Spatial Variation and Factors Impacting Grassland Circulation Price in Inner Mongolia, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanity Space Issn 2226-0773

HUMANITY SPACE ISSN 2226-0773 INTERNATIONAL ALMANAC HUMANITY SPACE MIKHAIL L. DANILEVSKY AND MEI-YING LIN A contribution to the study of China Dorcadionini (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) Parts 1-2 Volume 1, Supplement 4 MOSCOW 2012 Humanity space International almanac VOL. 1, Supplement 4, 2012: 4-19 A contribution to the study of China Dorcadionini (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae). Part 1. Mikhail L. Danilevsky1 and Mei-Ying Lin2 1A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninsky prospect 33, Moscow 119071 Russia. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1 # Beichen West Road, Chaoyang, Beijing, 100101, China. E-mail: [email protected] Key words: Cerambycidae, Lamiinae, Eodorcadion, taxonomy, China, Mongolia. Summary. The species rank E. rubrosuturale (Breuning, 1943) is restored. Several local populations of E. chinganicum (Suvorov, 1909) and E. rubrosuturale are partly described. Most of localities were never published before, so new distributional records are proposed for several taxa. Specimens from about all new localities are figured. Two names are downgraded to subspecies rank: E. chinganicum mandschukuoense (Breuning, 1944), stat. nov. and E. chinganicum darigangense Heyrovský, 1967, stat. nov. The taxon described as E. chinganicum kerulenum Danilevsky, 2007 is regarded as E. rubrosuturale kerulenum Danilevsky, 2007. INTRODUCTION A complete revision of the genus was published not long ago (Danilevsky, 2007) on the base of materials from Russian and West European Museums and collectors. Several specimens were also studied in National Museum of Natural History, Washington, USA. Unfortunately no materials were available from Chinese Museums, neither from Mongolian. -

40634-013: Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Environment

Initial Environmental Examination April 2013 Loan Number 2658-PRC People’s Republic of China: Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Environment Improvement Project (Phase II – Scope Change) Prepared by the Government of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region for Asian Development Bank This is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Inter-bank average exchange rate as of November 2012) Currency Unit - Yuan (CNY) CNY 1.00 = US$ 0.1587 USD 1.00 = 6.30 CNY For the purpose of calculations in this report, an exchange rate of $1.00 = 6.30 CNY has been used. ABBREVIATIONS ACM Asbestos-containing materials ADB Asian Development Bank AERMOD American Meteorological Society and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Regulatory Mod el AP Affected Person ASL Above sea level CEIA Consolidated Environmental Impact Assessment CFB Circulating Fluidized Bed CHP Combined Heat and Power CNY Chinese Yuan CSC Construction Supervision Company DCS Distributed Control System DI Design Institute EA Executing Agency EHS Environment, Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EMS Environmental Monitoring Station EMU Environmental Management Unit EPB Environmental Protection Bureau ESP Electrostatic precipitators FGD Flue Gas Desulfurization FSR Feasibility Study Report GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green House Gas GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism HES Heat Exchange Station HSP -

Involving Local Communities in Natural Resource Management: Xilingol Biosphere Reserve

INVOLVING LOCAL COMMUNITIES IN NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT: XILINGOL BIOSPHERE RESERVE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Geography, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Canada By Yijun Zhang © Copyright Yijun Zhang, February 2007. All Rights Reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate Degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department of the Dean of the College of Arts in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copy or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Geography University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to assess natural resource management practices in Xilingol Biosphere Reserve (XBR) located in northern China in their institutional contexts. -

