Fusarium Solani Using a Novel Monoclonal Antibody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. In the book, we use the terms ‘fungal infections’ and ‘mycoses’ (or singular fungal infection and mycosis) interchangeably, mostly following the usage of our historical actors in time and place. 2. The term ‘ringworm’ is very old and came from the circular patches of peeled, inflamed skin that characterised the infection. In medicine at least, no one understood it to be associated with worms of any description. 3. Porter, R., ‘The patient’s view: Doing medical history from below’, Theory and Society, 1985, 14: 175–198; Condrau, F., ‘The patient’s view meets the clinical gaze’, Social History of Medicine, 2007, 20: 525–540. 4. Burnham, J. C., ‘American medicine’s golden age: What happened to it?’, Sci- ence, 1982, 215: 1474–1479; Brandt, A. M. and Gardner, M., ‘The golden age of medicine’, in Cooter, R. and Pickstone, J. V., eds, Medicine in the Twentieth Century, Amsterdam, Harwood, 2000, 21–38. 5. The Oxford English Dictionary states that the first use of ‘side-effect’ was in 1939, in H. N. G. Wright and M. L. Montag’s textbook: Materia Med Pharma- col & Therapeutics, 112, when it referred to ‘The effects which are not desired in any particular case are referred to as “side effects” or “side actions” and, in some instances, these may be so powerful as to limit seriously the therapeutic usefulness of the drug.’ 6. Illich, I., Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health, London, Calder & Boyars, 1975. 7. Beck, U., Risk Society: Towards a New Society, New Delhi, Sage, 1992, 56 and 63; Greene, J., Prescribing by Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Dis- ease, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007; Timmermann, C., ‘To treat or not to treat: Drug research and the changing nature of essential hypertension’, Schlich, T. -

Fusarium-Produced Mycotoxins in Plant-Pathogen Interactions

toxins Review Fusarium-Produced Mycotoxins in Plant-Pathogen Interactions Lakshmipriya Perincherry , Justyna Lalak-Ka ´nczugowska and Łukasz St˛epie´n* Plant-Pathogen Interaction Team, Department of Pathogen Genetics and Plant Resistance, Institute of Plant Genetics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Strzeszy´nska34, 60-479 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] (L.P.); [email protected] (J.L.-K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019; Published: 14 November 2019 Abstract: Pathogens belonging to the Fusarium genus are causal agents of the most significant crop diseases worldwide. Virtually all Fusarium species synthesize toxic secondary metabolites, known as mycotoxins; however, the roles of mycotoxins are not yet fully understood. To understand how a fungal partner alters its lifestyle to assimilate with the plant host remains a challenge. The review presented the mechanisms of mycotoxin biosynthesis in the Fusarium genus under various environmental conditions, such as pH, temperature, moisture content, and nitrogen source. It also concentrated on plant metabolic pathways and cytogenetic changes that are influenced as a consequence of mycotoxin confrontations. Moreover, we looked through special secondary metabolite production and mycotoxins specific for some significant fungal pathogens-plant host models. Plant strategies of avoiding the Fusarium mycotoxins were also discussed. Finally, we outlined the studies on the potential of plant secondary metabolites in defense reaction to Fusarium infection. Keywords: fungal pathogens; Fusarium; pathogenicity; secondary metabolites Key Contribution: The review summarized the knowledge and recent reports on the involvement of Fusarium mycotoxins in plant infection processes, as well as the consequences for plant metabolism and physiological changes related to the pathogenesis. -

Small Rnas from Plants, Bacteria and Fungi Within the Order Hypocreales Are Ubiquitous in Human Plasma

Small RNAs from plants, bacteria and fungi within the order Hypocreales are ubiquitous in human plasma Beatty, M., Guduric-Fuchs, J., Brown, E., Bridgett, S., Chakravarthy, U., Hogg, R. E., & Simpson, D. A. (2014). Small RNAs from plants, bacteria and fungi within the order Hypocreales are ubiquitous in human plasma. BMC Genomics, 15, [933]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-933 Published in: BMC Genomics Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Beatty et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. -

