1983. [The Black History collection is cited . Also found are: Mexico City Census counts, Arizona Indians, the Army, Fourth Colored Infantry, New Mexico and Civil War Pension information.] Ainsworth, Fred C. The War of the Rebellion Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. General Index. [Volumes I and Volume IV deal with Arizona.] Alwick, Henry. A Geography of Commodities. London: George G. Harrop and Co., 1962. [Tells about distribution of workers with certain crops, like sugar cane.] Amann, William F.,ed. Personnel of the Civil War: The Union Armies. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1961. [Gives Civil War genealogy of the Black Regiments that moved into Arizona from the United States Colored troops.] American Folklife Center. Ethnic Recordings in America: a Neglected Heritage. Washington: Library of Congress, 1982. [Talks of the Black Sacred Harping Singing, Blues & Gospel and Blues records of 1943- 66 by Mike Leadbetter.] American Historical Association Annual Report. -

Visions of Vietnam

DATA BOOK STAKES RESULTS European Pattern 2008 : HELLEBORINE (f Observatory) 3 wins at 2, wins in USA, Mariah’s Storm S, 2nd Gardenia H G3 . 277 PARK HILL S G2 Prix d’Aumale G3 , Prix Six Perfections LR . 280 DONCASTER CUP G2 Dam of 2 winners : 2010 : (f Observatory) 2005 : CONCHITA (f Cozzene) Winner at 3 in USA. DONCASTER. Sep 9. 3yo+f&m. 14f 132yds. DONCASTER. September 10. 3yo+. 18f. 2006 : Towanda (f Dynaformer) 1. EASTERN ARIA (UAE) 4 9-4 £56,770 2nd Dam : MUSICANTI by Nijinsky. 1 win in France. 1. SAMUEL (GB) 6 9-1 £56,770 2008 : WHITE MOONSTONE (f Dynaformer) 4 wins b f by Halling - Badraan (Danzig) Dam of DISTANT MUSIC (c Distant View: Dewhurst ch g by Sakhee - Dolores (Danehill) at 2, Meon Valley Stud Fillies’ Mile S G1 , O- Sheikh Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum S G1 , 3rd Champion S G1 ), New Orchid (see above) O/B- Normandie Stud Ltd TR- JHM Gosden Keepmoat May Hill S G2 , germantb.com Sweet B- Darley TR- M Johnston 2. Tastahil (IRE) 6 9-1 £21,520 Solera S G3 . 2. Rumoush (USA) 3 8-6 £21,520 Broodmare Sire : QUEST FOR FAME . Sire of the ch g by Singspiel - Luana (Shaadi) 2009 : (f Arch) b f by Rahy - Sarayir (Mr Prospector) dams of 24 Stakes winners. In 2010 - SKILLED O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Darley TR- BW Hills 2010 : (f Tiznow) O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Shadwell Farm LLC Commands G1, TAVISTOCK Montjeu G1, SILVER 3. Motrice (GB) 3 7-12 £10,770 TR- MP Tregoning POND Act One G2, FAMOUS NAME Dansili G3, gr f by Motivator - Entente Cordiale (Affirmed) 2nd Dam : DESERT STORMETTE by Storm Cat. -

Presidio of San Francisco an Outline of Its Evolution As a U.S

Special History Study Presidio of San Francisco An Outline of Its Evolution as a U.S. Army Post, 1847-1990 Presidio of San Francisco GOLDEN GATE National Recreation Area California NOV 1CM992 . Special History Study Presidio of San Francisco An Outline of Its Evolution as a U.S. Army Post, 1847-1990 August 1992 Erwin N. Thompson Sally B. Woodbridge Presidio of San Francisco GOLDEN GATE National Recreation Area California United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Denver Service Center "Significance, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder" Brian W. Dippie Printed on Recycled Paper CONTENTS PREFACE vii ABBREVIATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNINGS, 1846-1861 5 A. Takeover 5 B. The Indians 8 C. The Boundaries 9 D. Adobes, Forts, and Other Matters 10 CHAPTER 2: CIVIL WAR, 1861-1865 21 A. Organizing 21 B. Keeping the Peace 22 C. Building the Post 23 CHAPTER 3: THE PRESIDIO COMES OF AGE, 1866-1890 31 A. Peacetime 31 B. The Division Comes to the Presidio 36 C. Officers' Club, 20 46 D. Other Buildings 47 E. Troop Duty 49 F. Fort Winfield Scott 51 CHAPTER 4: BEAUTIFICATION, GROWTH, CAMPS, EARTHQUAKE, FORT WINFIELD SCOTT, 1883-1907 53 A. Beautification 53 B. Growth 64 C. Camps and Cantonments 70 D. Earthquake 75 E. Fort Winfield Scott, Again 78 CHAPTER 5: THE PRESIDIO AND THE FORT, 1906-1930 81 A. A Headquarters for the Division 81 B. Housing and Other Structures, 1907-1910 81 C. Infantry Terrace 84 D. Fires and Firemen 86 E. Barracks 35 and Cavalry Stables 90 F. -