Ethnic Minority Rights

ETHNIC MINORITY RIGHTS Findings • During the Commission’s 2019 reporting year, the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department continued to promote ethnic affairs work at all levels of Party and state governance that emphasized the importance of ‘‘sinicizing’’ eth- nic and religious minorities. Officials emphasized the need to ‘‘sinicize’’ the country’s religions, including Islam. Official ‘‘sinicization’’ efforts contributed to the increasing marginalization of ethnic minorities and their cultures and lan- guages. • Reports indicate that official efforts to repress Islamic prac- tices in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) have spread beyond the XUAR to Hui communities living in other locations. Developments suggest officials may be starting to carry out religious repression in areas outside of the XUAR that are modeled on restrictions already implemented within the XUAR. In November 2018, official media reported that Zhang Yunsheng, Communist Party official of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, had signed a counterterrorism agreement with XUAR officials during a trip to the XUAR to learn about its efforts to fight terrorism, maintain ‘‘social stability,’’ and manage religious affairs. • During the reporting year, authorities carried out the phys- ical destruction and alteration of Hui Muslim spaces and struc- tures, continuing a recent trend away from relative toleration of Hui Muslim faith communities. Officials demolished a mosque in a Hui community in Gansu province, raided and closed several mosques in Hui areas in Yunnan province, closed an Arabic-language school serving Hui students in Gansu, and carried out changes such as removing Arabic sign- age in Hui areas. These changes narrowed the space for Hui Muslim believers to assert an ethnic and religious identity dis- tinct from that of the dominant Han Chinese population. -

ESC Paper Style

Proceedings of the Trans-disciplinary Research Conference: Building Resilience of Mongolian Rangelands, Ulaanbaatar Mongolia, June 9-10, 2015 Modeling System Dynamics in Rangelands of the Mongolian Plateau Ginger R.H. Allington1,2, Wei Li1,3 Daniel G. Brown1,4 1School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, USA 2<[email protected]> 3<[email protected]> 4<[email protected]> ABSTRACT The rangelands of the Mongolian Plateau are dynamic social-ecological systems that are influenced by a complex network of drivers, including climate, social institutions, market forces and broad scale policies affecting land tenure. These factors are linked via feedbacks and often exhibit non-linear relationships. The sustainability and resilience of rangelands in this region are dependent on the ability of residents and policy makers to respond to changes and uncertainties regarding climate, socio-economic conditions, and land use. However, the complex nature of these systems makes it difficult to predict how changes in one aspect of the system will affect the functioning of other areas. We developed a system dynamics model to understand how the human, natural, and land-use systems in one part of the Mongolian rangeland ecosystem interact to produce dynamic outcomes in both grassland productivity and livestock population dynamics. An important contribution of this integrative model is to serve as a structure for synthesizing disparate data and models generated in several previous studies. It also provides a baseline for exploring future uncertainties and system dynamics in ways that can then be communicated back to stakeholders in the region. We present results from the model simulations of how ecosystem function and socioeconomic outcomes might change under alternative plausible climate, socioeconomic, and land use futures. -

Temporal and Spatial Distribution Characteristics in the Natural Plague

Du et al. Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2017) 6:124 DOI 10.1186/s40249-017-0338-7 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics in the natural plague foci of Chinese Mongolian gerbils based on spatial autocorrelation Hai-Wen Du1,2, Yong Wang1*, Da-Fang Zhuang1 and Xiao-San Jiang2* Abstract Background: The nest flea index of Meriones unguiculatus is a critical indicator for the prevention and control of plague, which can be used not only to detect the spatial and temporal distributions of Meriones unguiculatus, but also to reveal its cluster rule. This research detected the temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of the plague natural foci of Mongolian gerbils by body flea index from 2005 to 2014, in order to predict plague outbreaks. Methods: Global spatial autocorrelation was used to describe the entire spatial distribution pattern of the body flea index in the natural plague foci of typical Chinese Mongolian gerbils. Cluster and outlier analysis and hot spot analysis were also used to detect the intensity of clusters based on geographic information system methods. The quantity of M. unguiculatus nest fleas in the sentinel surveillance sites from 2005 to 2014 and host density data of the study area from 2005 to 2010 used in this study were provided by Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Results: The epidemic focus regions of the Mongolian gerbils remain the same as the hot spot regions relating to the body flea index. High clustering areas possess a similar pattern as the distribution pattern of the body flea index indicating that the transmission risk of plague is relatively high. -

