Keeping Older Drivers Safe and Mobile a Survey of Older Drivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter August 2018

Newsletter August 2018 IN THIS ISSUE • AGM calling notice • A message from our Chairman, Graham Ranshaw • David McCarthy remembered • Chief Observer asks WHY? • Road-trains…….the future? • Your next car? The future of the car will be hybrid ! • IAM RoadSmart articles • Our recent IAM RoadSmart “GAM Scorecard” Newsletter of the Guildford & District Group of Advanced Motorists © GAM 2018 1 Registered Charity No. 1051069 AGM calling notice Guildford & District Group of Advanced Motorists AGM Notice NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN By order of the Group Committee that the 43rd Annual General Meeting of the Guildford & District Group of Advanced Motorists will Be held at Ripley Village Hall GU23 6AF on Saturday 29th SeptemBer 2018 at midday to enaBle the Trustees of the Group (Registered Charity No. 1051069) to present their Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31 March 2018 for approval by the Group Full Members and to conduct an election. All Group Full MemBers, Associates and Friends are invited to attend But only Group Full MemBers may vote. A MemBer entitled to vote at the General Meeting may appoint a proxy to vote in his stead. A proxy need not Be a Group Full MemBer. Nominations are invited from Group Full MemBers to stand for committee. The Nominee must Be willing to stand for the Committee and sign the Nomination. By signing the Nomination the Nominee is affirming his/her aBility and intention, if elected, to attend committee meetings regularly. NOTES: You may not stand for the Committee if the law deBars you from Being a Charity Trustee. Only Group Full MemBers may nominate Committee MemBers or Be nominated as Committee MemBers. -

IAM Roadsmart Group Affiliate Handbook V3.0 March 2019

IAM RoadSmart Group Affiliate Handbook V3.0 March 2019 Institute of Advanced Motorists IAM RoadSmart Group Handbook Version V3.0 Author/creator Amanda Smith Authoriser Patrick Doughty Owner/department Charity & Operations Document classification Unrestricted Document Status Approved History and Revisions Version Created by Document Revision History Date Published Classification V3.0 Amanda Smith Unrestricted March 2019 Authorisation Version Authorised by Department Date V3.0 Patrick Doughty Unrestricted March 2019 IAM RoadSmart 3 CONTENTS History and Revisions 3 Authorisation 3 IAM RoadSmart Introduction 8 Group Rules of Affiliation 8 IAM RoadSmart Charitable Objectives and Goals 9 Aims and Objectives of IAM RoadSmart 9 Strategic Goals of IAM RoadSmart 9 IAM RoadSmart Policy on Road Traffic Regulations 10 Statement From Standards 10 IAM RoadSmart Brand 11 Guidelines 11 Marketing Toolkit 12 Objectives of a Group 13 Introduction 14 Group Name “Known As” 14 Group Committee Composition 14 Group Membership Categories 15 Group Full Members 15 Group Honorary Members 15 Group Associate Members 15 Group Friends 16 Roles and Responsibilities of the Group Committee 16 Committee Meetings 17 Annual General Meetings and Extraordinary General Meetings 17 Finance 17 Expulsion of Group Member 18 Winding-up 18 Day-to-Day Leadership of the Group 19 Roles and Responsibilities – Group Officers 19 Group Officials – Succession Planning 21 Group Committee Members 22 IAM RoadSmart Group Communications 22 Charitable Status 23 Isle of Man (IoM) 24 Gift Aid 25 Gift -