Characteristics and Host Range of a Novel Fusarium Species Causing

CHARACTERISTICS AND HOST RANGE OF A NOVEL FUSARIUM SPECIES CAUSING YELLOWING DECLINE OF SUGARBEET A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Johanna Patricia Villamizar-Ruiz In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Plant Pathology November 2013 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title CHARACTERISTICS AND HOST RANGE OF A NOVEL FUSARIUM SPECIES CAUSING YELLOWING DECLINE OF SUGARBEET By JOHANNA PATRICIA VILLAMIZAR-RUIZ The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Gary Secor Chair Dr. Mohamed Khan Dr. Luis del Río Mendoza Dr. Marisol Berti Approved: Nov 14 / 2013 Dr. Jack Rasmussen Date Department Chair ABSTRACT In 2008, a novel and distinct Fusarium species was reported in west central Minnesota causing early-season yellowing and severe decline of sugarbeet. This study was conducted to (i) establish optimum conditions for fungal growth and (ii) determine the host range of the novel Fusarium . The optimum temperature for fungal growth is 24°C and root injury is not needed to penetrate, infect, and cause disease of sugarbeet plants. Of the fifteen common crops and weeds tested for susceptibility to the new Fusarium sp. in field and greenhouse trials, disease symptoms were only observed in sugarbeet. Host range plants were tested for the presence of latent infection by root isolations and PCR. The pathogen was only present in canola and sugarbeet. -

Bionectria Pseudochroleuca, a New Host Record on Prunus Sp. in Northern Thailand

Studies in Fungi 5(1): 358–367 (2020) www.studiesinfungi.org ISSN 2465-4973 Article Doi 10.5943/sif/5/1/17 Bionectria pseudochroleuca, a new host record on Prunus sp. in northern Thailand Huanraluek N1, Jayawardena RS1,2, Aluthmuhandiram JVS 1, 2,3, Chethana KWT1,2 and Hyde KD1,2,4* 1Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 2School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 3Institute of Plant and Environment Protection, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, People’s Republic of China 4Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Science, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China Huanraluek N, Jayawardena RS, Aluthmuhandiram JVS, Chethana KWT, Hyde KD 2020 – Bionectria pseudochroleuca, a new host record on Prunus sp. in northern Thailand. Studies in Fungi 5(1), 358–367, Doi 10.5943/sif/5/1/17 Abstract This study presents the first report of Bionectria pseudochroleuca (Bionectriaceae) on Prunus sp. (Rosaceae) from northern Thailand, based on both morphological characteristics and multilocus phylogenetic analyses of internal transcribe spacer (ITS) and Beta-tubulin (TUB2). Key words – Bionectriaceae – Clonostachys – Hypocreales – Nectria – Prunus spp. – Sakura Introduction Bionectriaceae are commonly found in soil, on woody substrates and on other fungi (Rossman et al. 1999, Schroers 2001). Bionectria is a member of Bionectriaceae (Rossman et al. 2013, Maharachchikumbura et al. 2015, 2016) and is distinct from other genera in the family as it has characteristic ascospores and ascus morphology, but none of these are consistently found in all Bionectria species (Schroers 2001). Some species of this genus such as B. -

Is There Scope for a Novel Mycelium Category of Proteins Alongside Animals and Plants?

foods Communication Is There Scope for a Novel Mycelium Category of Proteins alongside Animals and Plants? Emma J. Derbyshire Nutritional Insight, Surrey KT17 2AA, UK; [email protected] Received: 3 August 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: In the 21st century, we face a troubling trilemma of expanding populations, planetary and public wellbeing. Given this, shifts from animal to plant food protein are gaining momentum and are an important part of reducing carbon emissions and consumptive water use. However, as this fast-pace of change sets in and begins to firmly embed itself within food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) and food policies we must raise an important question—is now an opportunistic time to include other novel, nutritious and sustainable proteins within FBGD? The current paper describes how food proteins are typically categorised within FBDG and discusses how these could further evolve. Presently, food proteins tend to fall under the umbrella of being ‘animal-derived’ or ‘plant-based’ whilst other valuable proteins i.e., fungal-derived appear to be comparatively overlooked. A PubMed search of systematic reviews and meta-analytical studies published over the last 5 years shows an established body of evidence for animal-derived proteins (although some findings were less favourable), plant-based proteins and an expanding body of science for mycelium/fungal-derived proteins. Given this, along with elevated demands for alternative proteins there appears to be scope to introduce a ‘third’ protein category when compiling FBDG. This could fall under the potential heading of ‘fungal’ protein, with scope to include mycelium such as mycoprotein within this, for which the evidence-base is accruing. -