Interview No. 605

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Combined Interviews Institute of Oral History 6-1982 Interview no. 605 Joseph Magoffin Glasgow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/interviews Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Interview with Joseph Magoffin Glasgowy b Sarah E. John, 1982, "Interview no. 605," Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Oral History at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Combined Interviews by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U!HVERS lTV OF T::::XAS .IIT EL P,~S') PISTITUTE OF '1Rfl HISTORY I,lTCRVIE;JEE: Col. Joseph Magoffin Glasgow (1898-1985) IiHERVIEUER: Sarah E. John P:~OJ[CT: Military History June-October. 1982 TER[<S OF USE: Unrestricted TAPE W).: 605 i'Rl\llSCRIPT ,'10.: 605 ':<;:11,15 C!~I !JER: Georgina Rivas and Marta l~cCarthy February-March. 1983 I;· I()(:f(I\P:1W~L svnops IS OF IiiTER\!I FlEE: (Member of pioneer El Paso family; retired Army colonel) Born September 28.1898 at the Maqoffin Homestead in E1 Paso; parents were Viilliam Jefferson Glasgow. a U.S. Cavalry officer. and Josephine Richardson Magoffin; attended elementary school in El Paso. private school in Kansas. and Viest Point; 0raduated from Viest Point in November. 1918. SU if ,MY OF WTERVIE"I: TAPE I: Biographical data; childhood recollections and early El Paso; moving around the country with his family; how he came to enter Viest Point; experiences as part of the Army of Occupation in Europe following World Viar I; brief histories of the Magoffin and Glasgow families. -

Haras La Pasion

ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE GANADORES CLÁSICOS REFERENCIA DE PADRILLOS EASING ALONG VIOLENCE MANIPULATOR LIZARD ISLAND SIXTIES ICON ZENSATIONAL SANTILLANO SABAYON HURRICANE CAT JOHN F KENNEDY GALAN DE CINE POTRILLOS POTRANCAS NOTAS CÓMO LLEGAR ÍNDICE POTRILLOS POTRILLOS 1 ES CALIU Easing Along - Entidad Suprema por Rock Hard Ten 2 EL IMPENETRABLE Violence - La Imparcial por Easing Along 3 VITARO Violence - Vlytava por Southern Halo 4 PADRICIANO Violence - Petrova por Southern Halo 5 BOLLANI Manipulator - Be My Baby por Exchange Rate 6 LEONCINO Manipulator - Latoscana por Sea The Stars 7 ONDEADOR Manipulator - Onda Chic por Easing Along 8 ARDE DENTRO Manipulator - Arde La Ciudad por Stormy Atlantic 9 LINCE IBERICO Manipulator - Linkwoman por Southern Halo 10 FANATICO MISTICO Manipulator - Fancy Kitty por Easing Along 11 MUY SARDINERO Manipulator - Monaguesca por Easing Along 12 DON BERTONI Manipulator - Dayli por Mutakddim 13 ANANA FIZZ Manipulator - Anantara por Exchange Rate 14 MUÑECO VUDU Manipulator - Muñeca Lista por Lizard Island 15 CARROBBIO Lizard Island - Cookie Crisp por Mutakddim 16 SAN DOMENICO Lizard Island - Saratogian por Candy Ride 17 ENTRE VOS Y YO Sixties Icon - Entretiempo por Exchange Rate 18 SAGARDOY Sixties Icon - Sagardoa por Easing Along 19 CILINDRO Sixties Icon - Cilindrada por Touch Gold 20 DON BASSI Sixties Icon - Devotion Unbridled por Unbridled 21 ILUMINISMO Sixties Icon - Ilegalidad por Easing Along 22 BUEN BELGA Zensational - Buenas Costumbres por Honour And Glory 23 LEON AMERICANO Zensational - Leandrinha por Bernstein -

APRIL, 1900. 12.1 October

APRIL,1900. MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW. 155 River, suffered many vicissitudes. There was frost almost age difference between the wind force at the two situations is so remarkable that it may be of interest to give, without further delay, every night, and the average temperature waa only 35O, being the monthly mean values of wind velocity during 1699, at the respect- the coldest for thirty years. On the loth, the anniversary of ive stations. the blizzard of 1888, the minimum was only 2O above zero. The "head" of the Dines instrument at Hesketh Park is 36 feet A vivid picture of the ice storm that prevailed during the above the summit of the highest hill or knoll in the town, and 26 feet above the top of the roof of the Fernley structure, by which the knoll 1617th is published by Mrs. Britton, the wife of the director is capped. It is 85 feet above mean sea level. Some further idea of of the garden, in the first volume of the journal of the New its exposure and surroundings may be obtained from an inspection of York Botanical Garden. She stlys : the frontispiece to the annual report for 1897. The " head " of the Dines anemometer at Marshside is 50 feet above Notwithstanding the cold aeather of the month, there have been very level ground, and 40 feet above the roof of the brick hut. It is warm, quiet days and abundant signsof spring. The hylas were peep- 66 feet above mean sea level. In this case there is a very open expo- ing and the snow-drops were blooming in the nurseries on the loth, sure, and a large majority of winds reach the instrument without hav- and robins, meadow-larks, and song-sparrows had been singing.