Iam Lincolnshire Winter 2019

IAM LINCOLNSHIRE www.iamlincolnshire.com WINTER 2019 THE LATEST FROM IAM LINCOLNSHIRE We look forward to Page 10 shares our great range Page 5 of events which offer something Volunteer Bio: Geoff Coughlin for all. Why not add attending at seeing you in 2020! Page 6 least one of these to your New We’d like to wish all our readers Letter from Australia a Happy New Year, we hope you Year’s Resolutions! had a good festive period. Page 7 In this edition Letter from Australia cont. A new decade brings renewed enthusiasm as we look to the Page 2 Page 8 future. With over 200 full 2019 test passes Fordie’s World members and 70 members Page 3 Page 9 currently undertaking an Group News Know Your Stuff advanced course, we hope to Page 10 see as many of you as possible Page 4 Events Programme throughout the year. PCC Young Driver Project update Prepared for Winter? Smooth and slow, ready for snow! Contact us… something you’d like to share in the newsletter? By phone: By email: 0300 365 0152 [email protected] By post: IAM Lincolnshire, 33 Flaxley Road, LINCOLN, LN2 4GL Join us on @IAMLincolnshire IAM Lincoln - Issue 22 Winter 2019 Registered Charity Number: 1049400 1 IAM LINCOLNSHIRE www.iamlincolnshire.com WINTER 2019 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 53 ADVANCED DRIVERS WHO PASSED THEIR TESTS IN 2019! Associate Pass Date Observer Check Drive Observer Barrie Butler 20/12/2019 Tony Lofts John Edwards Bryan Mander 20/12/2019 F1RST David Hosegood Tony Winn 20/12/2019 Geoff Coughlin Mat Goddard Kevin Baker 15/12/2019 F1RST Simon Clayton Bob Bates Jenny -

About the IAM Roadsmart – Advanced Driver Course

Newsletter November 2017 Off-siding IN THIS ISSUE • A message from our Chairman, Graham Ranshaw. • New speeding penalties. • “Off-siding” and other IAM RoadSmart guidance. • John Holcroft reviews an IAM RoadSmart “Skills day” at Thruxton • More thoughts on vehicle technology; what about ‘Infotainment” systems? • GAM AGM highlights and finances. • Ripley Village Hall – fund raising news. Newsletter of the Guildford & District Group of Advanced Motorists © GAM 2017 1 Registered Charity No. 1051069 Chairman’s message Graham Ranshaw – November 2017. My wife and I were lucky enough to have a holiday in South Africa recently and we drove around the Western Cape from Cape Town to Port Elizabeth via Franshhoek, Hermanus and Knysna. Our preconceived concerns about security, road quality and driving standards were unfounded however. It is generally recommended not to drive after dark, which is a good idea given how remote some of the areas are. The networks are very well signed and almost perfectly surfaced – e.g. unlike Surrey...! The standard of driving was very good and remarkably relaxed – we encountered no frustrating lane blocking, speeding, tailgating or any of the vices that the UK specialises in! The two mountain passes that we navigated were exceptional – the best one was from Franschhoek (Wine region) to Hermanus (Whale watching) - up to around 3000 ft and reminiscent of a good Alpine pass. Lovely wide, quiet, open roads with excellent sight lines, very few Lycra clad cyclists, a fair few BMW GS1200s and everyone respectful of using the same space. Our car was a Toyota Fortuner a large 4x4 seven seater – more than enough room for 4 people and 2 weeks of luggage. -

Central Southern Advanced Motorists

CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS www.iamroadsmart.com/groups/centralsouthern NEWSLETTER SUMMER 2018 CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS PRESIDENT Dennis Clement CSAM COMMITTEE Chairman Tony Higgs 01243 699976 [email protected] Vice Chairman Tom Stringer 07786 266541 [email protected] Secretary Dave Stribling 07455 826862 [email protected] Treasurer Duncan Ford OBE 07920 534475 [email protected] Chief Observer Phil Coleman 01243 376569 [email protected] Membership Andy Wilson 01329 483661 [email protected] Social Media Tom Stringer [email protected] OTHER OFFICERS Associate Liaison Glenda Biggs 01489 808617 [email protected] Newsletter & Website Editor Tina Thurlow 01243 533092 [email protected] Registered address 65 Worcester Road, Chichester, PO19 5EB www.iam.org.uk/ Registered Charity No. 1079142 Summer 2018 ~ Page 2 CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS From the Editor As I sit at my desk - inside, but happy that the sun is shining outside - I can hear the birds discussing whether Summer really has arrived at last. Let's hope so: we've waited a long time this year. It's not, of course, only that good weather is nicer, but CSAM holds its events outside in the summer, so it really matters! I hope you'll enjoy this issue: it's full of interesting reports, articles, ideas, and the usual smattering of lighter material. Thanks, as always, to all the contributors. You'll see that Sheila Girling throws down the gauntlet over one problem that I think we all suffer from, so if you are a frustrated inventor who might have a solution I shall look forward to hearing from you! Have a good summer. -