Project List-201909.Xlsx

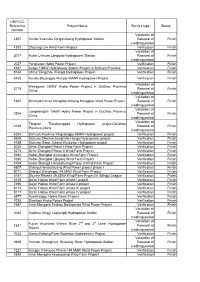

UNFCCC Reference Project Name Service type Status Number Validation of 1857 Hunan Yuanshui Qingshuitang Hydropower Station Renewal of Finish crediting period 1837 Zhejiang Cixi Wind Farm Project Verification Finish Validation of 2017 Hubei Lichuan Longqiao Hydropower Station Renewal of Finish crediting period 2037 Yangliutan Hydro Power Project Verification Finish 4287 Luogu 10MW Hydropower Station Project in Sichuan Province Verification Finish 8164 China Yongzhou Xiangqi Hydropower Project Verification Finish 4425 Hunan Shuangpai Wulipai 45MW Hydropower Project Verification Finish Validation of Wengyuan 20MW Hydro Power Project in Guizhou Province 2178 Renewal of Finish China. crediting period Validation of 1865 Sinohydro Inner Mongolia Ximeng Honggeer Wind Power Project Renewal of Finish crediting period Validation of Longwangtan 15MW Hydro Power Project in Guizhou Province 2204 Renewal of Finish China crediting period Validation of Tongren Tianshengqiao Hydropower project,Guizhou 2136 Renewal of Finish Province,China crediting period 6204 Sichuan Province Yingxiongpo 56MW Hydropower project Verification Finish 4609 Sichuan Shimian Songlinhe Hongyi Hydropower project Verification Finish 4729 Sichuan Ganzi Jiulong Wuyiqiao Hydropower project Verification Finish 4046 Dehe Zhangbei Phase I Wind Farm Project Verification Finish 5275 Dehe Zhangbei Phase II Wind Farm Project Verification Finish 5284 Hebei Zhangbei Xishungou Wind Farm Project Verification Finish 5285 Hebei Zhangbei Lijiaying Wind Farm Project Verification Finish 4769 Hebei -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Inner Mongolia

Access China Inner Mongolia August 2012 Room 801-802 Tower B Gemdale Plaza No. 91 Jianguo Road Chaoyang District Beijing 100022 China Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For 60 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The Economist Intelligence Unit delivers its information in four ways: through its digital portfolio, where the latest analysis is updated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York Economist Intelligence Unit Economist Intelligence Unit 26 Red Lion Square The Economist Group London 750 Third Avenue WC1R 4HQ 5th Floor United Kingdom New York, NY 10017, US Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000 Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500 Fax: (1.212) 586 0248 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Hong Kong Geneva Economist Intelligence Unit Economist Intelligence Unit 60/F, Central Plaza Boulevard des Tranchées 16 18 Harbour Road 1206 Geneva Wanchai Switzerland Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Tel: (41) 22 566 2470 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 Fax: (41) 22 346 93 47 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] This report can be accessed electronically as soon as it is published by visiting store.eiu.com or by contacting a local sales representative. The whole report may be viewed in PDF format, or can be navigated section-by-section by using the HTML links. -

Resource Curse” Based on the Panel Data in Coal Resource-Rich Districts of Inner Mongolia

