Renaissance to the Early Modern Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

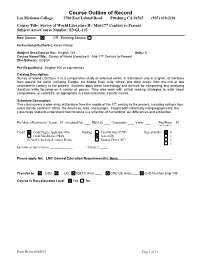

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Robert Fredona Working Paper 18-021 Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Robert Fredona Harvard Business School Working Paper 18-021 Copyright © 2017 by Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona ABSTRACT: N.S.B. Gras, the father of Business History in the United States, argued that the era of mercantile capitalism was defined by the figure of the “sedentary merchant,” who managed his business from home, using correspondence and intermediaries, in contrast to the earlier “traveling merchant,” who accompanied his own goods to trade fairs. Taking this concept as its point of departure, this essay focuses on the predominantly Italian merchants who controlled the long‐distance East‐West trade of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Until the opening of the Atlantic trade, the Mediterranean was Europe’s most important commercial zone and its trade enriched European civilization and its merchants developed the most important premodern mercantile innovations, from maritime insurance contracts and partnership agreements to the bill of exchange and double‐entry bookkeeping. Emerging from literate and numerate cultures, these merchants left behind an abundance of records that allows us to understand how their companies, especially the largest of them, were organized and managed. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Cross Cultural Interaction: Early Modern Period

Cross Cultural Interaction: Early Modern Period Summary. A new era of world history, the early modern period, was present between 1450 and 1750. The balance of power between world civilizations shifted as the West became the most dynamic force. Other rising power centers included the empires of the Ottomans, Mughals, and Ming, and Russia. Contacts among civilizations, especially in commerce, increased. New weaponry helped to form new or revamped gunpowder empires. On the Eve of the Early Modern Period: The World around 1400. New or expanded civilization areas, in contact with leading centers, had developed during the postclassical period. A monarchy formed in Russia. Although western Europeans did not achieve political unity, they built regional states, expanded commercial and urban life, and established elaborate artistical and philosophical culture. In sub‐Saharan Africa loosely organized areas shared vitality with new regional states; trade and artistic expression grew. Chinese‐influenced regions, like Japan, built more elaborate societies. Some cultures ‐ African, Polynesian, American ‐ continued to develop in isolation. In Asia, Africa, and Europe between the 13th and 15th centuries the key developments were the decline of Islamic dynamism and the Mongol conquests. After 1400 a new Chinese empire emerged and the Ottoman Empire reformed the Islamic world. The Rise of the West. The West, initially led by Spain and Portugal, won domination of international trade routes and established settlements in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. The West changed rapidly internally because of agricultural, commercial, political, and religious developments. A scientific revolution reshaped Western culture. The World Economy and Global Contacts. The world network expanded well beyond previous linkages. -

Early Modern Japan

December 1995 Early Modern Japan KarenWigen) Duke University The aims of this paperare threefold: (I) to considerwhat Westernhistorians mean when they speakof Early Modern Japan,(2) to proposethat we reconceivethis period from the perspectiveof world networks history, and (3) to lay out someof the advantagesI believe this offers for thinking aboutSengoku and Tokugawasociety. The idea that Japan had an early modern period is gradually becoming common in every sector of our field, from institutional to intellectual history. Yet what that means has rarely been discussed until now, even in the minimal sense of determining its temporal boundaries: I want to thank David Howell and James Ketelaar for raising the issue in this forum, prompting what I hope will become an ongoing conversation about our periodization practices. To my knowledge, the sole attempt in English to trace the intellectual genealogy of this concept is John Hall's introduction to the fourth volume of the Cambridge History of Japan-a volume that he chose to title Early Modern Japan. Hall dates this expression to the 1960s, when "the main concern of Western scholars of the Edo period was directed toward explaining Japan's rapid modernization." Its ascendancy was heralded by the 1968 publication of Studies in the Institutional History of Early Modern Japan, which Hall co-edited with Marius Jansen. "By declaring that the Tokugawa period should be called Japan's 'early modern' age," he reflects, "this volume challenged the common practice of assuming that Japan during the Edo period was still fundamentally feudal.") Although Hall sees the modernization paradigm as having been superseded in later decades, he nonetheless reads the continuing popularity of the early modern designation as a sign that most Western historians today see the Edo era as "more modern than feudal.',4 This notion is reiterated in even more pointed terms by Wakita Osamu in the same volume. -

A Short History of the British Factory House in Lisbon1

A Short History of the British Factory House in Lisbon1 Reprinted from the 10th Annual Report of the British Historical Association - 1946 Kindly transcribed from the original Report by the Society’s Librarian, Dani Monteiro, maintaining the original grammar of the article. By Sir Godfrey Fisher, K. C. M. G It is a curious and regrettable fact that so little information is available about those trading communities, or factories, which developed independently of control or assistance from their home country and yet played such an important part not only in our commercial expansion but in our naval predominance at the time when the distant Mediterranean suddenly became the great strategic battle-ground - the “Keyboard of Europe”. Thanks to the ability and industry of Mr. A. R. Walford we now have a picture of the great British Factory at the vital port of Lisbon during the latter part of its history.2 Of the earlier part, which is “shrouded in obscurity” I would venture to place on record a few details which have attracted my attention while trying to find out something about the history of our early consuls who were originally chosen, if not actually appointed, by them to be their official spokesmen and chief executives. An interesting but perhaps characteristic feature of these establishments, or associations, for that is probably a more accurate description, is that they were not legal entities at all and their correct official designation seems to have been the “Consul and the Merchants” or the “Consul and the Factors”. The consul himself on the other hand had an unquestionable legal status, decided more than once in the Spanish courts in very early times, and was established by, or under authority from, royal patents. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

Chapter I the Portuguese Empire

Decay or defeat ? : an inquiry into the Portuguese decline in Asia 1580-1645 Veen, Ernst van Citation Veen, E. van. (2000, December 6). Decay or defeat ? : an inquiry into the Portuguese decline in Asia 1580-1645. Research School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies (CNWS), Leiden University. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15783 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15783 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER I THE PORTUGUESE EMPIRE The boundaries Until well into the seventeenth century, as far as the Iberians were concerned, the way the world was divided and the role they were to play therein as champions of the church was clear-cut and straightforward. Already in the fifteenth century the rights of the Portuguese monarchs on the portus, insulas, terras et maria still to be conquered had been confirmed by Papal edicts. They bestowed the privilege to intrude into the countries of the Saracenes and heathens, to take them prisoner, take all their possessions and reduce them to eternal slavery. Derived from this right of conquest were the rights of legislation, jurisdiction and tribute and the monopolies of navigation, trade and fishing. Besides, the kings were allowed to build churches, cloisters and other holy places and to send clergy and other volunteers, to spread the true religion, to receive confessions and to give absolutions. Excommunication or interdiction were the penalties for Christians who violated these royal monopolies.1 As the Castilians were just as keen on the collection of slaves and gold and the overseas expansion of the mission, a clash of interests was inevitable.2 In 1479, the Castilians used the opportunity of king Afonso V's defeat, after he attempted to acquire the Castilian throne, to establish their rights on the Canary islands. -

Ch 16: Religion and Science 1450–1750

Ch 16: Religion and Science 1450–1750 CHAPTER OVERVIEW CHAPTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES • To explore the early modern roots of modern tension between religion and science • To examine the Reformation movements in Europe and their significance • To investigate the global spread of Christianity and the extent to which it syncretized with native traditions • To expand the discussion of religious change to include religious movements in China, India, and the Islamic world • To explore the reasons behind the Scientific Revolution in Europe, and why that movement was limited in other parts of the world • To explore the implications of the Scientific Revolution for world societies CHAPTER OUTLINE I.Opening Vignette A.The current evolution vs. “intelligent design” debate has its roots in the early modern period. 1.Christianity achieved a global presence for the first time 2.the Scientific Revolution fostered a different approach to the world 3.there is continuing tension between religion and science in the Western world B.The early modern period was a time of cultural transformation. 1.both Christianity and scientific thought connected distant peoples 2.Scientific Revolution also caused a new cultural encounter, between science and religion 3.science became part of the definition of global modernity C.Europeans were central players, but they did not act alone. II.The Globalization of Christianity A.In 1500, Christianity was mostly limited to Europe. 1.small communities in Egypt, Ethiopia, southern India, and Central Asia 2.serious divisions within -

Lessons from York Factory, Hudson Bay

Trade, Consumption and the Native Economy: Lessons from York Factory, Hudson Bay October 2000 Ann M. Carlos is Professor, Department of Economics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0256, e-mail: [email protected]. Frank D. Lewis, is Professor, Department of Economics, Queen's University, Kingston, ON K7L 3N6, e-mail: [email protected]. Versions of this paper were presented at the Economic History Association Meetings, the Canadian Economic History Meetings (Kananaskis), and to workshops at the University of British Columbia, University of Colorado, University of Laval, and Queen's University. The authors thank the participants for their many helpful comments. Trade, Consumption and the Native Economy: Lessons from York Factory, Hudson Bay Like European and colonial consumers, eighteenth-century Native Americans were purchasing a greatly expanded variety of goods. Here the focus is on those Indians who traded furs, mainly beaver pelts, to the Hudson's Bay Company at its York Factory post. From 1716-1770, a period when fur prices rose, there was a shift in Indian expenditures from producer and household goods to tobacco, alcohol and other luxuries. We show, in the context of a model of consumer behavior, that the evidence on consumption patterns suggests strongly that Indians were increasing their purchases of European goods in response to the higher fur prices, and perhaps more importantly were increasing their effort in the fur trade. These findings are contrary to much that has been written about Indians as producers and consumers. Eighteenth-century families from the Friesenland to the Tidewater of the Chesapeake were accumulating goods.