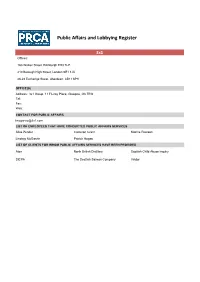

Public Affairs and Lobbying Register

Public Affairs and Lobbying Register 3x1 Offices: 16a Walker Street, Edinburgh EH3 7LP 210 Borough High Street, London SE1 1JX 26-28 Exchange Street, Aberdeen, AB11 6PH OFFICE(S) Address: 3x1 Group, 11 Fitzroy Place, Glasgow, G3 7RW Tel: Fax: Web: CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Ailsa Pender Cameron Grant Katrine Pearson Lindsay McGarvie Patrick Hogan LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED Atos North British Distillery Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry SICPA The Scottish Salmon Company Viridor Public Affairs and Lobbying Register Aiken PR OFFICE(S) Address: 418 Lisburn Road, Belfast, BT9 6GN Tel: 028 9066 3000 Fax: 028 9068 3030 Web: www.aikenpr.com CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Claire Aiken Donal O'Neill John McManus Lyn Sheridan Shane Finnegan LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED Diageo McDonald’s Public Affairs and Lobbying Register Airport Operators Associaon OFFICE(S) Address: Airport Operators Association, 3 Birdcage Walk, London, SW1H 9JJ Tel: 020 7799 3171 Fax: 020 7340 0999 Web: www.aoa.org.uk CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Ed Anderson Henk van Klaveren Jeff Bevan Karen Dee Michael Burrell - external public affairs Peter O'Broin advisor Roger Koukkoullis LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED N/A Public Affairs and -

Wessex Advanced Motorists

WESSEX ADVANCED MOTORISTS www.wessexam.uk Number 145 Winter 2017 WESSEX ADVANCED MOTORISTS e-NEWSLETTER Published Quarterly Editor: David Walton IAM Group No. 1005 Registered Charity No. 1062207 www.wessexam.uk Any comments or opinions expressed in this e-Newsletter are those of the contributors and not necessarily of the Institute of Advanced Motorists Ltd., Editor or Committee. Please send any items for consideration to be included in the next e-Newsletter to David Walton, our Editor (details on the back page). Items will be published ASAP. DATA PROTECTION ACT Members’ details, i.e. names, addresses and telephone numbers, are kept on computer to assist group administration. This information will not be passed outside the IAM. WAM may from time to time publish photographs taken at group events in this newsletter and on the website or display them at publicity events. If you do not wish to have your photo taken or published by WAM, please contact the Editor in writing (contact details on the back page). 35 With a Little Help From Our Friends 4 Chairman’s report from 2017 AGM 37 I never take drugs and drive – really? 10 The Committee 39 Advice about VAG group DSG gearboxes 11 Group Observers 40 Michael’s Drive for Improvement, Part 1 12 Calendar 42 Messages from Grateful Associates 13 President’s Ponderings 44 Emissions explained 16 Members’ Page 46 Patrick Hopkirk proves the equal of rally legend dad Paddy – 17 Events Corner and passes IAM RoadSmart advanced test again! 25 Member’s evening - raffle 48 Hitting the big 3-7 26 Dr. -