E3S Web of Conferences 118, 01015 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/201911801015 ICAEER 2019 Study on “Resource Curse” Based on the Panel Data in Coal Resource-Rich Districts of Inner Mongolia Yao Hong1, Tian Meirong2*, Ma Jianjun 1, 2, She Xinlu3, and Gao Jixi4 1 Lang Fang Normal University, Lang fang 065000, China 2 Nanjing Institute of Environmental Sciences, Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China, Nanjing 210042, China 3 Renmin University of China, Beijing 100872, China 4 Ministry of Ecology and Environment Center for Satellite Application on Ecology and Environment, Beijing 100094, China Abstract. In order to analyse whether there is "Resource curse" in coal resource-rich district of Inner Mongolia such as Xilinguole, Hulunbeier, Tongliao, Chifeng, Erdos and Wuhai during "Golden ten years" (form 2000 to 2011) of coal, we developed the regression model based on the panel data of coal development intensity, manufacturing investment level, R&D and education investment level and foreign investment level, and test the "resource curse" effect in a holistic and regional way. The results showed that there exist "Resource curse" effect in Inner Mongolia along with economic development, and the effect gradually enhance. Meanwhile, the most serious "Resource curse" exist in Xilinguole, Hulunbeier, Erdos. The most important ways to weaken the “Resource curse” is industrial diversification and technological innovation. In addition, the basic way to solve or avoid "Resource curse" is strengthening the system construction, improving -

Inner Mongolia Sustainable Cross Border Development Investment Program (RRP PRC 51192) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT to the ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

Inner Mongolia Sustainable Cross Border Development Investment Program (RRP PRC 51192) SUPPLEMENTARY DOCUMENT TO THE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS 1. Introduction and background 1.1 PRC–Mongolia Trade and Cooperation 1. Since the establishment of trade relations between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Mongolia in 1951, the two countries signed a border trade treaty in 1962. The two countries have conducted in-depth cooperation in economic and trade aspects, and their scope has continued to expand. PRC has become Mongolia's largest trading partner. In 2018, the bilateral trade volume between PRC and Mongolia reached $8.54 billion, of which the PRC’s export volume was $1.99 billion and the import value was $6.54 billion. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR) has accounted for 70% of Mongolia’s import trade from PRC, and the IMAR’s import and export trade to Mongolia accounts for more than 40% of PRC-Mongolia trade. 2. According to the statistics of PRC–Mongolia economic and trade cooperation (Table 1), PRC continues to maintain Mongolia's largest trading partner, largest export market and largest import market in 2017. Mongolia's exports to PRC mainly include mineral products, animal fur raw materials and their finished products. Mongolia's imports from PRC mainly include gasoline, diesel, food, machinery and equipment, summarized is Table 1. Table 1: PRC–Mongolia Economic and Trade Cooperation Data for 2012-2017 Main Indicator 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 China export ($ billion) 2.450 2.216 1.572 0.988 1.248 China import ($ billion) 3.506 5.093 3.779 3.619 5.118 Source: China Customs Statistical Data. -

Analysis of Land Use Dynamics and Driving Forces in Xilin Gol

International Journal of Science Vol.8 No.7 2021 ISSN: 1813-4890 Analysis of Land Use Dynamics and Driving Forces in Xilin Gol League, Inner Mongolia Wu Ji Si Gu Leng1, Aruhan1,* 1School of Desert Control Science and Engineering, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot 010011, China. *Correspondence Author Abstract Based on the remote sensing data of Xilin Gol League in 1995, 2005, 2015 and 2020, with the support of ENVI5.3 and ArcGis10.6, this paper analyzes the dynamic evolution law of land use in Xilin Gol League by using land use transfer, land use dynamic attitude and driving force, and provides reference for land management and ecological protection in Xilin Gol League. The results showed that: (1) From 1995 to 2020, the area of Cropland, forest land, industrial and mining and water area all showed an increasing trend, while the area of grassland and unused land showed a decreasing trend (2) From 1995 to 2020, the dynamic attitude of single land use of Cropland, forest land, water area, industrial and mining in-creased, while grassland and unused land decreased. The dynamic attitude of comprehensive land use showed an overall downward trend. (3) The dynamic change of land use in Xilin Gol League from 1995 to 2020 is mainly due to the influence of population increase, rapid eco-nomic development and natural environment factors. Keywords Transfer Matrix; Land Use; Driving Force; Xilingol League. 1. Introduction Land use refers to the use status of land or the social and economic attributes of land [1], including the use mode of land biophysical characteristics and also the intention hidden under thecontrol of land biophysical characteristics.