Chrysanthemum and Marigold

Research Article THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH (TIJOBR) ISSN Online: 2618-1444 Vol. 3(3) July-Sep. 2020., 01-18; 2020 http://www.rndjournals.com Polyphasic Taxonomy of Fusarium causing wilt in cut flower crops (Chrysanthemum and Marigold) and its chemical management Umar Muaz1*, Arooba Nawaz2, Akasha Mansoor2, Amar Ahmad Khan1, Zulnoon Haider1, Kamran Ahmad2 1Department of Plant Pathology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan 2Department of Botany, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan. *Corresponding author email: [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) and Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum L.) are important cut flower crops which are facing threat by wilting disease in Pakistan. Survey of important ornamental plant local nurseries, public parks and gardens of districts of Punjab Faisalabad, Lahore, Kasur, Vehari, and Islamabad were done. Samples of soil, root, shoot and leave from healthy as well as wilted portion of both crops were collected. Isolation was done to find the Fusarium species associated with diseased samples. Fusarium spp. was characterized using morphological characters. Cultural characters of Fusarium spp. on potato dextrose agar medium (color, texture and growth pattern) were studied. Microscopic characters of Fusarium equiseti on different magnification (Mycelial structure, conidia shape and size) were observed. Molecular characterization of morphologically identified Fusarium equiseti was done and submitted to Gene bank with accession no. MN135748 and MN135746. Characterized Fusarium equiseti was preserved on agar slants and dry filters papers in FMB-CC-UAF with Accession No. FMB0151, FMB0152. Pathogenicity was confirmed following by Koch’s postulates. Chemical control is one of the best management strategies that is used commonly to control the diseases. -

Download Chapter

4 State of the World’s Fungi State of the World’s Fungi 2018 4. Useful fungi Thomas Prescotta, Joanne Wongb, Barry Panaretouc, Eric Boad, Angela Bonda, Shaheenara Chowdhurya, Lee Daviesa, Lars Østergaarde a Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK; b Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Switzerland; c King’s College London, UK; d University of Aberdeen, UK; e Novozymes A/S, Denmark 24 Positive interactions and insights USEFUL FUNGI the global market for edible mushrooms is estimated to be worth US$42 billion Per year What makes a species of fungus economically valuable? What daily products utilise fungi and what are the useful fungi of the future for food, medicines and fungal enzymes? stateoftheworldsfungi.org/2018/useful-fungi.html Useful fungi 25 26 Positive interactions and insights (Amanita spp.) and boletes (Boletus spp.)[2]. Most wild- FUNGI ARE A SOURCE OF NUTRITIOUS collected species cannot be cultivated because of complex FOOD, LIFESAVING MEDICINES AND nutritional dependencies (they depend on living plants to grow), whereas cultivated species have been selected to ENZYMES FOR BIOTECHNOLOGY. feed on dead organic matter, which makes them easier to grow in large quantities[2,3]. The rise of the suite of cultivated Most people would be able to name a few species of edible mushrooms seen on supermarket shelves today, including mushrooms but how many are aware of the full diversity of button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus), began relatively edible species in nature, still less the enormous contribution recently in the 1960s[3]. The majority of these cultivated fungi have made to pharmaceuticals and biotechnology? mushrooms (85%) come from just five genera: Lentinula, In fact, the co-opting of fungi for the production of wine and Pleurotus, Auricularia, Agaricus and Flammulina[4] (see leavened bread possibly marks the point where humans Figure 2). -

Anti Oxidative and Anti Tumour Activity of Biomass Extract of Mycoprotein Fusarium Venenatum

Vol. 7(17), pp. 1697-1702, 23 April, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/AJMR12.1065 ISSN 1996-0808 ©2013 Academic Journals African Journal of Microbiology Research http://www.academicjournals.org/AJMR Full Length Research Paper Anti oxidative and anti tumour activity of biomass extract of mycoprotein Fusarium venenatum Prakash P and S. Karthick Raja Namasivayam* Department of Biotechnology, Sathyabama University, Chennai – 119, Tamil Nadu, India. Accepted 25 March, 2013 Fusarium venenatum has been utilized as a mycoprotein source for human consumption in many countries for over a decade because of the rich source of high quality protein including essential amino acids and less fat. In the present study, anti oxidative and anticancer properties of biomass extract of Fusarium venenatum was studied. Biomass was obtained from Fusarium venenatum grown in Vogel’s minerals medium and the biomass thus obtained was purified, extracted with distilled water and ethanol. The water and ethanol extracts thus prepared were evaluated for anti oxidative activity with DPPH radical scavenging activity whereas the antitumour activity was studied with Hep 2 cell line adopting MTT assay. Cytotoxic effect of both the extracts on vero cell line and human peripheral blood cells was also studied. Maximum free radical scavenging activity was recorded in 1000 μg/ml concentration of ethanol extract. The anti tumor activity against HEP2 cell lines by MTT assay reveals 1000 μg/ml concentration inhibited maximum viability followed by 800 μg/ml. In the case of vero cell lines viability was not affected at all tested concentrations The effect of extracts was studied over the human peripheral blood RBC in which the lysis, reduction and changes in morphology of blood cells was not recorded in any concentration. -