Competition for Btcc Weekend Tickets

COMPETITION FOR BTCC WEEKEND TICKETS IAM RoadSmart is offering one lucky winner the chance to WIN two adult BTCC Weekend Tickets for Saturday 28th and Sunday 29th August. More details on the event here IAM RoadSmart regularly partner with the racing circuit several times a year to host events for members and non-members. To be in with a chance of winning the tickets, all you need to do is send your name, address, email and contact number to [email protected]. The competition closes on Tuesday 17th August 2021 and the winner will be announced on Wednesday 18th August 2021. No purchase necessary and the winner will be selected at random. Full prize details can be found here. Tiff Needell BMW M4 Passenger Ride Experience Star of Top Gear and Fifth Gear, F1 Driver and Le Mans racer Tiff Needell, offers a unique high-speed passenger ride in the new BMW M4 at Thruxton – the fastest circuit in the UK. Hold on tight, this is a white-knuckle ride you'll never forget. Experience Tiff's legendary car control firsthand from the passenger seat of the brand new BMW M4, the perfect machine for Tiff to demonstrate why he made it all the way to Formula 1 and the Le Mans 24 hours. To complete this unique experience, you will be filmed from inside the car in full 360 view, 4k resolution allowing you to watch the footage back on all your devices and look around in and outside the car, including Tiff's commentary of your laps. -

CSAM Newsletter

CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS www.iamroadsmart.com/groups/centralsouthern NEWSLETTER SUMMER 2017 CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS CSAM COMMITTEE Chairman Dennis Clement 01243 553097 [email protected] Vice Chairman Tony Higgs 01243 699976 [email protected] Secretary Dave Stribling 07455 826862 [email protected] Treasurer Duncan Ford OBE 07920 534475 [email protected] Chief Observer Gary Smith 01243 828225 [email protected] Membership Andy Wilson 01329 483661 [email protected] Social Media Tom Stringer [email protected] OTHER CONTACTS Associate Liaison Glenda Biggs 01243 263537 [email protected] Newsletter & Website Editor Tina Thurlow 01243 533092 [email protected] Registered address 65 Worcester Road, Chichester, PO19 5EB www.iam.org.uk/ Registered Charity No. 1079142 SUMMER 2017 ~ Page 2 CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS From the Editor I hope you'll enjoy the Summer Newsletter. As usual, I'm immensely grateful to all the contributors, whether of text, photographs or ideas on the content and/or presentation of the Newsletter: all are very welcome. Regarding articles in this issue, particular mention must be made of Dave Harris, whose regular "Tips" are sadly coming to an end. I am very much in his debt for his great support for our Newsletter over the years, and I'm happy to say he has said he may still feel moved to write something for us from time to time: very good news. Thank you, Dave! Have you ever wondered how to ride a motorcycle? All CSAM Members will have received from IAM RoadSmart, via Andy Wilson, an invitation to have a "taster session" during BikeFest South being held at the Goodwood Circuit on 11th June. -

Cranfield University Nur Khairiel Anuar the Impact Of

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY NUR KHAIRIEL ANUAR THE IMPACT OF AIRPORT ROAD WAYFINDING DESIGN ON SENIOR DRIVER BEHAVIOUR CENTRE FOR AIR TRANSPORT MANAGEMENT SCHOOL OF AEROSPACE, TRANSPORT AND MANUFACTURING PhD in Transport Systems PhD Academic Year: 2015 - 2016 Supervisors: Dr Romano Pagliari / Mr Richard Moxon August 2016 CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY CENTRE FOR AIR TRANSPORT MANAGEMENT SCHOOL OF AEROSPACE, TRANSPORT AND MANUFACTURING PhD in Transport Systems PhD Academic Year 2015 - 2016 NUR KHAIRIEL ANUAR The Impact of Airport Road Wayfinding Design on Senior Driver Behaviour Supervisors: Dr Romano Pagliari / Mr Richard Moxon August 2016 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Transport Systems © Cranfield University 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner. ABSTRACT Airport road access wayfinding refers to a process in which a driver makes a decision to navigate using information support systems in order to arrive to airport successfully. The purpose of this research is to evaluate senior drivers’ behaviour of alternative airport road access designs. In order to evaluate the impact of wayfinding, the combination of simulated driving and completion of a questionnaire were performed. Quantitative data was acquired to give significant results justifying the research outcomes and allow non-biased interpretation of the research results. It represents the process within the development of the methodology and the concept of airport road access design and driving behaviour. Wayfinding complexity varied due to differing levels of road-side furniture. The simulated driving parameters measured were driving mistakes and performances of senior drivers. -

RAC Report on Motoring 2018 the Frustrated Motorist

RAC Report on Motoring 2018 The frustrated motorist CELEBRATING OF THE REPORT ON MOTORING Mark Souster, RAC Patrol #OrangeHero of the Year 2018 CELEBRATING OF THE REPORT ON MOTORING RAC Report on Motoring Contents Foreword 4 5 Vehicle use and choice of next car 66 Executive summary 6 5.1 Car use rising, not falling 70 5.2 Choice of next car: 1 What’s on motorists’ minds? 10 a confusing picture 74 1.1 The state of our roads 16 1.2 The behaviour of other drivers 20 6 Calls to action 80 1.3 The cost of motoring 22 7 Our campaigns 84 2 The state of our roads 26 8 Our successes 86 2.1 The condition of local roads 32 2.2 The strategic road network 38 9 Who is the motorist? 88 2.3 Congestion and journey 10 Appendix 89 times on all roads 40 10.1 Research methodology 89 3 The dangers on our roads 42 10.2 Statistical reliability 89 3.1 Mobile phone use: concern versus compliance 46 11 30 years of the Report on Motoring 90 3.2 Drink- and drug-driving 49 3.3 Speed limits and speed 12 Always innovating to awareness courses 50 help our members 92 3.4 Traffic law enforcement and the Highway Code 53 13 Company overview/Contacts 94 4 Air quality and the environment 56 4.1 Local air quality concerns 58 4.2 Policies to tackle pollution 62 3 RAC Report on Motoring 2018 Foreword Foreword More details at Wing Commander Andy Green OBE bloodhoundssc.com I am delighted to introduce the 2018 RAC Report As in previous Reports, road safety The range of pure electric vehicles is an important theme. -

Central Southern Advanced Motorists

CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS www.iamroadsmart.com/groups/centralsouthern NEWSLETTER SUMMER 2019 CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS PRESIDENT Dennis Clement CSAM COMMITTEE Chairman Tony Higgs 01243 699976 [email protected] Vice Chairman Tom Stringer 07786 266541 [email protected] Secretary Dave Stribling 07455 826862 [email protected] Treasurer Duncan Ford OBE 07920 534475 [email protected] Chief Observer Phil Coleman 01243 376569 [email protected] Membership Matthew Pitt 02392 595817 [email protected] Social Media Tom Stringer 07786 266541 [email protected] OTHER OFFICERS Associate Liaison Glenda Biggs 01489 808617 [email protected] Newsletter & Website Editor Tina Thurlow 01243 533092 [email protected] Registered address 65 Worcester Road, Chichester, PO19 5EB www.iam.org.uk/ Registered Charity No. 1079142 Summer 2019 ~ Page 2 CENTRAL SOUTHERN ADVANCED MOTORISTS From the Editor I am delighted that this issue of the Newsletter is absolutely packed with interesting goodies for CSAM Members - and others who may light upon it via our website. Along with the officers' reports, 'From Reflector' and other interesting and/or amusing pieces, this edition contains several contributions from some who have not appeared before within these 'pages'. I am, as always, grateful to you all for sharing your thoughts - in many cases I would go so far as to say wisdom - with us; apart from anything else, it makes putting the Newsletter together a thoroughly enjoyable task for 'yours truly'. I hope you will all have a good and safe summer, whether on the roads, in the air or just enjoying getting away from it all in your back garden.