Development of Fungal Leather-Like Material from Bread Waste

Development of Fungal Leather-like Material from Bread Waste Master Programme in Resource Recovery Industrial Biotechnology Egodagedara Ralalage Kanishka Bandara Wijayarathna Final Submission (2021.06.10) MAIN INFORMATION Programme: MSc degree in Resource Recovery in major of Industrial Biotechnology Swedish title: Utveckling av svampläderliknande material från bröd svinn English title: Development of fungal leather-like material from bread waste Year of publication: 2021 Authors: Egodagerada Ralalage Kanishka Bandara Wijayarathna Supervisor: Main-supervisor - Akram Zamani, Co-supervisor - Amir Mahboubi Soufiani. Examiner: Dan Åkesson Keywords: Leather, Fungal leather, Leather-like material, Food waste, Bread waste, Fungal material, Sustainable material, Filamentous fungi i ABSTRACT Food waste and fashion pollution are two of the significant global environmental issues throughout the recent past. In this research, it was investigated the feasibility of making a leather-like material from bread waste using biotechnology as the bridging mechanism. The waste bread collected from the supermarkets were used as the substrate to grow filamentous fungi species Rhizopus Delemar and Fusarium Venenatum. Tanning of fungal protein fibres was successfully performed using vegetable tanning, confirmed using FTIR and SEM images. Furthermore, glycerol and a biobased binder treatment was performed for the wet-laid fungal microfibre sheets produced. Overall, three potential materials were able to produce with tensile strengths ranging from 7.74 ± 0.55 MPa to 6.92 ± 0.51 MPa and the elongation% from 16.81 ± 1.61 to 4.82 ± 0.36. The binder treatment enhanced the hydrophobicity even after the glycerol treatment, an added functional advantage for retaining flexibility even after contact with moisture. The fungal functional material produced with bread waste can be tailored successfully into leather substitutes using an environmentally benign procedure. -

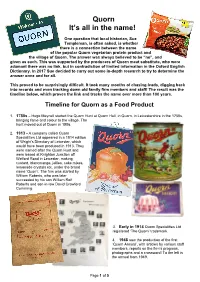

Quorn It's All in the Name!

Quorn It’s all in the name! One question that local historian, Sue Templeman, is often asked, is whether there is a connection between the name of the popular Quorn vegetarian protein product and the village of Quorn. The answer was always believed to be “no”, and given as such. This was supported by the producers of Quorn meat substitute, who were adamant there was no link, but in contradiction of limited information in the Oxford English Dictionary. In 2017 Sue decided to carry out some in-depth research to try to determine the answer once and for all. This proved to be surprisingly difficult. It took many months of chasing leads, digging back into records and even tracking down old family firm members and staff! The result was the timeline below, which proves the link and tracks the name over more than 100 years. Timeline for Quorn as a Food Product 1. 1750s – Hugo Meynell started the Quorn Hunt at Quorn Hall, in Quorn, in Leicestershire in the 1750s, bringing fame and colour to the village. The hunt moved out of Quorn in 1906. 2. 1913 - A company called Quorn Specialities Ltd appeared in a 1914 edition of Wright’s Directory of Leicester, which would have been produced in 1913. They were named after the Quorn Hunt and were based at Knighton Junction off Welford Road in Leicester, making custard, blancmange, jellies, cake mixes, lemonade crystals etc. under the brand name ‘Quorn’. The firm was started by William Roberts, who was later succeeded by his son William Rolf Roberts and son-in-law David Crawford Cumming. -

Small Rnas from Plants, Bacteria and Fungi Within the Order Hypocreales Are Ubiquitous in Human Plasma

Small RNAs from plants, bacteria and fungi within the order Hypocreales are ubiquitous in human plasma Beatty, M., Guduric-Fuchs, J., Brown, E., Bridgett, S., Chakravarthy, U., Hogg, R. E., & Simpson, D. A. (2014). Small RNAs from plants, bacteria and fungi within the order Hypocreales are ubiquitous in human plasma. BMC Genomics, 15, [933]. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-933 Published in: BMC Genomics Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Beatty et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws.